MOJ

eISSN: 2381-182X

Review Article Volume 6 Issue 2

1Islamic Food and Nutrition Council of America, Pakistan

2Department of Food Engineering, Istanbul Sabahattin Zaim University, Pakistan

Correspondence: Syed Fazal Ur Raheem, Shariah Advisor, Islamic Food and Nutrition Council of America, (Pakistan) Office, 144-A, Peoples Colony No: 2, Faisalabad, Pakistan

Received: February 06, 2018 | Published: March 13, 2018

Citation: Raheem SFU, Demirci MN. Assuring Tayyib from a food safety perspective in Halal food sector: a conceptual framework. MOJ Food Process Technol. 2018;6(2):170–179. DOI: 10.15406/mojfpt.2018.06.00161

This paper puts forth how food safety and hygienic practices are a part of the Halal concept and should thus be adapted by the Halal food sector to achieve Halal and Tayyib assurance. It further puts forth the concept of Halal prerequisites, which were established through identifying food safety and hygiene requirements in Islamic Jurisprudence. To move toward more efficient Halal and Tayyib practices these should be demanded, implemented, maintained and controlled by the whole Halal food sector, instead of just relying on the existence of food safety certification. A conceptual framework was constructed depicting the Halal sector’s possible passive and potential active Halal and Tayyib food safety control practices. It will enable the sector to gain insight to issues in Halal certification, food safety position within it and reach an understanding of improvement measures. The paper also suggests recognising and incorporating the Halal prerequisites and other sector specific requirements as Halal Control Points (HCPs) to the Halal HACCP system.

Keywords: tayyib, food safety, hygiene, halal, haraam, islamic jurisprudence, haccp, prps

From raw ingredients to final products food safety assurance covers the whole supply chain. Despite that in 2010 approximately 600 million foodborne disease cases were reported globally, with an estimated 400 thousand deaths.1 Food safety assurance is thus complicated and research is constantly conducted with an aim to improve existing food safety measures, find effective approaches and identify food sector’s needs.2‒4 This in turn enables to analyse and understand its problems, issues and complexities and draw parallels with Halal assurance.

For Muslim consumers Halal food is an essential part of life. This is obvious from the fact that the word in Arabic denotes permissibility and that its opposite Haraam connotes impermissibility. With the Halal certification industry globally surpassing by far the value of both Kosher and Organic certified food and beverage markets, the interest towards Halal is at an all-time high. This has brought with it an on-going establishment of numerous Halal standards, the start of accreditation activities, the acknowledgement of dominant standards and industrial best practices.5 Due to the rapid growth and development of the Halal food sector, the expectation to Halal credence quality and its perception seem to be at a shift, namely, extending to include the principle of Tayyib. This is reflected by recent academic work especially on Halal integrity and Islamic economy reports suggesting Tayyib to be a new trend and a value adding factor in marketing Halal products.6‒10

The Tayyib concept has a wide scope under which various food sector issues could be discussed,11‒13 however, this paper will cover the aspects of food safety. For a Muslim consumer a food is safe for consumption if it complies with requirements set by the fundamental sources of Halal and Haraam Jurisprudence, namely the Quran and the Sunnah. Sunnah is the sayings, practices and approvals of the Prophet (P.B.U.H.) that have legal content but when it comes to the form of mere text then it is called Hadith.12 In the context of this paper food safety will be referred to as a concept that focuses on food that is injurious to health.14,15

The actual aim of Halal certification is to promote trade and maximise consumer choice. However, the varying scopes of Halal standards and ways of recognising Halal certification bodies have led to an overall global diversification of the Halal sector, possibly leading to the reduction of trade, limiting consumer food choice and the emergence of different interpretations.7,16 Food safety (Tayyib) in the Halal sector is an emerging area with differences in understanding and practicing the concept. While some say, it is a part of the sector others do not.9 Additionally, even if some Halal standards demand a certain level of food safety, it is even less clear how these are translated to the Halal certification bodies’ control measures during the certification process.17,18 This situation is worrisome especially because Muslim and even some non-Muslim consumers perceive the “Halal” mark to encompass food safety activities among others.9

The paper aims to explore whether and to what extent food safety is a part of the Halal and Tayyib concept and how that is currently backed up by the Halal food sector. The findings will enable to move toward more efficient Halal and Tayyib policies and improve the food sector´s practices.

fundamentals of halal–food sources

Making sure that food, its ingredients, additives and processing aids are of the proper source and treatment is the starting point for the Halal food sector. With the onset of processed foods, it has become difficult, even nearly impossible for the consumers by themselves to have information and clarity of the origins of substances added to food, especially when it is not compulsory to declare all of them.19 Thus, a need of competency, vigilance and a great responsibility lies on Halal certifiers. Interestingly enough, even though the sector has adopted itself the name “Halal”, it is inherently encompassed by a wider concept called Tayyib. Namely, to declare any food source as prohibited, the crux is its non-Tayyibness.11–13 This is also the basis on which some of the requirements brought out below are derived from. In Halal related literature, the discussion often revolves around the main prohibitions, namely the consumption of pork, blood, carrion, and animals not slaughtered according to Islamic requirements, intoxicants and products thereof.12 In addition to what is explicitly prohibited, there are also other nuances, like a mammal or bird amongst the land animals and their products, like eggs and milk, to be deemed as suitable for Muslim consumption they should be solely herbivores (e.g. sheep, goat, camel, cattle, rooster, pigeon, dove, quail and sparrow). This is explicitly promulgated by the following:

In Islamic Jurisprudence carnivores and omnivores are not considered Tayyib for consumption. This is because carnivores are predators; they eat from the flesh of other animals and omnivores have the aspect of carnivores as they are opportunist and at times also eat from the flesh of animals. In addition to obtaining food from a permissible source, mammals and birds need to be properly slaughtered. In this process the trachea, oesophagus, carotid arteries and jugular veins are severed without injuring the spinal cord.21 This process has been exhibited in Table 1.

In the herbivore category, there are some amount of mammals that are not permissible, like donkey and elephant. Donkey has explicitly been prohibited by the prophet (P.B.U.H.) and it is fundamentally used for loading while elephant cannot be slaughtered according to the Islamic principles due to its physics.12 Variety of interpretations prevails regarding aquatic animals but only fish with scales is unanimously allowed.12 Permissibility of arthropods is also a diverse topic, however, all the venomous species are unanimously deemed as non-Halal and locust as Halal. Furthermore, all the amphibians are deemed as non-Halal and among the reptiles only Dhub lizard (spiny-tailed lizard) is considered as Halal. Toxic and intoxicating substances are also impermissible, which is also the case regarding food of plant origin and drinks. 12,13

It becomes apparent from the above mentioned requirements that Islam only permits what it considers safe and suitable for consumption and the same has been demonstrated by laying down the principle of Tayyib. Furthermore, the above mentioned requirements are only covered by Halal certification and are thus rightly the main emphasis in Halal standards, certification and policies. This is also coupled by the fact that food safety already has its own constantly evolving practices in place, which bolster the Halal sector.

Understanding the principle of tayyib

Having clarified the fundamental requirements that set the foundation of Halal, this paper will continue by focusing on how Tayyib lays down the principle of food safety. Firstly, it is important to understand, that the Quran is the book of principles and fundamental guidelines leading people in all trades of life and Muslims are expected to use the best possible measures to comply with them, which becomes apparent from the verse (10:37) in the Quran. The most relevant verses to explain the Tayyib concept are brought out in Table 1. With the verse (2:168) the Quran lays down the principle of Tayyib regarding eating. In this verse, “lawful” is the translation of the Arabic term “Halal” while “good” is the translation of Arabic term “Tayyib”. Thus, the verse states that in order to consume a thing it must not only be Halal but it shall also be Tayyib. In the verse (7:157), Tayyib or “good things” are contrasted against the Arabic word “Al-Khaba’ith”, which is translated as “the evil”, meaning things that are impure, disgusting and harmful.21 Therefore, this verse states a ruling that impure, abominable and harmful things or in other words what is opposite of Tayyib are unlawful to consume.12 This is also supported by the classical definitions of Tayyib, which are as follow:

The fact that food safety is an intrinsic part of Halal is further strengthened by the verse (2:195) in the Quran, stating that people should keep away from every kind of destruction, including harm from food. In food sector the verse (2:195) can be translated as to prevention from and avoiding the hazard, which is defined as an agent that is reasonably likely to cause illness or injury in the absence of its control. It is categorised as biological, chemical and physical hazards. From the biological, physical and chemical type of hazards biological ones especially pathogenic bacteria are most common and have caused the most harm to consumers.26 Therefore, it is obvious that during any kind of food handling, hazards should be well understood and best possible measures taken to prevent them. Furthermore, this verse ensures food handlers a safe and sound working atmosphere.

Since Tayyib sets the general principle for assuring food safety in the Halal sector, all other texts regarding Islamic Jurisprudence reflecting measures of guidance towards a better food safety performance, will be expanded upon as a part of the Tayyib scope

Food safety measures in islamic jurisprudence

It is apparent that Halal food production should comply with both Halal fundamental and food safety requirements. Therefore, it is important to consider how Halal standards and policy makers and especially certifiers would be able to successfully enforce the implementation and maintenance of these two great areas and accordingly educate the food handlers. Especially since research to comprehend Halal compliance itself is lacking. There have only been a few studies on the issues arising during Halal production10,27,28 and on barriers and success factors to Halal assurance management. 29–33 Thus far this paper has examined the fundamental food sources of Halal, followed by a more focused discussion on how food safety is associated with the concept. Since Islamic Jurisprudence also offers some more detailed guidance relevant to food safety, these will be discussed in this paper, as they constitute an inherent part of the Halal and Tayyib concept. This will be of value in guiding the discussion around the conceptual framework and making recommendations for possible assurance approaches. For the sake of clarity relevant measures were grouped according to their content as follows:

These all lead a food handling company towards a better food safety performance and with that enables them to prevent harm coming to the consumer.

Before elaborating on the specifics, it is important to understand, that purity, cleanliness and hygiene are centric in Islam which becomes apparent from the Hadith, in Table 2.20,34,35 Purity, cleanliness and hygiene have been emphasized from its onset, since among the earliest revelations to Prophet Muhammad (P.B.U.H.) was the verse “And so your clothes purify.”22 The phrase “pure”, includes every kind of purity like good character, clean clothing, personal hygiene and cleanliness of the surroundings among others. Therefore, in general food-handling setting, its surroundings and food-handlers should maintain a constant state of the best possible purity. Cleanliness and purity from a food safety perspective lead to a higher level of hygiene and through that potentially lower occurrence of food borne disease.36

Operational environment hygiene

Surroundings have a great impact on people’s health and wellbeing. Clean environment is also a crucial aspect in achieving a high level of food safety. . Contamination of the food-handling environment has to be prevented, which in turn enables to prevent the contamination of products.14,15 A fundamental aspect of Tayyib is cleanliness and hygiene of the surroundings. It would be identified from the quoted Hadiths that Islam is very much sensitive regarding the environment outside the food establishment in routine course of life, hereafter it can be imagined that how more it will be thoughtful with respect to operational environment, therefore these texts will be translated from the routine course of life to the food establishment’s operation environment hygiene. From a food safety perspective, the Hadiths on purity in Table 2 emphasize the importance of achieving and maintaining a hygienic food-handling environment. The Hadith and highlight respect towards cleanliness of public places.37,38 The Hadiths, and part of the third Hadith are about removing anything that is disturbing to human health, environment and common taste, like garbage, waste, sewage among others, from the surroundings.20,37,38 From the Hadiths and it is clear, that the dryness of the soil is an indicator of its cleanliness and that clean earth could be used to clean ones self from impurities.39 Therefore, food-handlers should have proper respect for their work place, keep it clean and tidy. The food-handling area and equipment should be kept in a hygienic state, free from excess things and take precaution against pest, waste accumulation, leakages and any kind of mess and negligent storage. Food-handling establishments’ floors should allow adequate drainage and cleaning. Overall, the design and layout should create a hygienic environment to conduct proper food handling operations.

Personal hygiene

According to verses (9:108, 4:43, 5:6) in the Quran, bodily cleanliness is a vital daily practice in Islam. These verses in addition to Hadiths in Table 3 highlight bodily hygiene and the importance of using water when cleaning ones’ self,39,40 keeping clean after using the toilet, washing hands up until the elbows and feet up until the ankles, washing the face, neck and ears and rubbing the head with water. The Hadith additionally highlight personal grooming,35,37–39 especially taking care of any kind of hair on the body and nose and mouth hygiene. Siwak or tooth stick has a significant place in Islamic hygiene practices. It is an inexpensive, simple tool to take care of oral hygiene.41 Other methods, like tooth brush could be used as well. These injunctions have primarily been promulgated to the mankind in his individual and personal life but all are more needed in his social and collective life. These are all relevant aspects, which would positively impact a food-handling companies’ overall level of food safety.42 From fingernails to the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, people carry with them a reservoir of hundreds of different microorganisms with some being naturally present and others obtained through daily activities, with some of them being supportive to our bodily functions and others destructive. Concerning the outer surface of the body face, neck, hands and hair harbour a higher amount of microorganisms compared to other parts.36 Daily bathing of a food handler has been suggested as a measure to achieve a sufficient level on personal hygiene, since it directly influences the type and the amount of microflora on the skin.43,44 It is clear that personal hygiene concerns in the food industry are addressed by the Tayyib concept. On the other hand, current industrial best practices are important in achieving its proper assurance in the Halal food industry. Keeping the mouth and nose clean and healthy and regularly brushing teeth considerably reduces the amount of microorganisms present and with that the degree of potential food contamination. Eyes and ears of the food handler are not considered as a serious source of contamination, if not infected. On the contrary, mouth and nose contain significant amounts of microorganisms, which have also been found from food handlers’ hands during food preparation.36

Hand hygiene and faecal contamination

From the texts in Table 4, it becomes obvious that despite the focus on food-handler hygiene, the Tayyib concept zooms in on hand washing practices and protecting ones’ self from faecal matter. Poor food handler hygiene, especially lacking hand washing is deemed one of the main causes of food borne disease.36,45 the skin through everyday activities. They reside on the superficial layers of the skin and are also removable through routine hand hygiene practices.14,15,36 Washing three times indicates a longer duration and rubbing of hands during washing and washing in between the fingers indicate sensitive regions of the hands that are easily contaminated, hence these must be cleaned.35,40 Washing hands before and after being in contact with food indicates proper timing of hand washing. These constitute valuable advice to achieve clean hands and avoid cross-contamination in a food handling setting.39

A wide range of pathogens has been identified in faecal matter, which makes faecal contamination of food- handlers a great concern.36,43 Food-handlers’ clothes not to mention hands could come in contact with faecal matter when using the toilet. This could in return lead to the contamination of work surfaces and equipment when a worker moves around the factory. Hands may come in contact with these areas and finally transfer pathogens to food.36 It is of the utmost importance that food-handlers would avoid contact with faecal matter. This is also promulgated by Hadiths in Table 4.35,37,38,40 Before leaving the toilet, food-handlers should make sure their hands and clothes are clean.

Other cross-contamination issues

Table 5 indicates a focus on some specific cross-contamination issues relevant in the food safety context. Namely, the importance of proper work clothing, correct storage and packaging. Firstly, according to the verse (74:4) in the Quran, which has already been highlighted in the beginning of this section, and the Hadith,46 food handlers should wear suitable protective work clothing and be provided with adequate facilities to change in a clean manner without contamination. Wearing white clothes is also widely practiced in food establishments, mainly because it allows evaluating their cleanliness and deciding upon a time to change them. Regarding proper storage and packaging, contamination of food could also take place through touching or wiping the mouth or nose, coughing, sneezing or spitting. During coughing and sneezing droplets from mouth and nose could travel a significant distance and contaminate the surrounding workers, food and equipment.36 Therefore, if a food handler should take care not to breath, let alone sneeze or caught, into their own vessels, they should take extra care not to do that into other containers. This is highlighted in the Hadith.35 The Hadith indicates that containers and finished products in a food handling setting should be kept covered and raw material and final product packages closed.20 In addition, packages, both raw material and final product, should have a proper design to protect products from contamination from air, pests and a wide range of other hazards. These all constitute valuable advice to prevent cross-contamination in a food handling setting.

Assuring tayyib in the halal food sector

Keeping the above jurisprudential discourse in mind, for the first time this paper puts forth a detailed account of how food safety and hygiene form an intrinsic part of Halal assurance. Therefore,

Take the role of Halal food manufacturing prerequisites or for short Halal prerequisites. These requirements apply for the whole food sector and do not change with regards to what is being produced. Thus, these should be rooted in Halal standards, Halal certifiers’ control and food production companies´ and assurance practices. Therefore, before making any further conclusions and recommendations regarding Tayyib assurance in the Halal food sector the next section puts forth food safety and hygiene requirements in Halal standards and certification, in order to see whether they reflect the intrinsic values of Halal credence quality.

Halal standards and certification

Food safety and Halal standards are a part of third party certification schemes. Third party certification is often used to remedy transparency shortcomings and with that loss of trust in the supply chain.47,48 At present an official benchmark Halal standard does not exist, which leads us to explore food safety requirements in different Halal standards.7 At present, globally leading Halal standards are OIC/SMIIC 1:2011,49 which is aimed to become internationally accepted and the Malaysian governmental standard MS1500:2009, which is considered as industry’s best practice and serves as a basis for various other Halal standards.49 In recent years, new national Halal standards have been released by Pakistan in 2016 and United Arab Emirates (UAE.S 2055 -1:2015) in 2015.51

The OIC/SMIIC48 and PS50 Halal standards include CAC hygiene principles and ISO52,53 standards, define PRPs and the cold chain and finally specifically elaborate on hygiene practices. This is because the Pakistan standard is somewhat based on the OIC/SMIIC49 standard, however it additionally includes a conformance clause with applicable regulatory food safety requirements.50,52,53 The Malaysian standard also includes regulations and contains some detailed requirements for a hygienic food handling environment and practices.54 The UAE.S 2055 -1:2015, however, refers to the Gulf Standardization Organization’s GSO 1694: General principles of food hygiene standard, without giving any specific guidance on hygiene or other food safety measures.51

As for Halal standards on logistics and the supply chain, the IHIAS 0100:2010 standard highlights PRPs, maintaining the cold chain in addition to referring to the MS1500:2009 and ISO 22000 standards.55 Additionally, the Malaysian Halal-Toyyiban assurance pipeline standards for transportation, warehousing and retailing demand compliance with the MS54 standard and repeats its requirements on premises and personnel hygiene, health status and personnel cleanliness, in addition to defining and demanding compliance with the Tayyib concept. The Malaysian Halal-Toyyiban assurance pipeline standards define the Tayyib concept as follows:

“Complements and perfects the essence (spirit) of the basic standard or minimum threshold (halal), i.e. on hygiene, safety, sanitation, cleanliness, nutrition, risk exposure, environmental, social and other related aspects in accordance to situational or application needs; wholesomeness.”.56–58

It is obvious that food safety is in one way or the other a part of the major Halal standards. However, this is with considerable variation and insufficient detail, considering the inherent detail of the Halal prerequisites. In Halal standards, a trend seems to be to include compliance with international acknowledged general hygiene guidelines and food safety standards to assure Tayyib. The OIC/SMIIC48 has included ISO52,53 standard giving it a great significance in the Halal arena.

Even if the standards were to be sufficient, it is completely a separate matter how Halal certification takes place. The time of the audit, number of auditors and the emphasis of the audit have a great impact on not only how Halal fundamental requirements are assessed, but also on whether food safety is included in the assessment or not.17 highlighted that multiple Halal standards cause ambiguity in Halal certification.17 This is coupled by the fact that there are a vast number of certifiers who are of different size and competency and that, new Halal standards might raise adoption and implementation issues.

At present, it is unclear to what extent food safety requirements are considered during the Halal certification process. No set of documented procedures exist on how much time and effort should go into evaluating compliance with Halal requirements during Halal certification, let alone how big a part of it should food safety assessment be. Although, food safety management systems, food safety regulations and food codes cover the food supply chain, despite that foodborne disease outbreaks are not only still occurring in large numbers, but are also associated with companies, which have previously passed food safety controls with successful results.59,60 The on-going struggle with foodborne disease, varying uptake of food safety standards, drawbacks in food safety assessment and from country to country changing food safety approaches, scopes and enforcement possibilities should be a clear sign to the Halal sector that food safety issues are not to be ignored.61–64

Generally, food-handling companies are forced to have at least some kind of food safety measures in place by the government or a customer, inevitably forming a baseline of food safety for the Halal sector. Due to these existing food safety measures, the Halal sector anyway assures both Halal and Tayyib. There is just the question of extent and efficiency. However, it is important to differentiate that if the Halal certifiers do not assess food safety issues during audits, the Halal certificate itself does not reflect Tayyib control practices.

If Halal certifiers were to rely on checking for the existence of food safety certificates, they should take into consideration that this kind of third party certification only gives a snapshot of the food safety situation in a company, not demonstrating its daily practices. Additionally, even within the same food safety certification schemes there are significant inconsistencies in auditing quality.64,65 However, it is reassuring that companies with food safety certification have better food safety measures in place compared to non-certified companies.51,66 Furthermore, research has shown that the size of food-handling companies also affects their food safety performance. Namely, small and medium sized enterprises (SME) have been shown to have difficulty in implementing and maintaining food safety measures.67–70 Therefore, it is important for Halal certifiers to demand a reputable accredited auditing organization to back up a food-handling company’s food safety certificate.63 To completely take advantage of food safety certification, Halal certifiers should review the results of the food safety audit; understand the risks addressed by the standards and make risk-reduction decisions based on the results.59 Regarding the SME the Halal certifiers should not only be more cautious about food safety, but also for Halal criteria implementation.

Halal prerequisites and HACCP

This paper takes a step even further and puts forth the concept that Halal prerequisites should be implemented as Halal Control Points (HCP) in addition to Halal Critical Control Points (HCCP). The HCCP reflects the fundamental Halal requirements discussed above. Thus far, previous studies have suggested using the HACCP system for only HCCPs. A breach of HCCPs has been characterised as leading to critical failure, in which case the product would lose its Halal status.71 On the other hand, breach of HCPs would not result in complete rejection of the product, but it would give valuable insight on how well Halal assurance measures are in place and whether there is a need for improvement.

To the best of our knowledge for the first time, this paper offers a more detailed approach to the concept of HCPs and puts forth HCP for personnel hygiene and production environment sanitation, which apply for the whole Halal food sector. Taking into consideration the previous discussion on food safety measures in Islamic Jurisprudence, HCPs in a food handling setting would encompass the following:

Since avoiding faecal contamination in Halal production is an important concern, these HCPs could be added as an extra precautionary measure.

Thus, HCPs should be included to the Halal HACCP system principles. This would take the following form:

The HCPs mentioned so far concern employee hygiene, safety and production environment sanitation; however, different food sectors have additional specific HCPs (Table 6), (Figure 1). These, sector specific HCPs should be implemented in addition the Halal prerequisites discussed earlier.

The HACCP system is seen as a solution to achieve a better food safety performance, which thus makes it appealing to the Halal sector as well. However, there is some drawback. Firstly, effective application of HACCP requires thorough theoretical and practical knowledge from both Halal certifiers and food-handling companies. Unfortunately, this is not what the food sector currently reflects.64,72 In turn, Halal assurance might not get the desired effect or even worse lead to a false sense of security. Secondly, adjusting the HACCP system to include Halal would require an extra amount of different controls, which could be difficult to manage and time-consuming to control, leading to a decrease in both Halal and food safety performance.73 In this case, the companies could consider hiring extra personnel and might prefer to establish separate HACCP systems for food safety and HACCP. This is definitely an area, which needs further research.74,75

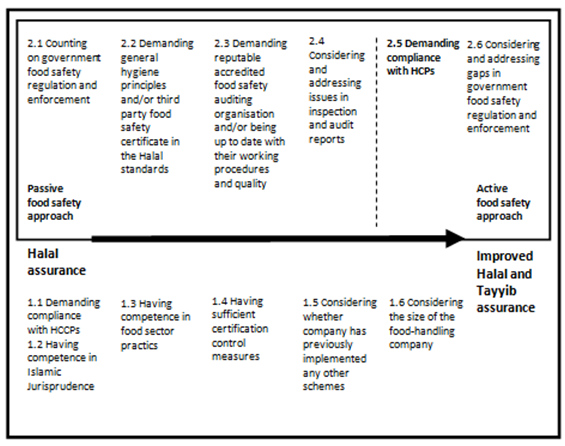

Construction of the conceptual framework

As discoursed earlier that the number of people every year suffering from food borne diseases is without a doubt worrisome, especially with acknowledged food safety schemes and measures being widely used by the food sector. From the Halal perspective, this is important because in addition to its foundational requirements Halal is encompassed by the Tayyib concept, which stipulates food safety. Generally, food-handling companies are forced to have at least some kind of food safety measures in place by the government or a customer, inevitably forming a baseline of food safety for the Halal sector. Therefore, for the Halal standards makers and certifiers it is suggested to take advantage of already existing food safety practices and research, instead on pursuing the same goal separately and by doing that not to depend exclusively on food safety certificates but it is advised to follow the complete process. This would allow transforming the Tayyib concept from theory to reality, which is also suggested by the conceptual framework (Figure 2).

The fundamental requirements, namely the HCCPs (Figure 2) form the foundation and the main emphasis of Halal standards and certification. Food safety (Tayyib) fits into that scope as a passive or active approach. The foundation requirements in the conceptual framework are depicted as HCCPs, because whether or not there is a documented HACCP system for Halal in place, these remain critical points for Halal assurance in any case. However, to uphold these requirements and to improve Halal assurance the standards should demand and the certifiers should have competence in Islamic Jurisprudence (1.2), like appointing an Islamic affairs advisor, and food sector’s practices (1.3), like appointing a food scientist, and have in place sufficient control measures (1.4), like audit lengths, number of auditors, their competency and a notification policy. Additionally, taking into account whether these companies have previously implemented any other schemes (1.5) and the size of food-handling companies (1.6) would give some insight on how well companies might adopt with the Halal concept and enable Halal certifiers to modify their approach accordingly. This would ultimately enable to achieve a better Halal and Tayyib performance.

Within the Halal assurance scope, food safety might have a passive or an active position in the standards and the certification process. The passive approach depicts the current situation in which food safety issues are minimally considered. In this case, Halal assurance relies on the existence of food safety certificates, hygiene principles and regulations (Figure 2). Since food safety is an intrinsic part of the Halal concept, it is discouraged and mentioned in this portion to compare it with the active approach, which is the main theme of conceptual framework.

In Halal standards, a trend seems to be to include compliance with international acknowledged general hygiene and food safety standards to assure Tayyib. For example, the OIC/SMIIC48 has included ISO52 standard giving it a great significance in the international Halal arena. The fact that companies, which have implemented food safety schemes, have been able to achieve a better food safety performance is reassuring. Despite that, Halal certifiers should be cautious regarding possible control measure inconsistencies within the same scheme and take into consideration that this kind of third party certification only gives a snapshot of the food safety situation in a company, not demonstrating its daily practices. Therefore, as a minimum the Halal standards and certifiers should demand a reputable accredited auditing organization to back up a food-handling company’s food safety certificate (Figure 1), in addition to considering and addressing issues in food safety inspection and audit reports (2.4). Additionally, for the third party food safety certification to be of use Halal certifiers should:

Such details are not given in Halal standards. Therefore, it remains unclear how the prescribed food safety measures are exactly incorporated into Halal control processes. Thus, it could be inferred that the current Halal food control practices incline toward the passive Halal and Tayyib food safety approach.

Including food safety assessment into the Halal certification process activities would render the Halal certificate to reflect Tayyib control practices as well. In this case, Halal certifiers would be more concentrated on what is happening in the sector by taking into consideration and addressing various food safety issues. The HCPs (Figure 2) could offer a valuable starting point and a guide to focus Halal control practices regarding food safety, without losing sight of primary aspects, namely the HCCPs. This would lead to upholding the integrity of both the Halal and Tayyib concept and allow to place a “Halal and Tayyib” label on product packaging. By addressing HCPs food-handling companies’ would improve their food safety performance, since hygienic practices, specifically hand washing, are crucial in preventing foodborne disease. This would ultimately lead to safer final products justifying non-Muslims’ preference of Halal products.76,77 Consider gaps in governmental food safety regulation78–80 and enforcement (2.6) would even more further Tayyib assurance practices. The active Halal and Tayyib food safety approach is definitely something the Halal food sector should strive toward. The implementation and control of HCPs, being an inherent part of the Halal and Tayyib concept, would lead to not only a better food safety compliance, but also to properly following the Halal and Tayyib requirements.

Figure 2 A conceptual framework is presented for Halal foundation and assuring Tayyib from a food safety perspective in the Halal food sector.

Chapter and Verse from the Quran |

Relevant Texts |

2:168 |

O mankind, eat from whatever is on earth [i.e.,] lawful |

7:157 |

And makes lawful for them the |

2:195 |

And do not throw (yourselves) by your (own) hands into |

Table 1 Texts from the Quran regarding the Islamic food safety principle of Tayyib

Collector and number of Hadith |

Relevant Texts |

Reference |

Sahih Muslim,20 1015 |

Allah is pure and He accepts only what is purely good. |

20 |

Sahih Muslim,20 223 |

Purity is half of the faith. |

20 |

Nasa’i,35 77 |

Come to a means of purification and a blessing from Allah. |

35 |

Ibn Majah,37 328 |

Discharging oneself in watering places, |

37 |

Sahih Muslim,20 550 |

Abu Huraira reported that the Messenger of Allah (P.B.U.H) |

20 |

Sahih Muslim, 20 553 |

Abu Dharr reported: The Prophet of Allah (P.B.U.H) said: |

20 |

Ibn Majah,37 3681 |

Remove harmful things from the path. |

37 |

Sahih Muslim, 20 35 |

Faith has over seventy branches or over sixty branches, |

20 |

Abu Dawood,39 382 |

The earth becomes Pure when dry. |

39 |

Abu Dawood, 39 386 |

When any of you treads with his shoes upon something unclean, |

39 |

Table 2 Texts of Hadith regarding the hygiene of food handling environment in Islamic Jurisprudence

Collector and number of Hadith |

Relevant Texts |

Reference |

Tirmidhi,40 33 |

The Prophet wiped his head two times: He began with the rear of his head, then with the front of his head and with both of his ears, outside and Inside of them. |

40 |

Tirmidhi, 40 36 |

The Prophet wiped his head and his ears: the outside and the inside of them. |

40 |

Abu Dawood,39 132 |

Narrated Talhah ibn Musarrif that I saw the Messenger of Allah wiping his head once up to his nape. Musaddad reported: He wiped his head from front to back until he moved his hands from beneath the ears. |

39 |

Ibn Majah,37 294 |

Part of the nature is rinsing out the mouth, rinsing out the nostrils, using the tooth stick, trimming the mustache, clipping the nails, plucking the armpit hairs, shaving the pubic hairs, washing the joints, washing the private parts and circumcision. |

37 |

Nasa’i,35 02 |

When the Messenger of Allah got up from sleep, he would brush his mouth with the Siwak. |

35 |

Sahih Muslim, 20 238 |

When any one of you wakes from the sleep, he must clean his nose three times. |

20 |

Abu Dawood,39 4163 |

He who has hair should honour it. |

39 |

Table 3 Texts of Hadith regarding food handler personal hygiene in Islamic Jurisprudence

Collector and number of Hadith |

Relevant Texts |

Reference |

Nasa’i,35 01 |

When any one of you wakes from sleep, let him not touch anything with his hands (for consumption or for any other use) until he has washed it three times, for none of you knows where his hand spent the night. |

35 |

Tirmidhi, 40 38 |

While washing hands, go between the fingers. |

40 |

Abu Dawood,39 3761 |

The blessing of food consists in washing hands before and after it. |

39 |

Ibn Majah,37 348 |

Most of the punishment of the grave is because of urine. |

37 |

Tirmidhi,40 70 |

The Prophet (P.B.U.H.) passed by two graves. Thereupon he said that these two are being punished. He (P.B.U.H.) added, “as for this one, he would not protect himself from his urine. As for this one, he used to spread Namimah (slander).” |

40 |

Nasa’i,35 47 |

Do not wipe yourself with right hand. |

35 |

Sahih Bukhari,38 5376 |

Mention the Name of Allah and eat with your right hand, and eat of the dish what is nearer to you. |

38 |

Table 4 Texts of Hadith regarding hand hygiene and faecal contamination in Islamic Jurisprudence

Collector and number of Hadith |

Relevant Texts |

Reference |

Riaz us saliheen,46 02 |

Wear white clothes because they are the purest and they are closest to modesty. |

46 |

Nasa’i,35 47 |

When any one of you drinks, let him not breath in to the vessels. |

35 |

Sahih Muslim,20 2012 |

Cover vessels, water skins, close the doors and extinguish the lamps. |

20 |

Table 5 Texts of Quran and Hadith regarding some cross-contamination issues in Islamic Jurisprudence

No. |

HCCP |

HCP |

1 |

The animal/bird to be slaughtered shall be halal |

Merciful treatment of animals, hence, they must be treated as such that they are not stressed or excited prior to slaughter. Holding areas for cattle should be provided with drinking water, animals should be nourished and well rested. |

2 |

Only animals/birds fed on Halal feed are permitted for slaughtering |

Hygiene and sanitation of personnel and the production environment, including sufficient sanitation schedules, cleaning procedures and instructions, lavatory and hand washing facilities, detailed personal hygiene and hand washing instructions and clean work clothing. |

3 |

The animal/bird to be slaughtered shall be alive at the time of slaughter |

The slaughter knife must be sharp. The size of the knife (blade length) should be proportioned to the size of the neck. The knife must not be sharpened in front of the animal. |

4 |

The slaughterer shall be a profound Muslim |

It is preferred that the animal would be faced towards Qibla during slaughter. |

5 |

The slaughterer shall invoke the name of Allah while severing the trachea, esophagus and both the carotid artery and jugular vein. |

When the bleeding has ceased, the heart stops, and the animal is dead, one may start further acts of processing the carcass. It is abominable to sever parts such as ears, horn, and legs before the animal is completely lifeless. |

6 |

Packing is done to clean packages and boxes, and proper labels are affixed to facilitate traceability. |

|

7 |

Packages/ containers/ vessels of ingredients, additives, processing aids and products at any stage of production should be kept covered/closed and proper clean packaging used. |

|

8 |

|

Ingredients, additives, processing aids and products at any stage of production should be properly stored. Halal and non-Halal ingredients should have their designated areas. Halal and non-Halal food should not be placed or stored side-by-side and non-Halal products on top of Halal products. |

Table 6 HCCPs and HCPs in Halal meat and poultry slaughter

The research on food safety and hygiene requirements in Halal food production lead to the formation of the concept of Halal prerequisites. These are an intrinsic part of the Halal concept, which should be implemented throughout the sector to achieve both Halal and Tayyib assurance. This paper also suggests the HCPs as an addition to the HACCP Halal system. In which case, the Halal prerequisites would be incorporated as HCPs to the system along with the sector specific HCP, like in the meat and poultry production. Incorporating either the specified Halal prerequisites or the HCPs to Halal standards and Halal certification procedures, would allow transforming the Tayyib concept from theory to reality. Since currently, the Halal certifiers have a passive approach towards Tayyib assurance. They rely on just the existence of food safety certificates and regulations and in this case, the certificate itself does not reflect Tayyib control practices during Halal audits.

Although, food safety and hygiene (Tayyib) are an intrinsic part of the Halal concept, Halal standards lack details on the subject and quote general hygiene principles and food safety standards. Therefore, as a minimum, checking the food certification reports and governmental inspection reports should be included in the Halal standards and certification process. However, including food safety assessment into the Halal standards and certification process would render the Halal certificate to reflect Tayyib control practices and the Halal food sector to have an active approach toward Tayyib assurance. In order to do that the Halal standards makers and certifiers have to consider Halal prerequisites. These offer a valuable starting point and a guide to focus Halal control practices regarding food safety. This would also enable food-handling companies to improve their food safety performance, since hygienic practices, specifically hand washing, are crucial in preventing foodborne disease. This would ultimately lead to safer final products justifying non-Muslims’ preference of Halal products.

None.

The authors’ don’t have any conflict of interest towards the publication of this paper.

©2018 Raheem, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.