Journal of

eISSN: 2373-4310

Review Article Volume 8 Issue 2

Ethiopian Meat and Dairy Industry Development Institute, Ethiopia

Correspondence: Demissie Negash, Ethiopian Meat and Dairy Industry Development Institute, PO Box 1573 Bishoftu, Ethiopia

Received: February 08, 2018 | Published: March 29, 2018

Citation: Negash D. A review of aflatoxin: occurrence, prevention, and gaps in both food and feed safety. J Nutr Health Food Eng. 2018;8(2):190 – 197. DOI: 10.15406/jnhfe.2018.08.00268

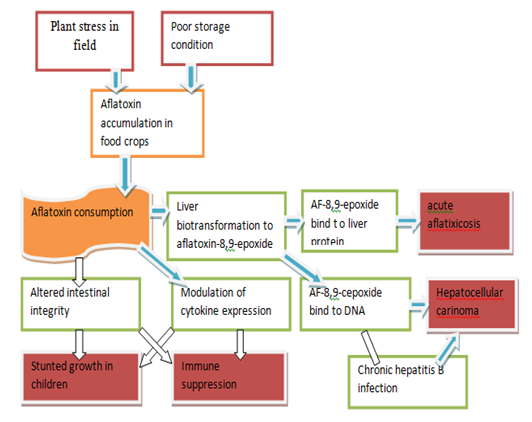

This review was conducted to investigate on Aflatoxin: occurrence, prevention, and gaps in both food and feed safety. Risk of aflatoxin contamination of commodities in the world, especially in Africa is increasing. Maize and grounds are the two crops mainly play an important role in the diets. The infection of these crops by aflatoxicogenic fungi and hence contamination with aflatoxin is generally higher. Consequently, the exposure of human and animals to this toxin is higher and cause huge health and economic problems. AFB1, AFB2, AFG1, AFG1, AFM1 and AFM2 are the most common type of aflatoxin. Aflatoxin contamination of agricultural commodities poses considerable risk to human and livestock health and economic losses. Exposure of human to aflatoxin leads to several health-related condition including acute and chronic aflatoxicosis, immune suppression, liver cancer, liver cirrhosis, stunted growth in children and many others. Aflatoxins are detected from several crops especially from maize and groundnut. Several researches show that AFB1 is the most common aflatoxin in the world from most commodities at a very much higher level. AFM1 was also detected greater than the standard from milk and milk products. This indicates that a lot of developing countries people are at danger of aflatoxin contamination. Lack of awareness on aflatoxin contamination increases the risk of damage to human and animals. High economic losses due to aflatoxin occur in the country crops and animals.

Keywords: aflatoxin, feed, food, occurrence, prevention

FAO, food and agriculture organization; EU, European union; FDA, food and drug administration; RASFF, rapid alert system for food and feed

Aflatoxins are one of many natural occurring mycotoxins that are found in soils, foods, humans, and animals. Derived from the Aspergillus flavus fungus, the toxigenic strains of aflatoxins are among the most harmful mycotoxins. Aflatoxins are found in the soil as well as in grains, nuts, dairy products, tea, spices and cocoa, as well as animal and fish feeds.1 Aflatoxins are especially problematic in hot, dry climates (+/- 30 to 40 degrees latitude), and their prevalence is exacerbated by drought, pests, delayed harvest, insufficient drying and poor post-harvest handling. Exposure to foods contaminated with high levels of aflatoxins can cause immediate death to humans and animals. Chronic high levels lead to a gradual deterioration of health through liver damage and immunosuppressant. Linkages with child stunting are suspected but not proven. Malaria and HIV/AIDS may also be affected by aflatoxin levels, though to date the evidence is inconclusive.

There are six forms of aflatoxin: B1, B2, G1, and G2 are found in plant-based food, while M1 (metabolite of B1) and M2 are found in foods of animal origin. B1 is the most harmful form due to its direct link to human liver cancer.2,3 Though aflatoxins are difficult to detect visually and also to contain, there are documented methods to prevent and mitigate the development and spread of aflatoxins.

Much of Sub-Saharan Africa is at risk of unsafe levels of aflatoxin exposure that can negatively affect human health, food security and economic trade Williams et al. In developing countries mycotoxins of greatest importance as aflatoxins are naturally occurring in agricultural products in which infrastructure, harvesting and storage/stock methods for foods are poor. These carcinogenic, mutagenic and teratogenic secondary metabolites are produced by several species of filamentous fungi Aspergillus sect. Flavi mainly A. flavus. Agricultural commodities such as maize and peanuts at different stages of food chain either pre- or post-harvest or might be excreted in hydroxylated form in milk and milk products can be contaminated by aflatoxins. Therefore, human exposure to aflatoxins both in un conjugated/conjugated forms is mainly through consumption of contaminated plant-derived and milk products as these compounds are resistance to heat within the range of conventional treatment temperatures. AFB1 as the most toxic and common aflatoxin induces primary liver cancer that exhibits synergistic activity with hepatitis B virus infection, where in Asian developing countries hepatitis B is prevalent.

Given that incidence of aflatoxins-producing fungi in crops is not exactly associated with increased contamination due to differences in virulence to host plants, competitive ability and other factors, the higher frequencies of aflatoxins-producing fungi leads to severity of contamination and finally the product losses. Production of aflatoxins is influenced by many abiotic and biotic factors; however, it is mainly reported to occur by high relative humidity and temperatures of unseasonal rains due to climate changes at the time of harvest. Occurrence and extent of aflatoxins contamination might also be associated with unsuitable cultivation, storage and transport conditions.

When any commodities are stored under high moisture and temperature conditions, aflatoxin contamination may occur. Other commodities such as cocoa beans, linseeds, melon seeds and sunflower seeds have been infrequently contaminated with mycotoxins with lower importance rate compared to other commodities.4 Aflatoxin is the most important contaminant on the Rapid Alert System for Food and Feed (RASFF) of the European Union in a way that in 2008, aflatoxins alone were responsible for almost 30% of all the notifications to the RASFF system (902 notifications).5 Completely to eliminate the aflatoxin toxicity or reduce its content in foods and feedstuffs in significantly levels, increasing knowledge and awareness on aflatoxins as a potent source of health hazard to both human and animals is a great deal of effort will necessary. Although prevention is the most effective intervention, chemical, biological and physical methods have been investigated to inactivate aflatoxins or reduce their content in foodstuffs.6

Aflatoxins are the fungal metabolites produced by some strains of Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus parasiticus. Aflatoxin is produced at a temperature of 12-40°C and requires 3-18% moisture.7 The four most common aflatoxins are B1, B2, G1 and G2, with the B1 most potent liver toxin and classified as class I carcinogen for humans. In animals, their effects vary with the dose, length of exposure, species, breed, diet or nutritional status. Generally, calves are more susceptible than older animals. It exerts carcinogenic, teratogenic, hepatotoxic and mutagenic effects and also suppresses the immune system of cattle. Aflatoxins exert acute and chronic effects in animals.8 According to Akandeat9 Aflatoxin can cause liver damage, cancer and drop in milk production, immune suppression and anemia. Furthermore, it is also associated with reduced feed consumption and overall retarded growth and development in dairy cattle. When the dairy animals fed with an aflatoxin free diet, milk production increased over 25%. Aflatoxin is excreted into milk within12 hours in the form of aflatoxin M1 with residues approximately equal to 1.7% of the dietary aflatoxin level. The FDA limits for aflatoxin M1 in milk is 0.5 ppb while for aflatoxin B1 should not be more than 20 ppb.

History of aflatoxins

Aflatoxins were discovered in 1960 when more than 100,000 young turkeys died in England over the course of a few months from an apparently new disease that was termed “Turkey-X disease”. It was soon found that the mortality was not limited to turkeys. Ducklings and young pheasants were also affected. After a careful survey of the outbreaks, the disease was found to be associated with the Brazilian groundnut meal. An intensive study of groundnut meal revealed its toxic nature as it produced typical symptoms of Turkey-X disease when consumed by poultry and ducklings. A study on the nature of the toxin suggested its origin from the fungus Aspergillus flavus. Thus, the toxin was named “aflatoxin” by virtue of its origin from A. flavus. This was the event which stimulated scientific interest and gave rise to modern mycotoxicology. Research on aflatoxins led to a “golden age” of mycotoxin research during which several new mycotoxins were discovered.10 Other important mycotoxins produced by Aspergillus, Fusarium and Penicillium include ochratoxin, patulin and fumonisins.10 Among all mycotoxins and polyketide compounds synthesized by fungal species, aflatoxins (the most potent hepatotoxic and carcinogenic metabolites) continue to receive major attention and are most intensely studied.

Conditions for aflatoxin contamination

The production of mycotoxins within the fungus depends on food sources and the particular enzymes of the fungus and other environmental factors.11 The growth of aflatoxicogenic fungi is directly related with the production of aflatoxin, so that conditions suitable for this fungal growth are favorable for aflatoxin production. Chulze12 reported that the primary factors influencing fungal growth in stored food products are the moisture content (more precisely, the water activity) and the temperature of the commodity. Food grains are normally harvested at higher moisture content and then dried to bring down the moisture content up to safe level before storage. Thus, delay in drying to safe moisture levels increases risks of mould growth and mycotoxin production

Aflatoxin infection occurs in crops prior to harvest and once the grain reaches storage. It can be produced when maturing maize is under drought and insect stress with prolonged periods of hot weather. Post harvest contamination can occur if crop drying is delayed. It can also occur during storage of the crop if moisture is allowed to exceed critical values.13 Payne14 also reported that a flatoxin contamination of maize before harvest has been associated with drought combined with high temperature as well as insect injury.

According to Schmale11 moulds produce aflatoxins under a wide range of conditions and, therefore, the potential for a challenge should always be considered with plant stress, harvest stress, storage stress and feed-out problems. A study by Lal.15 revealed that Fungal spoilage of stored commodities and aflatoxin production highly depends on several important factors including moisture content, relative humidity in the air and temperature of the environment under a production system with no irrigation, dryer soil conditions associated with higher temperature particularly after the peg development stage of groundnut favor infection by Aspergillus and the development of aflatoxin prior to harvest.

According to Strosnider some essential factors that affect aflatoxin contamination include the climate of the region, the genotype of the crop planted, the soil type, the minimum and maximum daily temperatures, and the daily net evaporation. Aflatoxin contamination is also promoted by stress or damage to the crop due to drought before harvest, the insect activity, a poor timing of harvest, the heavy rains during and after harvest, and an inadequate drying of the crop before storage.

Aflatoxin production in the grain can happen in the field in the storage conditions between 20 and 40oc with 10-20% of humidity and 70-90% relative humidity in the air. A. flavus has relatively high moisture requirements among storage fungi. Hence, aflatoxin contamination of grains is aggravated by high seed moisture. Aflatoxin contamination is a perennial risk between 40°N and 40°S of the equator.

Formation, toxicity, and regulation of aflatoxin M1

Milk has the greatest demonstrated potential for introducing aflatoxin residues from edible animal tissues into human diet. Aflatoxins are one of the major etiological factors in the development of hepatocellular carcinoma, and more recently associations between childhood aflatoxin exposure and both growth faltering16 have been reported. Moreover, as milk is the main nutrient for growing young, whose vulnerability is notable and potentially more sensitive than that of adults, the occurrence of AFM1 in human breast milk, commercially available milk, and milk products is one of the most serious problems of food hygiene. Some European Community and Codex Alimentarius prescribe that the maximum level of AFM1 in liquid milk and dried or processed milk products should not exceed 50 ng/kg.17 According to US regulations the level of AFM1in milk should not be higher than 500 ng/kg (Stoloff et al., 1991).18 There are thus differences in maximum permissible limit of AFM1 in various countries (Table 1).

Region |

Maximum acceptable Level (ng/l) |

Type |

European Union |

50 |

Milk |

Australia |

50 |

Milk |

Argentina |

50 |

Milk |

Bulgaria |

500 |

Milk |

Germany |

50 |

Milk |

Australia |

20 |

Children's Milk |

Sweden |

50 |

Liquid milk products |

Netherland |

20 |

Butter |

Switzerland |

50 |

Milk and milk products |

250 |

Cheese |

|

Belgium |

50 |

Milk |

USA |

50 |

Milk |

Czech Republic |

100 |

Children's Milk |

500 |

Adult's milk |

|

Serbia |

500 |

Milk |

Iran |

50 |

Raw, Pasteurized, and UHT milk |

200 |

Cheese |

|

20 |

Butter |

|

France |

30 |

Children's milk < 3 years |

50 |

Adult's milk |

|

Turkey |

50 |

Milk and milk products |

250 |

Cheese |

|

Brazil |

500 |

Milk |

Table1 Maximum acceptable level of AFM1

Regulatory limits seem to be a practical compromise between the need to have carcinogen free commodities and the economic consequences of setting regulatory limits.19 However, Stoloff et al.18 observed that as to aflatoxins there was little scientific basis, or the existing scientific information was not used in setting legal limits in most countries. Thus, even the low regulatory limits set by countries could not prevent chronic effects of aflatoxins, due to continued exposure to subacute levels of aflatoxins. Because of the following reasons, it seems that monitoring and preventive program are the most effective strategies to decrease the risk of exposure to both human and animals:

Aflatoxins occurrence in feeds

There are six common mycotoxins that affect animals: aflatoxins, fumonisins, ochratoxins (which like aflatoxins affect liver function), trichothecenes, and zearalenone. Diagnosis of aflatoxin exposure in animals is difficult, especially in large farms that use mixed feed, which may contain highly varied combinations of feedstuffs.

As in humans, animals exposed to high levels of aflatoxin-contaminated feed have been known to exhibit the severe form of “intoxication,” which can lead to death. Usually, however, exposure in animals is of a “sub-clinical” level, which leads to liver damage, reduced weight gain and lost productivity (declines in egg and milk production) resulting in economic losses to the industry. Aflatoxins affect livestock growth, reproduction, immune functioning and ability to metabolize vaccines.20 Poultry and fish are most affected, but there is also a lot of concern about B1 contamination in milk, given that it is often fed to infants and young children.2

The effects of animal feed on meat and other byproducts: Consumption of aflatoxin-contaminated animal feeds varies with preparation and the type of product. Anthony et al. reviewed studies in which the prevalence of aflatoxins was compared across beef and edible organs that were either fresh or sun dried. Consistently, organ meats (especially kidney) were more contaminated than beef, while fresh products (as opposed to sundried products) maintained higher aflatoxin contamination levels.

Time of harvest has been shown to be important in influencing the occurrence and levels of aflatoxin because Aspergillus does not compete well with other molds when corn presents more than 20% moisture. Harvesting corn when moisture content is above 20% followed by rapid drying to at least 14% moisture content within 24 to 48 hours of harvest can inhibit Aspergillus growth and toxin production. Contaminated grains and their byproducts are the most common sources of aflatoxin. Corn silage may also be a source of aflatoxins, because the ensiling process does not destroy toxins already present in silage.21

On the farm, more than one mold or toxin may be present in the contaminated feed, which often makes definitive diagnosis of aflatoxicos is difficult. The prognosis of aflatoxicos is depends up on the severity of liver damage. Once overt symptoms are noticed the prognosis is poor. Treatment should be directed at the severely affected animals in the herd and further poisoning prevented. Aflatoxicos is typically a herd rather than an individual cow problem. If aflatoxicos is suspected, feed should be analyzed immediately. If aflatoxins are occurred, the source should be eliminated immediately. Levels of protein in feed and vitamins A, D, E, K and B should be increased as the toxin binds vitamins and affects protein synthesis. Good management practices to alleviate stress are essential to reduce the risk of secondary infections which must receive immediate attention and treatment.21

Importantly, it has been demonstrated that simple measures can significantly reduce the risk of mycotoxin exposure on farm. Storage of grain at appropriate moisture content (below 130 gkg-1), inspection of grain regularly for temperature, insects and wet spots will limit the possibility of fungal development in feeds and feedstuffs as discussed before. The risk of feed contamination will be reduced in animal units with rapid turnover of feed because there will be less time for fungal growth and toxin production.22 Aflatoxin is just one of many mycotoxins that can adversely affect animal health and productivity. Care regarding animal feed must be extended not only to the nutritional and economic value, but also to food quality.23

The presence of molds in foodstuffs causes the appearance of flavors and odors that reduce palatability and affect feed consumption by animals as well as reduce the nutritional value of foods. Mycotoxins, in turn, affect the digestion and metabolism of nutrients in animal production, resulting in nutritional and physiological disorders, besides a negative effect on the immune system.28

Aflatoxins occurrence in animal products

When focusing on how mycotoxins play a role in food safety, attention should be limited tomyco toxins that are known to be transferred from feed to food of animal origin, as this food represents a significant route of exposure for humans.25 Apart from their toxicological effects in affected animals, the carry-over through animal derived products, such as meat, milk and eggs into the human food chains is an important aspect of mycotoxin contamination. FAO has estimated that up to 25% of the world’s food crops and a higher percentage of the world’s animal feedstuffs are significantly contaminated by mycotoxins.

Aflatoxin or ochratoxin residues in meat are uncommon and rarely found. However, it’s more common in organs especially liver. This organ may have its lipid content increased over three fold when 20 ppm aflatoxin is incorporated in broiler feed.26

The problem in the egg production is that the long-term or short-term hen’s exposure, via dietary sources, to low concentrations of certain mycotoxins causes contamination of eggs. This is the case of aflatoxins, which have a high impact in both, human and animal health, causing significant losses in the egg industry, considering the deleterious effect on egg production and quality. In laboratory studies it was proved that aflatoxin can decrease egg production and increase liver fat (fatty liver syndrome). This classical study established the typical symptoms associated with acute or chronic aflatoxicos is, observed until today in field conditions.27

A distinctive sequence of events during acute aflatoxicos is in laying hens (30 weeks-old) in a four week experiment with increasing aflatoxin doses in the diet of 0; 1.25; 2.5; 5.0 and 10.0μg g-1.28 Results indicated that egg production was decreased by about 70% from the control value at 10μg g-1 concentration in the diet and the liver size was increased significantly by 5 and 10 μg g-1 dietary concentrations of aflatoxin and the liver lipid increasing dramatically by a smaller dose of 2.5 μg g-1. Shows the dramatic effect of aflatoxin in the liver function.27 The obtained data suggest that plasma and yolk lipids respond to the inhibition of lipid synthesis and transport from the liver during aflatoxicos is induced by the dietary treatments. The liver malfunction results in an increase in its fat content and a decrease in the levels of plasma lipids.

A review carried out in Brazil29 showed high variability among the results. For instance, corn contamination with aflatoxins reached 906 ppb, above those levels allowed by legislation (20 ppb). This fact indicates the need for quality control in the reception of this ingredient in the feed mill with the use of rapid tests for mycotoxins. Regarding products of animal origin, major problems were not observed in eggs and tissues of swine and poultry. However, among chicken liver samples 50% tested positive but with relatively low levels. Anyway, attention should be paid with liver consumption when there are evidences of corn contamination.

In the last decades, only aflatoxins and, to a lesser extent, ochratoxin A were regulated in foods from animal origin. For other toxins, the risk management was based on the control of the contamination of food from vegetal origin intended for both human and animal consumption. Nowadays, other mycotoxins are included. Regulatory values or recommendations are mainly built on available knowledge on toxicity and potential carryover of these molecules in animal. Therefore, by limiting animal exposure through feed ingestion, one can guarantee against the presence of residues of mycotoxins in animal-derived products. However, accidental high levels of contamination may lead to a sporadic contamination of products coming from exposed animals.30

Tolerance levels of mycotoxins in foods are needed to ensure product quality and consumer health. The limits differ among countries, i.e., depending on the product and the country there are different tolerance levels for each mycotoxin, but it is certain that their presence in foods has been widely researched and new standards were required over the years, in the last decade.

Adsorbents are necessary and important and may have great impact on improving animal production and health, providing greater security to consumers of animal products, due to the reduction and/or removal of mycotoxins in these products.

Considering that aflatoxins were the first discovered mycotoxins, there are many data available searching for binders and other methods to reduce toxicity in animals. However, due to methodologies used for evaluation, there is certain degree of variation in results.

The most common additives used in animal diets are aluminosilicates, produced synthetically or extracted from clay mines. There are also other alternatives to reduce aflatoxin toxicity, as presented.

Many of the technologies for aflatoxin mitigation have been well documented in the recently released Synthesis of the Research on Aflatoxin in Health, Agriculture and Trade.3 This section also draws heavily from the analysis of Liu Y et al.31 What follows discusses the literature as it pertains to the potential feasibility of these solutions.

Pre-harvest solutions

As noted above, many of the pre-harvest solutions currently available are based on Good Agricultural Practices, which typically include use of insect resistant crops, good tillage and weeding practices, appropriate use of fertilizers, irrigation, and crop rotation.32 In addition to GAP, practices such as treating soil with lime and farmyard manure have proven successful at reducing aflatoxin contamination levels.33

Post-harvest stage

According to Cole et al.34 post-harvest screening to remove contaminated seed appears to be a promising means to reduce or to eliminate aflatoxin. When aflatoxin contamination occurs, there are usually only a few highly contaminated seeds irregularly distributed in the groundnut lots. Most of the harvested seeds are free of contamination. Early removal of high-risk seeds, e.g., those that are damaged, immature, or discolored, should be an effective way to prevent further contamination and increase the groundnuts’ value. Practical methods include manual sorting, seed size and density separation, or electronic color sorting. Electronic color sorting has proved to be the most effective aflatoxin management strategy available in the processing phase.

During the post-harvest stage, thorough drying, prompt storage and transport using clean, dry containers are the basic elements of aflatoxin prevention and control. Timely harvest is also critical for aflatoxin prevention. One study found that aflatoxins in maize increased 4-7 fold after a 3-4 week delay in harvest after maturity.35 IITA has made recommendations for aflatoxin mitigation in maize for subsistence farmers, who often lack the resources or access to drying and storage equipment. It based its recommendations on surveys with subsistence farmers throughout in Nigeria and other parts of Sub-Saharan Africa. Through these interviews, IITA identified some practices that were already being put to use which affected the levels of aflatoxin follow up tests.

The key elements of these recommendations include sorting, cleaning, drying, packaging, adherence to hygiene and sanitary conditions in storage and transport, as well as through raising farmers’ awareness about these practices.35 The recommended practices are documented below (Table 2).

Low aflatoxin levels |

High aflatoxin levels |

Production practice |

|

Crop rotation |

Maize mono cropping |

Local variety in South |

Improved variety in South |

Improved variety in North |

Local variety in North |

Maize in mixed cropping |

Cow pea, peanut or cassava intercrop |

Diammonium phosphate fertilizer |

No fertilizer |

Farmers aware of incomplete husk cover |

Maize is damaged in the field |

Harvest practice |

|

Harvest at crop maturity |

Delayed harvest |

Harvest of maize with the husk |

Harvest maize in heaps, cobs shelled later |

Sun drying on platformʺ Fieldʺ drying on the plant |

Delayed drying |

Drying of maize without the husk immediate removal of damaged cobs |

No storing at harvest |

Storage practice |

|

Cleaning of the storage structure |

No preparation of the storage structure |

Maize storage for 3-5 months |

Maize stored for 8-10 months |

Smoke or insecticide use |

No insect control |

Maize stored in aerated store |

Maize stored in poultry aerated stores |

Table 2 Farming practice associated with high and low aflatoxin levels in stored in bins crop rotation35

Clean, dry, insect and rodent free storage conditions are critical to prevent aflatoxin growth as noted by the USAID desk review. Making storage options inexpensive and accessible is of paramount importance for consistent, long term utilization. The USAID synthesis outlines broadly the various pre harvest and post-harvest methods.3

Turner also investigated low-technology post- harvest handling options for groundnut in an aflatoxin susceptible zone in Guinea. The package of interventions investigated included: hand sorting, storage in jute bags, education on improved sun drying, wooden pallets for drying, locally-made natural fiber mats and insecticides. The estimated cost of this intervention package was $50 (including $10 for the wooden pallet); a sizeable but potentially manageable cost where the GNP per capita is $1100.Five months after harvest, this combination of storage methods led to a 50% reduction of aflatoxin biomarkers among the households in the intervention group as compared to the control group.

Even in resource-constrained communities, there are several processing methods that can reduce aflatoxins in maize. The most promising processes reviewed included cleaning the cereal/groundnut by sorting, washing the food before processing and dehulling grain mechanically. Cleaning and dehulling were also noted to be safer as these methods are unlikely to produce other toxins that would be harmful to human health. Roasting also had some promising reductions in aflatoxins, up to an 85% reduction in B1 aflatoxin in one quoted study. While cooking reduced aflatoxins, it was noted that generally temperatures that are not achieved during home cooking (195 degrees Celsius for aflatoxin reduction) would be needed to sufficiently affect aflatoxin levels.

Other promising practices include: wet and dry milling, grain cleaning, canning, roasting, baking, frying, and extrusion cooking.18 Studies referenced in the USAID synthesis found that 23% of aflatoxin may be reduced by home preparation of a maize porridge. Caution however should be exercised, as even these reductions in aflatoxin levels may not bring the contaminants down to safe levels. More research needs to be done for specific recommendations in these practices and other practices including fermentation require further investigation.

Industrial processing: Industrial detoxification processes include using “inorganic salts and organic acids, and ammoniation which can eliminate the aflatoxin producing fungus with ammonia vapor [as well as] natural acids, salts and plant extracts. The USAID synthesis also notes that “though there is no widespread government acceptance of any decontamination treatment intended to reduce aflatoxin B1 levels in contaminated animal feeding stuffs. Ammoniation appears to have the most practical application for the decontamination of agricultural commodities.” In animal feed, an anti caking/binding agent like "hydrated sodium calcium aluminosilicate" may reduce AFM1 residues in milk, depending on the initial concentration of AFB1 in the feed (Figure 1).3

Figure 1 Aflatoxin and disease pathways in humans.31

Some countries have set permitted levels of aflatoxins in food in order to control and reduce detrimental effects of these toxins. These levels are variable and depend on economic and developing status of the countries.36 In US, Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has permitted a total amount of 20 ng/g in livestock feed and 0.5g/kg or 50 ng/l in milk.37 In European countries, permitted levels of aflatoxin M1 in milk, milk products and baby food are 0.005mg/kg.38 Also, different countries have set different regulations for permitted levels of aflatoxin in livestock feed. For instance, European Union (EU) has set permitted levels of aflatoxin from 0.05 to 0.5µg/kg. Factors such as weather conditions are also effective in determining permitted levels of aflatoxin. Permitted levels of this toxin in tropical countries are higher compared to mild and cold countries.39

In addition to financial losses and economic damage to agricultural and animal husbandry industries, losses due to aflatoxin contamination of foods include major pharmaceutical and health costs to treat food poisoning. Based on Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) reports, annually, about 20% of the foods produced in the world are contaminated by mycotoxins; in which aflatoxins have a greater share than the others. Prevalence of cancer and livestock disease in farms, weakening of livestock immune system, reduction in milk production and productivity are a few examples of damages to food and livestock industry. Considering huge economic losses and public health protection, prevention and neutralization of the toxins in livestock feed and food products of animal origin such as milk is essential.40,41

Aflatoxin B1 present at livestock feed causes different problems in genital, digestive and respiratory tracts through different mechanisms such as interference in metabolism of carbohydrates, fats and nucleic acids. Effects of aflatoxin B1 on livestock vary with concentration and time duration of contact with the toxin, strain and feed. High concentrations of this toxin are lethal, medial concentrations lead to chronic poisoning and continuous exposure to low concentration can result in hepatic cancer.42 Since about one fifteenth of consumed aflatoxin B1 is introduced into milk as aflatoxin M1 and different heat treatments used in preparing various dairy products cannot reduce quantity of aflatoxin M1, there is always a probability of poisoning by this toxin when consuming infected milk. Tumor genesis and mutagenesis capability of aflatoxin M1 is less than aflatoxin B1.38

Raising public awareness and disseminating currently available practices and technologies to growers, processors, and traders is essential for mitigation of aflatoxin contamination. As demonstrated in the studies above, many of the viable prevention solutions currently exist within the GAP, GMP and SPS recommendations. Finding ways to disseminate a complete package of technologies, equipment and knowledge to growers, while raising consumer demand for safe, high quality foods, will be essential elements of any action plan.

Aflatoxin risk communication however remains highly sensitive given that presenting the dangers without viable solutions is counterproductive. Withdrawing contaminated crops without alternative uses and compensation may heighten economic losses and affect food security among the poor.

Milk contaminated with aflatoxins is produced mostly from use of infected feed. Therefore, reducing aflatoxin contamination indirectly via control of livestock feed hygiene is possible. To achieve the aim, principles and health considerations during farming and crop production in farms and livestock feed factories, storage of livestock feed in traditional and industrial warehouses is necessary.43 Livestock feed is mostly include corn, cotton seed and canola, dietary supplements, wheat bran, dried bread, fat powder and alfalfa. Given that a significant percentage of the feed composition is derived from crops, health consideration during planting insects and, harvesting and storage of crops are factors affecting grain quality. Drought, rainfall, infection by insects and high moisture during flowering can be referred as major causes of aflatoxin occurrence in farms.

Adherence to appropriate irrigation programs, planting varieties resistant to moisture and molds weed control, insecticides application, harvesting at appropriate time, crop rotation in order to reduce the risk of pathogen, transfer from current farming year to the next year and fertilizing soil are useful ways of preventing pre-harvest aflatoxin infection. In addition, appropriate storage of crops which includes placing crops on clean and dry surfaces, protecting crops from moisture, heat, insects and use of fungicides are effective ways of reducing the infecti.31 another important way of controlling and reducing aflatoxin infection is adherence of hygienic condition in factories and livestock feed warehouses both in traditional and industrial levels are.

Controlling mold growth and aflatoxin formation in traditional farms and warehouses is highly important. In this regard, several studies have been carried out on quality of livestock feed and the amount of aflatoxin in feed produced milk. For example, it has been shown that the amount of aflatoxin in milk produced in.38 autumn and winter is higher compared to spring and summer. This is because in cold seasons,44 Feeding livestock on fresh forages is not possible due to unfavorable weather conditions and farmers have to use stored forages. Regarding that warehouse improper temperature and moisture conditions favor mold growth; therefore, it is necessary to improve storage conditions of livestock feed.44 Findings in some countries have shown that meeting safety conditions of livestock feed has led to decrease aflatoxin infection.9

According to Bovo et al.,45 toxin absorbents, chemical and biological methods are used directly for reducing aflatoxin in milk). Use of toxin absorbents is one of the main methods to reduce aflatoxin amount in milk. Absorbent soils such as bentonite, vermiculite, hydrated sodium calcium aluminosilicate (HSCAS) and active carbon are known as absorbent compounds for absorbing various toxins in aqueous environments. For instance, bentonite has been known as an effective reducer of aflatoxin M1 in infected milk. Binding capacity and stability of compound formed between absorbent and toxin are highly variable and influenced by temperature and pH. Information about the effect of absorbents on milk constituents is scarce; however, it has been shown that these substances have slight effect on nutritional quality of milk.37 In a study, effect of bentonite on milk protein content was not considerable and maximum reduction in protein content was only 5%. It should be mentioned that with respect to acceptability of absorbents as healthy additives by international authorities and ability to separate them from milk after absorption of aflatoxin, further investigations are in progress.

Aflatoxicos is can only be prevented by feeding rations free of aflatoxin. Preventing aflatoxin contamination requires an on-going and thorough sampling and testing program.

Aflatoxin is a type of mycotoxin produced by Aspergillus mold. Aflatoxin is the most well known and researched mycotoxin. Ethiopia is most favorable for aflatoxicogenic fungi and aflatoxin contamination, especially AFB1. Reports show that maize and groundnut are the most contaminated commodities in the country. These two commodities are most important in day to day dietary sources of the people in most regions of Ethiopia. The level of contamination for most commodities in the country is also very much greater than the international standard. Similarly milk and milk products are also contaminated with AFM1 above the standard level.

There are basically six groups of aflatoxins, AFB1, AFB2, AFG1, AFG2, AFM1 and AFM2; from which AFB1 are the most potent aflatoxins to cause health damage to human and animal. AFB1 is the most the most common contaminant of most Ethiopian commodities. Aflatoxins are toxic to human and animal and cause different diseases. There are two main ways people are usually exposed to aflatoxin. The first is when someone takes in a high amount of aflatoxins in a very short time. This can cause liver damage, liver cancer, mental impairment, abdominal pain, vomiting, death and others. The other way people suffer aflatoxin poisoning is by taking in small amounts of aflatoxins at a time, but over a long period. This may be happen if a person diet contain small amount of aflatoxin, as a result it may cause growth and development impairment, liver cancer, DNA and RNA mutation and others

The effect of aflatoxin on human depends on age, gender, level of exposure, duration of exposure, health condition, and strength of their immune system, diet and environmental factors. In Ethiopia and many other developing countries, aflatoxin cause huge health effect and economic loss. Commodities can be contaminated with aflatoxicogenic fungi and aflatoxin at any time, before harvest and after harvest. The prevention of aflatoxin once occurs and treatment of aflatoxicosis is difficult. However, there are some mitigation mechanisms pre- and post harvest, especially proper storage is essential with proper moisture and temperature. Moreover, awareness creation on aflatoxin contamination, its effect and management is essential.

Author declares no acknowledgment.

Author declares no conflict of interest.

©2018 Negash. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.