Journal of

eISSN: 2373-4310

Research Article Volume 1 Issue 3

1Department of Pulmonary Medicine, King George Medical University, India

2Department of Nutrition, IT College, India

Correspondence: Barkha Gupta, Department of Pulmonary Medicine, King George Medical University, Lucknow 226001, Uttar Pradesh, India, Tel +91-8884646464

Received: May 13, 2014 | Published: June 16, 2014

Citation: Gupta B, Kant S, Mishra R. Effect of nutrition education intervention on symptomatic markers of Indian patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Nutr Health Food Eng. 2014;1(3):105-114. DOI: 10.15406/jnhfe.2014.01.00016

Objective: To assess the effect of Nutrition Education intervention on HRQoL in Indian COPD patients.

Methods: Randomized control study conducted in 200 medically managed COPD patients - into Experimental group (100) and a non experimental group (100). Baseline evaluation included pulmonary function, HRQoL, and nutritional assessment. Nutritional intervention implied achieving dietary change through a combination of diet counselling and nutrition education through teaching aids. Final assessment was done at the end of 6month for all the parameters done at baseline.

Results: The overall retention for subjects was 73.4% at the end of study. The SF-36 showed significant improvements in domains SF, RE, MH and health change. The domains BP, GH, PF and RP did not change. There was a statistically significant change in the SGRQ for Impact domain only and no change in the Symptom and Activity domain.

Conclusion: In terms of symptomatic markers, nutrition intervention had significantly better scores on especially the psychological scales of SGRQ and SF-36. Physical impairment on all the outcomes markers did not show any change.

Practice implications: Because most of the patients with COPD are irreversible, nutrition interventions should be directed towards improving the quality of life through strategies of nutrition counselling activities.

Keywords: COPD, HRQOL, nutrition, lung function, education

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a major cause of health care burden worldwide and the only leading cause of death that is increasing in prevalence.1 Globally, COPD by 2020, is expected to rise to the 3rd position as a cause of death and at 5th position as the cause of loss of Disability Adjusted Lifeyears (DALYs). Although most of the available data on the disease are reported from the Western world, it is being equally recognized from Asia and Africa. The largest increase in the tobacco related mortality is estimated to occur in India, China and other Asian countries.2 COPD hitherto under diagnosed in India, is now recognized in 4-10 per cent of adult male population of India and several other Asian countries.3

Many aspects of COPD can only be accessed through patients reporting symptoms which are called as Sympatomatic markers.4 Some of these markers include, the straightforward recording of symptoms such as cough, wheeze, breathlessness and sputum colour. Others inlcude few questionnaires which has been developed for measuring impaired health in COPD. The are called as Health Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) questionnaires.5 Theoretically, HRQoL incorporates several dimensions experienced by the patient, that are affected by disease and health. This includes symptoms, physical function, cognitive performance, psychosocial condition, emotional status, and adaptation to disease.6 Though the severity of disease is an important determinant of the patient’s health, patient perception and adaptation largely defines the overall quality of life.7 Furthermore, it is generally agreed that improving the health of subjects is an important goal of therapeutic intervention for COPD.8

Nutritional status is a significant consideration for COPD patients and eating a nutritionally adequate diet is of immense importance to improve their quality of life. Both dietary counselling and nutritional supplementation are considered to improve the quality of life of COPD patients.9 Previously conducted nutritional intervention studies in COPD patients, were pointed towards oral supplementation in order to improve habitual dietary intake to help COPD patients and stop or reverse their weight loss.10 However, this focus is relatively recent, since weight loss was long regarded as inevitable for severe COPD patients. Nevertheless, nutritional support for severely underweight COPD patients may have only a very limited effect on the recovery of functional exercise abilities, because compliance (i.e. truly increased energy intake) appears to be difficult.11 Efficacy of dietary management might be improved by combining medically prescribed nutritional supplementation with a more behavioral approach aimed at long term changes in eating behavior and dietary intake.12 Few studies have been published on the possibilities and effects of voluntary dietary change among out-patients.13 Diet is often part of the focus in self-help or rehabilitation programmes for COPD patients and some of these programmes have been effective in improving the quality of life.14

To author’s present knowledge, there is a single Randomised Controlled Trial (RCT) conducted so far, that evaluates the specific impact of dietary counselling in outpatient COPD subjects on the HRQoL.9 However, several studies evaluating the effect of dietary counseling on energy intake and weight change have been done in other disease group outpatients.15,16 There is dearth of India specific data, regarding the assessment of nutritional status or role of nutrition intervention in stable COPD patients. None of the Indian studies, so far, have evaluated the effects of dietary counselling on patient-centre outcomes including quality of life, that are objective and subjective measures of functional status.

It can be inferred from these evidences, that it is not known whether nutrition education intervention in stable COPD patients has any effect on health status and HRQoL. It is also not clear, whether it effects the patient’s overall health status including physical, mental, social and employment status on standardized measurement tools, before and after 6month period. Therefore, the aim of the study was to investigate and assess the effect of nutrition counselling on perceived HRQoL in Indian stable COPD outpatients.

Patient sample

Diagnosed cases of COPD confirmed by spirometery, according to Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) 2006 guidelines, aged between 40-75years and having documented functional limitations, irrespective of sex, religion, caste, socio-economic status, present smoking status and nationality were included in the present. Accepting the type I error is equal to 0.05% and expecting absolute precision is equal to 5% with a power of (1-β) 80%, a sample size of 200 patients was calculated. This also includes additional subjects expecting 20% of them to be drop outs during the study period. Inclusion criteria was - patient should be in stable condition (defined as at least onemonth since the most recent hospitalization), FEV1/FVC ratio of less than 70% at initial evaluation, compliant to medical treatment, with sufficient language and intellectual capabilities to fill in the questionnaire and literate enough to read the education aids. Exclusion criteria were - patients with associated medical condition that could impair level of activity or worsen quality of life (cardiovascular disease or arthritic disorder).

Ethical consideration: The whole protocol was reviewed by Institutional Ethics Committee. The patients were provided with both verbal and written information about the whole study and related procedures. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient willing to participate in the study.

Study design

This was Randomized control and descriptive study, conducted in stable, medically managed COPD patients, randomised into two categories: Experimental (100) and a non-experimental group (100). At baseline, the experimental group received reinforced nutrition education package incentives and individualized dietary counselling by the dietician to improve nutritional status along with Standard Medical Treatment (SMT), as per GOLD Guidelines.17 The non-experimental received SMT only. However, they received written guidelines to increase energy and protein intake in their diet, as a part of usual treatment care but no individualized counselling was given. Both the groups received the same testing and follow up protocol. Nutritional status, Pulmonary Function Test (PFT) and HRQoL measures were monitored over sixmonth study period.

Randomization: Randomization was done a week before the start of the intervention. Subjects were randomized into two groups with the help of computer generated random numbers.

Study procedures

Both the study group filled the pre-tested assessment questionnaire that included information about general and demographic details of the study. The whole study was divided into three phases - baseline assessment, nutrition education impartation and facilitation to experimental group and SMT to the non-experimental group. The third phase - final assessment was done for all the parameters measured at baseline.

Baseline assessment: Both the study groups were evaluated for pulmonary function, functional exercise capacity, HRQoL, along with nutritional assessment that includes dietary and food intake at baseline by various standardized tools. PFT- Forced expiratory volume in one sec. (FEV1) and Forced Vital Capacity (FVC) was calculated from the flow volume curve measured by routine spirometry (PK Morgan’s Spiro 232), following accepted standards.18 6 Minute walk test (6MWT) was performed to measure the functional exercise capacity, as per ATS 2002, Standards.19 The overall nutritional assessment included anthropometric measurements, dietary and food intake calculations. To eliminate the Inter-examiner error, only one person took all the anthropometric measurements. All the patients were assessed for Height, Weight, Body Mass Index, Triceps Skinfold Thickness (TSF), Mid Upper Arm Circumference (MUAC) and Mid- upper Arm Muscle Area (MAMA). Standard protocol for anthropometric measurement was followed given by National Centre for Health Statistics.20,21 Measurements were taken 3times consecutively and mean values were observed. Measurements as body weight were compared with standards recommended by World Health Organization.22 TSF and MUAC were used to calculate the MAMC and MAMA using the equations by Gibson.23 Values obtained from MAMC and MAMA were compared to age and sex specific percentiles distributions developed from data collected during the Nutrition Canada Survey, 1981 since no Indian standards exist for comparability. Dietary recall of a typical day’s intake and a food frequency questionnaire were used to collect qualitative, descriptive information about usual food consumption patterns.

Nutrition education intervention: Nutritional intervention in the study was imparted through a combination of diet counselling and nutrition education along with facilitation through various teaching aids. The experimental group was provided with individually tailored nutrition intervention through diet charts. This was the implication of dietary modification or dietary restriction according to their individual requirements. Patients were advised to choose foods that would provide a diet that met their nutritional requirements without increasing portion sizes. Advice was tailored to take into account, each subject’s lifestyle, eating habits, symptoms, likes and dislikes and any religious or ethical restrictions. Nutrition education aids such as pamphlets, 23 page booklet, posters etc. were used as supportive means of enhancing knowledge and attitude along with the alteration in the dietary habits of the experimental group. The teaching aids used for impartation of nutrition were validated and tested for reliability before providing it to the patients.

The minimum contact with the dietician (researcher) in the intervention group was set to be four consultations during the study period - at baseline, at onemonth, threemonths and study end. The patients were offered to contact the dietician for dietary consultation whenever they felt a need for that. At baseline, the dietician (researcher) spent 30-45minutes providing advice. During each follow up visit, the dietician spent 15-20minutes reviewing recent dietary changes and discussing alternative strategies for intervention, wherever required. The visit follow up for the subjects in both the groups was done at 3rdmonth while by telephone at 4th and 5thmonths.

Final assessment: Final assessment was done at the end of 6month, which was also the last visit for all the parameters done at baseline.

Outcome measures: Outcome assessment was conducted at 1, 3 and 6months after baseline. Questionnaires, both - general health and disease specific, were used to assess the HRQoL. The St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire, SGRQ20,21 provided an assessment of respiratory health status while SF-3622 was used to assess the general health status. The questionnaires used in the study were translated and validated in local language (Hindi).

Statistical analysis

Primary data analysis was done to check and clean the data. Descriptive summary statistics, (such as means and proportions, along with respective standard deviations) was reported for the overall sample in text and tables. The statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS, version 12.0 & 16.0) software. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Independent t-test was used to assess the difference between the two study groups at baseline, whereas paired t-test was used to see the difference after period of 6months, from baseline values. One way ANOVA was used to observe the differences and compare means of experimental, non-experimental groups and normal values for SF-36 questionnaire. Post hoc test was used to observe the differences between means, over 6months in the two groups.

Preliminary characteristic of subjects at baseline

Table 1 shows the preliminary characteristic of subjects at baseline. With reference to age, sex, severity of COPD, pulmonary function and anthropometry, no statistically significant difference was observed between the two groups, except smoking index and packyears, which was higher in non-experimental group than the experimental group.

Adherence to intervention

Figure 1 shows the flow of participants throughout the study period. The overall retention for the study subjects was 73.4% (147 of 200) at the end of the study. The retention did not differ among groups (P=0.39).

Change in the lung function parameters

Change in the pulmonary function parameters after 6months of intervention period, is shown in Table 2. No significant difference was found between the two groups regarding the change in FVC Pre (p=0.81), FEV1 Pre (0.69) and FEV1/FVC % (Pre) (p=0.27) over 6months intervention period.

Changes in nutritional parameters

There was no significant difference in body weight (p=0.10), BMI (p=0.97), TSF (p=0.47), MAMC (p=0.40), MUAC (p=0.60) or AMA (p=0.21) between the two groups over time. Also, there was no significant interaction observed for any of these variables (Table 2).

Comparison of SF-36 of COPD subjects with Healthy adults

Table 3 shows the base line scores of various domains of SF-36 questionnaire, when compared between experimental group and non-experimental group showed no significant difference.

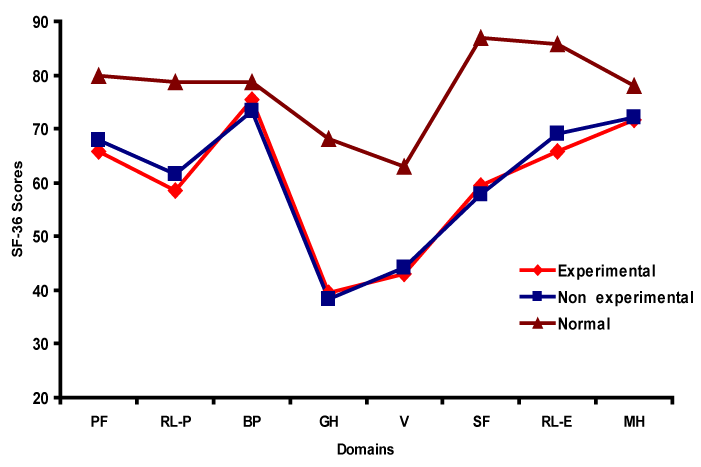

Figure 2 illustrates the SF-36 subscales as measured at baseline in both study group COPD subjects compared to published values for healthy adults.23 It was observed that six of the eight subscales {Physical Functioning (PF), Role limitation -Physical (RP), General Health (GH), Vitality, energy and fatigue (VT), Social Functioning (SF), Role limitation –Emotional (RE)} were significantly lower in COPD patients than in healthy individuals. The domains Bodily Pain (BP) and Mental Health (MH) for the study groups were similar to the values published for healthy adults.24

Change in general health status SF-36

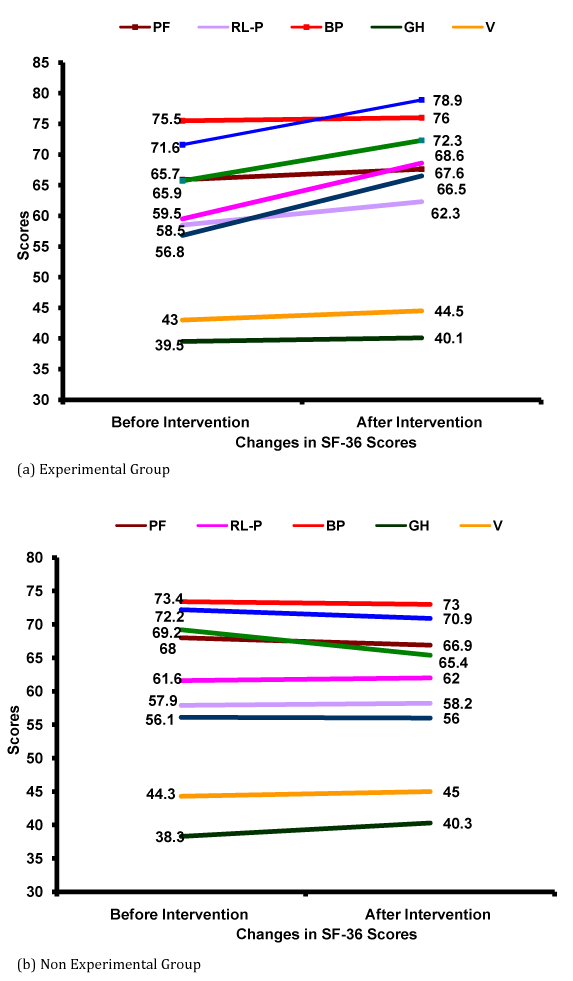

No significant differences were observed between the two groups with reference to general health as assessed by SF-36 questionnaire in not all but some of the domains over the sixmonths intervention period (Figure 3).

The SF-36 showed significant improvements in SF (∆ mean difference: 9.1±7.6; p=0.01), RE (∆ mean difference: 6.6±5.3; p=0.04), MH (∆ mean difference: 7.3±3.5; p=0.02) and health change (∆ mean difference: 9.7±2.5; p=0.01) domains of the questionnaire for experimental group when compared non experimental group, following nutrition education intervention (Table 4).

The SF-36 scores of BP (∆ mean difference 0.5±1.5; p=0.10), GH (∆ mean difference 0.6±0.9; p=0.79), PF (∆ mean difference 1.7±1.3; p=0.90) and RP (∆ mean difference 3.8±1.8; p=0.32) in experimental group, showed no significant changes after nutrition education intervention, when compared to non-experimental group [BP ∆ mean difference 0.4±0.8), GH (∆ mean difference 2.0±5.4), PF (∆ mean difference - 1.1±5.1) and RP (∆ mean difference 0.4±4.9).

Changes in SGRQ

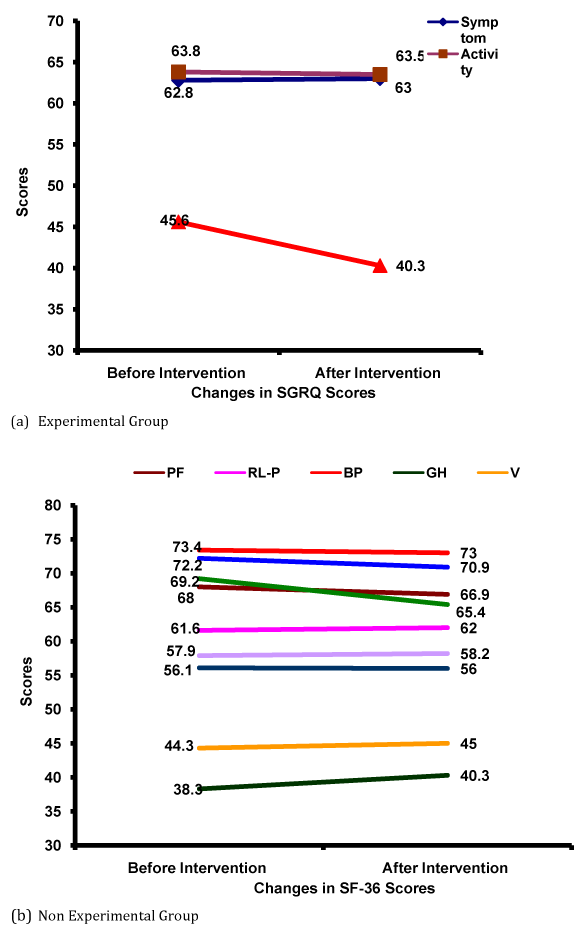

As a result of nutrition education intervention, with respect to SGRQ scores, it was observed that only psychological wellbeing i.e. impact domain has improved in experimental group compared to non-experimental group (Table 5) (Figure 4). There was statistically no significant change in the SGRQ domains for Symptom (∆ mean difference 0.2±5.6) and Activity (∆ mean difference - 0.3±2.5) in the experimental group from baseline to the end of the study when compared to same domains [Symptom (∆ mean difference 0.5±2.2; p=0.56) and Activity (∆ mean difference 1.3±11.1; p=0.98)] in non-experimental group after 6months intervention period. There was a statistically significant change in the SGRQ for Impact domain (∆ mean difference - 5.3±1.8) from baseline to the end of the study between the groups.

Figure 2 Comparison of SF-36 Subscales in COPD subjects (Experimental and Non experimental group) and healthy adults.

Figure 3 Changes in health related quality of life (HRQOL) scores of subjects after nutrition intervention education general health status-SF 36.

Figure 4 Changes in health related quality of life (HRQoL) scores of subjects after nutrition intervention education disease specific SGRQ.

Preliminary characteristics |

Experimental group |

Non experimental group |

p-value |

Total number of subjects (%) |

100 |

100 |

|

Males |

66 (66) |

70 (70) |

0.51 |

Females |

34 (34) |

30 (30) |

0.50 |

Mean age in years# |

58.71±9.86 |

56.75±10.36 |

0.52 |

Males |

56.34±9.82 |

54.85±8.37 |

0.97 |

Females |

55.52±9.31 |

55.18±9.89 |

0.62 |

Severity of COPD N(%) |

|||

Mild (I) |

5 (5) |

3 (3) |

0.45 |

Moderate (II) |

43 (43) |

46 (46) |

|

Severe (III) |

50 (50) |

49 (49) |

|

Very Severe (IV) |

2 (2) |

2 (2) |

|

Smoking history |

|||

For males only |

n=66 |

n=70 |

- |

Ex smokers |

34 (51) |

35 (50) |

0.27 |

Current smokers |

26 (40) |

32 (46) |

|

Non smokers |

6 (09) |

3 (04) |

|

Smoking Index# |

361.3±39.1 |

402±56.23 |

0.02* |

Pack years# |

7.85±5.03 |

12.90±3.82 |

0.01* |

Domestic exposure |

|||

For females only |

n=34 |

n=30 |

- |

Presence |

26 (76) |

22 (72) |

- |

Number of hrs/day# |

3.11±0.23 |

3.31±0.71 |

0.11 |

Number of years# |

24.59±4.81 |

27.12±5.33 |

0.86 |

Table 1 Preliminary characteristics of study subjects at baseline

P-Values not significant (5% level of significance) for any of the parameters

#Values presented as Mean±SD

*Values significant (5% level of significance)

Pulmonary function |

Experimental group |

Non-experimental group |

p-value |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Baseline (n=100) |

Final |

∆ Change in the values |

Baseline (n=100) |

Final |

∆ Change in the values |

||

Lung function parameters |

|||||||

FVC (Pre) (lit.) |

2.02±0.61 |

1.89 ±0.49 |

- 0.12±0.43 |

1.89±0.60 |

1.79±0.73 |

- 0.09±0.38 |

0.81 |

FVC (Post) (lit.) |

2.20±0.59 |

2.13±0.46 |

- 0.07±0.30 |

2.10±0.68 |

2.07±0.66 |

- 0.03±0.41 |

0.80 |

FEV1 (Pred.) (lit.) |

51.92±16.92 |

52.14±15.99 |

0.21±10.69 |

45.5±16.63 |

43.58±16.74 |

- 1.91±4.52 |

0.73 |

FEV1 (Pre) (lit.) |

1.06±0.47 |

0.95±0.45 |

- 0.03±0.22 |

0.92±0.39 |

0.89±0.48 |

- 0.03±0.22 |

0.69 |

FEV1 (Post) (lit.) |

1.13±0.38 |

1.17± 0.42 |

- 0.06±0.13 |

1.03±0.42 |

0.96±0.42 |

- 0.06±0.13 |

0.66 |

FEV1/FVC% (Pre) |

51.71±10.78 |

52.21±22.87 |

2.5±9.12 |

48.75±8.98 |

48.21±9.70 |

- 0.53±3.82 |

0.27 |

Nutritional parameters |

|||||||

Weight |

50.0±9.2 |

54.1±11.8 |

4.1±2.6 |

49.6± 6.8 |

49.3± 8.1 |

-0.3± 1.3 |

0.10 |

Body Mass Index(kg/m2) |

20.2±2.5 |

21.5±3.5 |

1.3±1.0 |

19.3±3.1 |

19.4±4.0 |

0.1±0.9 |

0.97 |

TSF (cm) |

6.5±3.0 |

6.9±2.2 |

0.4±0.8 |

6.8±0.9 |

6.5±1.2 |

- 0.3±0.3 |

0.47 |

MUAC (cm) |

21.1±2.3 |

21.5±2.5 |

-0.4±0.2 |

21.0±2.5 |

21.4±3.1 |

0.4±0.6 |

0.60 |

MAMC (cm) |

18.9±4.7 |

19.1±4.7 |

0.2±0.0 |

19.8±3.1 |

19.5±2.9 |

- 0.3±0.2 |

0.40 |

AMA (cm2) |

31.2±2.3 |

31.8±1.9 |

0.6±0.4 |

31.5±2.7 |

30.0±2.8 |

- 1.5±0.1 |

0.21 |

Table 2 Change in the lung function parameters and nutritional parameters after Nutrition education intervention

All values presented as Mean±SD

P values not significant (>0.05) for any of the parameters

FEV1 (Pre)=Forced expiratory volume in one second before bronchodilator;

FEV1 (Post)= Forced expiratory volume in one second after bronchodilator;

% predicted=expressed as percentage of the predicted value; FVC = Forced Vital Capacity; FEV/ FVC (%)=FEV1 expressed as % of inspiratory vital capacity

TSF, total skin fold thickness; MUAC, mid upper arm circumference; MAMC, mid arm muscle circumference AMA, mid upper arm muscle area

General health status SF-36 |

Experimental group |

Non experimental group |

Normative values |

|---|---|---|---|

(n=100) |

(n=100) |

||

Physical functioning |

65.9±15.9 |

68.0±11.8 |

80.0 |

Role limitation physical |

58.5±12.1 |

61.6±9.4 |

78.8 |

Bodily pain |

75.5±14.5 |

73.4±13.8 |

78.8 |

General Health |

39.5±13.7 |

38.3±15.4 |

68.1 |

Vitality, energy & fatigue |

43.0±16.3 |

44.3±10.2 |

62.9 |

Social functioning |

59.5±14.7 |

57.9±13.3 |

86.9 |

Role limitation emotional |

65.7±16.0 |

69.2±12.8 |

85.8 |

Mental Health |

71.6±12.7 |

72.23±20.3 |

78.0 |

Table 3 Pre assessment of general health status-sf-36 in experimental and non experimental group

All values presented as Mean±SD

Higher scores represent better HRQoL

Experimental group |

Non-experimental group |

p-value |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Baseline |

Final |

∆ Change in the values |

Baseline |

Final |

∆ Change in the values |

||

Physical functioning |

65.9±15.9 |

67.6±14.6 |

1.7±1.3 |

68.0±11.8 |

66.9±9.3 |

- 1.1±5.1 |

0.90ns |

Role limitation physical |

58.5±12.1 |

62.3±10.3 |

3.8±1.8 |

61.6±9.4 |

62.0±4.5 |

0.4±4.9 |

0.32ns |

Bodily pain |

75.5±14.5 |

76.0±12.0 |

0.5±1.5 |

73.4±13.8 |

73.0±13.0 |

0.4±0.8 |

0.10ns |

General Health |

39.5±13.7 |

40.1±12.8 |

0.6±0.9 |

38.3±15.4 |

40.3±10.0 |

2.0±5.4 |

0.79ns |

Vitality, energy & fatigue |

43.0±16.3 |

44.5±10.4 |

1.5±5.9 |

44.3±10.2 |

45.0±11.2 |

0.7±1.2 |

0.06ns |

Social functioning |

59.5±14.7 |

68.6±22.3 |

9.1±7.6 |

57.9±13.3 |

58.2±12.3 |

0.3±1.0 |

0.00* |

Role limitation emotional |

65.7±16.0 |

72.3±21.3 |

6.6±5.3 |

69.2±12.8 |

65.4±13.9 |

- 3.8±1.1 |

0.04* |

Mental Health |

71.6±12.7 |

78.9±16.2 |

7.3±3.5 |

72.2±20.3 |

70.9±15.6 |

- 1.3±4.4 |

0.02* |

Health change |

56.8±21.4 |

66.5±18.9 |

9.7±2.5 |

56.1±17.4 |

57.2±12.3 |

1.1±5.1 |

0.00* |

Table 4 Changes in health related quality of life (HRQoL) scores of subjects after nutrition intervention education

General Health Status-SF 36

All values presented as Mean±SD

Higher scores represent better HRQoL

Ns=not significant

*Values significant at 5% level of significance

Experimental group |

Non-experimental group |

p-value |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Baseline |

Final |

∆ Change in the values |

Baseline |

Final |

∆ Change in the values |

||

Symptom |

62.8±12.5 |

63.0±18.1 |

0.2±5.6 |

60.5±12.0 |

61.0±14.2 |

0.5±2.2 |

0.56ns |

Activity |

63.8±22.5 |

63.5±20.0 |

- 0.3±2.5 |

63.2±22.7 |

64.5±11.6 |

1.3±11.1 |

0.98ns |

Impact |

45.6±11.1 |

40.3±9.3 |

- 5.3±1.8 |

49.9±13.6 |

52.0±11.6 |

2.1±2.0 |

0.01* |

Table 5 Changes in health related quality of life (HRQoL) scores of subjects after nutrition intervention education Disease Specific SGRQ

All values presented as Mean±SD

Higher scores on SGRQ represent worse HRQoL lower scores represent better HRQoL

ns=not significant

*Values significant at 5% level of significance

This is one of the first Indian RCT to evaluate the specific impact of dietary counselling on outcome in COPD patient group.

Literature review shows that there is only one RCT evaluating the specific impact of dietary counselling in outpatients with COPD9 and four in outpatients with other clinical conditions i.e. Crohn’s disease;15 Cancer;16 osteoporotic fractures25 and kidney disease26 that reported the effect of dietary counselling on both energy intake and weight change and, significant differences were observed between the groups in favor of intervention. In contrast to the current study, none of the Indian studies have evaluated the effects of dietary counselling on both nutritional outcomes and on patient-centered outcomes including quality of life which are objective and subjective measures of functional status.

Nutritional intervention studies previously done in COPD patients were mainly pointed towards oral supplementation in order to improve habitual dietary intake. Efficacy of dietary management might be improved by combining medically prescribed nutritional supplementation with a more behavioral approach aimed at long term changes in eating behavior and dietary intake. Therefore, this study was undertaken to identify the dietary and personal factors which contribute to failure of weight gain and failure to increase nutrient intake in malnourished COPD patients. As well, the effect of individual nutrition counselling on nutrient intake, body weight, respiratory function and perceived health related quality of life in these patients was assessed. Additionally the patient’s perception of nutrition education provided was evaluated.

In COPD patients, there is a common triad of dyspnoea, especially on exertion, intermittent cough and fatigue. This triad is major contributor to disability and quality of life in COPD patients is severely compromised.27 Individualized dietary intervention and nutrition counselling was not successful in sustaining adequate nutrient intake to promote significant weight gain and improvement in nutritional status in COPD patients. There were no significant differences in body weight, nutrient intake, respiratory function and functional exercise capacity in both the groups over time. Dyspnoea, fatigue, poor appetite, early satiety, and gastrointestinal discomfort appeared to be impediments in sustaining an adequate intake to promote to promote weight repletion. However, there was an improvement in not all but some of the domains of HRQoL in patients resulting from effect of nutrition education program. The findings of the study confirm that patients with COPD have significant decreases in HRQoL domains, and the latter deteriorates in parallel with lung function impairment.

The study found no significant pre and post intervention difference in respiratory function. More severe limitation may have made it more difficult to demonstrate the effectiveness of nutrition intervention. The results of the study are similar to the study done by Weekes et al.,9 who have failed to show any effect of dietary counseling and food fortification in COPD patients on the objective functional measures.

The study found no significant pre and post intervention difference in distance walked in six minutes that is used to assess functional exercise capacity. It should be noted that walking test performance also depends on various factors including motivation, endurance, respiratory function, cardiovascular fitness and neuromuscular function. It is not easy to enumerate the consequences that these aspects may have on the test results. Though, it is expected that these factors would affect the experimental and non-experimental group equally. The results that nutrition education intervention did not have any effect on objective measures of respiratory function concur with those reported in a Cochrane Review28 where nutritional support had no significant effect on lung function or respiratory muscle strength in patients with stable COPD. The majority of patients in the current study were sedentary and effectively housebound. In the absence of an increase in physical activity, improvements in muscle strength and function are unlikely to result from nutritional intervention alone.

The study found no significant pre and post intervention difference in distance walked in six minutes that is used to assess functional exercise capacity. It should be noted that walking test performance also depends on various factors including motivation, endurance, respiratory function, cardiovascular fitness and neuromuscular function. It is not easy to enumerate the consequences that these aspects may have on the test results. Though, it is expected that these factors would affect the experimental and non-experimental group equally. The results that nutrition education intervention did not have any effect on objective measures of respiratory function concur with those reported in a Cochrane Review28 where nutritional support had no significant effect on lung function or respiratory muscle strength in patients with stable COPD. The majority of patients in the current study were sedentary and effectively housebound. In the absence of an increase in physical activity, improvements in muscle strength and function are unlikely to result from nutritional intervention alone.

The study’s finding of no significant differences in pulmonary function over time along with body weight change are in consistent with that of other studies. Re-feeding studies in malnourished COPD patients where little or no weight gain occurred also did not document significant change in respiratory function.29 Only studies which reported significant weight gain and improvement in nutritional status were able to document significant improvement in respiratory muscle performances along with significant weight gain. Wilson et al.,30 reported 41% increase in respiratory muscle performances. However these studies have very smaller sample size (n=6) and there was no control group.

The findings of no significant difference over time or between groups in anthropometric measures are in coherent with no statistically significant difference over time or between groups in nutrient intake. These subjects had encountered obstacles to sustaining an increased nutrient intake over the study period. The findings of the current study are contradictory to that of done by Weekes et al.,9 who have achieved significant weight gain as a result of nutrition intervention. However, they have also provided oral nutritional supplements as food fortification along with dietary counseling to their subjects.

Nutritional depletion has been shown to be associated with adverse effects on health status. A neutral-quality cohort study31 evaluated the effects of body weight on both generic and disease-specific HRQoL in patients with COPD. The underweight group (UW) had greater impairment in HRQoL scores than the normal weight (NW) group. Short Form-36 is a generic tool and was used in the study since more global issues related to quality of life can be assessed such as social role, mental health and general well being. Also it has been shown to be sensitive and promising to measure quality of life for general population, including elderly patients. SGRQ is a standardized, questionnaire for measuring impaired health and perceived HRQoL in obstructive airways disease. In the present study, the scores of Symptoms and Activity domains of SGRQ were higher than that of original version of SGRQ. The ‘Impact’ domain was not as affected and still lower when compared to the original ones. This represents that the study subjects in this study were more physically impaired and faced problems in carrying out their everyday activities. Nevertheless, this difference could be attributed to the cultural and ethnic differences in responding to the question. However the scores of these domains are somewhat same as scored of Indian population of COPD in a study done in Indian population.32 The SF-36 showed significant improvements in social function, emotional role, mental health and health change following nutrition education intervention, although the scores remained below than those of healthy adults. This suggests that the subjects perceived an improvement from their mind set though were unable to work it out due to physical impairment placed by the disease. However the subjects were unable to assess the impact of nutrition education intervention on their social function. The SF-36 scores of, pain, general health, physical function and physical role limitation were not significantly changed after nutrition education intervention. Bodily pain was almost similar in the COPD subjects to the general population and would not be expected to change since it is not the focus of intervention. Similarly, since nutrition education intervention does not affect the underlying COPD, it is not unexpected that the subject’s perception of his or her health would change. Considering SGRQ, it was observed that only the domains associated with psychological well being i.e. impact domain has improved in experimental group as a result of nutrition education intervention. The stability of the experimental group’s psychological well being may be a reflection of the psychosocial benefit that they obtained from receiving individualized nutrition counselling. One goal of nutrition counselling was to emphasize the patient’s ability to problem-solve and to focus on strengths than the weakness. It has been documented that psychological well being is positively correlated with problem-focused coping strategies.33

Limitations of the study

Before drawing conclusions, several aspects of intervention, limitations, the study design and study population should be reviewed in the context of literature.

Study design: The intervention (nutrition education) in this study was less intensive as it consisted of a nutrition education teaching aids and an action plan only. No use of nutritional supplementation or exercise component was added. However, various studies involving the use of nutritional supplements also failed to show any statistically significant effect particularly on HRQoL or health status.

Selection bias: The patients in this study were well stabilized and had moderate-to-severe COPD. The study population was probably pre selected and the samples were co-operative, motivated and mentally alert individuals, as is in the case of all randomization studies. This group may have been more interested in diet or motivated to modify their diet than others. Also, a convenience sample that was educated enough and segregation of the patients with physical or cognitive problems prevented them from either filling the questionnaire or reading nutrition education aids. Though this type of pre selection might raise concerns about generalizability, but the validity of the study was not compromised. Because of the randomization, there is no reason to believe that there was any difference between experimental and non experimental group at baseline and ensured comparability.

Recall bias: Though most of the patients in the study were literate enough to fill the questionnaires, but still they were interacted when these questionnaires were administered by the researcher. This may have introduced recall bias due to patient’s response.

Short duration: The impact of any nutrition or health education programs may require a longer period to manifest itself (i.e. 6months follow up was too short). Nevertheless, experiences with other kind of education interventions (e.g. smoking cessation) suggests that impact decreases over time. It is also possible that the duration of intervention was too short and a greater time-period interval to active the desired outcomes. Lung associations that offer on-going education program meet regularly on a continuing basis and therefore provide repetition and reinforcement to the learning process.

Cultural taboos: It is very important to detect the patient’s current beliefs according to their cultural habitual intake, for providing information or supportive eating interventions. One of the concerns with providing education to several subjects was their suspicion regarding modification and alteration in their diet. Dietary counselling with COPD is not unusual but how and when the advice was provided, makes a difference. A nutrition education plan was prepared based on individual behavior; still it was difficult for the subjects to adapt these changes. This made hard while informing and convincing the patients and their caregivers of the importance such a diet which is contrary to beliefs.

However, it could also be argued that that the findings do not indicate that nutrition education program provided no benefits, but only that the measures were too crude to detect these benefits. The fact that almost 75% of the subjects entering the educational intervention program completed them suggests that the patients valued participation. Therefore, it is not that nutrition education programs do not provide benefit but only that they do not provide the same benefit as comprehensive rehabilitation program that includes exercise training, health education and psychosocial counselling.

In the present study, individualized counselling along with the provision of nutrition education teaching aids was not successful in promoting nutrient intake for weight gain and improvement in nutritional status. Consistent with other refeeding studies which were not able to achieve adequate intake to achieve weight gain, the present study also found no significant time or group effects on pulmonary function tests or functional exercise capacity as assessed by distance walked in six minutes. Despite not gaining weight, the patients perceived that the nutrition counselling was beneficial. Furthermore, dietary counselling resulted in significant benefits on not all but some of the domains of quality of life and subjective measures of functional status. In terms of symptomatic markers, nutrition intervention had significantly better scores on some of the domains especially the psychological scales of SGRQ and SF-36 than did the non experimental group. Physical impairment on all the outcomes markers did not show any changes.

Practice implications

Role of nutrition education in disease management is either not known to the patients and health professionals or not given due importance, because most of the patients with COPD are irreversible, interventions should be directed towards improving the quality of life through strategies of self care and education. There is a need for effective strategies to support the patients through nutrition counselling activities.

We are thankful to Indian Council of Medical Research Delhi (IRIS No. 2007/0990) for providing necessary funds for conducting the study.

I confirm all patient/personal identifiers have been removed or disguised so the patient/person(s) described are not identifiable and cannot be identified through the details of the story.

Author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

©2014 Gupta, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.