Journal of

eISSN: 2373-4310

Research Article Volume 8 Issue 2

1Food and Nutrition Administration, Ministry of Health, Kuwait

2Colleage of Basic Education, The Public Authority for Applied Education and Training, Kuwait

3Public Authority for Food and Nutrition, Kuwait

Correspondence: Maryam Aldwairji, Food and Nutrition Administration, Ministry of Health, Kuwait City, P. O Box 42432 Sulaibikhat 70655, State of Kuwait, Tel +965 2481 3848

Received: January 17, 2018 | Published: March 2, 2018

Citation: Dwairji MAA, Al-Qaoud NM, Husain WA, et al. Breakfast consumption habits and prevalence of overweight and obesity among Kuwaiti adolescents. J Nutr Health Food Eng. 2018;8(2):94-103. DOI: 10.15406/jnhfe.2018.08.00263

The aim of this study was to investigate the association between breakfast consumption and overweight and obesity from a gender perspective.

Design: A cross-sectional study using a structured questionnaire around breakfast consumption habits.

Setting: Participants were sampled from middle and high schools (aged between 12 and 18 years) as part of the ongoing Kuwait National Nutrition Surveillance (KNNS) System. Overweight and obesity were defined according to the WHO age- and sex-specific BMI cut-off points. Multiple regression analyses were conducted to examine the relationship between risk of overweight and obesity among those who consume breakfast < 5 vs. > 5 times a week.

Subjects: A multistage, stratified sample of 2,153 adolescents (boys and girls) was recruited, with a response rate of 92%. Body weight and height were measured.

Results: A significant inverse association of breakfast consumption and overweight and obesity was found among all adolescents, where the risk of being obese is 20% less likely to occur (OR = 0.80, 95% CI: 0.67– 0.96; P for trend = 0.02) among those who consume breakfast more than five times a week than in breakfast skippers, after an adjustment for potential confounders. In addition, analyses were carried out among boys and girls separately, in which the frequency of breakfast consumption was inversely associated with overweight and obesity among boys only.

Conclusion: A frequency of breakfast consumption less than five times a week is associated with a high risk of overweight and obesity among Kuwaiti adolescents (P = 0.02). In a country where obesity is the major health issue for children, it is important to investigate the possible risk factors responsible for overweight and obesity among Kuwaiti adolescents. This can help in identifying a target population for future intervention programs.

Keywords: breakfast, adolescence, obesity, eating habits, weight perception

KNNS, kuwait national nutrition surveillance; WHO, world health organization; BMI, body mass index; OR, odd ratio; KBOS, kuwait breakfast obesity study; SD, standard deviation; IQR, Interquartile range; CI, Confidence interval; K, Kappa

Breakfast is widely considered a key component of a healthy dietary lifestyle. However, the habit of skipping breakfast among children and adolescents is common.1,2 It has been demonstrated that daily consumption of breakfast is more frequent among boys (39–76%) than among girls (36–71%).,2 Regular breakfast consumption is generally associated with high dietary quality and nutrient profiles in children.3 A systematic review has shown that breakfast consumption is generally associated with positive effects on cognitive performance.4 In addition, a recent review has demonstrated the positive effects of breakfast consumption on cardiovascular health and weight management.5 Observational evidence has shown that children and adolescents who eat breakfast have a reduced risk of becoming overweight and obese, compared to breakfast skippers.6 However, some studies have found no such associations.7

Globally, obesity has more than doubled since 1980.8 The growing prevalence of overweight and obesity has been described as a pandemic in developing countries. 9,10 In 2015, the KNNS reported that overweight and obesity is on the rise among all age groups, with a prevalence of 57% at age 11 to < 13, 52.4% at age 13 to < 15, 51.6% at age 15 to < 17, and 47.9% at age 17 and above.11

There is a lack of information describing the relationship between breakfast consumption and obesity in Kuwait. Therefore, this cross-sectional study may be the first to nationally assess breakfast consumption among Kuwaiti adolescents on a large, homogenous scale. The aim of the current study is to investigate the association between breakfast consumption and overweight and obesity from a gender perspective.

The Kuwait Breakfast Obesity Study (KBOS) was a cross-sectional study conducted in 2015–2016. A sample of 2,219 Kuwaiti students aged between 12 and 18 years (1,142 girls and 1,077 boys) were selected from the KNNS, which used the sentinel multistage stratified random sampling technique from all six governorates in Kuwait to ensure that the target population was likely to be represented.12 The KNNS began in 1995 with assistance from the World Health Organization (WHO), which is responsible for equipping policy makers of the country’s Health Ministry with statistical data for policy formulation and evaluation of health interventions.12

In the present study, a structured questionnaire was distributed and filled out, following a standard protocol, under the supervision of trained dieticians, who checked for questionnaire completeness and explained clearly that there was no “right” or “wrong” response to questions. The questionnaire was designed based on a close-ended question format that explored breakfast consumption habits, students’ perceptions, and physical activity. Participants provided socio-demographic information in the questionnaire. Other questions in the KBOS questionnaire were adopted from literature of similar studies.13,14 The content of the questionnaire was determined by four experts in the field of nutrition, public health nutrition, and paediatrics, examined for clarity and appropriateness of the English language, and then translated to Arabic with the help of a language expert. During the developmental stage, the questionnaire was pre-tested with a small group, and the results of the pilot study were used to finalize the questionnaire. Consumption of breakfast was assessed in terms of the frequency of intake per week, as was done in other studies.15,16 An eight-response category was provided on a scale of 0–7 times per week. In this study, the terms “< 5 times a week” and “> 5 times a week” were used, as in a previous study.17 This variable was created because, by categorization, the differences in the number of cases and non-cases by frequency of breakfast consumption could easily be assessed and could limit the influence of possible outlying data. In addition, this helps to minimize the number of categories within the variable as there is always a concern in statistical analyses regarding loss of information with categorization.18

Other questions investigated food preferences from selected food groups. Students were asked about the frequency with which food was purchased from a canteen, possible reasons for skipping breakfast, and places where breakfast was consumed. They were also asked their opinion regarding the benefits of eating breakfast. Students were asked to select from any of the following, as reasons for not eating breakfast: “not hungry”, “insufficient time”, “dislikes food served”, “on a dietary regimen”, and “would not want to gain weight”. Meal frequency was assessed using the question: Do you consume all main meals regularly except breakfast? Possible answers included “never”, “once a week”, “twice a week”, “daily”, “only regular lunch” or “only regular dinner”).

Body weight perception was assessed using questions adopted from a previous study19 and participants choosing one of the following answers: “below normal weight”, “normal weight”, and “above normal weight”. The students were divided into BMI categories based on perceived weight and measured weight status. Weight status was categorized as underweight, normal weight, and overweight/obese. In addition, frequencies of participation in physical activities and sedentary behaviors, such as watching TV and playing electronic games, were explored.

Body height and weight were determined by standard anthropometric methods. Students’ heights were measured without shoes to the nearest 0.1 cm using a SECA model 220 electronic stadiometer. Students’ body weights were measured without shoes and in light clothing to the nearest 0.1 kg using a SECA 708 electronic weighing scale (SECA, Medical scales and measurement systems, Hamburg, Germany). Body mass index (BMI) was calculated using weight/height2 (kg/m2). The BMI z-scores (kg/m2) were obtained using the WHO Anthro Plus software, version 3.1, 2010.20 Age- and sex-specific cut-off points for BMI z-scores were used according to the WHO 2007 growth reference.21 BMI-for-age z-scores were chosen as follows:

Z-score > 1 for classifying “overweight”

Z-score > 2 for classifying “obesity”

Z-score < -2 and < -3 for classifying “thinness” and “severe thinness”, respectively

All statistical analyses were conducted using STATA statistical software version 12 (Corp-Stata, 2010).22 All data were checked and coded. Confidentiality of a participant’s identity was maintained throughout the analyses. All non-Kuwaiti students and those who were more than 18 years of age were excluded from the study (n = 2153).

The distribution of each variable of interest was checked for possible errors, such as a typing error. Continuous variables were checked using box plots and histograms for normality and any potential outliers. Descriptive statistics were reported as mean values ± SD for continuous data, if normally distributed, while median and interquartile range (IQR) was used for abnormally distributed data. Frequencies and percentages were used for categorical variables. An independent t-test and non-parametric test (Mann-Whitney Test) were chosen based on variable normality to assess the differences between genders, whereas the Chi-square test was used for categorical variables.

Logistic regression analyses were applied and results presented as odds ratios (ORs) and at 95% confidence intervals (CI) to predict the strength of the association between the risk of overweight/obesity and each of the other variables of interest.

Since only 58 students were labelled as underweight, the students were divided into two groups: the normal weight group (as a reference group) and the overweight and obese group.

In the current study confounders were identified from previous studies, an approach which is also referred to as a priori confounders.5 Statistical significance was established at P<0.05. Odd ratios were reported as unadjusted and were adjusted to potential confounders including age, gender, parental education and occupation, physical activity, snacking, and main meal frequency, as described in previous studies.5

Kappa statistics were computed to determine the extent of agreement between the students’ perceptions of their BMI categories and the BMI categories, calculated from measured weight and height, for the total gender-specific study population. Kappa (K) values ranged from between 0 to 1, where the value of 0 meant no agreement between the students’s perceived BMI and measured values, while the value of 1 meant a perfect agreement between the two. Specifically, this statistical approach helped to determine the similarity between students categorized into the perceived overweight/obese group and those categorized into the actual overweight/obese group in the KBOS. The interpretations of strength of the agreement for Kappa, as described by Landis and Koch (1977),23 were used.

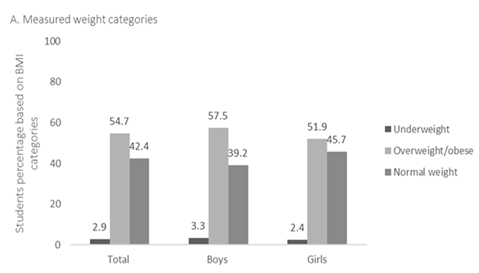

Demographic characteristics of the participants (n=2,153) according to gender are presented in Table 1. All students were aged between 12 and 18 years old with an average age of 15 years±1.9 for boys and girls. Boys were significantly heavier, with an average weight of 67.6 kg±24.6, than girls were (59.4 kg±16.5) (P<0.001). In addition, boys were taller, with an average height of 1.62m±0.11 than girls (1.56m±0.64) were (P<0.001). Thirty-nine percent of boys and 45.7% of girls were classified as normal weight, while 57.5% and 51.9% of boys and girls were classified as overweight and obese (P<0.001), respectively. No statistically significant differences were found for governorate, educational level, parent occupation, and presence of chronic diseases between boys and girls. Figure 1 shows that 39.5% of Kuwaiti adolescents consume breakfast daily. Of this percentage, 21.8% were boys while 17.7% were girls. Nearly 21.7% of the total number of participants consumed breakfast at least once a week or never. Of this, 13% were girls, while 8.7% were boys. There was a significant difference in the frequency of consumption of breakfast between boys and girls (P<0.001).

Variable1 |

Boys |

Girls |

P-value |

Age + SD |

15.1 + 1.87 |

15.1 + 1.87 |

0.91 |

Weight, Kg |

67.6 + 24.6 |

59.4+ 16.5 |

<0.001 |

Height, m |

1.62 + 0.11 |

1.56 + 0.64 |

<0.001 |

BMI z-score2 |

1.38 + 2.44 |

1.09 + 2.09 |

<0.001 |

BMI for age category3 |

|||

Within normal BMI range |

405 (39.2%) |

454 (45.7%) |

<0.001 |

Overweight / Obesity |

594 (57.5%) |

515 (51.9%) |

|

Below BMI range |

34 (3.3%) |

24 (2.4%) |

|

Governorates3 |

|||

Capital |

181 (17.1%) |

215 (19.6%) |

0.72 |

Hawali |

177 (16.7%) |

170 (15.5%) |

|

Farwania |

173 (16.4%) |

174 (15.9%) |

|

Mubarak Alkabeir |

172 (16.3%) |

176 (16.1%) |

|

Ahmadi |

185 (17.5%) |

180 (16.4%) |

|

Jahra |

170 (16.1%) |

180 (16.4%) |

|

Education level4 |

|||

Middle |

528 (49.9%) |

522 (47.7%) |

0.3 |

High |

530 (50.1%) |

573 (52.3%) |

|

Parent education3 |

|||

Father |

|||

Not educated |

21 (2.2%) |

10 (1%) |

<0.001 |

1ry – 2ry school |

163 (16.8%) |

117 (11.4%) |

|

High school – diploma |

377 (38.7%) |

433 (42.3%) |

|

Bachelor – high degree |

412 (42.3%) |

465 (45.4%) |

|

Mother |

<0.001 |

||

Not educated |

81 (8.4%) |

42 (4%) |

|

1ry – 2ry school |

146(15.1%) |

143(13.7%) |

|

High school – diploma |

351(36.2%) |

389(37.2%) |

|

Bachelor – high degree |

391 (40.4%) |

472 (45.1%) |

|

Parent Occupation3 |

|||

Father |

|||

Not working |

17 (1.7%) |

13 (1.2%) |

0.23 |

Doctor-engineer– teacher |

383 (38.6%) |

435 (41.5%) |

|

Secretary, administrator |

244 (24.6%) |

268 (25.6%) |

|

Business |

41 (4.1%) |

50 (4.8%) |

|

Retired |

307 (30.9%) |

281 (26.8%) |

|

Mother |

|||

Not working |

299 (29.7%) |

288 (27.4%) |

0.14 |

Doctor-engineer– teacher |

279 (27.8%) |

310 (29.5%) |

|

Secretary, administrator |

259 (25.8%) |

309 (29.4%) |

|

Business |

12 (1.2%) |

9 (0.9%) |

|

Retired |

155 (15.4%) |

135 (12.8%) |

|

Complain from chronic disease4 |

|||

Yes |

185 (47.9%) |

201 (52.1%) |

0.66 |

No |

868 (49.3%) |

891 (50.6%) |

|

Table 2 shows that boys (58.5%) were more likely to consume breakfast five times per week than girls (45.7%) were (P<0.001). The most commonly consumed food item was bread, with more than half the sample (n=1,219) consuming bread alone or with other items for breakfast; however, no significant difference was found between girls and boys (P=0.75). Cereal with milk and pancakes/waffles were commonly consumed food items among girls (31.3% and 13.5%) than boys (25.7% and 9.5%), respectively (P=0.004), whereas eggs and processed meat were most commonly consumed among boys (47.8% and 8.7%, respectively) than among girls (30.4% and 3.3%, respectively) (P<0.001). The most common reason behind skipping breakfast among boys and girls was “not hungry”; this observed difference was statistically significant (24.5% and 29.6%, respectively; P=0.02). The second most reported reason for skipping breakfast was “not enough time”, for both boys and girls (14.8% and 14.4%, respectively; =0.24). On the other hand, no significant difference was observed between boys and girls in relation to other reasons for skipping breakfast, such as “weight management” and “family or friends do not eat breakfast”.

Variable |

Boys |

Girls |

P-value |

Breakfast consumption |

|||

Breakfast skipper (<5 times a week) |

439 (41.5%) |

595 (54.3%) |

<0.001 |

Breakfast consumer (≥5 times a week) |

619 (58.5%) |

500 (45.7%) |

|

Breakfast Food item |

|||

Fruit and Fruit juice |

183 (17.4%) |

188 (17.5%) |

0.91 |

Vegetables |

118 (11.2%) |

106 (9.9%) |

0.31 |

Cereals with milk |

270 (25.7%) |

336 (31.3%) |

0.004 |

Milk |

306 (29.1%) |

312 (29.1%) |

0.99 |

Bread |

607 (57.8%) |

612 (57.2%) |

0.75 |

Cheese |

342 (32.5%) |

338 (31.5%) |

0.61 |

Eggs |

502 (47.8%) |

326 (30.4%) |

<0.001 |

Processed meat |

91 (8.7%) |

35 (3.3%) |

<0.001 |

Coffee & tea |

315 (30%) |

317 (29.6%) |

0.84 |

Soft/energy drinks |

68 (6.5%) |

69 (6.4%) |

0.97 |

Pancakes and waffles |

100 (9.5%) |

145 (13.5%) |

0.004 |

Snacking |

|||

Never |

131(12.5%) |

111(10.2%) |

0.03 |

1-2 snacks/day |

599(57.3%) |

612 (56.3%) |

|

3 snacks/day |

211 (20.2%) |

218(20.0%) |

|

>3 snacks/day |

104(10%) |

147(13.5%) |

|

Main meals consumption |

|||

Every day |

756(72%) |

555(50.8%) |

<0.001 |

Sometimes (at least twice a week) |

141(13.4%) |

267(24.5%) |

|

Rarely (once a week) |

18(1.7%) |

41(3.8%) |

|

Never |

11(1.1%) |

14(1.3%) |

|

Regular lunch |

107(10.2%) |

181(16.6%) |

|

Regular dinner |

17(1.6%) |

34(3.1%) |

|

Frequency of purchased food from canteen |

|||

Never |

218(20.8%) |

310(28.4%) |

<0.001 |

Everyday |

473 (45.1%) |

339 (31.1%) |

|

1-2/week |

197 (18.8%) |

301 (27.6%) |

|

3-4 /week |

161 (15.4%) |

140 (12.8%) |

|

Table 2 Percentage of frequency of breakfast consumption and other meals among Kuwaiti adolescents based on gender

The benefits of breakfast, including provision of energy, helping in the achievement of good grades, enhancement of mood, and supporting good health, were more likely to be reported by girls (19.4%) than by boys (13.2%) with a P-value of <0.001. Almost 19% of boys reported that breakfast is a source of energy, and this percentage was significantly higher than that of girls 17% (P=0.01) (Data not shown). Generally, the results showed that girls were more likely to eat snacks than boys were (P=0.03). On the other hand, boys were more likely to regularly consume main meals daily than girls were (P<0.001). Furthermore, boys were more likely to purchase food from the canteen than girls were (P<0.001). Most adolescents (both girls and boys) reported that the reason for not eating from the canteen was “not feeling hungry” (16.9% and 12.4%, respectively). No significant differences were observed between the genders in this regard (P=0.37). The majority of students ate breakfast at home, with no significant difference between the number of boys who did, and the number of girls who did (39.4% and 38.6%, respectively; P=0.05). Girls were more likely to eat breakfast at school than boys were (9.4% and 7.4%; P=0.02).

As shown in Table 3, participants who consumed breakfast less than five times a week were significantly heavier, with a median value of the BMI z-score as 1.32 (2.2), than those who consumed breakfast more than five times a week with a median BMI z-score of 1.13 (2.3) (P=0.01). Similar findings were observed among boys (median BMI z-score = 1.6 vs. 1.25) and girls (1.12 vs. 0.99) separately. More than half of the girls (59.7%) reported being physically inactive compared to boys (37.6%) (P<0.001). The number of boys who reported being physically active almost daily was twice (34%, n=357) that of girls (15.1%, n=165). Sixty-three percent of girls and 54% of boys reported watching TV and/or using electronic devices daily. Four variables (frequency of breakfast consumption, snacking, frequency of consumption of main meals other than breakfast, and frequency of physical activity) were built into logistic regression models separately. Adjusted and unadjusted odds ratios were stated in Table 4. The lowest frequency of breakfast consumption was presented as a reference category.

Anthropometric measures |

Breakfast skipper (<5 times a week) |

Breakfast consumer (≥5 times a week) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

Mean±SD |

Mean±SD |

||

All sample (n=2029) |

|||

Body weight, kg |

64.6 + 21.5 |

62.6 + 21.3 |

0.02 |

Height, m |

1.59 + 9.4 |

1.59 + 10.1 |

0.96 |

BMI z-score * |

1.32 + 2.2 |

1.13 + 2.3 |

0.02 |

BMI for age category % (n) |

|||

Within normal BMI range |

40.6%(392) |

44%(467) |

0.02 |

Overweight / Obesity |

57.3%(553) |

52.4%(556) |

|

Below BMI range |

2.1%(20) |

3.6(38) |

|

Boys (n=1058) |

|||

Body weight, kg |

70.4 + 25 |

65.5 + 24 |

<0.001 |

Height, m |

1.63 + 0.10 |

1.61 + 0.11 |

0.03 |

BMI z-score* |

1.6 + 2.43 |

1.25 + 2.5 |

<0.001 |

BMI for age category % (n) |

|||

Within normal BMI range |

36%(154) |

41.5%(251) |

0.02 |

Overweight / Obesity |

62%(265) |

54.4%(329) |

|

Below BMI range |

2.1%(9) |

4.1%(25) |

|

Girls (n=1095) |

|||

Body weight, kg |

60.1 + 16.9 |

58.6 + 15.9 |

0.16 |

Height, m |

1.56 + 0.07 |

1.56 + 0.06 |

0.69 |

BMI z-score* |

1.12 + 2.14 |

0.99 + 2.1 |

0.2 |

BMI for age category % (n) |

|||

Within normal BMI range |

44.3%(238) |

47.4%(216) |

0.39 |

Overweight / Obesity |

53.6%(288) |

49.8%(227) |

|

Below BMI range |

2.1%(11) |

2.8%(13) |

|

Table 3 Differences in weight status according to breakfast consumption categories based on gender among studied population

All values mean (SD) unless stated otherwise, *Non parametric test, median (IQR) reported.

All potential confounders were derived from the baseline questionnaire. Table 4 shows that the unadjusted odds of overweight and obesity were 16% lower among Kuwaiti adolescents who consumed breakfast almost daily, compared to those who consumed breakfast less than five times a week (OR=0.84; CI: 0.70–1.00; P for trend 0.06). Further reduction (20%) in the probability of being at risk of overweight and obesity was observed to be statistically significant, after adjustment for potential confounders, with OR=0.80, CI: 0.67–0.96 (P for trend 0.02). The association between breakfast consumption categories and overweight and obesity were stratified by gender. A significantly lower adjusted odds ratio was shown among boys who consumed breakfast five times or more per week, with a 24% reduced chance of being overweight and obese (OR=0.76, 95% CI: 0.58–0.99, P for trend=0.04), but not among girls (OR=0.86, 95% CI: 0.66–1.11, P for trend 0.26). In all the models, odds ratios were less than one for the snacking variable; however, these associations did not reach statistically significant levels after adjustment for potential confounders.

|

Variables1 |

All participants |

Boys |

Girls |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Un-adjusted OR |

Adjusted OR |

Adjusted OR |

Adjusted OR |

|

||||

|

|

||||||||

|

Breakfast consumption status2 |

|

|||||||

|

Breakfast skipper (<5 times a week) |

1.01 |

1.01 |

1.01 |

1.01 |

|

|||

|

Breakfast consumer (≥5 times a week) |

0.84((0.70, 1.00) |

0.80(0.67, 0.96) |

0.76(0.58, 0.99) |

0.86(0.66, 1.11) |

|

|||

|

P for trend |

0.06 |

0.02 |

0.04 |

0.26 |

|

|||

|

Snacking3 |

|

|||||||

|

Never |

1.01 |

1.01 |

1.01 |

1.01 |

|

|||

|

1-2 snacks/day |

0.77(0.57, 1.04) |

0.75(0.55, 1.02) |

0.75(0.49, 1.14) |

0.75(0.47, 1.18) |

|

|||

|

3 snacks/day |

0.77(0.55, 1.09) |

0.77(0.54, 1.09) |

0.82(0.50, 1.33) |

0.71(0.42, 1.19) |

|

|||

|

>3 snacks/day |

0.64(0.44, 0.94) |

0.63(0.43, 0.94) |

0.66(0.38, 1.17) |

0.59(0.34, 1.02) |

|

|||

|

P for trend |

0.05 |

0.14 |

0.48 |

0.31 |

|

|||

|

Main meals consumption other than breakfast4 |

|

|||||||

|

Never |

1.01 |

1.01 |

1.01 |

1.01 |

|

|||

|

Rarely (once a week) |

1.29(0.46, 3.53) |

1.37(0.48, 3.86) |

1.10(0.18, 6.57) |

1.20(0.31, 4.68) |

|

|||

|

Sometimes (at least twice a week) |

1.09(0.45, 2.64) |

1.13(0.46, 2.77) |

2.44(0.53, 11.15) |

0.70(0.21, 2.30) |

|

|||

|

Everyday |

1.16(0.49, 2.76) |

1.12(0.46, 2.70) |

2.38(0.54, 10.49) |

0.67(0.20, 2.20) |

|

|||

|

Only regular lunch |

1.21(0.49, 2.69) |

1.26(0.51, 3.11) |

2.71(0.58, 12.52) |

0.79(0.23, 2.64) |

|

|||

|

Only regular dinner |

1.65(0.58, 4.69) |

1.65(0.57, 4.74) |

7.82(1.12, 54.55) |

0.77(0.19, 3.04) |

|

|||

|

P for trend |

0.84 |

0.77 |

0.19 |

0.66 |

|

|||

|

Frequency of physical activity5 |

|

|||||||

|

Never/ < twice a month |

1.01 |

1.01 |

1.01 |

1.01 |

|

|||

|

Usually (three times a week) |

1.08(0.87, 1.34) |

1.01(0.81, 1.26) |

0.76(0.55, 1.05) |

1.26(0.92, 1.72) |

|

|||

|

Always (5-7 times a week) |

0.82(0.66, 1.02) |

0.70(0.55, 0.88) |

0.56(0.41, 0.77) |

0.86(0.59, 1.24) |

|

|||

|

P for trend |

0.08 |

0.004 |

0.001 |

0.14 |

|

|||

Table 4 Odds ratios (95%CI) for overweight/obesity by frequency of breakfast consumption, main meal habit and physical activity among Kuwaiti adolescents for all participants and gender specific

1reference value

2Adjusted to age, gender, parental education and occupation, physical activity, snacking and main meal frequency

3Adjusted to age, gender, parental education, parental occupation, physical activity, breakfast consumption, and main meal frequency

4Adjusted to age, gender, parental education, parental occupation, physical activity, breakfast consumption, and snacking

5Adjusted to age, gender, parental education, parental occupation, breakfast consumption, main meal frequency and snacking

Among all Kuwaiti adolescents, neither boys nor girls showed significant associations between “main meal consumption breakfast”, and being overweight and obese. However, Kuwaiti adolescents who always participated in physical activity were more likely to be within normal weight (OR=0.70, 95% CI: 0.55–0.88; P for trend 0.004) compared to those who were physically inactive, after adjustment for potential confounders. The odds of being overweight/obese were (OR=0.56, 95% CI: 0.41–0.77; P for trend=0.001) lower in boys who participated in physical activity at least five times a week, compared to those who never participated in any activity. Among girls, no significant association between overweight/obesity and physical activity was found. Almost half of the students did not have knowledge about their height (42%) and/or weight (52%). The response rate of students’ perceptions of their weight status was 91.5% (N=1,972). In Figure 2A & Figure 2B, the responses indicate that almost 35% of those who responded perceived themselves to be overweight/obese (compared to 54.7% who were actually overweight/obese); 50% perceived themselves to be about normal weight (compared to 42% who were normal weight), and 15.1% perceived themselves to be underweight (compared to 2.9% who were underweight). The results showed misperceptions in both genders. Generally, although the measured overweight/obese category was underestimated among students, the measured normal weight was overestimated. Table 5 shows that the degrees of agreement were found to be fair between measured and perceived weight categories (K=0.32, P < 0.001) for all students, with an agreement percentage of 40.8%. Similar significant findings were seen when the Kappa statistic was separately carried out for boys and girls (K = 0.32 and 0.31, P < 0.001) with a percentage of agreement of 39.8% and 41.9%, respectively.

Perceived weight categories (N) |

Measured weight categories (N) |

Total |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Underweight |

Overweight/ Obese |

Normal weight |

||

Underweight |

36 |

56 |

202 |

294 |

Overweight/obese |

5 |

595 |

89 |

689 |

Normal weight |

17 |

421 |

551 |

989 |

Total |

58 |

1,072 |

842 |

1,972 |

Table 5 Number of participants across weight categories obtained by measured and perceived weight for all participants

Figure 2 (A & B) Percentage of Students based on measured (A) and perceived (B) weight status among all adolescents and gender specific.

The current study originated from a representative group of adolescents in the KNNS; all students in the selected schools where invited from all governorates in Kuwait, with a response rate of 92%. The overall aim of this study was to examine the association between overweight and obesity and breakfast consumption among Kuwaiti adolescents, based on gender. A high proportion of overweight/obesity was observed among Kuwaiti adolescents (56%) aged between 12 and 18 years, which is in agreement with the 2015 KNNS report’s.11 The gender-specific overweight and obese percentage was higher among boys (57.7%) than among girls (52%). The 2013 Arab Teens Lifestyle Study (ATLS) also showed a higher percentage of overweight and obesity among boys (50.5%) than among girls (46.5%), aged 14–19 years in Kuwait.24 In a country where obesity is the major health issue for children, it is important to investigate the possible risk factors responsible for overweight and obesity among Kuwaiti adolescents. This can help in identifying a target population for future intervention programs.

The results of the present study showed that a significant proportion of Kuwaiti adolescents skip breakfast, and this habit was reported more frequently among girls than boys. On the other hand, daily breakfast consumption among Kuwaiti adolescents was about 40%, with boys being more likely to consume breakfast daily than girls. This is in agreement with a recent study that reported that the percentage of daily breakfast consumption in the surveys of the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) ranged from 37.8% to 72.6% and that this behaviour was more common among boys.25 Although girls agreed on all the breakfast benefits listed in the questionnaire more than the boys did, our findings showed that girls were more likely to skip breakfast than boys. A previous survey of 6,728 adolescents in grades 5 to 12 demonstrated that weight-related concerns were common among adolescents and that girls were more likely to follow a diet regimen at some point in their life than boys.2

This may suggest that girls are more likely to be concerned about their weight and, therefore, may attempt to restrict their energy intake via skipping breakfast. The reason for such behavior was investigated in adolescent girls in an interview to assess the reasons for weight loss attempts, and it was found that the media and fashion industry exerted the strongest pressures on girls to be thin.27 However, the boys selected “source of energy” as a benefit for consuming breakfast more than the girls did. This may be related to the desire of boys to have a bigger, bulkier, and more muscular body shape, as described in a previous study. 28 This can be supported by our findings that eggs and processed meat were the most selected breakfast food items among boys. Both sexes reported in our study that the two main reasons behind skipping breakfast were “not hungry” and “not enough time to eat”. These reports are consistent with those previously described in an Australian and a northern Italian study.29,30 In our study, girls were more likely to eat snacks than boys were, while boys were more likely to consume main meals daily than girls were. Several published studies have shown similar results regarding meal patterns among adolescents.31‒34 Furthermore, in 2007, the SWEDES study showed that among adolescents (n=481) aged between 16 and 17 years, boys had more meals per day including main meals than girls, whereas girls had a higher intake of light meals.35 It is worth noting that the current study is the first to highlight the relationship between breakfast consumption and overweight/obesity among a large number of Kuwaiti adolescents. Across the breakfast consumption categories, significant inverse associations were observed between the frequency of breakfast consumption and overweight/obesity, independent of age, gender, parental education and occupation, physical activity, frequency of purchased food from canteens, snacking, and main meal frequency with OR=0.80 (95% CI: 0.67–0.96, P for trend=0.02) among all adolescents.

However, gender-specific analyses showed a significant inverse association between breakfast consumption and overweight/obesity only among boys. In contrast, in Emirati adolescents in Dubai, 36 a study showed no significant association between breakfast consumption and the risk of obesity among girls and boys. Different results may relate to unadjusted associations in the Dubai study. However, other studies found no association.7 These discrepancies may be partly related to differences in the ages of the adolescents studied, definitions of breakfast skipping, and the categorizations used to determine overweight and obesity. Other possible explanations may be related to the amount and type of food consumed for breakfast or other unhealthy behaviours, such as a high intake of confectionary and fast food. However, 13 out of 16 cross-sectional or cohort studies in a systematic review (2010) showed that breakfast had a protective effect against becoming overweight or obese.6 In addition, pooled data from a meta-analysis of three trials34,37,38 reported an increase in BMI in breakfast skippers (mean difference=0.78 kg/m2, 95% CI: 0.51–1.04) compared to breakfast eaters. Similar findings in a recent study of 906 Kuwaiti children aged 14–19 years showed that avoidance of breakfast was positively related to BMI and waist circumference.24

In the KBOS, physical activity was negatively associated with the risk of overweight and obesity. However, the protective effect of being physically active on the risk of overweight/obesity was significant among boys, but not among girls. This is in accordance with a study by Mota et al.,39 in which the effect of physical activity on obesity among adolescents was investigated. The study showed that boys who were moderately active were more likely to be within the normal weight. Results from the E-MOVO project15 showed a significant association between physical inactivity and overweight among adolescents 13–16 years of age, after adjustment for potential confounders. Representative samples from 41 westernized countries of the HBSC study40 showed that overweight was consistently and negatively associated with breakfast consumption and moderate to vigorous physical activity. Regardless of gender, the frequency of snacking and regularity in main meal consumption other than breakfast were not seen as predictors of the risk of overweight and obesity among Kuwaiti adolescents, after adjustment for potential confounders. This could have been due to the difficulty in obtaining valid information on dietary habits among adolescents. On the other hand, different results were observed in the Dubai study,36 which found a statistically significant difference between snacking and obesity in girls (P = 0.044), but not in boys. This may suggest that factors other than snacking, which were not adjusted for in the previous study, may have a greater influence on the risk of obesity. This study found that the misperception of actual weight among Kuwaiti adolescents was high, with a fair agreement between perceived and measured weight status. Overweight/obese adolescents in this study were more likely to underestimate their weight status. This result is in accordance with an earlier study among Kuwaiti children aged 11–14.19 In addition, in 2010, 83% of Kuwaiti mothers incorrectly perceived their children’s weight status. These findings may highlight the lack of awareness of normal weight status among the Kuwaiti community, which can lead to future health complications and thus the need for early obesity prevention and treatment campaigns.

This study is unique because it was carried out on a large and homogenous sample, where all invited schools participated in the KBOS. The generalizability of our findings is further strengthened by the high individual response rate (92%) from all governorates, which indicate that the study population was a good representative sample of adolescents living in Kuwait. In addition, weight and height were measured, and subsequently used to calculate BMI for age and gender in our study, while most of the other studies used self-reported measures.

However, this study was cross-sectional, and thus may not adequately explain the existing association between breakfast consumption and overweight/obesity. Several possible explanations have been proposed. One potential explanation for the significant association is that obese people usually underreport their food intake, which means they may also underreport their breakfast consumption. Another reason could be that breakfast skippers may choose unhealthy food to make up for a missed breakfast. Another possible explanation is that skipping breakfast tends to be grouped with other unhealthy dietary factors such as physical inactivity; therefore, overestimation of the effect could possibly have occurred from residual confounders such as household income, dieting, family history of obesity, and smoking.6 No universal definition of breakfast consumption exists, which makes comparison with other studies difficult. It will be necessary to evaluate breakfast consumption as a healthy behaviour over time, among adolescents, which was not investigated in this study.

The KBOS study is the first to provide a comprehensive context of breakfast consumption among Kuwaiti adolescents. The observed positive association between breakfast skipping and physical inactivity in the current study highlights the importance of improving the overall quality of breakfast and regularity in breakfast consumption, in line with any physical activity interventional campaigns.41

Longitudinal design studies are necessary to explore causality between lifestyle-related factors and overweight/obesity in adolescents. On the other hand, future interventions could explore ways to modify eating behaviour at both individual and societal levels. For example, pancakes/waffles and processed meats were commonly consumed among Kuwaiti adolescents and could be targeted as possible areas that need intervention. Furthermore, emphasis should be placed on the consumption of fruits and vegetables for breakfast during dietary intervention for adolescents, to improve the quality of breakfast.

The high percentage of overweight/obesity and the significant misperception observed among Kuwaiti adolescents is an alarming sign of future adverse health consequences. Therefore, there is a need to tailor nutrition advice based on age and BMI, to ensure adolescents are equipped to make healthy breakfast choices within a healthy lifestyle.

Skipping breakfast, meal frequency, snacking, and physical inactivity were investigated as possible factors for overweight and obesity in 2,153 Kuwaiti adolescents. The results showed an inverse association between the frequency of breakfast consumption and overweight and obesity among Kuwaiti adolescents. This inverse association was seen more clearly among boys than girls.

We thank Fahima AlEnizi, Nawal AlDelmani, Fatima Alshimali, Mariam Alenizi, Hanan Abas, AlAnoud Alsumait of Research and Nutrition Education departments in Food and Nutrition Administration for data collection and data entry. MA, WH, EA and NA helped with early work on the development of the methods. MA, WH and EA designed the research; MA and EA conducted the research. MA and WH analysed data, and prepared the figures and wrote the manuscript. MA and WH are responsible for the final version of the manuscript. All authors participated in review and revision of the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

©2018 Dwairji, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.