eISSN: 2576-4470

Review Article Volume 2 Issue 6

Department of Sociology, University of Wheaton College, USA

Correspondence: Henry H Kim, Department of Sociology, University of Wheaton College, 501 East College Avenue, Wheaton, IL, USA, Tel (630) 752-5226, Fax (630) 752-5294

Received: March 09, 2018 | Published: December 10, 2018

Citation: Kim HH. Missionary networks and Korea: social network analysis and complexity science? Sociol Int J. 2018;2(6):566-574. DOI: 10.15406/sij.2018.02.00102

This social network analysis (SNA) exploratory paper investigates Protestant missionary networks concerning Korea at the turn of the 20th century.1 Given the numerous major events in Korea’s history (gross understatement) from the opening of its trade borders to Japan (1876) and subsequent Western penetrations (the 1882 “Shufeldt” and subsequent treaties) to the 21st century2 there cannot be a direct connection regarding the growth of Protestant from the 1880s to the present. Nonetheless, something(s) or some person(s) fostered the burgeoning of Protestantism at the turn of the 20th century.3

There are three basic questions that will be addressed in this paper. First, what were the missionaries’ social networks in Korea from 1868 to 1905? This can been visualized and specified via sociograms and SNA. Second, what contributions can SNA make regarding the historiography of these networks? SNA metrics may help qualify which missionaries or networks were “important.” Third, how can the intersection of historiography and SNA are advanced? Can SNA, as a subset of complexity science (CS), be used with other subsets of CS to engage with historical documents, historians, social scientists? Accordingly, I will conclude this paper by framing SNA into a larger heuristic framework of complexity science (CS) in general–that is, a relationship between parts and wholes,1–34 and four elements of CS in particular:

This paper does not claim that SNA or CS is a new panacea to trump traditional historiography. I merely want to suggest that perhaps, in light of the paucity of such an engagement, that it is academically worthwhile to entertain such an inquiry.

SNA5 and historiography

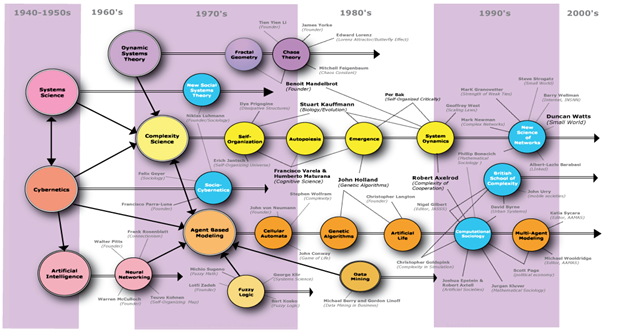

Although SNA has deep roots in sociology6 it must also be contextualized within a field of CS sees below (Figure 1). Moon (2014:3) noted with respect to historiography: “Increasingly historians are using computer and quantitative methods to address questions in history.”7 Further, almost every discipline I can think of has some representative scholarship delving into SNA and CS.2–4 Although an extensive literature review exists regarding the intersection of SNA and historiography,5,6 most of the scholarship is skewed with references of the words “networks” or “social networks” and few employ the mathematical concepts or provide the metrics and sociograms of social network analysis. Accordingly, there are a few works that do employ historiography (well) with SNA elements well.6–10 If the intersection of historiography and SNA is scarce in general, this crossover appears to be entirely absent with respect to Asian studies in particular.

Figure 1 Although SNA has deep roots in sociology it must also be contextualized within a field of CS.

SNA and particular missionaries in Korea

Below is a chart of the ten primary sources I analyzed in this paper and a sociogram when combining all of the vertices and edges (Table 1 & Figure 2).8

|

File name |

# of (including redundant) vertices |

Emphasis of degree from Ego |

Years |

|

Allen MSS |

2794 |

Out-degrees |

1884-1910 |

|

Rossi |

92 |

Out-degrees |

1880-1896 |

|

Loomis |

208 |

Out-degrees |

1883-1907 |

|

Kenmure |

162 |

Out-degrees |

1900-1905 |

|

Appenzeller |

693 |

Both in- and out-degrees |

1884-1902 |

|

Sill |

188 |

Both in- and out-degrees |

1894-1897 |

|

Moffett (I) |

84 |

Out-degrees |

1868-1893 |

|

Nursing |

34 |

Out-degrees |

1894-1901 |

|

Underwood I |

99 |

Out-degrees |

1885-1910 |

|

Underwood II |

50 |

Out-degrees |

1885-1910 |

|

Underwood III |

62 |

Out-degrees |

1885-1910 |

|

Underwood IV |

38 |

Out-degrees |

1885-1910 |

|

Underwood V |

89 |

Out-degrees |

1885-1910 |

|

Despatches |

2871 |

Out-degrees |

1883-1905 |

|

All Files |

7464 |

1886-1905 |

Table 1 I analyzed in this paper and a sociogram when combining all of the vertices and edges

Below are some of the delimited findings with specific SNA metrics (in-degrees, out-degrees, between centrality, and Page Rank) (Table 2).9,10

|

Actor |

In-Degrees |

Actor Typej |

|

HN Allen |

211 |

FM/P |

|

HG Appenzeller |

28 |

FM |

|

W Wright |

14 |

MA |

|

FF Ellinwood |

13 |

MA |

|

Thomas F Bayard |

13 |

P |

|

John Hay |

8 |

P |

|

HG Underwood |

8 |

FM |

|

Alex Kenmure |

7 |

MA |

|

James G Blaine |

7 |

P |

|

Henry Loomis |

6 |

MA |

Table 2 Top 10 In-Degrees (1868-1905)

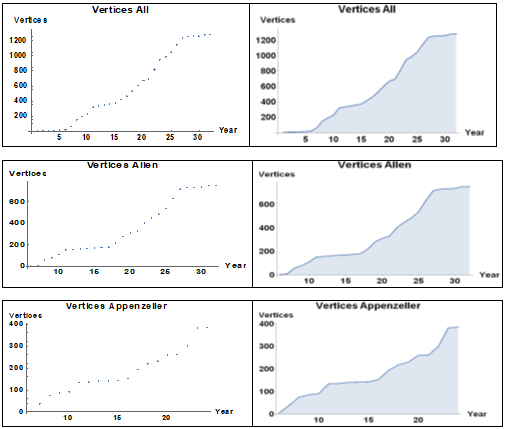

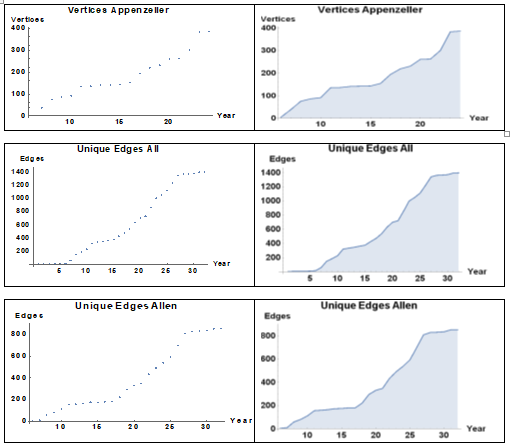

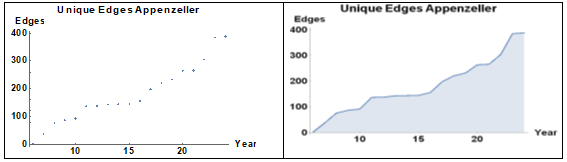

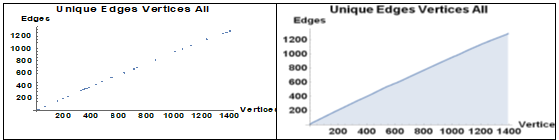

If in-degrees represent an actor’s “prestige” or social status11,12 and out-degrees represent an actor’s scope in a network,13 then Allen is without equal and Appenzeller is a consistent (but distant) second (Table 3–5). Between centrality measures notes how many times a particular node is on the shortest path between any two given nodes in the network. Thus, Allen is on the shortest path between any given two nodes in this network 1,245,270 times (and Appenzeller score is 729,473). Finally, Page Rank employs the Google algorithm to ascertain weighted in-degrees (“backlinks”) in determining important web pages. Accordingly, if Allen and Appenzeller were web pages they would have dominated the internet traffic with respect to Protestant missionary networks in Korea during their respective timeframes. Thus, these four directed-graph measures demonstrated that my findings were consistent with other network research concerning a skew in the concentration of nodes.14,15 The “importance” of Allen’s impetus in Korea was also consistent with two other respective historiographic scholars.16,17 Table 6 However, given the particular primary sources that were analyzed there is much room for integrating more missionary letters and thus re-calculating SNA metrics. Nonetheless, based on the data I was able to access, my SNA findings confirm and specify how “important” Allen and Appenzeller were regarding missionary networks. Currently my research has continued to move (slowly) towards CS. Let me quickly provide two charts of edges (ties) and vertices (nodes) that I used these data points in the subsequent SNA and CS discussions of this paper. Table 7 One book that I recently and randomly stumbled upon was by Moon who used historical data to test “models for innovation based on the growth of historical social networks.”11 In evaluating eight different technological advances he posited that social networks grew via scale-free networks12 in the form of power laws when mapping “important events” as a function of time. Accordingly, he claimed that “behind every new emergence of a technical product is a growing social network associated with that technology.” The notion that nodal growth can move from linear to non-linear or exponential patterns is not new. As a corollary, Zipf27 discovery of power laws and word frequencies made such an impact on Benoit Mandelbrot28 that the latter employed this scale-free logic in his dissertation; he would eventually become the father of another aspect of CS, fractal geometry. Fractal patterns have also been found in the growth of cities and respective infrastructure and the relationship between a single tree and the tree distributions within the respective forest based on “metabolism and allometry”. In examining the missionary sources for this paper, I wanted to test Moon’s power-law association with nodal growth. I did this by plotting both the growth of vertices and edges for each source and by combining all of the sources together. I plotted the data with “Year” on the horizontal axis and “Vertices” (vertices are also known as nodes which represent particular missionaries or actors) or “Edges” (edges are also known as the connections which represent letters or degrees of separation) on the vertical axis and as a function of time. Below are the respective charts for “All” of the data combined and for Allen and Appenzeller MSS, in plotting unique vertices and edges as a function of time. Graph 1 & Graph 2 represents the graph on the left provides the actual data points and the graph on the right connects the actual data points to create a continuous graph. Although I ran tests on all of the primary sources, based on the SNA metrics and graphs there does not seem to be a power law function. Granted, there is an increase in vertices and edges in time, as would be expected, “unfortunately” the growth appears to be linear. I ran one more test, with edges on the vertical axis and vertices on the horizontal axis, to ascertain if a power law existed (as a function of time)– the results below show an almost perfectly linear function: Further research is required to ascertain the conditions of when social network nodal growth moves from linear to non-linear power laws.

|

Actor |

Out-Degrees |

Actor Type |

|

HN Allen |

568 |

FM/P |

|

HG Appenzeller |

340 |

FM |

|

HG Underwood |

15 |

FM |

|

Alex Kenmure |

12 |

MA |

|

S Moffett |

11 |

FM |

|

Ella Appenzeller |

11 |

FM |

|

John MB Sill |

9 |

P |

|

Sally Sill |

7 |

P (Relative) |

|

Gordon Paddock |

6 |

P |

|

DW Deshler |

5 |

B |

Table 3 Top 10 Out-Degrees (1868-1905)

|

Actor |

Betweens centralityk |

Actor Type |

|

HN Allen |

1,245,270 |

FM/P |

|

HG Appenzeller |

729,473 |

FM |

|

HG Underwood |

42,479 |

FM |

|

Alex Kenmure |

41,947 |

MA |

|

W Wright |

36,663 |

MA |

|

S Moffett |

33,724 |

FM |

|

FF Ellinwood |

32,464 |

MA |

|

WB Scranton |

27,711 |

FM |

|

Thomas F Bayard |

25,271 |

P |

|

Ella Appenzeller |

21,673 |

FM |

Table 4 Top 10 Between ness Centrality (1868-1905)

|

Actor |

Page Rank |

Actor Type |

|

HN Allen |

303.5635 |

FM/P |

|

HG Appenzeller |

155.758 |

FM |

|

HG Underwood |

8.187766 |

FM |

|

Alex Kenmure |

6.978749 |

MA |

|

FF Ellinwood |

6.037348 |

MA |

|

S Moffett |

5.93337 |

FM |

|

W Wright |

5.632819 |

MA |

|

Ella Appenzeller |

5.286218 |

FM |

|

Thomas F Bayard |

5.011814 |

P |

|

John MB Sill |

4.005829 |

P |

Table 5 Top 10 Page Rank

|

Time |

Year |

All |

Allen |

Ross |

Loomis |

Kenm |

Appezellerr |

Sill |

Moffett |

Nursin |

Underwood |

|

1 |

1868-1878 |

3 |

3 |

||||||||

|

2 |

1868 1880 |

6 |

3 |

||||||||

|

3 |

1868-1881 |

6 |

3 |

||||||||

|

4 |

1868-1882 |

8 |

4 |

4 |

|||||||

|

5 |

1868-1883 |

10 |

4 |

2 |

|||||||

|

6 |

1868-1884 |

15 |

3 |

4 |

2 |

2 |

|||||

|

7 |

1868-1885 |

58 |

9 |

4 |

2 |

38 |

1 |

||||

|

8 |

1868-1886 |

147 |

58 |

2 |

76 |

3 |

|||||

|

9 |

1868-1887 |

185 |

80 |

6 |

3 |

87 |

5 |

||||

|

10 |

1868-1888 |

226 |

111 |

6 |

6 |

92 |

7 |

||||

|

11 |

1868-1889 |

319 |

155 |

6 |

7 |

137 |

7 |

7 |

|||

|

12 |

1868-1890 |

333 |

159 |

8 |

9 |

138 |

11 |

8 |

|||

|

13 |

1868-1891 |

345 |

164 |

8 |

9 |

143 |

12 |

9 |

|||

|

14 |

1868-1892 |

361 |

172 |

10 |

144 |

17 |

10 |

||||

|

15 |

1868-1893 |

375 |

174 |

10 |

12 |

145 |

20 |

14 |

|||

|

16 |

1868-1894 |

425 |

179 |

20 |

12 |

156 |

16 |

8 |

14 |

||

|

17 |

1868-1895 |

471 |

180 |

21 |

12 |

198 |

18 |

14 |

|||

|

18 |

1868-1896 |

536 |

220 |

21 |

221 |

19 |

15 |

||||

|

19 |

1868-1897 |

629 |

295 |

13 |

232 |

19 |

14 |

15 |

|||

|

20 |

1868-1898 |

698 |

330 |

13 |

264 |

16 |

15 |

||||

|

21 |

1868-1899 |

721 |

347 |

17 |

266 |

15 |

|||||

|

22 |

1868-1900 |

855 |

432 |

17 |

10 |

304 |

16 |

||||

|

23 |

1868-1901 |

997 |

491 |

17 |

10 |

385 |

17 |

17 |

|||

|

24 |

1868-1902 |

1047 |

537 |

388 |

18 |

||||||

|

25 |

1868-1903 |

1109 |

592 |

17 |

12 |

23 |

|||||

|

26 |

1868-1904 |

1221 |

698 |

17 |

15 |

26 |

|||||

|

27 |

1868-1905 |

1339 |

808 |

17 |

21 |

28 |

|||||

|

28 |

1868-1906 |

1360 |

828 |

17 |

29 |

||||||

|

29 |

1868-1906 |

1364 |

830 |

17 |

31 |

||||||

|

30 |

1868-1907 |

1370 |

834 |

19 |

31 |

||||||

|

31 |

1868-1908 |

1391 |

851 |

19 |

35 |

||||||

|

32 |

1868-1910 |

1394 |

852 |

37 |

Table 6 Unique Edges

|

Time |

Year |

A11 |

Allen |

Ross |

Loomis |

Kenm |

Appezeller |

Sill |

Moffett |

Nursing |

Underwood |

|

1 |

1868-1878 |

5 |

5 |

||||||||

|

2 |

1868 1880 |

9 |

4 |

||||||||

|

3 |

1868-1881 |

9 |

4 |

||||||||

|

4 |

1868-1882 |

12 |

5 |

7 |

|||||||

|

5 |

1868-1883 |

15 |

5 |

3 |

|||||||

|

6 |

1868-1884 |

23 |

4 |

5 |

3 |

4 |

|||||

|

7 |

1868-1885 |

65 |

10 |

5 |

3 |

38 |

2 |

||||

|

8 |

1868-1886 |

154 |

59 |

3 |

75 |

5 |

|||||

|

9 |

1868-1887 |

192 |

81 |

7 |

4 |

86 |

7 |

||||

|

10 |

1868-1888 |

231 |

112 |

7 |

5 |

91 |

9 |

||||

|

11 |

1868-1889 |

322 |

154 |

7 |

6 |

135 |

11 |

9 |

|||

|

12 |

1868-1890 |

336 |

158 |

9 |

8 |

136 |

15 |

10 |

|||

|

13 |

1868-1891 |

347 |

163 |

9 |

8 |

141 |

15 |

11 |

|||

|

14 |

1868-1892 |

361 |

169 |

10 |

142 |

19 |

12 |

||||

|

15 |

1868-1893 |

374 |

171 |

12 |

11 |

143 |

22 |

15 |

|||

|

16 |

1868-1894 |

420 |

176 |

19 |

11 |

154 |

11 |

12 |

15 |

||

|

17 |

1868-1895 |

466 |

181 |

20 |

11 |

194 |

11 |

15 |

|||

|

18 |

1868-1896 |

531 |

219 |

20 |

219 |

11 |

17 |

||||

|

19 |

1868-1897 |

607 |

280 |

12 |

231 |

11 |

14 |

17 |

|||

|

20 |

1868-1898 |

672 |

313 |

12 |

261 |

16 |

17 |

||||

|

21 |

1868-1899 |

694 |

330 |

16 |

262 |

17 |

|||||

|

22 |

1868-1900 |

818 |

402 |

16 |

13 |

300 |

18 |

||||

|

23 |

1868-1901 |

948 |

447 |

16 |

13 |

383 |

17 |

19 |

|||

|

24 |

1868-1902 |

990 |

485 |

386 |

20 |

||||||

|

25 |

1868-1903 |

1049 |

538 |

16 |

15 |

24 |

|||||

|

26 |

1868-1904 |

1148 |

633 |

16 |

17 |

26 |

|||||

|

27 |

1868-1905 |

1240 |

717 |

16 |

23 |

28 |

|||||

|

28 |

1868-1906 |

1256 |

732 |

16 |

29 |

||||||

|

29 |

1868-1906 |

1260 |

734 |

17 |

30 |

||||||

|

30 |

1868-1907 |

1263 |

737 |

17 |

30 |

||||||

|

31 |

1868-1908 |

1282 |

752 |

17 |

34 |

||||||

|

32 |

1868-1910 |

1285 |

753 |

36 |

Table 7 Unique vertices

Graph 1 The graph on the left provides the actual data points and the graph on the right connects the actual data points to create a continuous graph.

Graph 2 The graph on the left provides the actual data points and the graph on the right connects the actual data points to create a continuous graph.

|

Most sent in total #s |

Most sent per million |

|

1 United States 127,000 |

1 Palestine 3,401 |

|

2 Brazil 34,000 |

2 Ireland 2,131 |

|

3 France 21,000 |

3 Malta 1,994 |

|

4 Spain 21,000 |

4 Samoa 1,802 |

|

5 Italy 20,000 |

5 South Korea 1,014 |

|

6 South Korea 20,000 |

6 Belgium 872 |

|

7 United Kingdom 15,000 |

7 Singapore 815 |

|

8 Germany 14,000 |

8 Tonga 619 |

|

9 India 10,000 |

9 United States 614 |

|

10 Canada 8,500 |

10 Netherlands 602 |

Appendix 1 Regarding global missionaries and diaspora populations (CSGC 2013:76 and 83) to help visualize the reversals: Missionaries sent 2010

|

Source country |

Diaspora |

Christians |

Muslims |

Hindus |

Buddhists |

|

Mexico |

137,751,000 |

132959000 |

2,100 |

6,500 |

0 |

|

Bangladesh |

87,873,000 |

446,000 |

24,728,000 |

60,785,000 |

0 |

|

Argentina |

68,156,000 |

60,574,000 |

0 |

2,800 |

0 |

|

China |

60,580,000 |

7,095,000 |

571,000 |

0 |

15,717,000 |

|

India |

41,319,000 |

2,716,000 |

22,099,000 |

14,289,000 |

0 |

|

South Korea |

30,453,000 |

3,245,000 |

310 |

0 |

0 |

|

Russia |

24,063,000 |

15,646,000 |

2,618,000 |

0 |

0 |

|

Pakistan |

22,055,000 |

52,200 |

19,026,000 |

2,909,000 |

0 |

|

United States |

18,267,000 |

14,396,000 |

216,000 |

0 |

0 |

Appendix 2 Regarding global missionaries and diaspora populations (CSGC 2013:76 and 83) to help visualize the reversals: Top 10 Diasporas by source country

Conclusion and SNA and other employable tools of CS

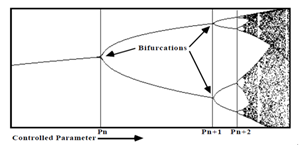

This paper provided a particular case study of selected missionary primary sources and the development of Protestantism in Korea at the turn of the 20th century. As noted earlier, SNA is part of a larger framework of CS; SNA is a part of the whole. For example, using weather forecasting as an illustration of parts, feedback interdependency, and wholeness, “the nature of weather forecasting is such that forecasts extending three days or more into the future require an accurate knowledge of conditions over the whole of the Earth at any one time, including knowledge of sea-surface temperatures”.29 SNA and CS are not “new” per se but the “newness” stems from requisite technology to crunch the (large amounts of) data and ascertain the formation of patterns.13 In concluding this paper, please allow me to make a small divergence and comment on some historiographic possibilities regarding SNA and four other elements of CS. As noted, though my data does not match a power law with respect to nodal growth, there are several other aspects of CS that should be considered for further investigation. First, as noted by Per Bak’s (1996) theoretical experiments of self-organized criticality (see image below), is there a tipping point regarding the “explosion” of social networks once a threshold is crossed? Figure 3 Is there some metric – or a Feigenbaum Constant–that evinces an equilibrium point between the “edge of chaos” or phase transitions? For example, Moon (2014:29) noted: “The appellation ‘criticality’ refers to the possibility that the system will experience a significant event such as an earthquake or an avalanche in a sand pile. ‘Self-organized’ implies that after such an event, the system resets itself to eventually trigger another event. The system is said to be on the edge between order (no significant events) and chaos (unpredictability of events).” Second, clearly time-series should be considered when mapping social relations which are inherently dynamic. In fact, positive feedback loops and time series have been known to evince “chaos” even within a (mathematical) closed system. The classic bifurcation chart f(x) =r x(1–x) where 0< r< 4and 0<x<1 shows that there are only three outcomes based on the initial “r” value, a fixed point, bifurcations, or a chaotic region. And yet within this apparent disorder there a beautiful order exists known as the Feigenbaum Constant. Is there such a constant within social networks? Figure 4 & Figure 5 Third, if networks are scale-free via time what about in space? Fractal geometry is another rubric within CS and perhaps there is room for topographical explorations, networks, and historiography. “Recently these power law relationships have been found in the statistics of modern social networks.31 In the case of population of cities, this law says that there is no average city. There are a few large cities, a greater number of moderate cities and many smaller cities. This can be seen for the largest US cities in 1900…. What is surprising is that this same power law type relation holds for the ranking of US automobile makers in the early years of the industry....” Though I am personally fascinated with chaos and fractal patterns (a nuance between time order and spatial dimensions), I completely agree with Castellani and Hafferty (2009:19): “chaos theory and fractal geometry do inform complexity science. Still, while these two areas of study are part of the mathematics of complexity, they are not complexity science”.

Figure 5 Fractal geometry is another rubric within CS and perhaps there is room for topographical explorations, networks, and historiography.

Fourth and finally, Cellular Automata evinces that a set of simple rules fosters various (and sometimes very complex) outcomes. My personal favorite is the Sierpinski Triangle and there are at least three different ways to create this aesthetic wonder (Figure 6). There are multiple ways to make this triangle (iterations via: Rule 90, rolling a die,14 or cutting the middle of an equilateral triangle). And then I found that there were other CA rules that created this exact output (Rules 18, 22, 26, 82, 146, 154, 210, and 217). I was humbled in exploring these closed systems. In sum, the bifurcation chart shows that even with full knowledge of the starting conditions, once one enters a bifurcated or chaotic region one cannot predict with certainty a particular point in time (cf. the Heisenberg Principle of Uncertainty). The Sierpinski Triangle shows that even with a known outcome one cannot be sure which starting conditions led to the outcome. Self-organized criticality points to a point of phase transition where disorder can suddenly shift to equilibrium (or vice versa–hence “the edge of chaos” as in: ice-water-steam). If there is unpredictability within a closed system, how much more is it challenging to make inferences concerning open systems of human relationships? This is humbling as a social scientist who tries to look at historical data and make inferences. Not just understand–make inferences. I hoped this heuristic paper has allowed readers and respective scholars to have a better understanding of the interplay between historiography, SNA, and CS as we continue to research and teach about Asian societies and cultures (Appendix).

It is also interesting to note that Sunquist dedicated his book, The unexpected Christian century: The reversal and transformation of global Christianity, 1900-2000, to S.H. Moffett; he was the son of S.A. Moffett, one of the earliest American Protestant missionaries in Korea. Yet it is not only religious scholars who have noted Korea’s Protestant affiliation. For example, recently The Economist published an article titled, “The Economist explains Why South Korea is so distinctively Christian: Asia is mostly stony ground for Christianity‒except in Korea. Why?”15

Protestant developments in contexts

Whether one purports that religion serves as a Marxian opiate or a Weberian stimulant concerning social change,16 any discussion of the development of Protestantism in Korea must acknowledge a social-religious continuum. There is no shortage of explications (particularly from the missionaries’ and their sending agencies’ perspectives) that it was “God alone” Who enabled Korea to receive Jesus Christ as her personal Lord and Savior. Perhaps one of the most often cited religious explications for Korea’s spiritual growth is attributed to the “Nevius Method”.32‒34 However, since the “spiritual impetus” is not the focus of this paper and I have already teased out the respective nuances in a prior (historical theology) dissertation35,17 I merely note this particular bookend. At the other extreme of the continuum of (perhaps in diametric opposition to) “spiritual forces” is any combination of militaristic (gunboat diplomacy), political (territorial hegemony) and commercial factors (expansionism and the necessity to open new markets).18 Two representative historians who do not deny religious elements per se but would emphasize expansionism are Fred Harrington26,19 regarding concessions in general and through Allen (and respective networks) in particular and Wayne Patterson27,20 regarding Korean emigration to Hawaii in general and through Allen (and respective networks) in particular. Whereas the former emphasized the role of concessions in Korea and the latter emphasized the role of land and labor concerning sugar, in both scenarios American Protestant missionaries had a role in promoting American interests. Further, both Harrington and Patterson marshal historiographic evidence that Allen was a key hub that connected commercial, religious, and political interests between the U.S., Korea, and Hawaii.21 Finally, as most social-material relation changes occur within interplay of structure, agency, and contingency22 from the Korean’s perspective (agency) they may have been motivated to convert to Protestantism for purely religious motives and or via reactive ethnicity; self-identifying not only “what I am but also what I am not.” That is, adopting Protestantism as a Western religion may have not only symbolized the adoption of “progress” but it may have also symbolized a rejection of the “antiquity” of China (and Japan).23

1Those familiar with this phenomenon will recognize some (if not all) of the following representative names: Horace N. Allen, Henry G. Appenzeller, Mary and William Scranton, Horace G. Underwood, and Samuel A. Moffett. Korea continues to stand out regarding its Protestant-affiliation when compared to all of the other (South and East) Asian countries of the world. One may take for granted that South Korea’s population is currently 25 percent Protestant-affiliated. Around two centuries ago Westerners in general and Christian missionaries and their respective religions in particular were not welcomed. In fact, open attacks on and decapitations of religious foreigners were not uncommon. The relatively short history of Protestantism in Korea is all the more contrasted when considering reverse missions. Not only are both the global de-Christianization of the West and the de-Europeanization of Christianity descriptive realities (Gordon Conwell’s Center for the Study of Global Christianity, but currently Korean missionary outflows are greater than the respective Western missionary inflows. Accordingly, Rebecca Kim asked: “How did a small country where only 1 percent of the population was Protestant a century ago, become a Protestant powerhouse sending missionaries across the globe, including the United States?”

2For example, the CSGC report shows a jump of Christian growth by proportion from 1970 to 2020 from 18.3 to 36.1 per cent, respectively.

3See the Appendix for a brief overview of “Protestant developments in contexts.

4In no way is this paper intended to posit that SNA or CS “trumps” historiography. SNA and CS are merely another nuance of interpreting primary sources and an attempt to qualify and quantify “how important” certain actors (nodes) may have been in their respective networks.

5For an overview of the development of this methodology, cf. Linton C. Freeman, The development of social network analysis: A study in the sociology of science.

6Comte18 originally depicted the field of “sociology” as “social physics” and see. According to Moon (2014:12): “The idea of prosopography in sociology was developed in the 1930s as the study.19-23of the interaction of a number of players in history. It also has roots in the nineteenth century through Francis Galton who used many biographies of British scientists to study heredity, environment and genius.” Social anthropologists such as Elizabeth Bott24 and Jacob Moreno25 also delved into aspects of “prosopography” in their studies of kinships and visualized relationship via sociograms.

7For this paper, I used Excel to record the data, NodeXL to create sociograms, and NodeXL and Mathematica to calculate SNA metrics.

8According to Kang26 From 1873 on, John Ross and his brother-in-law, John McIntyre, both Scottish Presbyterian missionaries, preached the gospel to Korean residents in the China-Korea border region.

[8]I have tried to categorize persons with their respective social spheres: FM=Field Missionary Actor, MA= Missionary Administrator Actor, P=Political Actor and B=Business Actor.

9Between ness Centrality measures were rounded up to the nearest whole number.

10To be honest, this author had a hard time in ascertaining how the “number of events” was selected as a function of time. I wondered if there was a data selection bias to fit the theory; nonetheless Moon does provide an interesting heuristic with respect to time, nodes, and “innovation.”

11Scale-free networks have been evinced via SNA.19,30

12For example, although one can make a claim that IBM fostered the persecution of Jews by their patents on punch cards and readers and provided the technology for Mandelbrot28 to discover fractals, Ron Eglash (1999) makes a case that this mathematical concept existed in various African countries well before the existence of IBM.

13Assign each corner of the equilateral triangle 1-2, 3-4, and 5-6. Starting in any area of the triangle, roll the die and based on the outcome, move to the midpoint of the pre-assigned corner and mark that point, roll the die and mark the next midpoint and repeat.

14http://www.economist.com/blogs/economist-explains/2014/08/economist-explains-6

15The former posited that religion pacified proletariats under capitalism and also gave a false euphoria because species-being could only be attained via matter. The latter theorized how religious values (ideas) in the form of Protestantism could help foster the burgeoning of a new means of production, capitalism.

16Further, the coup d'état on December 4th, 1884, the injury to Prince Min, and the medical intervention of Dr. Horace N. Allen is so well known that this event has gained legendary status in Korea’s history of Protestant missionaries.

17For example, Shufeldt36 wrote a few years prior to the 1882 Korean-American Treaty of Amity and Commerce: “At least one-third of our mechanical and agricultural products are now in excess of our own wants, and we must export these products or deport the people who are creating them. It is a question of starving millions.”

18Harrington25 noted: “Allen could not claim to be a great man or an altogether noble one; but he lived in the midst of great events and left his mark upon the times. … Through those years [1884 to 1905] he helped in the development of American interests in the Far East. There was a religious interest – Allen was the first Protestant missionary to reside in the kingdom of Korea. There was an economic interest – the doctor obtained for American business men the best of the franchises granted in the Land of the Morning Calm. There was interest in the future of Chosen….” According to Kang:22 “In the summer of 1888, Allen succeeded in forming a syndicate which included some of America’s leading capitalists of the day. One of them was W.T. Pierce, who wanted to establish a gold mill. …W.T. Pierce went on to develop the most modern mechanized gold mine in Korea.”

19Patterson26 noted: “These considerations [by the Hawaiian Sugar Planters’ Association in 1896] of the supply, quality, composition, and price of labor are what initially led the planters to think about using Koreans to replace the Chinese as an offset to the Japanese. For the next six years, from 1896 to 1902, these considerations grew, particularly after annexation in 1896, making the perceived need for Koreans even more urgent. Thus when the American minister to Korea, Horace Allen, stopped in Honolulu on his way to Korea after home leave in the spring of 1902, the planters took advantage of this to discuss the feasibility of bringing Koreans to Hawaiʻi. Allen promised the planters that he would help them get Korean workers.”

20Allen was a central node regarding the Sandwich Islands through his connections with American missionaries in Korea and Hawaii, the Korean King, and David Deshler, step-son of Governor Nash of Ohio, who was a good friend of (President) McKinley. Patterson26 provides evidence that Allen was a key node connecting the HSPA, Deshler, Korean and U.S. officials, and missionaries. Harrington25 cites various sources from the Allen MSS to nuance a quid pro quo relationship between Allen and Deshler: “A native of Ohio, Deshler became a close friend of the Allens, helped them get promotion and was helped in turn. His interests were broad, but in due time he concentrated on steam and navigation and on shipping Korean laborers to the Hawaiian sugar fields. His work was applauded and approved by Allen.”

21Obviously one must begin to think of complexity science at this juncture.

22Social functions and boundary demarcations via religious praxis are obviously not new ideas and reactive ethnicity via religion has also been well noted among Korean immigrants in the U.S.37,38

23Xwestern religion may have not only symbolized the adoption of “progress” but it may have also symbolized a rejection of the “antiquity” of China.

None.

The author declares there is no conflict of interest.

©2018 Kim. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.