eISSN: 2576-4470

Research Article Volume 7 Issue 4

Universidad Tecnológica de México, Mexico

Correspondence: Rosa María Rosas Villicaña, Professor, Universidad Tecnológica de México, Mexico

Received: August 02, 2023 | Published: August 17, 2023

Citation: Villicaña RMR. Judicial ethics in Ibero America- towards a perspective of gender and modernity. Sociol Int J. 2023;7(4):211-216. DOI: 10.15406/sij.2023.07.00345

Some of the great challenges facing judicial ethics are directed towards technological advances and inequalities faced by the administration of justice and that must be addressed from Judicial Ethics to strengthen the efficiency, effectiveness and legitimacy of justice institutions and renew the foundations of organizational culture, therefore, these issues are addressed from a deductive methodology and with a gender perspective, also taking up for this analysis, the Twenty-third opinion, of February 21 of this year, of the Ibero-American Ethics Commission Court on the proposal for a partial reform of the Ibero-American Code of Judicial Ethics. Speakers: Maria Thereza Rocha de Asisis Moura, Octavio A. Tejeiro Duque and David Odóñez Solís (CIEJ, Opinions nd).

Keywords: justice, technology, humanity, humanitarian crises

This study is divided into three parts: in the first, the context of this digital age is addressed, showing the threat of humanity itself and the alternative through the path of rectitude, to restore the social foundations of peace and coexistence through the administration of justice. The materialist current of Hobbes and the moral philosophy of John Rawls and the analysis of the Mexican jurist Eber Betanzos are taken up again. Under these reflections arises the proposal to broaden the spectrum of recipients of this Model Code.

The second part focuses on technological tools as a trigger for transformation and improvement to achieve the ends to which the administration of justice aspires and it is proposed to include a new value in judicial ethics. Modernization is exposed as a pressing need in the justice systems, for which reason bases must be established in this Model Code that contribute to counteract inertia.

In the third part, conceptual distinctions are raised regarding the proposal of the new chapter on gender equality and non-discrimination, contained in the aforementioned Opinion and that supports the ethical commitments in the field of women's human rights, sustained in various international instruments such as CEDAW itself and leading to proposing the breadth of inclusive language to be non-sexist, for which reason inclusion is explored in the analysis by making gender diversity visible from the language in the Model Code.

Judicial ethics in the context of the digital age

Under a panorama plagued with contradictions, the second decade of the 21st century is passing, on a path where technological advances that transform social and knowledge relations are intertwined, with hostile circumstances in a globalized environment recently hit by the Covid-19 pandemic. and that has left deep traces in the human, social and economic costs, showing human fragility in the face of nature and the need to combine reason with moral sense to face one of the worst humanitarian crises that have put the highest interests in check that are made possible through peaceful and harmonious social coexistence.

This historical passage has shown more clearly that at a global level there are serious problems that require global responses such as the increase in inequality gaps in multiple aspects, the increasing ravages of climate change, wars and the disconcerting threats of the sophisticated artificial intelligence.

It is here where the voices of philosophical approaches must be heard with a higher tone to lead the dialogue of the rationality of what should be with the environment and recognize again the light of a direction that not infrequently gets lost on the path of Justice.

Indeed, Thomas Hobbes refers that men differ in many aspects of ordinary life and even at different moments of their lives they can differ from themselves (Levitan, sf), for this reason their nature is of a war condition, hence he resumed the Latin locution "homo homini lupus" when warning in human nature, the risk it has for the general well-being, when the particular interest surpasses it. Rules are needed, models of behavior that make peace and harmonious coexistence possible in society. The rule of the legal system is based precisely on achieving those goals and values that give cohesion to the community and guarantee the satisfaction of general interests.

For this reason, humanity is the protagonist of its worst threat and, paradoxically, its only hope to preserve the original pact that allows for the formation of an orderly and efficient society to achieve its goals under solidity through its institutions for the administration of justice. Then, the rules and sanctions must give the State monopoly strength to justify this great social pact.

However, role models cannot be justified without values and principles; it would be an empty shell if it does not consider the path of ethics and morality. In this sense, it is necessary to return to one of the main philosophers of the last century: John Rawls, who showed decades ago that we are in times of returning to basic moral concepts in society through what is good, straight and valuable as The philosopher concluded it,1 so that justice is a social good that must be brought to excellence in order to transcend from a mediocre or corrupt judge to an exemplary judge.

Following this line of analysis, Dr. Eber Betanzos leads us to remember that the social order to have solid foundations and achieve those ends in a structure in which judges are a fundamental part of the social structure and that justice transcends on fertile ground in moral virtues that lead the path of human dignity.1

Indeed, ethics frames the values that, emanating from society, are dynamic under the premise that derives from the original pact to put human desires and appetites before reason and the path to achieve the common good. Thus, judicial ethics, contained in the Ibero-American Code, regionalizes a guide of conduct that contains values and principles in which the actions of judges must adhere.

According to USAID, ethics in the public function is based on the fulfillment of its various roles to guarantee survival and collective security, to maintain social cohesion among its members of the organization and to jointly seek the necessary cooperation.

In the Colombian Code of Judicial Ethics, the code of ethics is a fundamental element to guide and evaluate the exercise of public duty and allows the generation of patterns of work behavior that require work behavior that requires public recognition of an ethical culture.

For Colombia, the Code of Ethics is considered as an initial tool in strengthening relations between the entity, officials and citizens.

The Model Code establishes the bases of an organizational culture in the Ibero-American judiciary, since as Hilda Heller mentions, this is a reflection of the cultural guidelines that take many years to settle in societies. Through these guidelines of conduct, always perfectible, they allow establishing the bases to guide directions and solutions to respond to the social demand for a prompt and correct administration of justice.

Although the Ibero-American identity shares cultural and geographical features and that have increased in the interaction of relations between nations and, consequently, in the judicial powers, it is also possible to recognize obstacles that have caused a crisis of legitimacy in the teaching institutions of justice and therefore weaken the rule of law. The judicial ideality to which the Model Code refers, is the path of orientation in the Ibero-American judicial powers, which finds support in the constitutional bases of the democratic states of the region.

But, what is the function then of judicial ethics? Is it an instrument directed only to those who have the honor of exercising justice? For all the public service in the judicial powers in their different competences? Or is it directed so that society can evaluate whoever administers justice? It would be worth rethinking who your recipients are.

Currently, the Model Code is especially addressed to the actions of judges, such as "the judge's intimate commitment to excellence and rejection of mediocrity";2 This is only an explanation of judicial suitability, an enlightening instrument of judicial ethical conduct that involves a commitment to excellence and permanent training for those who hold such high positions and nurtures ethical quality in the justice service.

Justice is not only embodied in who will decide the sense of resolution, that is, in the judges, since, to achieve efficiency in this commitment, it requires a good functioning of the entire organization in the administration of justice, of the public servants who participate, which also requires rectitude, excellence and professionalism in their actions, otherwise, consequently, the obstacles would be unleashed to achieve prompt and expeditious justice, for this reason, the popular phrase that It is attributed to the philosopher Seneca: "nothing seems so much to justice, as late justice."

In addition, the criterion that has not been approved for in Ibero-American nations would be collected as good practices, some consider as recipients all the personnel that are part of the judicial powers and that from their different roles contribute to the administration of justice as in the example of Guatemala (to mention just one example), in the Norms of Ethical Behavior of the Judiciary.

Indeed, from each of its trenches it is an operator in the justice administration institutions, it plays an important role in achieving that social good that is justice, under the main figure of the judges and their inclusion in the Code Model, will abound in the demand and confidence of the justice systems in Ibero-America.

Having a code of ethics and knowing it is not enough, for the public servant it is of little use to be aware of what is correct and what is not, if in the end he acts improperly, taking advantage of the circumstances derived from the circumstances derived from the activities assigned to them in the position they hold, access to confidential information or even decision-making power to obtain their own benefit.

Judicial ethics addresses the conscience to guide the conduct of those who administer justice, so it is also a mechanism of self-control and also of courage to continue on the path of what is right.

The digital value in judicial ethics

The digital age has put its own stamp on one word: transformation. Technological innovations, such as artificial intelligence, have an impact on all areas of society in a globalized environment, rushing to exceed the limits of knowledge without precedents and continue designing new models of social interaction with the advances of artificial intelligence. In this sense, it is essential to recognize ethical values, beyond the field of morality, as a necessity to maintain social cohesion under a rational axiological dialogue that leads the direction of technological advances that make justice systems more efficient.

In the final version of the Twenty-third opinion, of February 21, 2023, of the Ibero-American Commission on Judicial Ethics on the proposal for a partial reform of the Ibero-American Code of Judicial Ethics. Speakers: Maria Thereza Rocha de Asisis Moura, Octavio A. Tejeiro Duque and David Odóñez Solís, (CIEJ, Dictamenes sf). Emphasis was placed on a much more developed technological context than in 2006 when the Model Code was created. Through the use of new technologies, the transparency of justice institutions can be strengthened, which is also a social demand, as Inés Malvina3 considers in relation to the Code of Judicial Ethics in Argentina.

However, it is necessary to recognize the technological inequality gaps in the world and of course in Ibero-America, resistance to use and adapt to technological advantages within justice administration institutions deepens, which has a negative impact, it can they do not take advantage of the advantages that could be transformed to improve the administration of justice more quickly and fluently, whose general demand is for improvement, in other words, to achieve effectiveness and efficiency, the latter understood as the best use of resources, that is, to make more with less, reduce human errors in the use and above all, improve the time used in activities related to the administration of justice that generate transparency, speed, economy and less human wear, which in the workplace, would also improve working conditions both for judges and for everyone who performs a function in the administration of justice.

In short, it is possible to recognize the value of digital as a means to provide greater effectiveness and efficiency in the human right to access to justice, for which it is proposed to include it in the Model Code and implement it from this guide in order to take advantage of the resources technology and banish fears that judges may be replaced by artificial intelligence, confusing the possibility of automating some legal services, but it will never be possible to compromise discernment in a sentence that not only requires reason, but also intelligence judicial ethics to resolve each particular case and cannot be determined by any algorithm.

In incorporating the value of digital, the principles of the Model Code must be taken into account, which are the guide that determines what is right from what is wrong depending on each case and context, so there will be no algorithms, which insert the sense of justice depending on each case and circumstance that will lead to different resolutions.

The great paradox represented by technological innovations shows the two directions of a path: they can be oriented through ethical principles to form a great ally or, become a great threat to humanity, because clearly, this fourth industrial revolution has gestated a serious crisis: that of the ethical sense that disrupts social values and that are pillars on which the institutions of the administration of justice are founded.

It is here where it must be reaffirmed that the understanding and application of the law is not resolved with the rationality of a mathematical formula, but with reason linked to the sense of what is good, what is fair and what is correct, finding its main ally in ethics to guide behavior with universal values to act correctly both individually and collectively.

Technological innovations provide value for transformation and advances, so in addition to requiring a public policy that implements it in the spaces of the judiciary, an attitude is also required, which is why this incorporation into the Model Code is proposed and be part of the behavior guide; In other words, it would represent a great step for its institutionalization, as it forms part of the tools to meet the demand for excellence and professionalism that is required in the field of justice administration and take advantage of the advantages to improve and modernize all services and the rejection of mediocrity.

In other words, the purposes of judicial ethics require means to achieve it, which, as behavior guides, must be adjusted to a digital environment that increasingly demands the use of new technologies; As a consequence, a new principle will have to be considered in the Model Code, which is that of the culture of digital transformation, since they constitute the value core, since it provides tools to achieve an efficient, excellent and humanistic administration of justice, this in the international context of Human Rights in which we are immersed as an Ibero-American community.

Promoting a culture of technological transformation includes values and behaviors that promote among public servants new ways and ways of interacting, rationalizing, working and taking advantage of information and communication technologies (ICTs), emerging technology and e-justice media to institutional work and social demand in the delivery of justice.

In this context, it is also worth remembering the motto in Mexico during positivism: "Love, order and progress" Love as a means, order as a base and progress as an end (UAEH, sf). In the field of the judiciary, love, represent ethical values, order, rectitude and excellence in which the path and progress must be led, achieving with the use of technological tools, the social good of justice.

Thus, the social demands in the administration of justice within a digital governance demand equality and inclusion as nuclear values in the face of the challenges of a millennium that has begun with great imbalances and, in fact, are part of the commitments of the 2030 agenda as was established in the General Assembly in goal 16: Promote just, peaceful and inclusive societies.4

In e-justice, some of the values that must be taken up again in the case of digital policies of the Mexican judiciary with values such as judicial independence, equal access, judicial independence, accountability, expedited justice, impartiality, transparency, legality and progressivity, under the objectives of efficiency and effectiveness, access to justice, equality and legitimacy, which are clearly in harmony with the principles and values of the Ibero-American Code of Judicial Ethics and can be taken as good practices in the direction of the technologies in the actions of the operators in the administration of justice.

In this direction, the digital value must also be understood, the benefits that must be taken advantage of, such as user satisfaction, technical excellence, simplification, support and trust, inspection and adaptation, among others, but especially acceptance of change as highlighted by these digital policies. The simplification of technologies improves system administration, increases transparency and the possibilities of service improvement. Therefore, the technological transition ranges from the administrative areas and jurisdictional bodies that make possible the social demand for the administration of justice.

In the case of the Dominican Republic, it also undertakes the task of promoting digital transformations from the judiciary, considering in them a potential for Transformation and with a motto: 0% default, 100% access to justice and 100 % transparency. For this reason, a culture of transformation must be promoted, made up of values and behaviors that promote among public servants new ways and ways of thinking, interacting, working and taking advantage of information and communication technologies (ICT), emerging technologies and e-Justice media for institutional work and the administration of justice.

The breadth of the principle of equality and non-discrimination from the gender perspective in the Ibero-American code in the code of judicial ethics

The principles, according to the Model Code, constitute the evaluative nucleus and are guides in the conduct of the judges, as well as the final version of the Twenty-third opinion, of February 21 of this year of the Ibero-American Commission on Judicial Ethics, among other aspects. , addresses a proposal for a partial reform of the Ibero-American Code of Judicial Ethics. Speakers: Maria Thereza Rocha de Asisis Moura, Octavio A. Tejeiro Duque and David Odóñez Solís,5 focused on the principle of gender equality and non-discrimination on which it is considered appropriate to reflect.

Although, the gender perspective is generally adopted as: "an analysis model for the exercise of jurisdiction and interpersonal relationships among members of the judicial structure in the region, which contributes to the identification, attention, and treatment of practices and stereotypes that cause discrimination, avoid their reproduction, minimize their effects and provide an adequate confrontation”.5

This perspective must also be framed in light of women's human rights, whose commitments in Latin America are linked to the CEDAW Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women and which directly impact in justice administration services.

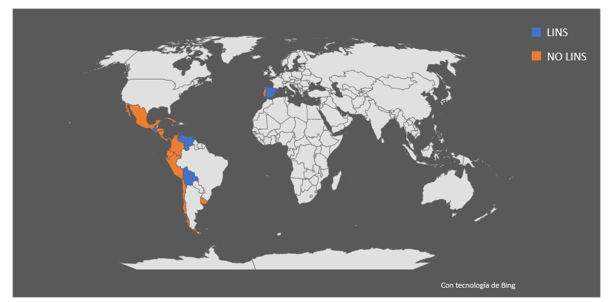

In order to show the panorama of these commitments and for which it is not only pertinent, but urgent to permeate the gender perspective in the Model Code, the following graph shows the States linked to this International Agreement and the Optional Protocol and shows the countries in Latin America that signed and ratified said protocol (Figure 1).

Figure 1 The following graph shows the States linked to this International Agreement and the Optional Protocol and shows the countries in Latin America that signed and ratified said protocol.

Source: Figure of own elaboration 2023.

Observatory for Gender Equality in Latin America and the Caribbean.

(Table 1) As can be seen, most of the Ibero-American countries signed and ratified this international instrument, except Honduras and Nicaragua, and the only ones that signed but did not ratify were Cuba and El Salvador. In this understanding, the inclusion of the principle of equality and non-discrimination is in accordance with the human rights of women.

|

Spain |

Signature of the protocol (2000) |

Ratification of the protocol (2001) |

|

Portugal |

Signature of the protocol (2000) |

Ratification of the protocol (2002) |

Table 1 Iberian Peninsula

Source: Fountain United Nations.

In the features that unite the historical aspects of Ibero-America are the relations of inequality in the public and private spaces of the roles of women. Each country, in its own self-reflection, must recognize the disproportionate number of women judges than men, of course, older than the latter, who even reveal themselves in their own language in the areas of the judiciary that are mostly directed at them: judges.

For this reason, returning to the fact that organizational culture represents a system of norms and values that reproduce the society to which they belong, it is necessary to incorporate knowledge and awareness tools in this area to generate changes in these spaces and linked to excellence and the commitment of those who provide the service in the judicial powers.

The use of inclusive language is warned in the Model Code, therefore, in relation to inclusive language, it is proposed to add "and not sexist", because these biases continue to contribute to the perpetuation of inequalities and discrimination. In effect, the author Ma. Ángeles Calero, maintains: "Do not forget that thought is modeled thanks to the word and that only what has a name exists.".6 For this reason, it is proposed to move towards a broad language, which names and respects sexual diversity, which in all areas of the judiciary to establish bases that give meaning to non-discrimination since through language the most subtle forms of discrimination are presented. , since they are the reflection of our values, our thoughts,

Gender is found in organizations, in individual identities between men and women, but it is generally absent in the norms and values that structure organizations, sexual and gender diversity, despite the fact that the National Survey on Diversity Sexual and Gender,7 in a statistical program with the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI), reported that in Mexico, the fifteen-year-old LGBTI+ population is made up of more than five million people7 invisible within of labor organizations. In short, the gender perspective and the inclusion of sexual and gender diversity must be contemplated in the principles of Judicial Ethics in Ibero-America.

Indeed, considering a change in the language in this Model Code towards inclusion is a consequence of the incorporation of the gender perspective, but it will not be enough to indicate inclusive, since sexism in language represents one of the most normalized forms of inequality that perpetuate a historical invisibility of the role of women as protagonists in the public and private spheres. Therefore, it is valuable to incorporate inclusive and non-sexist language in the Model Code, as some national codes of ethics have done (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Regulatory documents on judicial ethics of Ibero-American countries. Cited in the research sources section.

Source: Own elaboration, June 2023.

Despite the fact that inclusive and non-sexist language has been increasingly used in the institutional language of Ibero-American countries, such as: Bolivia, Spain, Guatemala, Puerto Rico and Venezuela.

It is important to specify that it is not only a matter of adding a feminine in the full wording of the Code, but of being gender aware in the actions of justice operators, so it is possible to mention the content of the gender perspective when judging established in six steps, as established in Mexico, the jurisprudence thesis 1a./J. 22/2016 (10th) What are they:

The steps that are established and are the bases in the design of the Protocol for Judging with a Gender Perspective in the case of Mexico and with a mandatory nature, are a valuable example in the updating of an evaluative guide of the Model Code that is oriented towards the balance and equality within the path of justice.

In this sense, it is considered important to clarify some conceptual tools for the best meaning and interpretation of the principle of equality and non-discrimination based on the principle of mainstreaming alluded to in said document.

The mainstreaming or transversality of genres. It is a term with multiple philosophical and moral charges, but for the purposes of this essay it could be focused as a process whose purpose is to achieve equality and eradicate gender discrimination, which is one of the principles proposed in the Twenty-third opinion, dated 21 February of this year5 of the Ibero-American Commission on Judicial Ethics, so it will seek to achieve equality through its various dimensions as mentioned by García Prince,8 so this principle contributes to closing the gender gaps.

On the other hand, the author Gisela Zaremberg9–12 considers it necessary to make the distinction between mainstreaming and institutionalization. On the one hand, he sees mainstreaming as: "an approach built historically to address forms of solving public gender problems",13–18 while the institutionalization of the gender perspective, to advance in solving problems gender audiences we care about.19, 20

Therefore, the inclusion of the gender perspective in the Ibero-American Model Code will strengthen the bases to achieve institutionalization and mainstreaming in the gender perspective.21,22

None.

There are no direct or indirect conflicts declared by author.

None.

©2023 Villicaña. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.