eISSN: 2576-4470

Review Article Volume 2 Issue 6

1Department of Political Science, University of Buea, Cameroon

2Department of Geography and Development Studies, University of Buea, Cameroon

Correspondence: Lotsmart N Fonjong, Department of Geography and Development Studies, University of Buea, Cameroon, Tel 23777513620

Received: May 15, 2018 | Published: December 31, 2018

Citation: Fonjong LN, Fokum VY. Increasing women’s representation in the Cameroon parliament: do numbers really matter? Sociol Int J. 2018;2(6):754-762. DOI: 10.15406/sij.2018.02.00134

This paper examines the relationship between increasing the number of female legislators in Cameroon and it impact on gender-related policy, from a critical analysis of the participation of individual parliamentarians in influencing parliamentary proceedings and decisions within existing parliamentary structures. The study uses the concept of descriptive and substantive representation within the framework of the critical mass theory to investigate the extent to which an increase in the presence of women in the Cameroonian parliament will affect the quality of women‘s issues presented to parliament. Eleven female parliamentarians were interviewed. The study reveals that an increase in the number of women does not significantly enhance substantive representation or women’s issues. It noted that while the profiles of female parliamentarians influence their participation in decision making structures within parliament, party discipline and the parliamentary system has more influences on the issues and policies debated and voted in parliament than numbers.

Keywords: substantive representation, descriptive representation, women issues

Gender and politics are at an important point in history as more and more women continue to gain entry into political office and senior positions in government.1 While the dominance of political scientists and elitist concepts of equity and democratic justice may help explain this trend, feminist scholars are concerned with the impact that the participation of women may have on the political system and the female community as a whole.2 Consequently, there is a growing body of literature dedicated to these studies with an overriding assumption that increasing the number of women among public officials would lead to the feminisation of policy.2‒4 However, the extent to which a relationship exists between numbers and impact is an empirical question. Recently in Cameroon, there has been a “clarion call” for more women to be represented in parliament. This call however does not question the impact of women so far in parliament; even during the multiparty system where the highest number of women (24) represented in parliament was registered during the legislative year 2007-2012. There is therefore little understanding as to how this increment will or has impacted on policies on women’s issues in a way different from previous years when there was very low representation.

The purpose of this paper is to investigate whether increasing the number of female legislators in Cameroon can automatically lead to the visibility of women’s issues and gender sensitive policies in parliament. In other words, how valid is it to say that female parliamentarians can adequately address women’s issues and represent women’s interests by their mere presence in parliament? It questions the individual profiles of female MPs as they influence their participation in parliament alongside their collaboration and interaction with the civil society and women’s organisations. Studies have advanced women’s interests along three lines: women’s traditional roles within patriarchal societies, as shaped by their bodies, sexuality, and possibility of giving birth; women’s participation in the labor market; and women’s opportunities to transform their roles to attain greater gender equality.5,6 The central area of debate has been whether to emphasize “practical” or “strategic” interests, stressing women’s everyday needs or more abstract feminist goals.6,7 This approach however essentializes women and according to Celis8 is theoretically untenable and undermines feminist concerns about heterogeneity and intersectionality. It risks flouting the differences between women at a particular place and time as well as failing to recognize that women’s interests may vary significantly across spaces and time.6 The second approach looks to the demands of the contemporary women’s movement to identify women’s interests6 which could be challenged on the grounds of privileging feminists concerns. It also assumes that women’s movements are free to articulate their demands. Celis et al.6,9 however portrays that women’s concerns are a priori undefined, context related, and subject to evolution. Referring to Cameroon therefore women’s interests include, but not being limited to, the following: health and child care, education, sexual and gender-based violence against women, female genital mutilation in parts of Cameroon, marriage and family law, environment and land-related resources, and control on reproductive health.

Literature acknowledges that there are complications in translating an increase in descriptive representation into an increase in substantive representation. It argues that the process “by no means guaranteed” the outcome5 and that the relationship between the number of women in parliament and the introduction of pro-women legislation is “complicated rather than straight forward”.10 There are two main theoretical approaches used by researchers when examining the potential link between the increase in the number of women legislators and their impact on women’s interests. These are: the critical mass theory and the politics of presence theory. Critical mass theory, emphasises the necessity of having an adequate number of women legislators, estimated at approximately 30%, rather than a few token women, as a necessary condition for the transformation of women’s status.11 The politics of presence theory is based on the idea that because women share life experience and interests, once they have been elected women legislators will have common grounds and on this basis will be able to transform parliament. They will also have sufficient common interest to make parliament’s policy output more women focused.12 Post-modern feminists are critical of the above premises of the critical mass and politics of presence theories which try to universalise women as a group. The debate is whether descriptive representation of women necessarily leads to substantive representation or is it wrong to essentialise women and consider them a homogenous group?

The context for more female Representation

The election of Liberia’s Ellen Johnson Sirleaf in 2005 as the first female president in Africa opened new window of opportunity for women, as Johnson is largely viewed as a role model on the continent that had hitherto not considered women for public roles. Feminist, particularly in Africa have used the Liberia’s example as a platform to strengthen their claim for women‘s right to political participation. As Carroll13 explains, this trend is replicated elsewhere, “increasing the number of women among governing elites has been a major concern for many feminist organizations. It is this concern that led, in part, to the creation of the Women’s Campaign fund, a political action committee that raises and distributes money to women candidates...mobilize members to work in the campaigns for women candidates, endorses the candidacies of women, contribute money to their campaigns”(Ibid) and in advancing women’s rights. highlights the importance of feminists’ movements to achieve women’s rights. The study demonstrates how mobilisation of civil society organisations across gender lines led to the passing of Domestic Violence legislation in Ghana. This therefore emphasizes the fact, and as stated by Gouws (2005) that political office-holding alone is insufficient in addressing gender equality; civil society organisations are critical.

A number of arguments have been put forward to justify calls for increased presence of women in parliament, mainly along three basic grounds. The first relates to equity and democratic justice seen from the point of ensuring the participation of all citizens and challenging unequal power sharing between men and women which result in unfair social and political processes. Women’s political inclusion will challenge the existing power structures and relations that undermine the consideration of women’s needs/interests in policy making.14 Similarly, Henig et al (2001:105) and Ahikire (2007) stress that; women should be entitled to at least fifty per cent representation at all levels to reflect the proportion of women in the population. It is also the case that the legitimacy of democratic political systems will be reduced if women are absent or underrepresented in key decision-making positions as public confidence in institutions may be diminished (Henig et al, 2001). There can therefore be no true democracy if women are excluded from positions of power. Proponents of this argument like Asiedu et al.,14 therefore maintain that including women in the political process engenders the political and economic benefits for both men and women.

The second argument is about the representation of interests where it is argued that: women‘s interests cannot be properly represented by men, in much the same way that it has been argued that the interests of the working class cannot be fully represented by the middle-class. The assumption is often that because women share descriptive characteristics, if elected to public decision-making office they will be sympathetic to group interests by taking actions that are favourable to women as a group. Ford (2002: 134) aptly captures this as she explains, “we assume that if someone shares our descriptive characteristics like sex, race, or other defining features, they will also share and protect our interests. Our image and interests are mirrored by the representative who is like us” (Ibid). Goetz (2006:88) echoes the argument of the 1995 Beijing Platform for Action that women’s equal participation in decision making is not a demand for simple justice but a necessary condition for women’s interest to be taken into account.

Finally, women’s inclusion in parliament is developmental, based on the utilisation of skills and talents that women bring into politics.14 Thus the exclusion of women from the political system or any other work of life constitutes a waste of available resources, and the inclusion of women should maximise available resources and lead to improved outcomes.4 Supporters of this argument believe that women contribute a great deal of knowledge, skills and expertise and therefore their exclusion from public decision-making processes slows down the process of development. In fact for many developing countries such as Cameroon, women‘s political participation is often seen as a crucial step in achieving development and alleviating poverty.15 While the first and third arguments talk broadly of general and political between numbers, outcome and interest, the second focus on the representation of women’s interests or issues. This is the core concern for this study.

Conceptual and theoretical context

The discourse of women’s political representation is often articulated within the context of descriptive and substantive representation. Descriptive representation denotes the link between the characteristics of the representative and the represented. Representation is thus seen from the shared characteristics between the one representing and those being represented. Representation depends on the representative’s characteristics, on what she is or is like, on being something rather than doing something. The representative does not act for others; she stands for them, by virtue of correspondence or connection between them, a resemblance or reflection (Mansbridge, 1986, Kingdom, 1981). Adopting this into the theory of critical mass, and making reference to impact, the critical mass theorists (Childs and Krook, 2006) stipulates that women are unlikely to have an impact until they grow from a few token individuals into a considerable minority or critical mass of legislators. Assuming therefore that there is a linear relationship between numbers and outcomes and a precise although unknown tipping point at which feminized change occurs.16 A large minority can make a difference, even if still a minority.17 Thus, the critical mass theory alongside descriptive representation posits a connection between a number of women which is the input and the end product or action. The belief therefore is that if enough women are elected in the Cameroonian parliament to reach a “critical mass”, the result will be legislative transformation in favour of women’s agenda (Lovenduski et al 1989:115). The shortfall of this definition according to Pitkin is that it emphasizes the composition of a political institution rather than the activities of that institution. In this case, individuals cannot be held accountable for who they are but for what they have done.

Substantive representation on its part captures the relation between the representative and the represented. Here, the representative must be responsive to the represented.18 This could be achieved in two ways; making the representative a delegate with no independence or empowering the representative to act on their behalf. Feminist researchers (Celis et al, 2008) in a bit to conceptualize their research on women’s political representation concord with Pitkin’s claim that focus should be on what representatives do rather than on what they are. This is reechoed in the theory of the politics of presence. The politics of presence theory argues that the most important reason for promoting women’s inclusion and participation in parliament is that women are needed to speak for other women in those policy areas where they have a different experience and different interests from men as a group (Lovenduski and Norris 2004). It is claimed that shared experiences and their feminine nature mean that women as a group act differently from men as a group. The central argument of this school of thought lies in the common understanding that women share various life experiences because of the kind of social roles they tend to perform, which generally have an emphasis on their reproductive roles. In summary it is assumed that due to their particular life experiences in the home, work place and public sphere, women politicians prioritize and express different types of value, attitude, and policy priorities, such as greater concerns for child care, health or education, or a less conflictual and more collaborative political life.19

These feminist19 however explores Philips20 intuition that the sex of representatives matter to how they act. Though they agree that the main political actors to women’s substantive representation are likely women, they at the same time maintain that they should or must not be biologically female.21 Feminists at the same time overtly recognize women’s heterogeneity as a group, stating that there is no theoretical or empirical credibility to the idea that women share all or even particular experiences.19 As a result scholars make reference in terms of women having a higher likelihood of hitting the target in terms of acting for women even while admitting that female representatives are still shooting in the dark.19,20

In an analysis of the attitudinal and behavioral differences between men and women office holders19 feminists’ researchers found that men and women promote or advocate distinct policy priorities.22,23 Female parliamentarians often feel obliged to represent women5,24 recognize women’s interests25 and share the same opinion as female voters (Matoe Diaz, 2005) and women’s movement activists.26 Concerning their behavior, female parliamentarians differ from men in terms of setting the legislative agenda and proposing new bills that address women’s concerns (Bratton and ray, 2002; Childs, 2004). The presences also lead to changes in political discourse27 and shifts in parliamentary practices and working hours.28 However Celis et al.9 also note that the mere increase in the number of women elected (critical mass) does not always translate automatically to a critical act. This it is explained is impeded by political affiliation, institutional norms, legislative inexperience and the external political environment.9,29,30 In Uganda for example where it is known that women have already archived an almost 50/50 representation in parliament, women’s status is still remarkably lower than that of men on all counts in politics, the economy, and the socio cultural aspects. Feminized poverty, gender based violence and the generalized lack of respect and fulfillment of women’s rights seem to be the norm rather than the exception (Kirevu et al, 2013). Hence in this case a critical mass is not necessarily the sure way to make a feminist difference to politics and policy making.

What is important is critical actors, those individuals who initiate policy proposals on their own, who encourage others to promote policies favorable to women despite their numbers;9 not necessarily women. This Celis et al.9 explains and as developed by a second feminist literature are women’s movements and State agencies. These include women’s policy machineries (units charged with promoting women’s rights) such as ministries, commissions, offices, advisors to the status of women.31 who reflect women’s demands when advocating for social and economic policies that are beneficial to women as a group. MacBride32 finds that women’s policy agencies constitute effective links between women’s movement and the State through studies of various policy debates on abortion,32 domestic violence33 and political representation.34 Women’s interests are best defined through collective processes of interest articulation, rather than simply the perspective of a single legislator.33

However, the success of these agencies depend on their location and the resources of these agencies (Rai, 2003) the open/closed nature of the policy system, party in power at the time, unity and commitment of women’s movement to the issue in hand.32 Demonstrating examples of how the ruling parties rapidly set about consolidating the diverse and militant women’s movements, Tsikata (1997:393) demonstrates the situation of Ghana while Gaidzanwa (1992) portrays that of Zimbabwe and South Africa and Tripp (2000) that of Kenya. These authors reflect on how women’s movements were co-opted into the ruling party. With the merging of these women movements, political lines of difference were reduced to personality struggles and petty conflicts (Lewis, 2004). Tripp (2000) however goes further to emphasize the case of Uganda were women organizations were able to elude State co-option; a position that has generated the vigorous gender struggles in the country today (Lewis, 2004). Weldon33 therefore stipulate that these women’s policy agencies must have resources and authority and a degree of independence and they must not be in alliance with the State so that they may criticize the government.

From the above discussion it is clear that there is no simple consensus in the literature on the relationship between: the number of women in parliament and the representation of women’s interests, neither is there a clear relationship between women’s movement/civil society and female parliamentarians; increase in the percentage of women in parliament and decision making bodies; and changes that will enhance gender equality and women parliamentarians representing women’s interests because they share the same historical experiences. It is however the aim of this research to inquire if the above literature is applicable in the Cameroonian parliament. Does the number of women in parliament impact on gender related policies or does substantives representation have an effect on women’s inerests?

Section 1 (2) of the revised Cameroon Constitution of 18 January 1996, defines Cameroon as a democratic decentralized unitary State with a semi-presidential form of government, where state power is exercised between the President of the Republic and the Parliament (Section 4). According to the constitution, Cameroon has a bicameral parliament; the National Assembly and the Senate, but practises a unicameral parliament. A de facto single party system prevailed in Cameroon from 1966 to 1990, the year in which the Political Parties Act (Law No. 90/56 of 19 December 1990) was promulgated (UN, 1999).

The National Assembly or Cameroon's Parliament consists of 180 members of five year tenure. The current legislature (2007-2012) has twenty four women; twenty one from the Cameroon People’s Democratic Movement (CPDM) which is the ruling party, two from Democratic Union of Cameroon (UDC) and one from the Social Democratic Front (SDF). The political parties represented in the current legislature are: Cameroon People's Democratic Movement (CPDM) with one hundred and fifty three (153) seats, Social Democratic Front (SDF) with sixteen (16) seats, Democratic Union of Cameroon (UDC) with four (4) seats, National Union for Democracy and Progress (UNDP) with six (6) seats and Movement Progressive (MP) with one (1) seat (IPU, 2007). The single-member constituencies practice the “First Past the Post” electoral system and the multi-member constituencies practice “Party-List” electoral system (Parliament Archives).

The research is a descriptive survey. Eleven female parliamentarians were interviewed, one from the UDC party, one from the SDF, one former parliamentarian from the one party era and eight from the CPDM party. Semi-structured interviews were used in order to achieve what Holstein & Gubrium35 describes as getting access to people‘s ideas, thoughts and memories, in their own words, rather than in the words of the researcher. These semi-structured interviews with open-ended questions let the interview (process) develop as a guided conversation, according to the interests and wishes of the interviewee. This method of data collection was suitable for this research, which focused on female parliamentarians as it enabled them to feel free to speak about their personal experiences as female members serving in public life. Questions ranged from their participation in parliamentary structures that is their mandate, political party, position occupied in the National assembly and women’s level of participation in decision making bodies, sessions and meeting in the National Assembly. To their understanding of women’s issues, types of bills proposed to the National assembly, types of interests represented, their relationship with their fellow parliamentarians and the civil society especially their membership and positions in women’s movements amongst others. Female parliamentarians were also probed on their engagement with their constituency, other political parties within the National assembly and their challenges. Other questions included the role of institutions, political parties and the civil society in determining the legislative choice and behaviour of the parliamentarians amongst others.

The researcher was also able to obtain interviewees real views and beliefs. It was also necessary in achieving what Seidman36 describes as the desirability to have the participant reconstruct his or her experience within the topic under study, in this case avoiding any presumptions and focusing on what she terms as the personal experience of the participant.36 Interviews were transcribed and analysed. The names of the female Members of Parliament (MP) used in the analysis below are fictional due to ethical reasons.

Institutional structures and the substantive representation of women in the Cameroon parliament

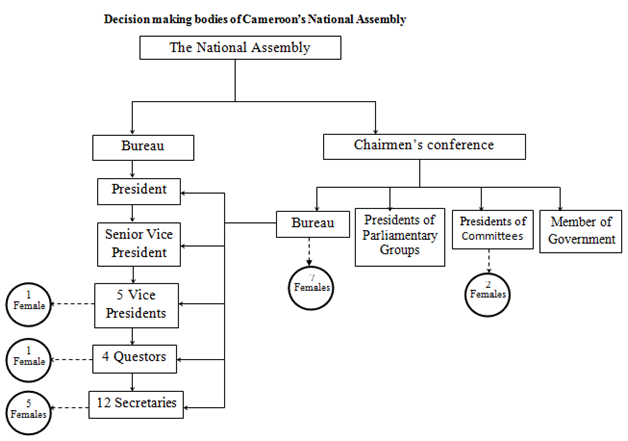

The components identified are, parliamentary structures and the state (political regime) for the activism of women‘s issues. All female MPs interviewed revealed that women are represented in each structure of the current legislature in the Cameroon parliament. The Bureau and the Chairmen’s Conference, which are the main decision making bodies consist of: the President, the Senior Vice President, Vice Presidents, Questors and Secretaries; and the Bureau, Presidents of Parliamentary Groups, Presidents of the nine Committees and a Member of Government, respectively. Within these structures, there are seven (7) women in the Bureau and nine (9) in the Chairmen’s Conference. Judging from the above, we realise that 18.9% of parliamentarians are in decision making bodies. From the proportion of members of parliament involved in decision making bodies, 26.5% are female MPs while 73.5% are male MPs. The adoption of bills, especially the Finance bill explains this vividly. Once the draft finance bill is tabled by the executive in parliament, the President of the House convenes the Bureau. It is later sent to the Chairmen’s Conference to check its constitutionality. Then, it is forwarded to the Finance and Budget Committee, headed by a woman for deliberations (Figure 1).

Based on the above procedure, we realise that women are represented at all levels of Parliamentary debates on the Finance Bill, which is the most important tool for project implementation and policy transformation. But, if one had to go by the critical mass theorists, it can be argued that the 26.5% of women in decision making bodies cannot transform politics. That is, this percentage cannot adequately stand for and act for women because they are not up to 30%. Honourable (Hon) Judith from the ruling party, in this light argued that “if more women were to be represented in parliament, then they will occupy more positions in decision making bodies, more than what we have today and will be able to forge issues concerning women”. However, the politics of presence theorists accepts this percentage (26.5); if, these female MPs can adequately act for women. But, Hon Susan from the CPDM contradicts this by saying. “Law makers tend to assume that all individuals are equal, with shared interests. This makes them fail to acknowledge the evident difference that stem from race, gender, age, ethnicity and location during budget deliberations”. They therefore ignore the fact that policies and budgets have different outcomes for different groups. However, if both numbers and gender awareness are considered, it was noted that the institutional structures plays a crucial role in the substantive representation of women in the Cameroon Parliament. As Busche37 argues, institutional competence is crucial for the attainment of substantive representation of women in parliament. As observed in the literature above, descriptive representation is necessary but not sufficient condition to achieve policy outcomes that favour women. Parliamentary structures and the political system must go hand in hand with a greater numerical presence of female MPs in order that they can substantively represent women‘s issues.

Cameroon operates a semi-presidential system where bills come concurrently from the executive and parliamentarians. In the domain of law,38 each of these powers can submit a bill for consideration by parliament; the Government member bills by the executive and the private member bills by parliamentarians. Female MPs can thus only table bills that address women issues through the private member bill. But, such bills are difficult to come by as most bills deliberated and adopted in parliament come from the executive. To confirm this, Hon Mary from the opposition party stated that, “you must take note that Cameroon runs a semi-presidential system and not a semi-parliamentary system. Consequently, it is difficult for us female parliamentarians to actually table bills that concern women in particular”. But when female MPs do table bills, for example the criminalisation of Female Genital Mutilation since 2007, it takes time for the bill to be adopted. This could either be due to inadequate lobbying by female MPs in parliament, or the descriptive representation of women which does not allow them to achieve a majority vote.

Empirical studies revealed that the role of political parties in determining the legislative choice and behaviour for party members is very strong. In fact, party discipline is paramount in a legislator’s entry and behaviour in parliament. The SDF party has a quota system in its constitution were it is believed that, 30% of women must be represented in each level of decision making. Be it in the party, appointed or elected positions. The CPDM on the other hand, does not have a quota system in its internal by laws. It however goes by the electoral code which stipulates that a list cannot be presented without a woman in it. Therefore, according to rules governing political parties, women must be a part of a list before it is accepted. However, from information collected from secondary data, it was realised that, the percentage of women in the multi-party Assembly, from 1992–2007 fell sharply. This is partly because of the small number of women nominated by political parties beginning with preliminaries and the pre–selection of candidates. Moreover, some political parties do not put women to head their lists. In 1992, out of 49 lists submitted by the CPDM, only four were headed by women. From the 46 lists submitted by the UNDP, two were headed by women. The MDR and the UPC had no women at the head of their lists (CEDAW, 1999).

It was also established that political parties have a great influence on attitudes and legislative behaviour of parliamentarians, both men and women. For example, the manifesto of SDF parliamentarians voted into office during the legislative elections in 2007 was more generic. There was nothing particular about women or their issues. While speaking with Honourable Peter, SDF National Executive Committee member, he said “…MPs from this party have to meet up with these manifestos while in parliament…” Female MPs therefore are restrained by this because they have an obligation to their party. They tend to be more involved in inter party politics than consolidate around women’s issues. All female parliamentarians of the ruling party interviewed were also of the opinion that they feel more inclined to the issues of their party than any other issues.

As a result, even if women were to attain the critical mass, they will still not be able to propose policies that are feminists oriented in Cameroon. Their mere presence in Parliament will not transform policies to suit women’s issues until the political system or regime is revised. Therefore, as Franceschet & Krook39,40 and Hon Mary opined, one should not disconnect the legislator from her legislative context in the analysis of substantive representation. This is because it will make us miss the critical link between women’s descriptive representation and legislative outcome.

Profile of female parliamentarians and substantive representation

Profile of female parliamentarians in this context include their age, educational level, professional background, political party and parliamentary experiences as these variables affect their substantive role. The current numbers of female MPs in Cameroon are well educated as none of them have below a University degree. Fifty five percent have acquired a Bachelor’s degree and 45% have a Post graduate Degree. Their educational level therefore allows them to actively participate in decision making, debates and make valuable contributions. All those interviewed were of the opinion that their educational level influences their contribution on issues during debates in sessions or committees. Hon Queenta, from the CPDM party emphasized that, “You can work better when you are a graduate with confidence”. Hon Linda, another CPDM MP also added that, “it is imperative because with at least a degree or its equivalent, an MP has a general knowledge of issues in all spheres which are very important during deliberations in sessions and in committees”. Their professional profile indicated that, prior to becoming parliamentarians; these women belonged to different professions. Female MPs had the following professions and belong to the following committees (Table 1).

| Firstname | Professional background prior to parliament |

Committee |

Educational planner |

Constitutional Law, Human Rights and Freedoms, Justice, Legislation, Standing Orders, and Administration |

|

Business woman |

Economic Affairs, planning and Regional Development |

|

General Manager |

Finance and Budget |

|

Civil Administrator |

Constitutional Law, Human Rights and Freedoms, Justice, Legislation, Standing Orders, and Administration |

|

Teaching |

Foreign Affairs and Cultural, Social and Family Affairs |

|

Accountant |

Constitutional Law, Human Rights and Freedoms, Justice, Legislation, Standing Orders, and Administration; |

|

Forest Exploiter |

Foreign Affairs |

|

Economist |

Cultural, Social and Family Affairs |

Table 1 Professional Background of female MPs and their respective Committees

Source: Information from field work, 2012.

One can conclude from Table 1 that, there is very little relationship between the professional experience of female MPs and the committee in which they serve. Since their professions have little or nothing to do with their committee. Article 17 of the Standing Orders of the National Assembly states among other things that each political group shall be entitled to the number of seats on each committee as is proportionate to its numerical strength in the National Assembly. According to this article therefore, membership into committees is based on political configuration. Furthermore, membership in a committee is just for a legislative year, so parliamentarians certainly might belong to different committees during their five years mandate. It thus follows that once elected into parliament, factors other than gender, professional experience or education influence women’s substantive participation. However, the level of education of a female MP will help her to be able to participate and deliberate in any committee at a point in time. Education, according to Hon Linda, “is imperative because with a University degree, an MP has a general knowledge of issues in all spheres which are very important during deliberations in sessions and in committees”. This makes it easier for the female MP to be able to understand the plight of their fellow women and forge for transformative policies if they so desire.

All the female MPs interviewed fall above the ages of 46. They all observed that their ages in parliament make them more focused and involved in parliamentary issues than otherwise. They asserted that since they are no longer nursing mothers, their triple role is reduced giving them more time to attend meetings, and assume responsibilities. Hon Pamela, the former female parliamentarian who served in parliament in her childbearing age noted that, “During my mandates in parliament, I had to shuttle between attending meetings and taking care of the babies. However, these aging MPs might tend to be more conservative and instead maintain the cultural norms and values that do not serve women’s interest in their society. For example, Hon Magdalene noted that the question of the payment of bride wealth was a serious problem in her constituency, but she argued that, “I cannot table a bill for the removal of bride wealth payment because I consider it a custom that has been practiced in my community for many generations. Trying to change such customs will be going against the traditions and customs of my people”. She therefore represented the past and not the present generation. In other words, the more these type of female MPs who are conservative, the less the possibilities to have them transform the existing cultural barriers against women.

As earlier noted, most of the female MPs in the legislature under study come from the ruling CPDM. Hon Sarah, one of these MPs pointed out that, “my party’s ideologies always dominate when taking certain decisions in parliament”. This reiterated the fact that female parliamentarians from constituencies which practice the party list system tend to be more loyal to their parties than issues concerning women and their constituencies. They therefore have to represent the interest of their party in order to ensure their position in the next elections. This is what Mansbridge41 terms delegated parliamentarians, who are more responsive to sanction and dependent on judgment. Hon Gladys, (CPDM) goes much further to stress this party loyalty in her preference for a male Presidential candidate over a female one. According to her, ‘I represent the interest of my party; for example, I will not vote a woman in a presidential election with a platform for the improvement of the conditions of women because I have a male candidate that represents my party and I can only vote for him”. This makes it difficult for some female parliamentarians to substantively represent the interest of women. This is because, they are more inclined to party discipline than on women’s issues.42

The female parliamentarians interviewed had different parliamentary experiences. Three were serving their first mandate, five were serving their second mandates and two were serving the third mandates. From their different point of interest of becoming a parliamentarian, it was noticed that experience does not really influence the substantive representation of female parliamentarians towards women’s issues. This is because all of them, especially those who had served more than one mandate said they became parliamentarians to serve their people and the general public and not women. There was no emphasis on women or their issues. This was especially emphasized by Hon Regina, who said “there is nothing like women’s interest, I have my electorates, and they are men and women as well as my political party so I do everything to please them”. Hon Elizabeth also added that “Is there anything like the role of female parliamentarians in impacting on women issues? There is nothing like male or female parliamentarians when it comes to activities performed in parliament. We are there to scrutinise bills tabled by the executive”. Looking at Section 15(2) of the revised 1996 constitution, one can say that these female parliamentarians are acting as per the constitution which requires them to represent the entire nation and not a section of the population. As Carroll1 rightly observes, they differ not only from men but also among themselves in their backgrounds, their political ideologies and their perception of their roles as public officeholders. Besides, Tremblay2 has argued that not all women are committed to the feminist cause, as they may simply not be feminists. This assertion therefore concur with Philips (1991, 65) that female parliamentarians have different interests and the party’s interests is always their top priority.43‒63

A greater majority of female parliamentarians are not members or do not associate with women movements. 90% of women interviewed do not belong to any women movement which has as goal to improve on the socio-economic and cultural situation of women in the society. Most of these parliamentarians belong to women organisations such as church groups and other social groups. The other 10% who belong to women’s movements do not actually utilise the resources of the group to the benefit of their mission in parliament. This was emphasized by Hon Mary who said ….though we are members of women’s groups which have as mission to fight for the right of women; I cannot really translate this mission into bills that can be tabled in parliament because as I said we are not given opportunities to table private member bills. Even when it is done like the bill on Female Genital Mutilation it is kept pending and nothing is said about it. Also is difficult for us because most often these movements do not have the required funds to network for support on issues they fight for. From the above it can be said that institutions set the parameters within which the representation of women is advanced and determine the degree to which there is a relationship between political position and policy effects. (Shireen, 2009). This is particularly evident in cases where the ruling party is strongly institutionalised ad entrenched in the population.

This paper set out to investigate the links between descriptive and substantive representation of women. It confirms that institutional competence and individual characteristics of female parliamentarians are critical factors that could enhance attention to women‘s issues in parliament. From the findings, there is sufficient ground to uphold that descriptive representation of women in the Cameroonian parliament is necessary, but not a sufficient condition for the substantive representation of women‘s issues. These findings also challenge the linear accounts of representative democracy found in much of literature on women and political representation, particularly the critical mass theories by demonstrating that beyond theoretical numbers, it takes specific actors and an enabling structural and institutional environment (political system) for political representatives to commit to an agenda of women‘s issues in parliament. Even if gender matters in terms of equal representation, it does not provide the guarantee that women will view their role as that of women‘s representatives. This is because women are not a homogenous group as held by the post-modern feminists.

Meintjes42 however, advises that gender mainstreaming must mean more than simply increasing descriptive representation that is, women who are integrated must nurture the political will for feminist ideas , and that links between parliamentarians and the women‘s movement and the civil society must be strengthened in order to achieve a gender transformation of politics.42 In other words, although it is important that both men and women are equally represented in politics, substantive representation by female political leaders also requires structural and institutional commitment to gender equality that goes beyond the politics of presence in both parliament and other institutional appointments. In addition to institutional structures, there is need to consolidate an active and influential feminist group both inside and outside parliament that has strong and sustained links to women‘s rights Non-Governmental Organisations in order to caucus around women‘s issues, create awareness about them in the community and effectively politicise them as part of a feminist claim.

None.

Author declared no conflicts of interest.

©2018 Fonjong, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.