eISSN: 2576-4470

Review Article Volume 3 Issue 6

Universidad de Quintana Roo, Estudios Políticos e Internacionales, Mexico

Correspondence: Miguel Angel Barrera Rojas, Universidad de Quintana Roo, Estudios Políticos e Internacionales, Mexico,

Received: October 26, 2019 | Published: November 26, 2019

Citation: Rojas MAB. Divergences in the definition of poverty in Mexico and Central America. Sociol Int J. 2019;3(6):454-460. DOI: 10.15406/sij.2019.03.00211

The number of poor people that a country reports in its national statistics depends largely on how poverty is operationalized. This undoubtedly generates divergence at the time of making a macro-level shared analysis, since when using totally different dimensions in each country, even if in Latin America the Unsatisfied Basic Needs method is used, data will be generated that are not necessarily homogenized. Hence, the objective of this document is to analyze the divergence in the definition of poverty in Mexico and Central America. For this, the construction of a matrix that explains the operationalization categories that each country in the study region makes about poverty was proposed. This matrix was nourished by a vast documentary review of the methodologies for measuring poverty in the countries of study. Among the most important results is that although it is true that the countries of study conform to the methodology of Unsatisfied Basic Needs, the categories that each country uses are different, thus generating a regional framing problem for the definition of poverty.

This paper intends to make a discussion about the conceptual and documentary operationalization of poverty in Mexico and Central American countries that belong to the Caribbean. That is, Mexico, Belize, Guatemala, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras and Panama. The objective of the foregoing is to analyze the divergence of the operationalization of the concept of poverty in this region of the planet. To do this, a thorough, intense and intense documentary review of all those documents and working papers was made where the federal governments of the countries of the study region show what they consider and define as poverty from their contexts. With this information, a matrix was built where the dimensions that all countries consider as basic to define and measure poverty are appreciated, and which are part of the methodology of Unsatisfied Basic Needs proposed by the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, and on the other hand, the dimensions that each government considers appropriate for its social, political and economic realities and contexts are also distinguished.

According to data from the UN 1 and ECLAC, 2 the data on extreme poverty in Latin America are alarming even though since the 2000s conditional cash transfer policies have been implemented. These figures, which are true and have full validity, also have a methodological problem. The way to measure extreme poverty in all the countries that make up the ECLAC database is different in almost all cases. For example, in the case of Mexico, a poor extreme is a person with incomes below what his methodology calls "Minimum welfare line" and with at least three of six deficiencies that the Mexican federal government considers as basic. While in some islands of the Caribbean, Puerto Rico, for example, the extreme poverty methodology conforms to the World Bank poverty line, that is, a person is considered poor if their income is less than a dollar with twenty-five cents a day On the other hand, in Central America, countries such as Costa Rica establish a minimum monetary parameter (2.75 usd per day) very different from that of Mexico (4.9 usd per day) or Puerto Rico (1.25 usd per day), even, Costa Rica also sets a Minimum caloric consumption line to determine extreme poverty. It follows from the above the academic interest in profiling this work that documents the way in which poverty is operationalized in the Caribbean-Central America region.

The issue of poverty in Latin America, but especially in Central America has already been addressed by Sojo 3 who discusses in an interesting way the difference in how exclusion is perceived between developed countries and Central America. Basically, as the author points out “it is not the same, in principle, to fight for social cohesion than to fight battles against hunger and poverty”. 3 In the work of Cañedo & Barragán 4 it is mentioned that poverty in the Mexico-Caribbean-Central America region is so marked and deep that it is necessary to completely rethink the capitalist model under which all the structural policies of the region are designed and how do the social and solidarity economy is considered as the best option. The reason for the above is due to the fact that according to the Cañedo & Barragán 4 and others like Ávila, 5 the forms of social, political and economic interaction of the Latin American peoples are more friendly with the social and solidarity economy in helping to build more equitable and egalitarian societies. In other works such as Von Gleich & Gálvez, 6 García & Argüello, 7, 8 Barrera, 9 Barrera, Sánchez, 10 the concern about poverty in the study region is notorious, especially in the indigenous population, as these authors agree, they are the most disadvantaged, precarious, marginalized and poor population. Thus, it can be established that there is an evident precoupation for analyzing and addressing poverty in the study region, however, there is no evidence of work such as the one presented here where the study is carried out from the methodological basis: operationalization.

Analyzing the divergence – convergence 11 of public problems is an issue that has been approached from the perspective of Framing, which is conceived in an integral and transversal way. In fact, Dekker and Schotten 12 mention that under this perspective “it is expected that framing (…) applies, in particular, to intractable policy disputes that are characterized by a multiplicity of frames, which imply different definitions of the situation of the problem, as well as different suggested political solutions”. Aruguete 13 and Entman 14 agree that framing is necessary when the analysis requires “Select and highlight some facets of events or problems and establish connections between them to promote a particular interpretation, evaluation and / or solution”. This takes up special emphasis if works such as Fernández, Barrera and Olvera 15 are reviewed, who discuss how to operationalize social policy in Mexico and Costa Rica and question whether it is necessary to adjust the common method of Basic Needs Unsatisfied in Latin America.

On operationalization, especially in matters related to social issues, authors such as Martínez and others 16 propose a broad historical and multidimensional analysis of the relevance of the use of multidimensional measures to explain the concept of social well-being, as well as the identification of factors that determine such well-being. This, according to the authors, will be decisive in the way in which poverty measurement and combat is carried out. On the other hand, Manfredi 17 makes a strong criticism of the fact that the operationalization and design of indicators, to measure well-being, is biased as to when they are raised from the agenda of developed countries and not from the needs of countries with less development, which results in inconclusive statistical results.

Now, on the issue of poverty, authors such as Orshanky 18 point out that the first problem that the economy faces when trying to operationalize this concept is that poverty “is a value judgment; or it is something that can be verified or demonstrated except by inference and suggestion. (...) the concept must be limited by the purpose for which this definition is to serve”. Which suggests asking who is poor? The answer to this is in two main ways: the one-dimensional vision (World Bank, 1992, 2001, 2004, 2013) and where multiple factors condition it. 19, 20

In Latin America, the definition of poverty that he used to try to homogenize the social policies of the area since the 1970s was that of Altimir 20 who defines it as “a situational syndrome in which underconsumption, malnutrition, are associated, the precarious conditions of the house, the low educational levels, the poor sanitary conditions, an unstable insertion in the productive apparatus or within the primitive strata of the same”. Even Oscar Altmir 20 himself warns that there is a risk that the definition and operationalization of poverty are “strongly influenced by the socio-economic context and by the general objectives of the social project in which anti-poverty policies are inserted” from each nation Hence the importance of rethinking to almost 40 years of Altmir's work the path that the Central American Caribbean region has taken individually in addressing poverty. 21

The operationalization of Altmir's concept of poverty resulted in the Unsatisfied Basic Needs model that the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) implemented for Latin America in the 1980s and is broken down as follows:

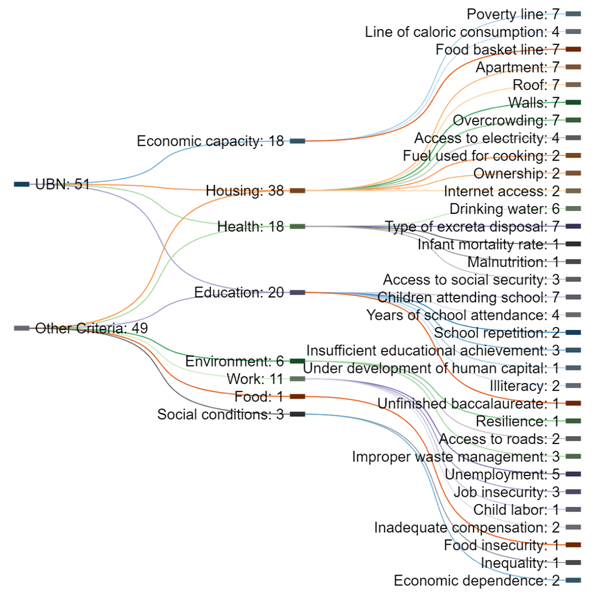

This UBN methodology should work as a common frame for the operationalization of the concept of poverty, however, as will be seen in the Sankey diagram and the regional matrix, this does not happen. This results in the fact that the data on poverty in the region are true and accurate by the methodology with which they are collected, but with different meaning given the operationalization that each country uses when disaggregating dimensions and subdimensions for poverty.

The following explains, by country, the way in which each one determines the criteria to which its statistical, policy evaluation or social development institutes will adjust, as the case may be, to measure poverty.

Honduras

According to the National Statistics Institute of Honduras, 25 the Permanent Survey of Multiple Purpose Homes (EPHPM) is used to measure poverty through the integrated Poverty Line (LP) method that was established at 2,890 lempiras per month per capita (UN, 2015), that is, 120.47 usd; and the Unsatisfied Basic Needs (NBI). In the case of this country, the dimensions of the NBI are four:

Nicaragua

In the case of Nicaragua, according to official data from the National Institute for Development Information, 26–28 poverty will be measured through two methodologies: the poverty line and that of the Unsatisfied Basic Needs.

The Poverty line in Nicaragua is broken down into two types, the extreme one that focuses on the daily caloric need of 2,268 calories (INIDE, 2009: 6) and has an approximate cost of 8,796 cordobas (275 usd) and is established with reference to two fundamental criteria, which are: the aggregate for consumption and the aggregate for income. The first refers to the accounting of all those foods that have been purchased by household members; the second is integrated by the consumption of non-food (goods and services): housing, Transportation, Education, Household equipment, Health, Education, Clothing and Daily use at home. 27

Costa Rica

The methodology used in Costa Rica to measure poverty is carried out through the measurement of NBI, under the name of the Multidimensional Poverty Index, which encompasses the needs that the State considers basic to live, frames them in various general indicators, which in turn have variables and indicators that give precision when collecting data.

According to the information of the National Survey of Income and Expenses (ENIGH) 2014, this methodology will be through five dimensions plus the poverty line:

For the poverty line, INEC 30, 31 reports that in Costa Rica that according to this method, “a poor household is one whose per capita income is less than or equal to the per capita cost of a basket of goods and services required for their subsistence”, 29 as of June 2018, the cost of the food basket that determines the poverty line is 40,060 colones, which in US dollars is equivalent to 82.59 usd. 31–33

Mexico

In the Official Gazette of the Federation (2016: 23) of June 16, the definition that the Mexican federal government will use for poverty measurement is established: three criteria

That is, people considered in multidimensional poverty are those whose income is not sufficient to cover goods and services to live fully, and is lacking in: “educational lag, access to health services, access to social security, quality and spaces of housing, basic services in housing and access to food. ”Official Gazette, 2010: 13-14).

In the case of the dimensions that make up the operationalization of poverty, the Mexican government uses the following criteria:

In addition to the criteria associated with the NBI, the Mexican government establishes two poverty lines: Minimum Welfare Line and Welfare Line. 35 In both cases, amounts are specified for rural and urban areas and the amount of each line varies each month. According to the Mexican government's own downloadable data, as of July 2018, the Minimum Welfare Line stood at $ 1,492.32 (74.6 usd) and the Welfare Line at $ 2,975.27 (148 usd) per month.

Panama

In the multidimensional poverty report of Panama of the Ministry of Economy and Finance (MEF) 36 of 2017 it was established that the unit of measurement of poverty is the home and that the method for the construction of indicators would be multidimensional, that is, the Poverty line to measure income and purchasing power of the food basket and five dimensions:

Regarding the poverty line, the MEF 37 makes a very important differentiation, since it has a basic food basket for the District of Panama and San Miguelito, and another for the urban rest of the country, having a cost of 302.65 and 278.03 balboas (the Balboas-US Dollar parity is 1 = 1) respectively as of February 2018, according to data from the MEF itself (2018: 11).

Belize

The measurement of poverty in Belize according to the National Plan to Combat Poverty (PRAP, 2014) is carried out through the Global Multidimensional Poverty Index plus the aggregate of vulnerability, which Carneiro38 well mentions. therefore, in Belize, given its conditions of being “a small open economy that is also extremely vulnerable to climate change”, the fight against poverty begins in the ability to overcome the negative externalities that can cause people to be vulnerable, the population I went into a state of poverty. In the case of this country, the dimensions are three and a poverty line:

The poverty line, determined by the basic basket is determined annually (PRAP, 2014: 19) and in 2014 it was estimated at $ 3,429 Belizean dollars, which in American dollars is equal to 142.2 usd per month

The latest versions (as of 2018) of the latest official documents by the federal governments of the study countries were reviewed in order to analyze the operationalization of poverty in the study region (Figure 1). The first criterion for separating operationalizations was whether poverty is measured only through income, as the World Bank suggests in its 1992 and 2001 report, or if it is done in a multidimensional manner. In the event that poverty is operationalized only through income, interest would be emphasized in the value in US dollars of the income line or of the food basket line. If poverty is operationalized in a multivariate way, it would be necessary to know whether it is done through the Unsatisfied Basic Needs (UBN) method or if dimensions were established according to the reality of each country. This is to establish if there is a divergence in operationalization and how marked it could be. Subsequently, from each dimension that according to the operationalization of poverty, the criteria that conform it were extracted. With all this information, a Sankey diagram was first constructed, and then a matrix to analyze the convergence in the operationalization of poverty in the study region. It is important to mention that the Sankey diagram is a graphic tool that was originally designed to illustrate the transfer of heat and energy flows, however, it has been adapted to the social sciences to graph the relationship of intensity and direction presented by categories-dimensions –subdimensions. 39, 40 In this case the information flows from left to right, that is, from the UBN to the indicators that appear on the far right with a number next to them, this number indicates the number of countries in the study region where the indicator is taken in account for the measurement of poverty (seven is the maximum possible) (Table 1) (Figure 2).

Source: own elaboration at sankeymatic.com

Figure 2 Sankey diagram for dimensions and sub dimensions of poverty in the study región

|

|

|

|

Belice |

Costa Rica |

Guatemala |

Honduras |

México |

Nicaragua |

Panamá |

|

Unsatisfied Basic Needs |

Economic capacity |

Poverty line |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Coloric consumption line |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Basic Food Basket cost (usd) |

142.2 |

82.59 |

112.57 |

120.47 |

148 |

275.31 |

302.65 |

||

|

Housing |

Flat housing |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ceiling |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Walls |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

overcrowding |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Sanitation |

Drinking water |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Type of excreta disposal |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Education |

School attendance of children |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Other criteria |

Health |

Infant mortality rate |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Malnutrition |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Access to social security |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Education |

Years of school attendance |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

School repetition |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Insufficient educational achievement |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Under development of human capital |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Illiteracy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Unfinished baccalaureate |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Housing |

Access to electricity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fuel used for cooking |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Ownership of assets |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Internet access |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Enviroment |

Resilience |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Road Access |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Improper handling of garbage |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Work |

unemployement |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Job insecurity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Child labor |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Inadequate compensation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Food |

Food insecurity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Social conditions |

Inequality |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Economic dependence |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: self made

Table 1 Dimensions to define and measure poverty in the study región

As can be seen both in the matrix and in the diagram, it is evident that there is a high divergence in the way in which the concept of poverty is operationalized in the study region. This implies that when making macro comparisons between the number of poor people from one country to another, there is a significant difference between data. A poor person in Mexico would not necessarily be a poor person in another country in Central America and vice versa.

This can be understood from two positions first, from the social constructions themselves based on the cultural, social, economic and even cultural specificities of each country, such as the case of the environment in countries with high vulnerability to hurricanes in coastal areas, or the infant mortality rates that more advanced countries such as Mexico and Costa Rica give as a public problem already solved; and, second, from the institutions of their governments. That is, there are countries with such a high degree of lag in the study region (even at the Caribbean level) that they do not have governmental instances or technical capacity to generate adequate data and methodologies as complex as those suggested by international instances.

And, although it is not denied the importance that the countries studied generate their own information on poverty, and that these can be compiled in databases such as those of ECLAC, the International Monetary Fund or the World Bank itself so that they are made In-depth analysis of the origins and consequences of poverty, the reality is that due to the operationalization that each country does on poverty, all the data that can be accessed have a different meaning. Come on, that a poverty figure in Mexico means something very different from a poverty figure in Panama or Belize, for example. And much of the difference in the origin of these differences is due, as illustrated in the diagram, to the additional indicators to the UBNs that each country uses, since in some cases they are indicators used by a single country. In that sense, it is of transcendental importance that the phenomenon of poverty is not addressed as part of a regional agenda, but as Aruguete 13 suggests, it should be considered to address it in a common frame of the phenomenon in question. It is necessary that the actors responsible for the generation and formulation of regional policies begin to generate efforts to generate more ad-hoc frames to the realities in which the countries find themselves with a view to making the information generated more homogeneous.

None.

The author declares there are no conflicts of interest.

None.

©2019 Rojas. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.