eISSN: 2576-4470

Review Article Volume 6 Issue 4

Depatment of religious studies, University of Bayernkolleg Schweinfurt, Germany

Correspondence: Ullrich Relebogile Kleinhempel, Depatment of religious studies, University of Bayernkolleg Schweinfurt, Germany

Received: July 07, 2022 | Published: July 18, 2022

Citation: Kleinhempel UR. Contemporary religiosity and consequences for the instruction of religion at upper secondary schools in Germany. Sociol Int J. 2022;6(4):182-184. DOI: 10.15406/sij.2022.06.00283

This is a pioneering article. It integrates findings about the composition of the field of religious and spiritual as well as atheistic convictions among the population of Germany, and among students in upper secondary classes of ‘protestant religion’ for teaching this subject. In particular, the strong presence of esoteric and Universalists convictions is taken note of. The article presents methodological and didactic consequences taken by the author, as also presented in professional training courses for colleagues in the field.

Keywords: religious instruction, didactics of religion, sociology of religion, didactics, empirical, surveys on distribution of contemporary religious, spiritual, and agnostic convictions for instruction of protestant religion at public, private secondary schools, creative, synthetic forms of learning in the field of religious instruction

In Germany Instruction in Religion or secular Ethics is a compulsory subject in schools, through all grades. The idea is that society needs a basis of values of its citizens and inhabitants. It is entrenched in the constitution.1 A choice of different denominations and religions is possible, if enough students enrol for the specific option, of Protestant, Roman Catholic, Christian Orthodox, Islamic or Jewish instruction – or of secular ethics.

In this brief article I argue that research on present religious and spiritual convictions in society, should be taken into consideration for the themes and for the didactics of religious instruction – as in Protestant Religion.

I base this on research about the distribution of religious and spiritual convictions and world views in several European countries.

Three orientations have been discerned:

In Germany all three are strongly represented, with the first comprising almost half the population and the latter a quarter each. In the meantime, the Christian segment has declined a bit. Observably both other segments have increased in public presence and strength. There is no progressive secularisation, as growth of atheist convictions, but rather a shift towards Esoteric and Universalist convictions. The proportion of self-professed atheists is higher in the middle-aged segment than among younger people.

I conducted research with questionnaires among my students at the Friedrich Fischer FOS-BOS Schweinfurt, upper secondary school, where I teach, that confirm this assessment. The questionnaire and the results are published in my detailed presentation on Academia.edu.2

This is pioneering work. Presently, Esotericism and Pan(en-)theism are widely regarded as ‘dangerous’, i. e. as competing religious-spiritual world views by both the Materialistic-Atheistic and the (official) Christian segments of society. Therefore, this study is pioneering work, with hardly any publications existing in the literature on religious instruction and the presence of Esotericism (and Pan(en)theism), apart from decades of polemics against ‘sectarianism’.

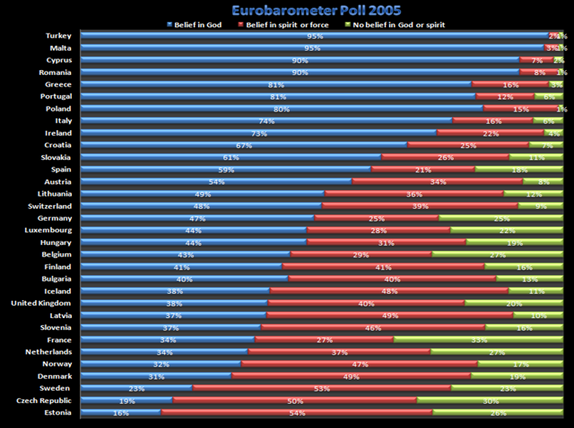

The Graph 1 with the distribution of results in the Europoll 2005 investigation is as follows:

Graph 1 European commission.

Source: European Commission. Eurobarometer - Social values, Science andTechnology. Fieldwork: January - February 2005. Special Eurobarometer 225, Directorate General97 Press and Communication. 2005. 9 p.

(A survey conducted some years ago in the course for Catholic Religion and in the course for Secular Ethics revealed results that do not deviate too strongly. This may in part be due to the fact that Muslims usually choose the course Secular Ethics, for lack of a course in Islam, at most schools.)

In my survey in the Protestant course, Spiritualistic and Pan (en-)theistic convictions are quite strongly present. Another finding is that a Naturalistic world view is by far not dominant but exists besides esoteric and spiritualistic world views (of “extended naturalism”).3

Consequences for instruction of protestant religion at upper secondary schools

Didactical consequences

In the first term of grade 12, I present the basic forms present in the field, as described above. These are categorised as:

The students are then asked to choose one of these six forms as their favourite. Groups of 4-6 students are formed. These groups are given the task to research a fictitious, but credibly‚ real‘ community of the specific religious, spiritual or philosophical conviction that the chose.

A catalogue of some 20 features is proved to them. (The questionnaire is available, in German.4 These comprise; roles, origins of the religious /spiritual teaching, specialists, sacred places, shrines, rites, calendar and festivals, roles of women and men, initiations, hierarchy, forms of communication with the transcendent, values, revelations, visions of the past and the future, the structure of time, divination, symbols, sacraments, observances, etc.

The students are asked to create a presentation. In it, their discovery is to be told. Their religious /spiritual community is to be presented in a way, that its life and spirit become conveyed vividly, so that it can be shared by the audience in the class.

To the group presentation, by power point, ritual elements, performances, and other forms of practice should be added. The groups should‚ re-present their community credibly.

They should convey what is valuable and interesting about the (fictitious) community they present. What follows is mostly an inspired and vivacious voyage of discovery. The students are given six weeks to research and to work out their presentation.

The role of the teacher is to serve as facilitator, and to counsel where obstacles or questions arise. The students are told to do research on existing religions or spiritual communities of their specific type, but that they should sternly avoid to copy. If they pick up ideas or features of the research, they should integrate them according to the character and spirit of their own community.

Sometimes groups complain, in the beginning, that they have no idea, of what to invent. They are told that ‚religion is never a matter of invention, but of inspiration!. They should wait for the spark of inspiration, in the way that a composer or a literary author does. It usually works. The students are often impressed by the inspiration that finally comes, and by their process of working it out. This becomes an‚ initiatory voyage of discovery, and of synthetic learning, that involves them intrinsically. The presentations take about 45 minutes each.

In the review, at the end of the year, the students regularly report that this was a most exciting and inspiring experience, that included intensive group experiences, sharing and reflecting their inspirations, ideas, research findings, and of systematising their results and of developing creative means of presentations, as by rituals.

In this way, the ground is laid for the individual assignments of research on historical and present forms of religion and spirituality, that they have to work out, to an individual presentation of research, in the second half of the school year. Both presentations are the basis for their marks in the respective terms. Thus, continuity, and changes of forms of work are provided throughout the year.

Topics for the individual presentations are from the following categories:

These vastly differing themes yet create a kaleidoscope, in conspectus, by the end of the year. The different categories provide pathways of access to the transcendent and divine, in widely diverse points of access. Similarities and differences can be observed and are discussed.

In this way, findings in sociology of religion, of science of religion and history of culture, can be fruitfully applied in public education. It is the task and challenge of a teacher to be well informed about these forms and developments, so as to capable of guiding the students carefully and knowledgably through their research.

As to didactics: Students embark on researching and (-re-)constructing a religious or spiritual community from ‘within’, involving their faculties of imagination, of systematization, of aisthesis, and of creative expression. This holistic experience is greatly enjoyed, in most cases.

It provides an experiential and intellectual access to the field, that is intellectually reflected and shared by the group in a common process, that includes the audience in the presentations. The methods and results in detail remain to be worked out for a future publication. This presentation – at a day for study for teachers of religion at secondary schools, in Schweinfurt, as part of their professional further training - was well received. This article is based on it and unfolds its consequences for religious instruction, as showed here in brief.

1Bundesministerium der Justiz /ed.)Grundgesetz für die Bundesrepublik Deutschland Art 7“.

2Kleinhempel Ullrich R.Vortrag: Zeitgenössische Religiosität und Folgen für den Religionsunterricht" (presentation), Schweinfurt; 2016.

3Kleinhempel Ullrich R."Extended Naturalism": Dis-entangling questions of the boundaries of reality from religious perceptions and interpretation of experience. Presentation at the conference: Wissenschaftlichkeit und Normativität in der Religionswissenschaft – Religionswissenschaft als Akteurin im öffentlichen Religionsdiskurs [Science and Normativity in Science of Religion – Science of Religion as Agent in Public Discourse on Religion] of the Deutsche Vereinigung für Religionswissenschaft, DVRW) - Arbeitskreis Mittelbau und Akademischer Nachwuchs, [German Association for Science of Religion]. University of Potsdam; 2018. p. 20-22.

4Kleinhempel Ullrich R. Vortrag: Zeitgenössische Religiosität und Folgen für den Religionsunterricht“ .

None.

There are no conflicting interests declared by the authors.

None.

©2022 Kleinhempel. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.