eISSN: 2576-4470

Research Article Special Issue Business Economics

USA

Correspondence: Yvonne Latrese, USA

Received: May 30, 2018 | Published: December 31, 2018

Citation: Latrese Y. A look through the sweat & years: an African-American family’s contribution to American economic & business culture. Sociol Int J. 2018;2(6):820-825. DOI: 10.15406/sij.2018.02.00142

The culture of our country manifests itself in everything that we do, whether spoken or unspoken. American culture is a diverse component of historical, literary, theatrical, political and popular cultural aspects. These aspects of American culture have led way to significant events and institutions which have shaped our American values. The postbellum years, employment, institutionalization and education were all important structures which make up a momentous portion of America’s heritage. America’s rich, assorted, existence is one filled with many stories. The Europeans had great influence over early Americans but they struggled with what was familiar and tried desperately to attain an identity of their own. Throughout this struggle many stories were born. The story of the African American family unit was one with a uniqueness of its own. My family’s story is one that is truly American and encompasses pure American values.

Keywords: african-american, census, slave, tennessee, coal, iron, railroad, convict lease, coal miners, sanitariums, cleveland state hospital, rosenwald, mayo-underwood, lobotomy

Throughout America’s cultural timeline, my maternal family, the Sweatt’s were impacted as a result of American culture. The stories that these people lived to tell were very different from the stories of other Americans. The African American or rather the “black” family did not have the same experience as the white, Indian or German family. The black family had a story all their own. The Sweatt family was no different. American culture influenced the Sweatts and dictated their actions. African Americans have played a major role in the shaping of American culture and my maternal lineage is present in significant events throughout the process.

The history of the black family is one that has to be pieced together. The United States Federal Census reports aide a great deal in fitting the pieces together. The census is performed by the United States Census Bureauevery ten years. The first census after the American Revolution was taken in 1790 under Secretary of StateThomas Jefferson. There have been twenty one federal censuses since 1790. The last national census was held in 2000, and the next census is scheduled for 2010. My research utilizing the census reports takes me back to the 1800’s when slavery was still a major institution in America.

The seventh Census was taken June 1, 1850. The 1850 census was a landmark year in American census-taking. It was the first year in which the census bureau attempted to count every member of every household, including women, children and slaves. Accordingly, the first slave schedules were produced in 1850. In 1870 (the first census following the Civil War and emancipation), African Americans were enumerated just like all others. Slave schedules were no longer used and each person was listed.1 Prior to 1870, census records had only recorded the name of the head of the household and utilized broad groupings to list other household members, (three children under age five, one woman between the age of 35 and 40, etc.). The history of African Americans in the United States began in 1619 when a Dutch ship brought the first slaves from Africa to the shores of North America. Of all ethnic groups, African Americans were the only ones to arrive on America’s shores against their will. No one knows for sure how or when my first maternal ancestor came to America but I do know that they were enslaved.

Frank Sweatt was born in 1853 in Tennessee.1 At the time my maternal great-great-great grandfather was born, his parents were slaves. Tennessee was a slave holding state and Frank was born into slavery. Although, slavery was abolished with the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment on December 6, 1865 it did not go away quietly or without traces of what the institution meant to African Americans. The 1870 census lists Frank Sweatt’s occupation as a farm laborer. He was a member of a household headed by a white man, James Morton. More than likely, James Morton had been a slave master before the civil war and Frank, along with family members; Rachael Sweatt (aged 28) and Lee Sweatt (aged 6) were probably once owned by Morton or a family not far from Morton. During the postbellum years, it was not uncommon for blacks to continue to work farm land for white families. This was due to the major uncertainty in terms of the reorganization of agriculture across the southern states.

The year 1877 was pivotal in America’s history and to Frank Sweatt. Frank Sweatt became a proud father in 1877 and for America the year marked the end of the “Reconstruction” period (the period between the end of the Civil War in 1865 to the final withdrawal of Federal troops from the south).2 Although all southern states were faced with major economic, political, land distribution and agricultural issues, Tennessee was faced with additional problems. Tennessee had chosen to secede from the Union during the Civil War and join the Confederate States of America (along with 10 other southern states). After the war, Tennessee was concerned with their re-entry into the Union and was the first of the seceding states to be readmitted on July 24, 1866.2

Economically, the Civil War had a devastating impact on Tennessee. The physical destruction of left behind from the war and the long-term effects of the end of slavery had to be addressed by the state (Reconstruction). All across the state, military veterans returned home to find ruined buildings and land, unkempt animals and low food supplies. “A congressional investigating committee… estimated [Tennessee’s] non-slave property losses at approximately $89million, or just under one-third of the total value of non-slave property in [the state] when the war began” (Reconstruction). On top of the overall economic devastation suffered at the state level, slave owners suffered major economic losses due to the emancipation of the slaves. Emancipation caused a redistribution of wealth from the slave owners to the former slaves, “who now for the first time legally owned their own persons” (Alexander). However, the newly acquired “wealth” was not appropriately acted upon by the former slaves.

During the Reconstruction period, freedmen attempted to buy their own farmland and secure as much independence as possible from their slave masters. This was not a reality for many. The obstacles faced by the freedmen coupled with the labor shortage for the white man led to more bitterness among the races. The move out of the Reconstruction period took America from an agricultural and trade economy (based on African American labor) straight into the industrialism or the Gilded Age.1 The Gilded Age for Frank Sweatt was his ticket to leave the strenuous farm laboring work. According to family records, Frank Sweatt became a proprietor of a boarding house and he was later mobilized to Europe during World War I.

Lindsey Sweatt, my maternal great-great grandfather was born on December 11, 1877 in Jacksboro, Tennessee (according to information from the 1870 United States Census). Lindsey was born to former slaves and was raised with common values such as honesty, integrity and a good work ethic. During the postbellum years, Lindsey along with most other black men painstakingly sought honest work. Lindsey found work as a coal miner with the Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Company.

The Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Company (TCI) was in existence for 100years (from 1852 until 1952). TCI was a major American company which provided a substantial economic base for the country during its lifespan. The steel manufacturer held interests in all major American economic industries of the time. TCI originated in Tennessee but opened new headquarters in Birmingham, Alabama in 1895 (a great-great uncle named Van Dyke Neal worked for TCI in Birmingham during the 1920s and 1930s and other family members found work with the company as blasters producing steel). The mining company was initially established in order to capitalize on Tennessee’s abundant coal reserves and the insurgence of railroad operations but the company soon found Alabama’s high-phosphorous ore more profitable. This realization led to the abandonment of Tennessee altogether and a monopolization of the surrounding areas of Birmingham. By 1899, TCI owned the towns of Ensley and Fairfield, Alabama.

It was common practice for coal mining companies, during the early twentieth century, to own the towns that coal miners lived and worked in. These company-owned towns were called “coal camps” (Philpot). In a coal camp, the company owned all the properties, houses and everything associated with the camp. TCI even built company owned private rail ways to transport their coal between the coal mines and the places they serviced. The wages were meager and were used to purchase necessities at the company owned general store. Often times the workers were paid in “scrips” which was tender that was only good within the camps (Philpot). Coal camps were segregated and “the African-Americans … were worse off than the white people” (Philpot). The blacks lived in separate camps and discrimination was commonplace.

The 1890 United States Census indicates that African-Americans made up 46.2percent of the overall coal miners. From the end of nineteenth century until the 1930s, African-Americans made up about half of all coal miners and of that half, 90% were convict miners. After the Civil War (1861-1865) southern states leased convicts to private industries for forced labor. “Slavery in the mines did not end after the war in 1865” (Philpot). Conditions in the convict mines were horrendous. The convicts were not trained and as a result many perished.

The convict lease system was the brainchild of the government officials. In an attempt to lower the cost of coal, from the late 1860s to the 1890s, convicts held by the State were leased to mining companies to do the work of miners. The rights to convicts were granted to a select number of coal companies (TCI was one of them). “In 1888, TCI negotiated a 10year contract that entitled it to all able-bodied state prisoners [in Alabama]”.3 TCI paid the state of Alabama monthly subsidies for each prisoner. The increased revenue helped the State lower the debt incurred from the surge in railroad expansion during the 1850s. TCI was a leader in leasing convicts for mining, because it kept labor costs down and filled the mines with a steady supply of workers. The majority of the leased convicts were blacks.

Not everyone was happy with the convict lease system. Local free-white miners did not go along with the labor system. It was not long before white miners, realizing the impact leased convicts had upon their wages, struck for higher earnings and the removal of the leased convict miners. These objections led to labor disputes between the free workers and management. But to the surprise of no one, management prevailed. Violence eventually erupted in retaliation against convict labor in the mines. In July 1891, three hundred “free” miners (both black and white) armed with militia, freed convicts from TCI’s facility located in Coal Creek Valley (Briceville, Tennessee). A week later 1500 miners returned to free more convicts. The convict lease system was finally abolished in 1892 but, a substitute system was found in the form of a new penitentiary (Brushy Mountain State Prison est. 1898) in which the prisoners would mine coal for the state (Jones).

In 1911, an explosion at a dilapidated TCI mine killed 123 African-Americans county prisoners.3 The tragedy led to more protest against the penal system’s use of prisoners in the mines. Finally, in 1912 TCI (under new management) declared that they would only employ free workers in their mines. Although TCI withdrew from the prison mining system, the practice continued. “In 1912, prison mining brought in a sum of more than $1 million…” (Adamson). Prison mining ended in 1928 after many incidents of abuse, torture, death and investigations. Alabama was the last state in the nation to abolish convict leasing altogether.

In addition to inhumane treatment by the company owners and management, coal miners were forced to work in unsafe conditions. "Employees in coal mining are more likely to be killed or to incur a non-fatal injury or illness, and their injuries are more likely to be severe than workers in private industry as a whole" (Butcher). Throughout American culture there are parts of society that have struggled with hardships; coal miners are part of that whole. Coal mining was hard work. During the nineteenth and early twentieth century, a considerable amount of mining was done by hand and safety was of little concern. The companies were notorious for overlooking safety in favor of profits. Black Lung Disease (occupational lung disease caused by inhaling dust) was prevalent and large amounts of coal miners were stricken with the disease.

Miners worked in conditions with high water, falling rock, dangerous gases, explosives and faulty light devices. Unrealistic quotas were enforced by officials and this added pressure to the miners’ already unsafe working environment. The emergence of the labor unions helped improve working conditions for miners. It was the practice of TCI to maintain low wages and limited unionization. The influence of the union made life better for all coal miners. The United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) was formed and after passage of the National Recovery Act(part of President Roosevelt’s New Deal aimed at stimulating the economy after the Great Depression) in 1933, organizers spread out throughout the United States to organize all coal miners. TCI was eventually forced to comply with union demands and follow such as adhering to an eight hour work day.

The Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Company had a very major impact on the history and culture of America. The lifespan of TCI from 1852 until it ceased to exist as a separate corporation in 1952 was full of issues that represented the happenings in America. My great-great grandfather, Lindsay Sweatt was in search of a job. All he knew was the fact that he had found work. Little did Lindsay Sweatt know that the work he found was significant. Coal mining was one of the leading economic industries in America, TCI laid ground work for unethical employment practices to be outlawed and the suffrage of the workers and the detriment to their health lead to the passage of benefits for Black Lung sufferers and their widows (1969).

Over the course of America’s history, psychiatric hospitals and the treatment of disabled persons has not always been the respected and law abiding way that it is today. Today, disabled persons are protected by the Americans with Disabilities Act and psychiatric hospitals are closely governed. People are not institutionalized against their will and many conditions are regulated with medication. This was not always the case in our great country. My maternal great grandfather,4 Ponolia Sweatt was committed involuntarily by his wife to an insane asylum. Commonly referred to as sanatoriums, lunatic hospitals or state hospitals, the placement into one of these places represented a darker period in mental health care, with involuntary incarceration, barbaric and ineffective treatments, and abuse of patients.

Some historic sanitariums were state-run tuberculosis hospitals, and a few were actually insane asylums.4 Ponolia Sweatt was committed to the Cleveland State Hospital sometime during the 1940s. The psychiatric facility was a state supported hospital originally known as the Northern Lunatic Asylum and was established in Ohio during the 1850s. The land that the hospital was built on was donated by the family of James A. Garfield (Garfield later became the 20th President of the United States).5 The intention of the asylum was to provide a place where disturbed persons could live healthy and learn moral living habits outside of jails and poorhouses. However, historical documentation and accounts have proved that this was far from the ideal living conditions for those placed there. Asylums where known to seclude, cuff, strap, straitjacket and confine persons to cribs. The institutions were inadequately staffed and often over crowed.

From 1942 to 1947, people were assigned to psychiatric hospitals under Civilian Public Service. Civilian Public Service (CPS) provided conscientious objectors in the United States an alternative to military service during World War II. From 1941 to 1947, nearly 12,000 draftees, willing to serve their country in some capacity but unwilling to do any type of military service, performed work of national importance for the United States.6 The CPS was fruitful in exposing abuses throughout the psychiatric care system and was instrumental in psychiatric reforms of the 1940s and 1950s. In 1946 an investigation into the Cleveland State Hospital, initiated by the Cleveland Press (in publication from 1878 until 1982) and the Cleveland Mental Health Association uncovered brutality, criminal neglect and squalid conditions. As a result of the investigation, CPS Unit No. 69 was assigned to the Cleveland State Hospital and was given complete charge of the male infirmary, housing approximately 365 “infirm and untidy mental patients.6

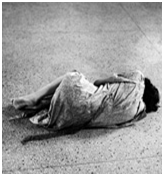

On May 6, 1946, Life magazine published "Bedlam 1946," an exposé of two state hospitals: one of which was Cleveland State Hospital. The Bedlam reference was one that was once used to refer to all psychiatric hospitals (Bedlam was the first noted hospital for the mentally ill in Europe during the 1700s and became notorious for its neglectful care). “To a country shaken by recent revelations of Nazi atrocities, the pictures [in the article] were deeply affecting”.7 The Ohio grand jury who presided over the investigation into the conditions at Cleveland State Hospital, where several patients had died after being beaten with belts, key rings, and metal-plated shoes, summed up the state of affairs: "The atmosphere reeks with the false notion that the mentally ill are criminals and subhumans who should be denied all human rights…"(Figure 1).7

The “Bedlam 1946” article went so far as to describe the starvation diets that the patients were subjected to while the staff enjoyed the best food. Court records uncovered during the grand jury’s proceedings documented scores of deaths and hundreds of instances of abuse which fell just short of manslaughter. It was noted that the ratio of physicians, nurses and attendants found in the Cleveland State Hospital was “far below even the minimum standards set by state rules”.7The asylum was filled with more patients than they could physically house and the conditions were not due to the impending war. The conditions had progressively deteriorated over the decades. “Restraints, seclusion and the constant drugging of patients became essential. . .”8

[At the Cleveland State Hospital] An attendant and I were sitting on the porch watching the patients. Somebody came along sweeping and the attendant yelled at a patient to get up off the bench so that the worker-patient could sweep. But the patient did not move. The attendant jumped up with an inch-wide restraining strap and began to beat the patient in the face and on top of the head. “Get the hell up . . .!” It was a few minutes – a few horrible ones for the patient – before the attendant discovered that he was strapped around the middle to the bench and could not get up.8

Another effort of CPS, namely the Mental Hygiene Project, became the National Mental Health Foundation. Initially skeptical about the value of Civilian Public Service, Eleanor Roosevelt eventually became a sponsor of the National Mental Health Foundation and actively inspired other prominent citizens to join her in advancing the organization's objectives of reform and humane treatment of patients.

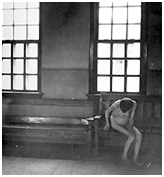

First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt was not the only person who responded to the plight of the mentally ill. The crisis in state mental hospitals motivated Dr. Walter Freeman to devise a simple version of the lobotomy procedure, one that could be used on a mass scale.9 Freeman, a psychiatrist and neurologist, began a wave of psychiatric surgery that was used on 40,000 to 50,000 Americans between 1936 and the late 1950s. His simplified technique of trans-orbital lobotomy was such a breeze that he could teach it in a day or two to state-hospital psychiatrists who, like himself, had no qualifications in surgery.9 The procedure, which his father, Walter J. Freeman, popularized and perfected, involved first, knocking the patient unconscious with two or three jolts of electricity from an electroshock therapy machine. After the convulsions subsided and the patient lay insensate, Walter Freeman lifted the patient's eyelid and inserted an ice pick-like instrument called a leucotome through a tear duct. The leucotome was then pushed into the frontal lobe of the patient's brain, and then the brain was “scraped” with the sharp tip.9 Freeman argued that lobotomy was the answer because it severed neural connections between the frontal lobes of the brain and the thalamus, which he characterized as the seat of human emotion. According to Freeman, mentally ill people were too self-aware which resulted in overactive emotions and obsession about their problems. By the time Freeman died in 1972 his advocacy for the use of lobotomies on the mentally ill had been discredited (Figure 2).

By the mid-1940s, treatment of the mentally ill took a new turn, with the introduction of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) and insulin shock therapy, and the use of frontal lobotomy. In modern times, insulin shock therapy and lobotomies are viewed as being almost as barbaric as the Bedlam "treatments" though in their own context, they were seen as the first options which produced any noticeable effect on the patients. It is not clear what treatments my great grandfather, Ponolia Sweatt, was subjected to but it is a known fact that he was placed in the Cleveland State Hospital at a very sad and controversial time in American history and remained institutionalized until his death on November 29, 1987. The fight for the humane treatment of the mentally ill population has been a long drawn out process. The political and public awareness of the importance of human life is apparent thorough out history and the efforts to correct the wrongs of a group that was once voiceless have made great strides.

The ticket to complete freedom for African Americans was education. My great-great aunt Lucy Sweatt (1897-1999) realized this at an early age. While her grandfather, Frank Sweatt was out toiling agricultural farmland and her father, Lindsey Sweatt was mining coal, Lucy was learning how to read and write. The United States census of 1900 shows that Annie Sweatt (Lucy’s mother) was educated. Annie was able to read and write and in turn she taught her daughter. Lucy went on to use those skills to become a teacher. By 1930, Lucy was teaching in a public school in Lynch, Kentucky. Sometime during the 1930s Lucy moved to Frankfurt where she began teaching at Mayo-Underwood public school.

The move to Frankfurt and the experiences at Mayo-Underwood were priceless for Lucy. My great-great aunt Lucy became part of history in the state of Kentucky. During the years after slavery, reconstruction and the gilded age, race relations in southern states were still uneasy. Kentucky remained one of the states which enforced segregated schools. Since the state was segregated, black schools could not compete in the state’s high school athletic tournaments. As an answer to this problem, black schools in the state banded together and created the Kentucky High School Athletic League in 1932.10 The league was created in order to give the students attending black schools an opportunity to compete at the state level.

Kentucky’s separate and unequal school system left the black schools in the state impoverished and backwards. During the Reconstruction years, few black public schools were founded in Kentucky, most of the growth happened after World War I. In the beginning, the schools provided only two years of instruction and it was not until the late 1920s and early 1930s that the secondary schools for blacks went on to provide four years of instruction like white schools. It was common knowledge that the black schools did not have adequate state support and were thus unable to financially support an interscholastic athletic program. The schools themselves were small, inadequately furnished and did not have amenities like gyms. During the 1920s this changed. A northern philanthropist, Julius Rosenwald (head of Sears-Roebuck) donated money to black schools in the south. “Rosenwald contributed to the construction of 5,357 schools, shops, and teachers’ home in black areas of the Southern states”.10 At least five Kentucky high schools in black areas were named after Rosenwald.

With money problems aside, the black public schools in Kentucky were able to focus on education and recreational sports. The Kentucky High School Athletic League began to pick up momentum. The first schools to form basketball teams were Louisville and Hopkinsville, Kentucky. There were so few black schools in Kentucky with sports programs that the Lincoln basketball team has to compete with teams in Illinois and Missouri.10 Less than twenty black public schools in Kentucky were competing against one another. After the endowments from Rosenwald, more and more schools began to engage in competition. The fast growth was due to an increase in support of educating blacks. Major race supporters like, Booker T. Washington, W.E.B. DuBois and Ida Wells-Barnett were on the scene telling blacks how important education was to the betterment of the people.

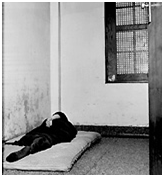

Once the Kentucky High School Athletic League was sufficiently engaged, the league began to hold competitions. Competitions were held in three sports; basketball, football and track. Basketball was the only sport that went on to state championship games. The first championship game was between Central (Louisville, KY) and Fee (Maysville, KY) in 1932. The state final was held at the Kentucky State College gym in Frankfort.10 The two competing teams advanced to the finals based on the best 16 teams from around the state. In 1932 the best teams were Louisville Central, Mayo-Underwood in Frankfurt (where my aunt Lucy taught) and Douglass in Lexington (Figure 3).10

Mayo-Underwood made it to the state championship game in 1933 and defeated Fee. This was an exciting and new time for school officials, students and parents. Mayo-Underwood went on to win the state championship again in 1941, beating Lincoln Institute (Lincoln Ridge, KY).

During the formative years, the black schools were complacent with competing at the state level. Black school in Kentucky had little success in the national tournaments. It was not until later that black schools became a significant presence in national competition. One early success, from the Kentucky High School Athletic League, was that of Madison Rosenwald. The school won at the state level in 1936 then went on to win the Southern Interscholastic Basketball Tournament, held for black schools by Tuskegee Institute (Booker T. Washington). Madison Rosenwald won state championship games in 1935, 1936, 1945 and 1946.10

Other notable successes in the Kentucky Athletic League were Lincoln Institute in Lincoln Ridge and Horse Cave. Lincoln Institute was a small boarding school that won state championship titles in 1938, 1939 and 1942. Horse Cave was one a small poor rural school that surprisingly became a basketball powerhouse. The school opened in 1930 and did not become a four-year institution until 1937. The principal and coach, Newton S. Thomas, did not know much about basketball, so he went to basketball clinics conducted by the renowned basketball coach, Adolph Rupp (the third winningest coach after Bobby Knight and Dean Smith).10 By 1943, Thomas apparently learned enough from Adolph Rupp to lead Horse Cave to third in the state. “Then in 1944 and 1945, Horse Cave took back to back state titles. The 1944 team went undefeated and featured future Harlem Globetrotters player Carl Helem”.10 Thomas did all of this winning in extremely poor conditions, Horse Cave was so impoverished the school did not have an indoor basketball court. The team practiced and played on a hand-built court constructed out of plywood backboards and a pounded dirt surface (Figure 4).

Being a teacher for Lucy Sweatt during some of America’s most crucial years for blacks was a triumph in itself. Not only did Lucy become a teacher, she became part of history in Kentucky. As integration made its way to Kentucky in the late 1950s, the Kentucky High School Athletic League began to rapidly lose members. Many all-black schools were closed and other members left to join the previously all-white Kentucky State High School Athletic Association (KSHSAA). The Kentucky High School Athletic League eventually disbanded after the 1957 season. By the time integration was completed during the 1960s, few original schools from the league had survived.11

America’s culture has been shaped by many events throughout the years. The people involved with those events help us take the history out of the text book and put a face on it. It was truly an amazing discovery when I found that my ancestors had a significant place in this country’s greatness. At times there were significant prices to be paid but the ultimate outcome was rich. The diversity, the stories and the triumphs are overwhelmingly unique. The antebellum years were filled with confusion but Frank Sweatt was able to persevere and still love his country enough to fight valiantly for it during World War I. Lindsay Sweatt was on the ground floor (or under it) of America’s richest economic industries while coal mining in Tennessee and Alabama. Ponolia Sweatt tragically ended up suffering abuse at the hands of an institutional system. However, if it had not been for instances such as those documented at Cleveland State Hospital, patients seeking psychiatric treatment today may still be subjected to such horrors. Lucy Sweatt was a step ahead of her race at the time, she learned to read and write during a time when blacks were not encouraged to do so. She went on to become a teacher and witness historic changes in the public school system with the inception of interscholastic competition among black schools. I always knew I was special and I have always felt a strong connection to this great place called America. After learning that my bloodline had a hand in shaping the economic and business cultures in America, I now know where those feelings came from.

None.

Author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

©2018 Latrese. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.