MOJ

eISSN: 2573-2919

Short Communication Volume 8 Issue 3

Universidad de Málaga, Spain

Correspondence: Jesús C Montosa Muñoz, Universidad de Málaga, Spain, Tel (+34) 680 284 911

Received: June 16, 2023 | Published: June 28, 2023

Citation: Montosa-Muñoz JC. Application of the method of social areas and multivariate analysis in peri-urban areas of Andalusia (Spain). MOJ Eco Environ Sci. 2023;8(3):117-127. DOI: 10.15406/mojes.2023.08.00281

We apply social area analysis, traditionally used for intra-urban areas of cities, to a space in transformation: the urban fringes in Andalusia (Spain). We also show that multivariate analysis (both exploratory factorial analysis and cluster analysis) is highly adaptable for use in urban fringes in the region. The suitability of exploratory factor analysis is confirmed, as it allows an optimal factorial structure for the spatial microanalysis of 'census tracts' as the smallest units with official statistical information in Spain. This is done in order to reduce a large number of variables to four factors: youth and recent urban expansion, traditional rural society, suburban society and residential recreational function.

Keywords: social areas analysis, exploratory factor analysis, suburbs, suburbanization, historical urbanism, Andalusia, Spain

Theory of social areas

The analysis of social areas designates the intraurban differentiation of social areas according to a theoretical model that, although questionable, has proven to be valid at the operational level in several cities of the developed world. D. Timms compiled a list of studies using the Shevky & Bell model of social area analysis who coined the term urban mosaic as a result of intraurban differentiation. 1,2

Besides the work of Timms, which compiles the applications of the analysis of the social area of Shevky & Bell (Shevky & William, 1949; Bell, 1955), there are other works that have applied the analysis of the social area to the Spanish cities. The results of these studies have been transferred to urban cartography, for example, in the application of social area analysis to the city of Malaga1 and to the ten largest cities in Andalusia.2 The analysis of the social area has also been applied in other Spanish cities. Other examples, to name a few, are the unpublished doctoral thesis on the city of Alcorcón3 or in the study on the city of Valencia4 with results that demonstrated the suitability of the model at an intraurban scale. Although it is worth mentioning that it has been applied to the urban periphery, in the cities of Villena (Alicante), Yecla (Murcia) and Almansa (Albacete). The application of multivariate analysis, specifically exploratory factor analysis and cluster analysis, has not been used too many times in urban fringes although they share with cities during its industrial stage its social heterogeneity that constitutes a necessary condition to apply these model from urban to periurban context.

From the multivariate analysis it is expected that large-scale variables or supervariables can be extracted that show this process: factor of recent urban expansion and youth of a migrant population of urban origin, so the name of the factor is associated with such urban diffusion processes (factor 1); together with a traditional rural society representing the local population that remains in the peri-urban mosaic, as well as areas not reached by urban diffusion (factor 2). In other places, suburban people and urban origin population involved in the processes of suburbanization (factor 3) and, finally, the secondary residence or residential tourist function linked to the conversion of second residences into permanent residences in peri-urban areas and in which residential tourism is present as temporary as permanent residences for retired foreign population of high purchasing power, and which is a non-economic migration (factor 4). Analyzing the degree of intensity of suburbanization, we have selected factor 3 and using K-Media, we have different degrees of suburbanization intensity in the peri-urban areas of the selected urban agglomerations in Andalusia. According to the concept of suburbanization, Zoido et al.5 defined it as follows:

A form of land occupation in which a major city, affected by rapid growth, generates the appearance in its surroundings of a metropolitan crown or crowns of functionally dependent population nuclei, but without any legal or administrative scope. This unit is sometimes considered a de facto metropolitan area, but without legal scope (translated into English by author).

A proposal from social areas theory to peri-urban areas in Andalusia

Urban society is far from being a society with similar grade of social homogeneity in comparison to traditional rural society was. The abundant works carried out about the city throughout the twentieth century gave rise to an analysis of the social area6,7:

The studies of Shevky & Williams on social differentiation in Los Angeles (LA) (1949) and Shevky & Bell in San Francisco (1955) resulted in a macrosocial theory that associated residential differentiation with what are considered the three major axes of the social structure: the economic situation, the family situation and the ethnic situation.

The city has traditionally been a place where inequality in social areas is reproduced following the Shevky & Bell model of social status or social rank, family/life-cycle status and ethnic status, to which McElrath (1968) added migration status as another axis of social differentiation.

Regarding periurban areas, the 'Post-fordist cities' expanded into their fringes through a suburbanization process originated by exurban inhabitants whose new neighbourhoods were built with the purpose to become housing developments where anyone can live with enough quality of life. For that purpose, these suburbs were built with semi-detached houses and detached houses in housing developments. Suburbanization was originated by an 'urban sprawl' process from a main city to its 'area of attraction' that ended being turned into 'suburbs' or 'satellites cities' and at the same time, they could become a perfect location for certain undesired urban uses considered as inappropriate and unhealthy for urban inhabitants so they were located in urban peripheries (Figure 1).

1This research work is based on previous research papers by Montosa Muñoz, J.C. (2014). Aplicación del análisis multivariante a espacios en transformación: las periferias de las mayores aglomeraciones urbanas andaluzas. Boletín de la Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles (BAGE), (65). https://doi.org/10.21138/bage.1745; and by Montosa-Muñoz, J.C. & Reyes-Corredera, S. (2021). Propuesta metodológica de análisis de áreas sociales y multivariante en franjas periurbanas de Andalucía (España) a comienzos del milenio. Estudios Geográficos, 82(291), e077. https://doi.org/ 10.3989/estgeogr.202188.088

2This research work took the delimitation proposed by the Junta de Andalucía in 1994 (Autonomous Government of Andalusia), before approving the Law of Spatial Planning of Andalusia [LOTA] of 1/1994 currently repealed. This initial delimitation was published in several issues of the Official Gazette of the Junta de Andalucía (BOJA) no. 97 and 98 of 28 and 30 June 1994, with a view to serving as an initial frame of reference for the recognition and delimitation of Andalusian agglomerations which were subsequently revised by Decreto 206/2006, of 28 November, Plan de Ordenación del Territorio de Andalucía (POTA) published in BOJA, no. 250 (2006) which recognizes the flexible nature in the delimitation of 10 Regional Centres in Andalusia. From this initial delimitation considered valid for my research purposes, because it meets geographical criteria and delimits homogeneous spaces, such as: the Aljarafe platform and the Alcores platform and the Vega in the urban agglomeration of Seville; the eastern and western coast of Malaga, the Montes de Málaga and the Vega del Guadalhorce in the agglomeration of Malaga; the Vega Media of Granada and Vega de Granada, both in its northern sector and in the southern sector which are asymmetrical from a functional point of view and; finally, the Bay of Cadiz where municipalities linked to the economic activity of the Bay of Cadiz are integrated. There are other proposals based on different criteria, among which those based on daily mobility for work reasons as an indicator of the degree of dependence versus functional autonomy of the crown of immediate influence to a main or central city of said urban agglomeration that exerts a centrality or considerable attractiveness despite the processes of urban decentralization that began in the 1980s and continued until the bursting of the housing bubble that gave way to the Great Recession (2008). It is not news that one more contribution does not contribute to the consensus, but in fact, there was no definitive delimitation that serves as a universal reference until the Eurostat proposal (2021) published in Spanish (2022) which uses mesh of cells of 1km and of 250m to allow evolution studies without depending on delimitations by administrative divisions that are as random as ephemeral and unstable and, therefore they don't favor comparative studies at supranational level or at more detailed scales from a local, regional, national or international scale.

The first exploratory model (Figure 2) takes a characteristic of fertility: children under five years of age, and a characteristic of urbanization: houses built after 1991, as identifiers of the relatively recent origin of suburbanization in Andalusia. For the second model (Figure 3), two variables were selected: young families with minors in their care, and single-family dwellings built between 1991 and 2001 as they have more relevant elements in the thesis that I intend to validate: the existence of a change of residence by a change at a stage in the life cycle based on the formation of a home.

Some figures were represented using a scatter diagram with two axes that show better goodness of fit in the second model than in the first (Figure 2) (Figure 3). In the first model, both in terms of 'point cloud' concentration of the cases included in the first sociogram and in terms of higher coefficient of determination is less representative than the second model. In the second model, whose scatter graph shows greater scattering of the 'point cloud' and a structure of social and family axes less correlated, the coefficient of determination is closer to zero value. It is a proposal that uses variables with little dependence on each other, a condition that must be taken into account for the analysis of factor ecology to provide satisfactory results.8

The concept of increasing scale is essential in the Shevky-Bell theory. The idea was inspired by C. Clark and the scale of a society can be defined as the number of people who are interrelated and the intensity of these relations. Increase of scale produces an increase in the heterogeneity of the population such that any large-scale society presents profound economic, regional and demographic alterations, with the consequent alterations in social relationships3.

In the Shevky model, the classification uses the migratory status that replaces the ethnic status, giving a profile that is the result of the combination of two categories: social rank or socioeconomic status and family rank or status. This use of the sociogram is appropriate when combined with the migratory status in the Andalusian case that was more representative of the Andalusian population than the ethnic status. Thus, a high social rank coincides with a low immigration status. However, this is not the case in our case, but quite the opposite: a high social rank is associated with a high migratory status due to the importance achieved by the group of tourists resident in tourist areas, whose meaning is very different from the impact of the arrival of migrant population of rural origin in urban social areas between the 1960s and 1970s.

The typology of areas comes from a combined consideration between indices I and II (economic situation and family situation) that gives rise to 16 basic types that are broken down into 32 if we consider the migratory status. Each of these indices is set by the simple average of the score in each variable. To standardize the scale, a point system was applied with values between 0 and 100.

Thus, the resulting sociogram of the social areas is as follows: the columns order the intervals of the social rank indices (0-24, 25-49, 50-74 and 75-100), which are numbered from 1 to 4 by increasing score. Rows show family status intervals from top to bottom, in descending order (75 to 100, 50 to 74, 25 to 49, 0 to 24).

In the model to adapt to the peri-urban areas of Andalusia, the starting point was the premise that society has changed since the model was developed: from an industrial society to a post-industrial society, where services and a tertiary industry have the most relevant weight in the economic structure.

In this society, rural-urban mobility has become urban mobility from city to 'some place' that can't be defined as a country could be considered by our ancestors but a country with both urban and rural characteristics due to an urbanization induced from a main city or a metropolis to their urban peripheries what is known as residential suburbanization because it's basically due to a change of residence.

In a process of residential mobility, working class had a limited participation, in comparison to social middle and social middle-upper classes workers due to residential mobility implies a separation between place of residence and labour place, at least, this happened in their beginnings with an economic cost for an necessary daily mobility due to labour reasons for daily commuters but with a relevant economic cost that is not possible to be paid by workers with low or even middle incomes whose incomes come from a unique salary and probably from an eventual job.

This residential mobility was due to the consideration of housing as desire rather than necessity. In this case, there was free choice: the desire to live in a certain type of housing, in low density urbanisations and single-family homes suitable for family homes with minor people in their care. It doesn't answer to a migration due to a rural exodus, as it happened in Spain from the 1960s to the late 1970s, as a stage into family status that coincided with young couples newly formed after their emancipation from their parents' homes.

The limited nature of emancipation especially among young people as they do not have the necessary income, not only to leave their parents' home not even to form a family because they are currently unable to form families what it means that the process of suburbanization has been ceased when a family is formed with minors and dependent family members that it's not possible without a previous consolidation in a job: in a permanent job, a basic condition before formation of a family among young adult people.

It is therefore a residential mobility whose protagonists were middle and upper-middle social class workers whose incomes comes from a salary rather than an estate origin (Montosa Muñoz' translation from Susino Arbucias' texts, 2007). The reasons for seeking a residence on the outskirts are not clear at all: sometimes it is the result of a necessity (young family status), sometimes it was the result of a desire (medium and mature family status) but the price of housing is not relevant in a strict way, although in the suburbanization that took place from the 1980s to 2008, housing prices were not an intrinsic goal: people were not looking for a cheap housing but a relationship between quality and price in housing or in an urban development that was cheaper in comparison to similar price and quality offered in main cities of an urban agglomeration or in urban region, in case of Madrid and Barcelona. As a general rule, they opted for a detached house or blocks in exclusive areas for their owners (common green areas, common recreative equipment, private swimming pools and private parking for owners) (Table 1) (Table 2).

|

Social status |

Very low |

Low |

High |

Very high |

|

Bay of Cadiz-northern sector |

- |

0.93 |

1.13 |

1.62 |

|

Bay of Cadiz-central sector |

0.75 |

0.94 |

1.21 |

0.45 |

|

Bay of Cadiz-southern sector |

2.36 |

1.15 |

0.72 |

0.35 |

|

Vega de Granada-northern sector |

- |

1.41 |

0.82 |

0.29 |

|

Vega de Granada-southern sector |

- |

0.7 |

1.61 |

0.54 |

|

Vega Media of Granada |

2.7 |

1.58 |

0.23 |

- |

|

Guadalhorce Valley |

2.48 |

1.44 |

0.42 |

- |

|

Malaga-West Coast |

0.2 |

0.86 |

1.48 |

- |

|

Montes de Málaga |

9.42 |

0.82 |

- |

- |

|

Málaga-East Coast |

- |

0.68 |

1.54 |

1.05 |

|

Central Escarpment of the Aljarafe Platform |

0.16 |

0.7 |

1.16 |

2.77 |

|

Southern Escarpment of the Aljarafe Platform |

3.55 |

1.15 |

0.53 |

0.35 |

|

Northern Escarpment of the Aljarafe Platform |

1.5 |

0.98 |

0.51 |

3.28 |

|

Los Alcores Platform |

1.07 |

0.95 |

0.95 |

1.54 |

|

Vega de Sevilla |

2.58 |

1.73 |

0.07 |

- |

Table 1 Index of localisation.9 Social status in peri-urban areas in Andalusia

Sources: National Statistics Institute: Population and Housing Censuses 2001. Ocaña-Ocaña, C. (1998).

|

Family status |

Young |

Mature |

Advanced |

Aged |

|

Bay of Cadiz-northern sector |

- |

0.58 |

0.76 |

1.27 |

|

Bay of Cadiz-central sector |

1.47 |

0.17 |

0.68 |

1.37 |

|

Bay of Cadiz-southern sector |

- |

0.77 |

1.49 |

0.59 |

|

Vega de Granada-northern sector |

- |

- |

1.91 |

0.28 |

|

Vega de Granada-southern sector |

- |

1.39 |

1.58 |

0.44 |

|

Vega Media of Granada |

- |

0.93 |

0.92 |

1.09 |

|

Guadalhorce Valley |

- |

1.64 |

1.14 |

0.82 |

|

Malaga-West Coast |

- |

- |

0.21 |

1.84 |

|

Montes de Málaga |

- |

- |

1.24 |

0.9 |

|

Málaga-East Coast |

- |

- |

1.22 |

0.92 |

|

Central Escarpment of the Aljarafe Platform |

1.95 |

1.93 |

0.72 |

1.14 |

|

Southern Escarpment of the Aljarafe Platform |

- |

1.29 |

1 |

0.99 |

|

Northern Escarpment of the Aljarafe Platform |

- |

3.08 |

1.11 |

0.7 |

|

Los Alcores Platform |

2.44 |

1.04 |

0.98 |

1 |

|

Vega de Sevilla |

4.55 |

2.07 |

0.99 |

0.85 |

Table 2 Index of localisation. Life-cycle/Family status in peri-urban areas in Andalusia

Sources: National Statistics Institute: Population and Housing Censuses 2001 and Ocaña-Ocaña, C. (1998).

In Los Alcores platform, despite a peri-urban industry in the municipality of Alcala de Guadaíra10,11 whose residential mobility is mainly composed by a population with social middle class and industrial workers. Regarding life-cycle status, a dwelling afterwards leaving their parents' home is majority in central part of Bay of Cadiz urban agglomeration, so as in Seville periurban area. The reason of a periurban residential election is more due to desire rather than necessity in Cadiz periurban area concretively in the municipality of Chiclana de la Frontera so as in la 'Vega de Granada' where this answer was less frequent on north of la 'Vega de Granada' than on south of it, besides it reaches a high value in Guadalhorce Valley and on east coast of Malaga periurban area. An advanced status is also relevant on north and central part of Bay of Cadiz periurban area, on west coast of Malaga and in central part of the scarp next to the platform of Aljarafe and in the platform of Los Alcores, all of them situated in Seville urban agglomeration, but it is more due to a desire choice rather than necessity, as it corresponds to a certain social status whereas low social status is reflected in the aged periurban areas so as in rural areas in the central part of la 'Vega de Granada'.

In referring to migratory status, in which we include the population who weren't born in the municipality in which the respondent lived—i.e., migrant population that shown high levels of urban segregation due to social or origin reason to such an extent that both are frequently linked. This would confirm the hypothesis that foreign people are segregated in exclusive areas but far away from local people in competence for living in higher environmental quality areas that usually coincide with the higher prestige social areas12. This happens in suburbanized areas with urban sprawl13 due to residential tourism in la 'Costa del Sol' de Malaga and other coastal areas specialized in tourism where there is a strong link with social segregation due to the foreign origin of a population with high purchasing power and ageing people.

In conclusion, the possibility of applying a method that is has traditionally been employed for intraurban analysis to urban fringes gives interesting results as an indicator that shows the social and sociological changes in the exurban population in Andalusian periurban areas, at least in the four urban agglomerations that were selected for this study. This is due to that social changes induced by residential movements from central cities as well as internal forces due to residential tourism and periurban industry. Both of them share social status but not family status at the same time since one arises from an initial stage of a family of life-cycle status when the age for families formation in 1990 were of 28 years old for men, and of 26 years old for women, a situation that it has changed from the beginning of the twenty-first century to nowadays, when the age of forming families in Spain became 31 years old for men, and 29 years old for women14.

3Estébanez-Álvarez, J. (1988). Chapter 4: Los espacios urbanos, pp. 357-585.

4According to an initial proposal of the Andalusian Regional Government before the elaboration of the different Regional Plans for Urban Agglomerations in Andalusia. Decreto 206/2006, 28th November 2006. https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/organismos/fomentarticulaciondelterritorio yvivienda/areas/ordenacion/pota/paginas/plan-pota.html. This delimitation proposal wasn't the definitive either, because it was modified afterwards including the delimitation for Regional Plan of Andalusia itself, because 'Subregional Plans themselves were modified more ahead. Therefore, the changes after these delimitation shown in Figure 1, took place after the '1994 Proposal' that it served for an initial delimitation based on municipalities as administrative reference units that integrated the different 10 Regional Centers in Andalusia equivalent to 10 urban agglomerations recognized so by Regional Government. The delimitation used in my doctoral thesis and in this research, uses the '1994 Proposal of Junta de Andalucía' due to its geographical content, and for showing quite well the boundaries of the first metropolitan crown or so called 'suburban ring'.5The Official Gazette of the Government of Andalusia (BOJA), no 97 of 28/06/1994. Agreement of 10 May 1994, of the Governing Council, formulating the urban agglomeration of Cadiz Bay. (1994a), no 97 of 28/06/1994, Acuerdo de 10 de mayo de 1994, del Consejo de Gobierno, por el que se formula el Plan de Ordenación del Territorio de la aglomeración urbana de la Bahía de Cádiz. (1994a). https://www.junta deandalucia.es/boja/1994/97/6

6Official Gazette of the Government of Andalusia (BOJA), no 98 of 30/06/1994. Agreement of 10 May 1994 of the Governing Council formulating the Plan de Ordenación del Territorio de la aglomeración urbana de Málaga (1994b). https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/boja/1994/98/5

7Official Gazette of the Government of Andalusia (BOJA), no 98 de 30/06/1994. Agreement of 24 May 1994 of the Governing Council formulating the Plan de Ordenación del Territorio de la aglomeración urbana de Granada. (1994c). https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/boja/1994/98/8

8Official Gazette of the Government of Andalusia (BOJA), no 98 de 30/06/1994. Agreement of 31 May 1994 of the Governing Council formulating the Plan de Ordenación del Territorio de la aglomeración urbana de Sevilla. (1994d). https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/boja/1994/98/9

9For more information on this index, view Carrera C. et al. (1998): Trabajos prácticos de Geografía Humana, pp. 240–242.

10During the 1960s, a series of Andalusian cities leaded the region's efforts in economic modernization with the location of industries in so-called development poles which encouraged centralisation in a capital province (Feria-Toribio, 2007: 3).

11Author's information: a province is a Spanish administrative division unit created by a Spanish minister (Javier de Burgos, 1833) during the Regency of Queen Maria Cristina. The capital is the administrative center of a province.

12The concept of competition arises from the Chicago School and consists of the transposition of the ecological determinism of natural areas to social areas which have an economic market value, depending on economies of scale and lose value due to diseconomies of scale.

13This concept contrasts with rural sprawl but may not be considered an equivalent of residential suburbanisation. Both concepts refer to a model of disperse, or sprawling, development that contrasts with compact urbanization. Both of them have a low population density. Both imply environmental and economic impact on a large scale, the environmental and ecological damage of which maybe not have been economic quantified, and another is referred to people in a life-cycle formed by retirees with a high purchasing power that live during several months or the whole year in a coast resort that characterizes residential tourism, whilst young adults and middle-aged couples usually with children or teenagers, family homes more frequent that dwellings with bachelors or by couples without children. Both of them don't form family homes

14Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE) (2000). Movimiento Natural de la Población. Volume I.

Objective of this researching

The objective is to use factor analysis to verify the degree of transformation of the Andalusian peri-urban areas in order to obtain factors that allow distinguishing the characteristics of their respective peri-urban areas.

Sample

A total of 654 'Census tracts' from four of the main urban agglomerations of Andalusia were selected. The selected 4 urban agglomeration were: Bay of Cadiz, Vega de Granada, Malaga and Seville. These urban areas were defined according to criteria of geographical homogeneity. After defining the geographical boundaries of these areas, we used smaller units for which official statistical information was available, which are the 'Census tracts' that they were grouped into units with homogeneous geographical characteristics to detect possible differences or similarities between them and thus characterize each of the geographical entities, according to the results of an exploratory factor analysis.

Initial hypothesis

In our theoretical proposal, variables relative to homes formation were chosen. For this reason, demographic variables related to population of urban origin were selected as population under 15 years of age and head of households held by a single or family household, consisting of couples or single-parent families of a father or mother aged between 30 and 45 years old. We compared young adult with older people aged 65 and over mostly integrated by local and rural population who didn't participate in the process of suburbanization of a municipality weakly urban or predominantly rural, at least at the beginning of a process of suburbanization by urban diffusion originated in a main city of the different four urban agglomerations that were selected.

Our starting hypothesis, based on previous studies (survey of the doctoral thesis of the author whose field work was carried out in 1997); it is based on the consideration that the population participating in processes of suburban urbanization or suburbanization by urban diffusion possesses a certain degree of socio-professional qualification, given the high correlation between level of education and level of income, ―at least at that time―; with professions requiring secondary, if not tertiary education. Therefore, we select secondary and university education as a variable, along with professions related to managerial, technical and administrative functions.

Once again, we consider the population that did not participate in these processes, that is the rural population and, at the same time, the local population that remains outside this suburbanizing process. The variables included retirees and pensioners, the population dedicated to agriculture and construction, generally associated with the Figure 4 & 5 of the worker-peasant in peri-urban areas and with a part-time agriculture (ATP).

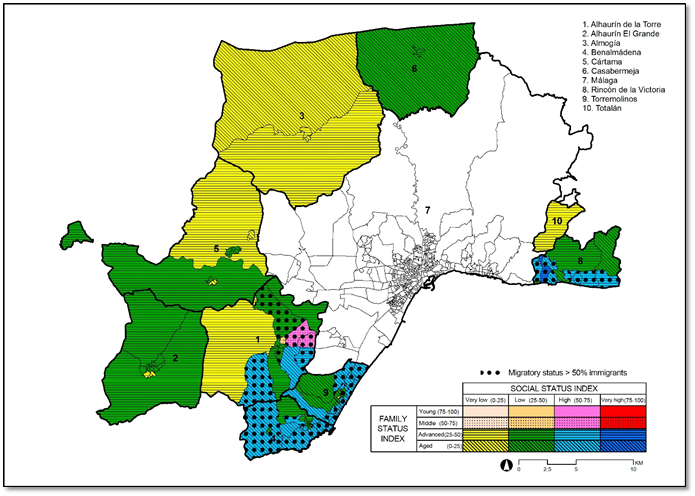

Figure 4 Peri-urban social areas in Malaga urban agglomeration.

Source: Montosa-Muñoz, J. C. & Reyes-Corredera, S. (2021). Propuesta metodológica de análisis de áreas sociales y multivariante en franjas periurbanas de Andalucía (España) a comienzos del milenio. Estudios Geográficos, 82(291), e077.

https://doi.org/10.3989/estgeogr.202188.088

Figure 5 Peri-urban social areas in Seville urban agglomeration.

Source: Montosa-Muñoz, J. C. & Reyes-Corredera, S. (2021). Propuesta metodológica de análisis de áreas sociales y multivariante en franjas periurbanas de Andalucía (España) a comienzos del milenio. Estudios Geográficos, 82(291), e077.

https://doi.org/10.3989/estgeogr.202188.088

We also selected mobility variables, since, in our initial hypothesis, we consider that the population of urban origin has a high degree of mobility for work or daily travel, compared to the local population, among those who predominated sedentary jobs or that do not require displacement of the place of residence, especially in the early phases of suburbanization in the autonomous community of Andalusia at the end of the twentieth century.

On the other hand, considering the importance of spatial mobility in areas subject to suburbanization, the variable of recent migrants was selected. This is the date of migrants counted by official statistics between 1991 and 2000 and who emigrated from a main or central city as origin of this migration which, in our research work, coincides with the capital of the different provinces: Cádiz, Granada, Málaga and Sevilla. Among the migrants, we also select migrants from the rest of the country without considering if they are of provincial, national or they have a foreign origin.

Finally, housing variables were included: recent dwellings and second homes, traditionally related to areas that suffered suburbanization by urban diffusion in a previous stage of occupation through second homes or temporary residences that under certain conditions, they became permanent or main residences.

Exploratory factorial analysis

The analysis of the main components was used, the main factors were calculated and four of them were rotated in a simple structure using the Varimax rotation17.

Conclusion

From the matrix of rotated components, the labels of each factor can be inferred based on its correlation with the variables used.

Exploratory factor analysis confirms the heterogeneity of the peri-urban areas of Andalusia at the beginning of the century (2001). We have established a series of different categories for these areas that confirm that they are territories that far from being socially homogeneous are characterized by their heterogeneity and it's appropriate to differentiate degrees of suburbanization at the beginning of the twenty-first century, which would not reach its peak until years later some years before it was abruptly interrupted by the Great Recession that began in 2008 (Table 3) (Table 4).

|

Postulates related to industrial society |

Statistical trends in industrial society |

Statistical trends in post-industrial society |

Changes in the structure of a given social system |

Analytical construct or category |

Measures and indicators of the categories |

|

Order and intensity of the relations |

Change of tasks distribution: manual production operations decrease. Supervision and control activities increase |

Change of task distribution: manual production operations decrease. Those highly qualified tasks connected to highly-specialized services increase |

Change in the range of occupations based on highly-specialized services. Urban impact: increased presence of ex-urban social middle and social upper-middle class in peri-urban areas |

Social status |

Population with secondary and tertiary level education. Population employed in qualified services |

|

Differentiation of functions |

Change of the productive structure: decrease in primary activities. Centralized activities in cities with growth of population. Decrease of family consideration as economic unit |

Transformation of the productive structure: decrease of centralized activities in cities. Decentralized to peri-urban areas. Family households multiply |

Life cycle based on household generation: Newcomers create new families in socially prestigious suburban areas |

Family status |

Young families with responsibility for minors. Single-family dwellings |

|

Complexity of organization |

Growing mobility of the population: Changing and complex population structure |

Increasing social and spatial mobility of the population also in peri-urban contexts. Segregation of the local population and suburbanites or newcomers |

Spatial redistribution. Anonymity. Isolation and social segregation in the peri-urban context between old neighbourhoods where the local population live and the residential housing developments where the suburban population lives |

Segregation goes on |

Local population segregated from the immigrant population |

Table 3 Stages for a proposal of Shevky's analytical model applied to 'suburban mosaic'

Source: Shevky & Bell, Social Area Analysis cited by Timms (1976), p. 225.

|

Variables |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

Initial communalities |

|

Illiterate People |

-0.33 |

0.66 |

-0.29 |

-0.68 |

|

|

Middle and High Educational levels |

0.26 |

-0.78 |

0.33 |

0.34 |

-0.91 |

|

Immigrants from 1991 to 2000 |

0.41 |

0.64 |

0.56 |

-0.95 |

|

|

Suburban immigrants |

0.47 |

0.73 |

0.3 |

-0.9 |

|

|

Foreign immigrants |

0.88 |

-0.8 |

|||

|

Other immigrants |

0.26 |

0.43 |

0.79 |

-0.91 |

|

|

Children (≤ 5 years) |

0.84 |

-0.75 |

|||

|

Teenagers (≤ 15 years) |

0.91 |

-0.84 |

|||

|

Head of Household aged 30 to 44 years |

0.91 |

-0.91 |

|||

|

Head of Household aged (≥ 65 years) |

-0.8 |

-0.76 |

|||

|

Farming workers |

0.53 |

-0.31 |

|||

|

Unskilled workers |

0.82 |

-0.71 |

|||

|

Construction workers |

0.6 |

-0.34 |

-0.44 |

-0.68 |

|

|

Manager and technical jobs |

-0.73 |

0.27 |

0.34 |

-0.72 |

|

|

Administrative workers |

-0.76 |

0.27 |

-0.71 |

||

|

Suburbanites commuters for labour reasons |

0.29 |

-0.26 |

0.81 |

-0.83 |

|

|

Sedentary workers |

-0.89 |

-0.83 |

|||

|

Unemployed people |

0.41 |

-0.49 |

-0.43 |

||

|

Retired and pensioners |

-0.77 |

0.32 |

-0.74 |

||

|

Dwellings (from 1991 to 2000) |

0.67 |

0.33 |

-0.58 |

||

|

Second homes |

0.71 |

-0.54 |

|||

|

Eigenvalues |

8.82 |

3.14 |

2.24 |

1.42 |

|

|

(*) Factor loadings lower than 0.25 have been omitted. |

|||||

Table 4 Factor loading matrix after the Varimax rotation

Source: Own elaboration.

The exploratory factor analysis allows confirmation of the heterogeneity of peri-urban zones in Andalusia. A series of categories have been established for peri-urban areas that confirm that they are areas that, far from being homogeneous, are characterized by their diversity, some of them came to suffer from residential suburbanization at the beginning of the present century and at different degrees of intensity, as evidenced in an article to which the reader is referred.

15Montosa Muñoz, J.C. (2014). Aplicación del análisis multivariante a espacios en transformación: las periferias de las mayores aglomeraciones urbanas andaluzas. Boletín de la Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles, (65). https://doi.org/10.21138/bage.1745

16Montosa-Muñoz, J.C. & Reyes-Corredera, S. (2021). Propuesta metodológica de análisis de áreas sociales y multivariante en franjas periurbanas de Andalucía (España) a comienzos del milenio. Estudios Geográficos, 82(291), e077. https://doi.org/ 10.3989/estgeogr.202188.088

17Addenda al curso de Postgrado de la Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia. Estadística Multivariante: una Perspectiva de Usuario. Iniciación al Uso de Software Estadístico: SPSS. 3.8. Análisis factorial exploratorio, pp. 163-184.

18En las denominaciones asignadas a los factores se siguieron las recomendaciones expresadas en su momento por quien fue mi directora de tesis: la Dra. C. Ocaña Ocaña, a quien muestro mi gratitud por su valiosa ayuda.

In conclusion, social area analysis should be seen for what it is an operative model with a great economy of means that offers an approximation to peri-urban social heterogeneity, although the sociocultural context and the moment in time at which it is applied must be taken into account due to its dynamism. Regarding cluster and factor analyses, these methods are highly suitable for peri-urban areas under the effects of different grades of suburbanization due to urban diffusion, as they allow us to obtain an optimal factorial structure and, by analysing the clusters, they are also suitable to detect where processes of suburbanization are occurring, which in turn allows us to know, with a high degree of detail through census sections, the intensity variations of suburbanization that such geographical areas represent.

The urbanization of the periphery has generated an enormous transformation of the Andalusian territory and its importance can be quantified from a demographic and physical perspective. As detailed by Cruz-Villalón,9 it has gone from 141 010.35 hectares and 1.6% of land use in Andalusia, between 1991 and 2007, to 263,264.17 hectares and 3% of the total land, that is, it has doubled in area in just over 15 years, according to data from public sources from the Ministry of Environment. However, its consequences are more severe because it represents an irreversible process, of denaturing the rustic soil, which implies a complete transformation of the concept of city and an unsustainable urbanization of the rural environment. It also changes the city, becoming more of a "machine" to inhabit rather than a "place" to live in Rubio Díaz,10 which produces an "ecocide" with irreversible and unpredictable consequences for the natural ecosystem of which human beings forget that they are also a part.

It should also to be taken into account that we are referring to a past situation at the beginning of the twenty-first century, in which urbanization of the peri-urban areas was at one of its peak and went on expanding until the Great Recession of 2008. The crisis with its well-known consequences and the bursting of the housing bubble interrupted this process of suburban growth.11–63

None.

None.

The authors declares that there is no conflict of interest.

©2023 Montosa-Muñoz. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.