Journal of

eISSN: 2574-8114

Review Article Volume 11 Issue 3

1Departement of Textile and Leather Engineering, National Advanced School of Engineering of Maroua, University of Maroua, Cameroon

2National Advanced School of Engineering of Maroua, University of Maroua, Cameroon

3Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit GIZ), Cameroon

4Department of Fine Arts, Faculty of Arts and Humanities, University of Maroua, Cameroon

Correspondence: Hermann Tchonang Ndogmo, Departement of Textile and Leather Engineering, National Advanced School of Engineering of Maroua, University of Maroua, P.O. Box 58 Maroua, Cameroon

Received: April 19, 2025 | Published: May 16, 2025

Citation: Ndogmo HT, djonga PND, Thea CN, et al. Modernization of Lépi: repositioning a heritage fabric in Cameroonian fashion. J Textile Eng Fashion Technol. 2025;11(3):105-110. DOI: 10.15406/jteft.2025.11.00411

Lépi, the traditional fabric of the Sudano-Sahelian peoples—particularly in Cameroon and Guinea—is undergoing a major transformation through its gradual integration into contemporary fashion. This article explores the technical, symbolic, and aesthetic characteristics of this artisanal textile, while offering a contextualized analysis of its current uses by African designers. Through a comparative and creative approach, it highlights the stylistic potential of Lépi in ready-to-wear fashion, haute couture, and accessories, drawing on recent research and field initiatives. The study also emphasizes the economic and cultural stakes involved in its revalorization: structuring local value chains, cultural diplomacy, and the development of creative industries. This work thus proposes a new textile grammar, where tradition and innovation meet to position Lépi within the future of African fashion design.

Keywords: Lépi, fashion design, heritage textile, contemporary African fashion

Since the 2020s, African fashion has experienced a renewed interest on the global stage. This momentum is driven by the intersection of contemporary innovation and reinterpreted traditions. Several reports highlight that this sector could become a major economic engine within the next decade.1,2 According to UNESCO, Africa possesses all the assets needed to position itself among the global fashion leaders, thanks to a young generation of talented designers and the growing appreciation for artisanal know-how.1

Today, the continent hosts over thirty Fashion Weeks annually, and global demand for African haute couture continues to rise, with an estimated 42% increase projected over the next ten years.2 This dynamic is accompanied by a particular enthusiasm for heritage textiles, which are increasingly featured in contemporary creations. Exhibitions such as Africa Fashion, presented at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London in 2022, have highlighted the richness and modern relevance of traditional African fabrics.3

Many designers are part of this trend by reintegrating historical textiles into their collections. In Nigeria, ancestral techniques such as adire and aso oké are being revived by influential brands like Maki Oh, Tiffany Amber, and Kenneth Ize.4 These initiatives reinforce cultural pride while supporting local artisans. Cameroonian designer Imane Ayissi, recently welcomed into Paris Haute Couture, combines Cameroonian raffia with Ghanaian kente to create a hybrid stylistic language focused on sustainability.5

Amidst the current transformations shaping the African fashion landscape, Lépi emerges as a heritage textile of significant cultural and creative potential. Originally from the Fouta Djallon region of Guinea and also prevalent in northern Cameroon, Lépi is a handwoven, indigo-dyed cotton fabric traditionally associated with ceremonial contexts—such as weddings, initiation rites, and religious festivities.6 Valued for its understated aesthetic, symbolic richness, and lightweight texture, Lépi is customarily used in the making of gandouras or boubous worn by high-ranking figures including traditional rulers, religious authorities, and other respected community members. In these settings, Lépi conveys notions of wisdom, purity, and spiritual refinement. As such, it is regarded as a prestigious and costly garment, deeply esteemed within traditional sociocultural frameworks.

Yet, despite its cultural richness, Lépi remains largely underutilized outside its ceremonial context. This raises a central question: how can Lépi transition from a locally ritualistic use to a contemporary creative material, while preserving its cultural rootedness? More specifically, how can it be integrated into haute couture, urban ready-to-wear, or even professional attire without compromising its identity?

To address this issue, the present article adopts a multidisciplinary approach. It is structured in three parts: first, a technical analysis of Lépi—including its weaving techniques, dyeing processes, and material properties; second, an exploration of concrete stylistic pathways for adapting the fabric to contemporary uses; and finally, a discussion on the economic, cultural, and identity-related implications of reintegrating Lépi into the current African fashion landscape.

This study adopts a qualitative, exploratory approach based on the complementarity between scientific documentation, technical textile analysis, and field surveys. The research is structured around three methodological pillars.

First, a literature review was conducted to characterize the Lépi in both its material dimensions (structure, weight, indigo dyeing method) and symbolic aspects (ritual uses, social status, cultural value). This review drew upon scientific articles, technical reports, institutional documents, and specialized publications focused on African textiles, particularly those from the Sahel region.

Next, semi-structured interviews were conducted between February and March 2024 with three Cameroonian fashion designers working in the field of Afro-contemporary clothing design. These interviews took place in Garoua, Yaoundé, and Douala. Their purpose was to gather the designers' perceptions of Lépi as a creative material, identify the technical or aesthetic barriers to its use, and explore concrete stylistic possibilities. The collected statements were thematically analyzed around three main categories: the aesthetic perception of Lépi, its constraints in contemporary fashion design, and suggestions for its integration into hybrid cuts or textile combinations.

Finally, direct observations were carried out during cultural and professional events, notably at the SIAC (International Handicraft Fair of Cameroon) and the Guinea Fashion Fest. Visits to tailoring workshops and artisanal fairs enriched the analysis by providing a deeper understanding of field dynamics. These empirical elements help shed light on the feasibility conditions and prospects for repositioning Lépi as an active material within the framework of a sustainable African fashion movement.

Lépi: Between cultural memory and contemporary marginalization

Lépi is much more than just a textile: it serves as a living archive of the collective memory of the Sudano-Sahelian peoples, particularly in the northern regions of Cameroon. Among the Fulani, Toupouri, Musgum, and Kotoko communities, it carries deep identity symbols, reflects social hierarchy, and embodies spirituality.7 Used during major events—weddings, funerals, enthronements—it evokes notions of purity, nobility, and connection with the ancestors. Wearing Lépi is never trivial: it is often reserved for authority figures and sacred occasions, reinforcing its status as a prestigious fabric.

Historically, its production was part of a well-structured chain of craftsmanship, involving weavers, dyers, and traditional seamstresses. Locally grown cotton was first hand-spun and then woven into narrow strips using horizontal wooden looms. The fabric was initially natural white—unbleached and raw—before being transformed through dyeing. This raw cotton, untreated and unbleached, had ideal absorbent properties for plant-based indigo dyeing, which enhanced both the richness of the color and the durability of the fabric. In some communities, the ability to produce high-quality Lépi was even a marker of family distinction. It became part of a dowry, an honorary gift, or an intergenerational heirloom.8

The term “lépi” is thought to derive from a local word meaning “to tie” or “to bind,” referring to the resist-dyeing method used before coloring. The fabric is folded, tied, or sewn in specific ways to shield certain areas from the dye—using a technique similar to tie and dye. Immersed in successive baths of natural indigo, the cotton takes on deep blue shades adorned with irregular or striped graphic patterns. Each line results from a deliberate, often symbolic, gesture. Lépi is characterized by its lightness, soft texture, and deep blue hue—frequently associated with spiritual protection in Fulani culture.9 It is said that this shade wards off evil spirits and embodies wisdom

Le Lépi est notamment utilisé pour confectionner des gandouras – longues tuniques traditionnelles portées par les hommes lors de cérémonies importantes. La gandoura en Lépi, sobre et fluide, est un signe d’appartenance sociale élevée. Elle est souvent réservée aux chefs, notables, dignitaires religieux ou aux mariés. Dans ce contexte, le Lépi devient bien plus qu’un vêtement : c’est un insigne de dignité et un vecteur d’expression culturelle profonde.

Pourtant, malgré cette richesse symbolique et esthétique, le Lépi souffre aujourd’hui d’un certain déclin dans les usages urbains. Souvent considéré comme un tissu « ancestral » ou « rural », il est écarté des circuits de la mode moderne au profit de textiles perçus comme plus dynamiques ou standardisés, comme le wax ou le bazin. Cette marginalisation est accentuée par le manque de valorisation culturelle institutionnelle, l’absence d’initiatives de design contemporain centrées sur ce tissu, et la rareté de sa production en milieu urbain.10

Il devient donc urgent de reprogrammer l’imaginaire collectif autour du Lépi, non plus comme simple habit cérémoniel cantonné à la tradition, mais comme une matière de design contemporain, capable de véhiculer un récit visuel riche et d’intégrer les tendances stylistiques actuelles. Il s’agit de créer une nouvelle grammaire esthétique du Lépi – une qui respecte son origine tout en le projetant dans les pratiques vestimentaires du XXIe siècle.

The production process of Lépi – Technique and cultural significance

The making of Lépi is based on a series of artisanal steps deeply rooted in the textile traditions of Sahelian societies. This process, orally transmitted across generations, combines precise technical gestures, cultural symbolism, and natural materials sourced from the local environment.

Spindle spinning

The first step involves the manual transformation of raw cotton into yarn using a traditional spindle. This technique, mainly practiced by women, requires stretching and twisting the fibers to produce an even thread. In the northern regions of Cameroon, this task is often carried out collectively within family-based structures (Figure 1).11

Figure 1 Traditional spindles used for artisanal cotton spinning in Chad.

Source: Pinterest (https://www.pinterest.com.mx/pin/571816483912464385/

This traditional method helps preserve the quality of the fibers and produces a thread that is both flexible and durable, ready to be used on looms.

Artisanal weaving

The spun yarn is then set up on a traditional loom, typically horizontal or vertical depending on the region. In Cameroon, artisans from the North use horizontal looms to weave long, narrow strips (gabaga), which are later sewn edge to edge to create large textile pieces (Figure 2).12

Figure 2 Artisan in Tokombéré (Cameroon) at a vertical loom – Lépi fabrication.

Source: Personal photograph, Tchonang Ndogmo Hermann, 2024

Weaving is not merely a technical operation; it is part of a textile grammar in which each motif and each arrangement of strips carries symbolic value, memory, or a message. It is therefore a visual language unique to the community that produces it.

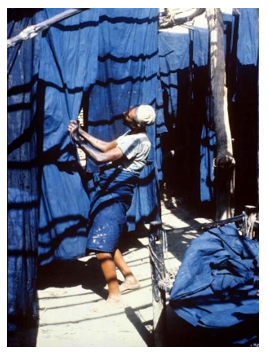

Indigo dyeing

The woven fabric is then dyed with indigo following an ancestral process involving local plants such as Indigofera tinctoria. This stage occurs in three phases13:

Figure 3 Indigo dyeing, an ancestral traditional technique.

Source: Afrika Tiss (https://www.afrikatiss.org/Articles/teinture-indigo/)

Technical analysis of Lépi fabric

Structure, dyeing, and handling: Lépi is a 100% cotton fabric, traditionally handwoven on manual looms using a plain weave structure. The finished piece typically consists of narrow strips called léfols (about 30 cm wide and 180 cm long), sewn edge to edge to form a cloth measuring approximately 1.20 × 1.80 meters.14 This manufacturing method produces a very lightweight textile that is not very elastic but remains supple—suitable for flowing cuts and strong enough for garment making. The cotton yarn used is often spun as a double-ply thread, which enhances durability while maintaining the fabric’s fineness.15

The dyeing technique of Lépi relies exclusively on natural indigo. The process begins with the fermentation of indigo plant leaves, mixed with lime or ashes, and then with plant-based sugars to activate the reduction of the dye compound.16 The fabric is then immersed in this deoxygenated dye bath and only turns blue when exposed to air, through an oxidation reaction. To create patterns, the fabric is tied or folded before dipping, using resist techniques similar to shibori or batik, although unlike wax prints, Lépi does not involve the use of wax.17

Compared to other fabrics used in African fashion, Lépi has a lower weight than wax print (140–160 g/m²), bazin (approximately 130–150 g/m² with stiff finishes), and is far lighter than denim (> 300 g/m²). Its lighter weight (< 100 g/m²) makes it more fluid and easier to handle.18 In terms of breathability, its airy structure and fineness provide excellent air permeability, making it particularly suitable for hot climates. Its natural flexibility allows it to adapt well to draping, pleating, and the soft volumes favored in contemporary fashion design.19

However, its wash stability depends on the quality of the artisanal dyeing process. While natural indigo is generally durable, it can bleed if not thoroughly rinsed or if washed with harsh detergents. As such, care instructions must follow the same precautions as for other hand-dyed fabrics.20

In terms of compatibility with modern cuts, Lépi proves to be especially versatile. Its lightness, plain texture (free from directional printed motifs), and the usable length of its woven pieces make it easily adaptable to contemporary patterns: fitted dresses, blouses, tailored jackets, or straight trousers.14 Unlike bazin (stiff and glossy) or denim (dense and less breathable), Lépi offers greater design freedom while maintaining a strong visual and cultural identity.

Finally, from an ecological standpoint, Lépi represents a sustainable and natural alternative: local cotton, plant-based dyeing, and low-impact artisanal transformation. These features make it fully compatible with the ethical demands of today’s fashion industry (slow fashion, eco-design, short supply chains).15

Between tradition and innovation: repositioning Lépi as a design textile

In a fashion world increasingly oriented toward sustainability, cultural identity, and the reappropriation of local know-how, Lépi presents considerable potential. Long confined to ceremonial use, this handwoven, indigo-dyed fabric produced by the Fulani communities of the Fouta-Djallon is now being reinterpreted by a new generation of designers and structured artisanal initiatives, transforming it into a genuine material for contemporary creation.16–18

Cultural transformation

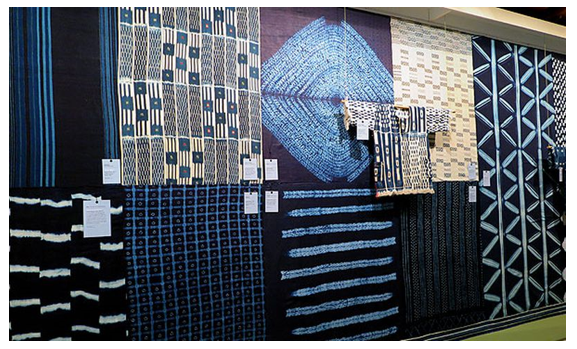

The repositioning of Lépi within the fashion industry begins with a cultural re-reading. Brands such as Tokkora, founded by Aliou Diallo, collaborate with artisans to produce 100% locally made fabric that adheres to modern quality standards while preserving its traditional roots.19 Similarly, La Rouhe Design, led by Fatou Koné, reimagines Lépi through modern cuts and combinations with noble materials to create haute couture collections evoking "Guinean heritage".20 The National Office for the Promotion of Handicrafts, along with the African Intellectual Property Organization (OAPI), has registered Lépi as a Protected Geographical Indication (PGI), officially recognizing its origin, production methods, and cultural value.19 This legal recognition contributes to enhancing its visibility and worth among both the general public and design professionals.

Aesthetic transformation

Lépi holds immense stylistic potential. The PGI (Protected Geographical Indication) specifications distinguish several variants (off-white plain, striped, indigo-dyed), allowing designers to expand their visual palette.20 Some creators blend Lépi with wax prints or denim to create material and texture contrasts within modern cuts. Moodboards from recent Guinean collections showcase Lépi used in tailored jackets, minimalist dresses, and contemporary accessories (bags, bow ties, shoes). With its understated appearance and matte finish, the fabric lends itself well to refined and sophisticated designs that appeal to an urban and international audience (Figure 4).15

Figure 4 Hand-dyed Lépi fabric, a symbol of Fulani cultural identity, recognized as a textile heritage of Guinea.

AfricanTextil. (n.d.). Lépi – Guinea. AfricanTextil. (2020).

This global repositioning does not seek to distort Lépi, but rather to open it up to new applications: from formal attire to ready-to-wear fashion, including urban styles and haute couture creations. It is now conceivable to design a technocratic suit, a tailored jacket, or a structured dress made from Lépi-provided that its technical constraints and symbolic weight are carefully respected.

Thus, through a cultural, technical, and aesthetic transformation, Lépi no longer merely dresses the past. It becomes a fabric of the future-anchored in an African fashion scene that asserts its identity without forsaking its traditions.

Stylistic pathways and contemporary cuts: toward a grammar of modern Lépi

The Lépi fabric, with its lightweight texture and subtle patterns, offers fertile ground for designers seeking to bridge textile heritage and stylistic modernity. Its aesthetic simplicity makes it an ideal material for exploring contemporary clothing forms that are understated yet deeply rooted in identity.

Lépi in contemporary silhouettes

Many African brands and fashion houses are reimagining Lépi by integrating it into garments with modern lines. For instance, the La Rouhe Design house offers ensembles featuring asymmetrical cuts, puffed sleeves, split collars, or layered elements.20 These stylistic choices highlight Lépi’s adaptability to minimalist aesthetics while maintaining a strong cultural resonance. The use of Lépi’s characteristic lateral bands in tailored suits or flowing dresses allows for a subtle graphic interplay between tradition and modernity. The fabric’s discreet patterns lend themselves well to the creation of fitted blouses, midi or long dresses, and stylized men’s tunics—design directions supported by Rice’s21 research on the narrative use of traditional textiles in contemporary fashion.22

Lépi in contemporary silhouettes

Many African fashion houses and brands are reimagining Lépi by incorporating it into garments with modern lines. For instance, La Rouhe Design offers ensembles that feature asymmetrical cuts, balloon sleeves, split collars, or layered elements.20 These design choices highlight Lépi’s ability to adapt to minimalist aesthetics while retaining its cultural depth. The use of characteristic side bands found in Lépi, integrated into tailored pantsuits or flowing dresses, creates a subtle graphic dialogue between tradition and modernity. The fabric’s discreet patterns lend themselves well to the design of fitted blouses, midi or long dresses, and stylized men's tunic’s approaches supported by Rice's (2020) research on the narrative use of traditional textiles in contemporary fashion.23

Graphic and hybrid experimentations

Some fashion houses embrace hybridization by combining Lépi with fabrics such as wax print, silk, or denim, brought together through paneling, embroidery, or layering. These combinations expand the aesthetic palette and give the garments greater visual depth. Moodboards from AST Design and Tokkora, for instance, showcase tailored jackets where the sleeves feature Lépi’s characteristic stripes, while the front panels are made of contrasting printed wax fabric.16 Traditional motifs are sometimes digitally enlarged, reconfigured, or used as graphic backgrounds for modern pieces—an approach well documented in research on West African fashion designers (Figure 5).15,21

Figure 5 Modern Lépi silhouettes on the runway.

Source: Garoua Fashion Week, by Hamza Fakil, 2023

(Indigo Lépi top blending urban tailoring, Fulani identity, and artistic expression.)

Recent studies suggest several contemporary stylistic approaches to enhance the expressive potential of Lépi. These include the use of volume, such as cap sleeves, gathers, and draping, which highlight its suppleness;23 reimagined color palettes like deep indigo and off-white tones, increasingly favored in haute couture;24 minimalist cuts including straight dresses, mandarin-collar jackets, and A-line skirts that take advantage of the fabric’s striped structure;15 and narrative silhouettes where each creation becomes a vessel of memory and cultural transmission.21,25

Thus, the stylistic proposals surrounding Lépi reflect a desire to construct a distinctly African textile grammar—one that is both rooted in tradition and open to innovation. These approaches draw not only on the material properties of the fabric but also on the profound cultural significance of its origins.

Economic, symbolic, and creative stakes of Lépi in contemporary fashion (Cameroonian and African Contexts)

Beyond its aesthetic potential, the repositioning of Lépi within contemporary fashion raises significant economic and cultural issues for artisans, designers, institutions, and textile markets across Africa, particularly in Cameroon, where similar fabrics are produced in the northern regions by Fulani, Kotoko, and Toupouri communities.

A textile value chain with strong local impact

The development of an ecosystem around Lépi, from cotton cultivation to garment production, could stimulate a locally embedded economy. The traditional textile sector employs a predominantly female workforce involved in weaving, dyeing, and sewing. In Cameroon, women from the North and the Adamaoua regions continue to sustain these artisanal practices using simple yet effective tools. The Guinean example, where Lépi benefits from a Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) registered by the African Intellectual Property Organization (OAPI), can serve as a model to inspire a similar initiative in Cameroon, helping to structure the value chain and enhance the value of local craftsmanship. By integrating these fabrics into contemporary fashion, Cameroonian designers contribute to the development of a circular economy grounded in sustainability, knowledge transmission, and the creation of locally generated added value.

A lever for identity assertion and cultural diplomacy

On a symbolic level, Lépi represents far more than just a fabric. It embodies memory, social hierarchy, and ritual significance. In Cameroon, it is commonly associated with customary ceremonies held in traditional chiefdoms or during religious celebrations. Its contemporary reappropriation in urban and international contexts such as fashion shows, exhibitions, and museums positions Sudano-Sahelian Cameroonian cultures within broader global dynamics. UNESCO has emphasized the importance of promoting textile know-how as a means of fostering cultural diplomacy and social cohesion (Figure 6).25,26

Figure 6 “Heritage Lines” runway show in Lépi.

Source: Garoua Fashion Week, by Hamza Fakil, 2023 (Silhouette wearing an indigo Lépi top, merging urban tailoring, Fulani identity, and artistic expression.)

Lépi: A driver of textile innovation within the Cultural and Creative Industries (CCI)

Fashion is now a central pillar of Africa’s cultural and creative industries (CCI). According to the African Development Bank, these industries could account for up to 5% of GDP in certain West African countries by 2030.

In Cameroon, the revival of artisanal textiles and the integration of Lépi into fashion incubators and social and solidarity economy initiatives—such as those supported by the Ministry of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises and by GIZ—serve as tangible levers for enhancing this traditional know-how.

To illustrate this potential, we present below a structured value chain of Cameroonian Lépi, outlining the key stages of its transformation from raw cotton to finished garment (Figure 7):

This infographic presents the key stages in the artisanal transformation of Cameroonian cotton through to its valorization in contemporary fashion. It outlines a structured journey from harvesting, spindle spinning, vertical loom weaving, and natural dyeing, to garment making and clothing design. The visual representation highlights the local anchoring of textile production and its potential to align with a sustainable creative economy.

The transformation of Lépi into design objects, capsule collections, or export-ready artisanal accessories meets the growing global demand for authenticity, sustainability, and uniqueness. Through a labeling strategy and short supply chains, Cameroonian Lépi could become a contemporary showcase of Sahelian textile identity.

Lépi, the ancestral fabric of the Sudano-Sahelian peoples, is undergoing a remarkable transition. From its original ritualistic and social role, it is evolving into a medium of contemporary creation, a vector of innovation, and a symbol of cultural pride. This repositioning, grounded in a thorough technical, stylistic, and cultural analysis, demonstrates that Lépi should no longer be regarded as a relic of the past, but rather as a tool for the future.

Through the aesthetic transformations explored—such as its integration into modern cuts, hybridization with other fabrics, and the exploration of minimalist or narrative forms—Cameroonian and African designers are renewing fashion codes while remaining anchored in their heritage. Owing to its texture, lightness, and symbolic depth, Lépi meets the demands of contemporary design and opens the way for a new African textile grammar that bridges tradition and modernity.

On an economic and institutional level, integrating Lépi into creative value chains presents concrete opportunities for revitalizing artisanal textile production in Cameroon. Supported by local initiatives, academic training programs, incubators, and labeling policies, this fabric has the potential to become a symbol of sustainable and culturally embedded textile design, capable of gaining visibility both locally and internationally.

The rediscovery of Lépi by designers, artisans, and researchers is not merely a fashion phenomenon, but a strategic act of cultural reappropriation. It represents a true societal project in which heritage becomes living material, shared innovation, and a driver of local developme

The authors express their sincere gratitude to Hamza Fakil, dedicated fashion designer and key figure of the Garoua Fashion Week, for providing visual content and for his valuable support during the field study. His work, blending contemporary creativity with the valorization of Fulani textile heritage, has grounded this research in a living cultural and aesthetic reality.

We also extend our thanks to the GIZ – Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit, for its continued support through the ProCoton program, which contributes to the sustainable revival of the cotton sector and the promotion of local know-how in Cameroon.

None.

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

©2025 Ndogmo, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.