Journal of

eISSN: 2574-8114

Research Article Volume 10 Issue 1

1Clothing and Textile Technology Department, Cape Peninsula University of Technology, South Africa

2Fashion & Surface Design, Cape Peninsula University of Technology, South Africa

Correspondence: Anelisa Harmony Sontshi, Clothing and Textile Technology Department, Cape Peninsula University of Technology, Symphony Way, Bellville Campus South Africa

Received: January 26, 2024 | Published: February 12, 2024

Citation: Moyo D, Chisin A. Fit satisfaction and experiences of plus-size females with active-wear in Cape Town, South Africa. J Textile Eng Fashion Technol. 2024;10(1):41-47. DOI: 10.15406/jteft.2024.10.00364

The increased level of health awareness globally has resulted in growing numbers of consumers participating in sports activities to achieve a healthier lifestyle. However, a significant number of active plus-size females face challenges in finding attire or active-wear that fits properly and is engineered to ensure predefined performance requirements. The aim of this research was to investigate plus-size women’s experiences regarding fit satisfaction levels, and their perceptions about active-wear to improve fit, functionality, and clothing aesthetics. The study sought to establish plus-size female experiences regarding fit satisfaction levels, clothing choices and alternatives, including perceptions around aesthetics and purchasing behavior pertaining to active-wear offered by local clothing retailers in Cape Town. A mixed qualitative method was employed with 38 participants aged between 18-46 years, who self-identified as plus-size. The findings from the data revealed that the needs of plus-size women are not understood nor recognised regarding active-wear. The research indicated that plus-size females feel excluded by the clothing industry; they often resort to purchasing unsuitable exercise gear because of limited choices that suit their body shape needs. The finding results were used to develop practical improvements of active-wear for plus-size females, where innovative ideas were developed to address the technical issues of problems identified in the survey.

Keywords: active-wear, plus-size women, fit, sizing systems, body positivity, functional garment, comfort, universal design principles

The use of active-wear apparel such as tights, tops and sport bras are specifically designed to be worn when one participates in any physical activities. Active-wear is not only worn for sporting activities, but for everyday fashionable use as well. The function of active-wear allows for freedom of movement, is light in weight, regulates body temperature and manages moisture in a variety of body shapes and constructions based on different functional materials that meet specific needs.1 A significant number of plus-size females are active in gyms to keep healthy by exercising. Finding active-wear that fits properly and is engineered to ensure predefined performance requirements is a challenge for plus-size females.

According to Christel, O’Donnell and Bradley,2 plus-size females face challenges when buying clothing, ranging from price discrimination, limited choices, fit satisfaction and an overall discouraging shopping environment. These full-figured women are increasingly aware of the variety of clothing that exists in the market but supplying larger women with these clothes is increasingly problematic (Veinikka, 2015). Even while this segment has been the fastest growing in the fashion industry over the last few years, there is a need for companies to reconsider the variations of active-wear and the offerings available to bigger females.3 There is a gap in the clothing and textile market that addresses availability, perceptions and fit satisfaction level of plus-size females regarding active-wear.4 The focus of this article is to address this gap as studies about fit satisfaction of plus-size women are limited in South Africa.4,5

Literature review

Plus-size females

The term plus-size is widely used by the majority of clothing retailers in the clothing industry and in society in general. According to Deborah et al. (2020), the average American woman – including White, Black and Mexican women – wear sizes between 16 to 18 which are categorised as plus-size. In South Africa, the average woman wears a size 18.6 Parameters that define and classify plus-size are unclear, but the phrase is derived from words such as fat or obese (Dunn, 2016).7 Consequently, the criteria which the researcher is using to categorise plus-size females is size 18 above, as the study is addressing issues related to full-figured females.8 In this study the criteria that was used to select plus-size women it was a self-identifying criterion to see how women categorised themselves to get an average from which size to categorise plus-size. Based on the qualitative online survey women who wear size 36 and above participated in this study because they stated that because of their body shapes mostly women who have wider hips and larger buttocks with small waist and bigger breast also experience fit challenges with active-wear available in clothing retailers. Therefore, according to this study plus-size women who wear size 36 and above are categorised as plus-size.

Body positivity image (plus-size women)

According to Leboeuf9 body positivity refers to the movement where plus-size women accept their bodies regardless of size, shape, gender and physical abilities. This body positivity movement is important because it is helping to change the way society views plus-size women. Plus-size women can be healthy and beautiful, and they should be celebrated for their unique bodies.10

The body positive movement is breaking down barriers that have been preventing plus-size women from full acceptance in society as well as rejection from the clothing industry.9,10 This research is contributing to this movement by embracing plus-size women, boosting their confidence where inclusive active-wear prototype designs were developed to accommodate their needs, to make them feel beautiful, strong and amazing with active-wear that fits their curves properly.

Active-wear

Sportswear can range from clothing worn by professional players to active-wear worn by everyday people for exercise or fashion value.11 According to Bhattacharya and Ajmeri,11 as more people adopt healthier lives, more sports have been developed, many traditional sports have grown in popularity, and many more individuals are participating in a wider array of physical activities, including plus-size women.

Active-wear refers to clothing items worn for individual sports, fitness lifestyle promotion or for daily activities such as leisure and comfort.12 In the last half-century, active-wear has trended as a fashion item worn daily. However, finding active-wear apparel that is properly fitting and appropriately accommodating the bodies of plus-size females is a challenge (Pisut, & Connell, 2007; Bickle et al., 2015; Dabolina et al., 2018).2,13

Sizing standards in the apparel industry

The South African ready-to-wear clothing sizing system was developed based on an ideal Western body shape, such as the use of the British anthropometric system by some garment manufacturers (Bobie, 2022).5,14 However, women’s clothing sizing is not standardised, and many brands use different sizes to accommodate their target market. The lack of a uniform sizing system by clothing retailers affects the fit for plus-size women (Brown & Rice, 2001). According to Pandarum et al.5 and Cooke,6 the average size of South African women is plus or ‘curved’, with a bigger bust size, smaller waist and bigger hips. According to Huyssteen (2006) and Strydom (2008), if body measurements of the population are not accurate, all other aspects such as pattern construction, sizing systems and fit will not meet the acceptable standards or proper fit. Seen from this perspective, the South African sizing system is outdated as most clothing retailers adopted and then adapted to a European sizing system. Therefore, it is essential that garment sizing be updated to meet the demands of contemporary consumers.15

The most common system used by clothing retailers catering specifically for plus-size females is a system called vanity sizing. Here, retailers manipulate the sizes, making bigger sizes look like smaller ones to fool women into believing they are wearing a smaller size. This vanity sizing system creates confusion and difficulties for consumers to find the right size or proper fit in stores.16,17 Current sizing systems, which differ from country to country, from shop to shop, and even from one manufacturer to another, have resulted in a wide size variation in the market. The poor sizing systems used by clothing manufacturers create more fit problems, as consumers must try garments on before purchase, or alter the garment before wearing it to ensure that fit is acceptable (Labat & DeLong, 1990). Factors such as size, comfort, functionality, end-use, price and style play a major role in making purchase and wear choices.

Perceptions of plus-size females

There are very few studies investigating females' perceptions about clothing fit, consumer experiences and issues regarding customer satisfaction with sizing in South Africa.18 Plus-size female consumers often purchase apparel items that do not meet their fitness requirements or age-appropriate styles or fashion (Bickle et al., 2015). The shapes and sizes of women have been changing while there has been no concomitant change in the sizing standards and garment proportions in apparel industries.19 According to Buttner et al.,18 the fashion industry focuses on fashionable outfits that do not cater for larger sizes, while the average plus-size women globally wear sizes 16 or 18. As a result, many plus-size females experience problems regarding the fit of their clothes. Plus-size females believe that the fashion industry does not understand their clothing needs and their body proportion or shape (Lear Edwards, 2015).18 In South Africa, such studies are not publicised. While some fashion industry houses do individual, ad-hoc surveys, there is an information gap that the academia, such as university research in South Africa, can address through studies of perception, fit satisfaction and emotions felt by plus-size female consumers, and reasons certain emotions affect purchase decisions, wellbeing and self-esteem.20

Plus-size females challenges with fit

Many of the studies that address fit satisfaction and consumer experiences of plus-size women report that in most cases women globally cope by cross-dressing when they purchase clothing.2,21 Cross-dressing is when women purchase clothing items designed for the opposite gender.2 Another issue is that plus-size females find it difficult to get the clothing they prefer with the insufficient choices in styles that accommodate certain body types. The use of different sizing systems by clothing retailers is affecting the fit of clothing for women in general, but especially for plus-size females as they feel excluded when it comes to style variety and choice in their preferred clothing: most styles are designed for small customers.14,16

Clothing comfort and functionality of garments

Fit is one of the important factors that influences clothing comfort and garment functionality. According to Runfola and Guercini,22 garment fit refers to how well a garment conforms to a person's three-dimensional body. A comfortable fit is one of the major elements considered in the selection of active-wear. This is because the functionality of a garment is determined by the correct size and consumers use garment fit as means of evaluating the quality of the garment.23 Proper fit means the garment does not restrict the movements of the wearer while exercising. Every woman develops her unique style and set criteria with which to evaluate the fit satisfaction of any clothing item, and clothing needs to fit the body of the wearer regardless of size or body shape.2 Hence, comfort is felt by the body in terms of movements during physical activities and depends on the individual (Pisut & Connell, 2007; Dabolina et al., 2018).2,13

Different body shapes (figure forms)

According to Alexander et al.,24 there are four main female body shapes identified within the apparel industry: the hourglass shape, the rectangular shape, the pear shape, and the inverted triangular body shape. Not surprisingly, the inverted body shape has the highest level of satisfaction in terms of garment fit.24 According to research from the University of Pretoria and Tshwane University of Technology, most women in South Africa are pear-shaped.25 Figure 1 is the plus-size women who volunteered to participate in the practice-led study and their body shapes support that indeed most women is South Africa are pear shaped.

Clothing retailers are importing 70% of their clothing items to cater primarily to an hourglass shape. According to Pandarum et al.,5 South African clothing manufacturing is very small and accounts for only 3% compared to other clothing manufacturing companies in other countries such as China. Most South African clothing retailers source clothing internationally to meet the current need for fashionable women’s apparel. Researchers further discovered that “as there are no reports of clothing sizing and fit comparing South Africa and China which is dominating in South Africa in clothing, the hypothesis is that the apparel is not necessarily manufactured for the current body shapes and sizes of South African women”.5 Poor apparel sizing and ill fit are still an everyday reality for many women today (Vladimirova et al. 2022).16

Concept of universal design

Park et al.26 define universal design as products that are designed to accommodate individuals’ needs to the greatest extent possible, without the need for modification or specialised design. In clothing, only a few empirical cases have applied the concept of universal design to their design practices (Carroll & Gross, 2010; Carroll & Kincade, 2007, cited in Park et al.,26). The concept has, however, been used widely by various other design disciplines, such as product design, to better the performance of the artefact to meet the needs of those who have been excluded or denied access by inappropriate design.

The term universal design has been used by other authors interchangeably with words such as inclusive design (Carroll, & Gross, 2010; Patrick & Hollenbeck, 2021),27 as they introduce design approaches that are inclusive and barrier-free – approaches that are also explored in this research. Since Park et al.26 emphasise the absence of principles of universal design in the apparel field, this study explored seven principles – equitable use, flexibility in use, intuitive use, perceptible information, tolerance for error, low physical effort, size/space for use – and where appropriate, to help address design problems with active-wear apparel for plus-size females. Chauhan et al.,28 explains that consumers develop a bond with clothing items they buy, during use, and after use. As clothing items become part of one's identity, it is essential for researchers to constantly improve the fit of clothing apparel to suit and reflect individuals' sense of style and preference. Most importantly for this study, active-wear must conform to a person's physical individuality regardless of age, weight, and body shape, and must meet the functional needs of plus-size females.

A qualitative method of survey29 and practice-led research method (Niedderer, 2021) were employed using purposive sampling to address the primary goal of this study. Females who regarded themselves as plus-size were recruited through social media platforms. The researcher approached the participants in her own WhatsApp contacts by posting an invitation poster. Plus-size female participants were asked to participate and complete an online survey voluntary and to share the survey link on their social media platforms. A structured, open-ended, and Likert-scale questionnaire using Google forms was used to collect the data. The initial sample size was 22 plus-size females, the researcher obtained 38 responses. Even though the use of active wear is shifting to leisure, everyday wear, it was important that the participants be involved in at least one physical activity to ensure that active-wear is purchased and used at some point for the purpose of exercising.

Interview structure in the online survey

A structured, open-ended, and Likert-scale questionnaire was employed for the qualitative online survey data collection. The survey was created on Google forms, on Google drive applications. The survey used five Likert scale questions and seven open-ended questions to ensure that the responses are standard and be able to answer the research question. Social media platform was chosen because it was to use, and it was sustainable. To rate the overall fit satisfaction or active-wear as (1) bad (means they are not satisfied), (2) poor, (3) moderate (or, neutral), (4) good or (5) excellent (means they are satisfied with the fit of active-wear). The researcher also prepared consent forms that were distributed to the participants prior to conducting the survey. The respondents were from Cape Town, South Africa. Open-ended questions allowed the respondents to share their concerns about active-wear currently available on the market. This study was able to obtain valuable data about fit and the experiences of plus-size females with sizing, comfort, performance, fabric choices, style preference, recommendations, and suggestions regarding current active-wear for the fuller figure. This data subsequently influenced in the process of designing and developing prototypes to improve the fit of active-wear in this category.

Ethical clearance was granted by Ethics Committee to the researcher before proceeding the online survey. The explanatory statement was provided for plus-size females who then signed consent letters to indicate that participation in this research was voluntary. Face to face was organised in the process of practice-led study for Anthropometric 3D body scan and the fitting sessions of the prototypes at Cape Peninsula University of Technology, Clothing and Textile Department.

Practice based research

The practice-led research component consisted of a garment comparison study of current, commercially available active-wear apparel: leggings and tops. Following anthropometric body measurement scans30 of two plus-size female participants, and fabric selection and textile laboratory testing, the design and development of the active-wear prototypes were executed. The methodology of executing this research was important to obtain reliable information.

For practice-led study, the researcher explained the process and the selection of the participants so that they can be prepared and know what is required to participate in this part of the research.

The researcher has followed the design development phases used in clothing manufacturing.

Phase 1: Active-wear garment comparison from Stores A, B and C.

Part 1 – Analysis of store leggings without the participants wearing them.

Part 2 – Analysis of three pairs of leggings when they are worn by the participants.

Phase 2: Anthropometric data – collection of body measurements from plus-size women for the use of developing a prototype using a 3D body scan. Four participants were asked to volunteer in the design development process of the prototype with the aim of analysing different body shapes of plus-size females. Participants were invited to come and undergo an anthropometric 3D body scan at CPUT Clothing & Textile Technology Station as it was discovered that this process is more accurate to measure participants using an anthropometric 3D body scan. These measurements were then used to construct patterns of active-wear.

Phase 3: Construction of legging basic blocks and fittings

Patterns blocks are constructed following the book Metric Pattern Cutting for Women’s Wear, and adaptions will be made from this block during the styling process as the book states that there is no ease for comfort or movement. The legging blocks are constructed from the Metric Pattern Cutting for Women’s Wear as well. Pattern adaptions from work-plan to final patterns are constructed and tested and pattern adjustments are made.

Phase 4: Presentation of the legging basic blocks

Fitting sessions of the legging basic blocks with plus-size female participants before the design development the final prototype range.

Phase 5: The styling of the prototype range

The designing and pattern construction process of four leggings and matching tops.

Phase 6: Fabric selection for the styled patterns (final prototypes)

Fabrics were sourced from local suppliers in Cape Town. Fabrics were tested for fabric stretch and high-performance fabrics for comfort such as breathability of the materials. All fabrics used for the protype were tested at the CPUT Clothing & Textile laboratory.

Phase 7: Presentation of the technical drawings of final products (prototype range)

The researcher used Kalido Style software to construct technical drawings of the final prototypes.

Phase 8: Assembly process of the prototype

Specialised fabrics and threads were sourced locally to design this prototype. For the sewing process of the prototype, specialised machines used for this production include the mock safety four thread overlocker, plain stitch machine and cover seam machine.

Phase 9: After the assembly process, three participants were asked to test and evaluate these samples. Feedback from the participants was discussed in the research findings.

The prototype was developed by adopting universal design principles and considering different body shapes. Categories were developed based on respondents with a big bust and smaller hips and plus-size females with a big bust, tiny waist and big thighs, for example. Data is valuable since it may practically and clearly demonstrate the differences between what is available on the market for plus-sizes and the expectations of plus-size females regarding fit satisfaction levels.

Data analysis

The data was analysed in consultation with a professional statistician. Qualitative data were analysed using Excel using descriptive statistics and frequency distribution bar charts and tables.

Demographics

The target population for this study consisted of 38 plus-size females only between 17 and 46 years of age who are based in Cape Town, South Africa. The graph in Figure 2 is presenting the ages mostly participated in the study and Figure 3 is presenting 90% of plus-size women were African group.

Online survey findings and discussion

Section A: Likert scale plus-size women shopping experience

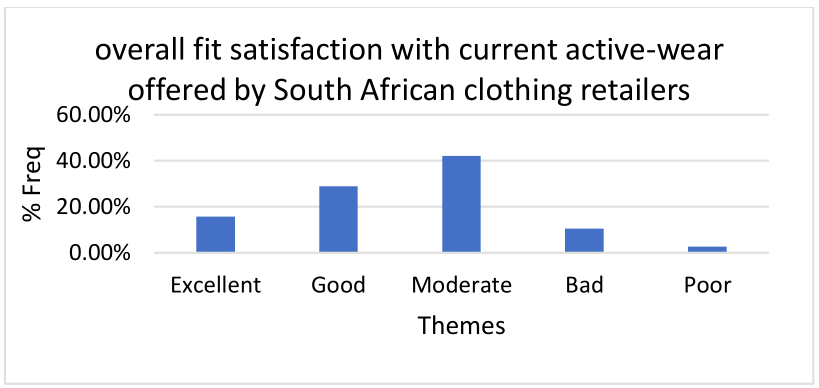

Figure 4 is a bar chart presenting the responses from the participants, with 42.11% of plus-size as neutral because they mentioned that active-wear is available in the market; however, they often purchase items and ask local designers to make alterations for them.

Figure 4 Overall fit satisfaction with current active-wear offered by South African clothing retailers.

Graph B: plus-size females were rating tops with 13.2% of plus-size women were somewhat unhappy with the tops they purchase; 39.5% were neither happy nor unhappy; 23.7% were somewhat happy; and 23.7% were very happy. As mentioned in 4.1 in the introduction, the researcher will be evaluating and analysing leggings only. Tops will be designed and sewed only for the presentation of the prototype (Figure 5).

Graph C: plus-size females rated sport bras with 18.4% somewhat not happy with the fit of sport bras; 39.5% neither happy nor unhappy; 21.1% somewhat happy; and 21.1% very happy with the fit of sport bra. Also, this clothing item is not going to be designed; but it will be discussed in future studies.

Graph D: the participants rated the overall shopping experience when plus-size females are shopping for active-wear. About one fifth (18.4%) of plus-size females were not very happy with the shopping experience; 26.3% were somewhat not happy; 31.6% were neither happy nor unhappy; 15.8% were somewhat happy; and 7.9% were very happy with shopping experience.

Section B: Open-ended questions

Plus-size women willingly shared their personal views about fit satisfaction level of current active-wear. They expressed their challenges from which the researcher captured themes from their responses where they identified fit, comfort, garment performance, bodily area of garments where they find garments are restricting them from performing well during physical activities, fabric used and incorrect sizing. The bar chart below shows the themes which emerged drawn based on the perceptions of participants.

Plus-size women face an array of challenges when shopping for active wear. Bar chart below presents the garment areas which plus-size women find problematic. The researcher created guidelines for the participants from which to identify specific challenging areas with active-wear.

Suggestions to improve fit of active-wear for plus-size women

The bar chart presents the suggestions made by plus-size women for improving active-wear in the future. 33% of plus-size women suggested that there is a need to improve the sizing systems used in South Africa. This feedback is evident that indeed the need to study South African body shapes will results to accurate sizing. 14% of plus-size women suggested that the fit of current active-wear requires improvements as well as the style that is offered to plus-size females. 12% of suggested to improve on selection of fabrics used for active-wear, to be flexible and provide required performance during the workout. 10% of plus-size women highlighted comfort of the wearer should be considered, 7% suggest there is a need to study South African body shapes, and lastly 8% suggested that plus-size models should be used by retailers to get accurate size and a proper fit on clothing that is offered to plus-size.

The researcher explored and further investigated fit of active-wear by designing a prototype. From the suggestions that were proposed by plus-size women on how fit of current active-wear can be improved, the researcher incorporated universal design as products should be designed in such a way that they accommodate an individual`s needs to the greatest extent possible (Table 1).26

|

Equitable use |

The use of the accurate body measurements of Participant Z2 and Participant T1 were used to construct patterns of the prototypes. Fit was tested and pattern adjustments and alterations were made. |

|

Flexibility in use |

Fabrics were tested in CPUT textile lab to check the quality, comfort, and performance of the fabrics. The fabrics passed the tests and are approved as suitable for the active wear. |

|

Perceptible information |

The fabric colours were selected to produce a vibrant and stylish range. Participants rated the style ‘5’ which means they are very happy. The prototype is motivating and boosting confidence of plus-size women. |

|

Tolerance for error |

Fabrics are tested for fabric performance, such as stretch and recovery, seam strength, and dimensional stability shrinkage % was -1% and stretchability % was + 0.75% which means it meets the tolerance for error. Pattern adjustments and second fit of the final prototype to suit the fabric type, and to fit perfectly to the plus-size female body. |

|

Low physical effort |

Final prototypes were tested by the plus-size female participants. Physical activities or movements was a requirement to test the performance of the prototype garment design, comfort as well as the fit in terms of the measurements that were used. |

|

The results were positive: the garment design and elasticated waistband passed the test, preventing the waist from rolling down. The materials were flexible and not restricting the wearer. |

|

|

Size/space for use |

Plus-size women’s accurate body measurements were used to accommodate their size and body shape. |

|

Intuitive use |

Prototype design development has met the requirements of the garment manufacturing process; leggings basic block was constructed as the base foundation before styling the garment. Two fitting sessions were conducted to test and refine the fit of the leggings. |

|

Master patterns which are the styling of the leggings was constructed after the leggings basic blocks was altered and adjusted to perfectly fit the plus-size women’s body. |

|

|

The final prototype is presented. The garment design on the first fit was rated ‘5’ which means the participants were very happy with how the garment fits to their body. |

|

|

The fabrics also was rated ‘5’ because it meets the performance standards. The overall rating of the prototype range was rated ‘5’ because participants were very happy with the garment design as well as fabrics used. |

Table 1 Analysis of the inclusive prototypes adopted form the universal design principles26

Limitations

To achieve the primary aim of this research, it was necessary to involve a wide spectrum of the South African manufacturers and retailers currently offering plus-size active-wear for women. However, due to time constraints and ethical requirements to conduct this study, there was little time to acquire consent forms to involve experts from the manufacturers producing active-wear. In the recruitment processes, the researcher chose to select participants but had a limited number of respondents as others who could potentially contribute are not on social platforms. Also, the researcher aimed to get participants from diverse cultures, but again, due to limitations encountered in the recruitment process, it was challenging to find different ethnic groups. As data related to this topic is not available in South Africa, this resulted in a limited review of literature.

One of challenges the researcher also encountered while conducting the survey was that most women had difficulty opening the link that was sent by the researcher on their phones. The researcher was delayed completing the sewing process of the final prototype products due to the delay in receiving the fabrics from the supplier. Also, due to financial constraints, the researcher could not conduct the second fit evaluation of the final product to further improve the fit of these active-wear prototypes. However, this research has opened a platform for other researchers to further explore this area of study, by analysing factors affecting fit of plus-size active-wear and contributing to the extensive development of an appropriate Afro-centric size chart for South African women.

The first recommendation is that active-wear manufactures/retailers should start offering plus-size options for plus-size women because currently the choice is limited. In this way, plus-size women could find the right active-wear that would improve performance and comfort as well as boosting their confidence. Another recommendation is to use higher quality materials in plus-size women's active-wear. This would make active-wear more comfortable and last longer, it would improve the performance and fit of plus-size women's active-wear.

Another recommendation is that the clothing industry and local designers should collaborate and study plus-size women body shapes to develop accurate sizing standards that will then be employed to design inclusive active-wear.

None.

There is no any form of conflict of interest about this research work.

©2024 Moyo, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.