Journal of

eISSN: 2574-8114

Research Article Volume 11 Issue 3

Department of Mechanical Engineering, Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology, Bangladesh

Correspondence: M Mahbubur Razzaque, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology, Dhaka-1000, Bangladesh

Received: June 05, 2025 | Published: June 25, 2025

Citation: Razzaque MM. Effect of fabric parameters on the friction of woven fabrics with human forearm skin. J Textile Eng Fashion Technol. 2025;11(3):144-151. DOI: 10.15406/jteft.2025.11.00416

Experiments were conducted with four cotton-based fabrics to determine friction against human skin under different wetting conditions and loads. The friction of mixed fabrics is higher than that of 100% cotton fabrics. On both water-wetted and cream-treated skin, the friction of the fabrics is approximately 1.5 to 2 times greater than that on dry skin. Hygroscopic fabrics experience higher friction when the tension is increased. Friction decreases with increasing tension in fabrics where the picks per inch (PPI) exceed the ends per inch (EPI). On cold cream-treated skin, friction is not significantly affected by the tension in tightly woven fabrics.

Keywords: friction of woven fabrics, tribology of human skin, clothing comfort, fabric parameters, biotribology

Human skin is a delicate biomaterial characterized by its nonlinear viscoelastic behavior. Its friction behavior strongly depends on the contact condition. Adhesion is considered to be the main source of friction of human skin. Deformation mechanism also plays a minor role.1–3 Dry skin is characterized by relatively low and pressure-independent friction coefficients like dry friction of rough solids. However, wet skin shows high friction coefficients that strongly increase with decreasing contact pressure and are affected by the shear properties of wet skin. Ambient temperature, relative humidity, amount of hair present on the skin, hydration of the skin and skin temperature have been reported to influence the coefficient of friction of skin.4 Sweating alters the frictional characteristics of skin. It is found that the friction increases, up until a certain level of sweating and then decreases.5 At a low surface roughness, the skin friction is not affected by the roughness of the contacting surfaces. However, with increasing roughness, the friction increases linearly up to a point after which the friction does not vary much with increasing surface roughness.6 With load, skin friction significantly increases in the low-pressure regime. After a critical value of pressure is reached, the coefficient of friction of skin becomes mostly insensitive to contact pressure.7

Cold creams are widely used for skin treatment as well as for improving the quality of skin. A thin coating of cream on the skin surface can bring drastic changes in the frictional and tactile properties. Tang and Bhushan,8 Tang et al.,9; Tang et al.10 and Ding and Bhushan11 thoroughly investigated the adhesion, friction and wear characteristics of both dry skin and cream treated skin using atomic force microscopy. The cream treated skin has a larger real contact area than dry skin, which results in a larger coefficient of friction. It has been shown that the coefficient of friction and adhesive force decrease as the cream film thickness decreases.

Friction between fabric and skin has long been used as an important quality control parameter in the study of clothing comfort and in the research and development of sport and medical fabrics. Bueno et al.12, Vassiliadis and Provatidis,13 Su and Li14 and Mondal et al.15 investigated the structural characteristics of different types of textile fabrics and different finishing processes for improving clothing comfort. Friction between human skin and fabrics is affected by numerous factors; like, the fiber properties, fabric type, location and age of the skin, skin wetting, etc. The influence of friction on the perception of clothing comfort has been studied by Gwosdow et al.16 in different environmental conditions with six fabrics made of different natural fibers. They found that the skin wetting increases skin friction and decreases the comfort of clothing in hot humid environment. Kenins17 has shown that the skin friction is more influenced by the wetting of the skin than the fiber type or the fabric construction parameters. Fabric-to-skin friction with glabrous skin is less affected than hairy skin when the skin is wet. Therefore, prediction of comfort based on touching a fabric may not be a reliable measure of clothing comfort. The relation between the friction and the tactile perception of textile fabrics was also studied by Bertaux et al.18 and Ramalho et al.19 using both knitted and plain woven fabrics made of different types of natural and manmade fibers.

Darden and Schwartz20 investigated the tactile attributes of polymer fabrics which are used in clothing as well as in protective wound-care products. They observed that the friction between fabric and skin is highly dependent on both material type and fiber geometry. But they did not find any clear indication of how friction coefficient affects the tactile perception of polymer fabrics. Das et al.21 examined the fabric-to-metal surface and fabric-to-fabric frictional characteristics of a series of woven fabrics made of different manmade fibers. Fabric-to-fabric friction was found to be highly sensitive to fabric morphology and rubbing direction, whereas fabric-to- metal friction was found less sensitive to these factors.

Fabrics with high friction may cause contact injuries to sensitive skin. It may cause rash to tender skin of babies and decubitus ulcer in the skin of bedridden patients. On the other hand, medical fabrics for bandage must stick to a particular zone for long time. So, bandage fabrics should have the required amount of fabric-to-fabric and fabric-to-skin friction. Vilhena and Ramalho22 investigated how the friction of medical fabrics varies while rubbing against skin of different anatomical regions under different lubricating (wetting) conditions. The friction of their reference medical fabric against skin was affected by the skin anatomical regions and skin lubricating conditions. For all body regions, the average friction coefficients of wet skin exceeded those of dry skin by a factor of more than two, with the friction increasing with the moisture content. After spreading vaseline on the skin, the friction coefficients were always found higher than those of dry skin, but lower than those of wet skin. In a related work, Gerhardt et al.23 measured the friction between the inner forearm and a hospital fabric in the dry skin condition and in different levels of wetting. The friction coefficients against skin for a completely wet fabric was found more than twofold compared to those for a dry textile fabric. Variation in skin wetting causes change in the mechanical properties and surface topography of human skin, leading to skin softening and increased real contact area and adhesion.

In the context of prevention of contact injuries of skin, Schwartz et al.24 investigated the effects of wetting by sweat, urine and saline on the resulting friction coefficient of skin against different medical textiles. They used porcine skin for physical measurements and concluded that wetting accelerates contact injuries by increasing the friction between the skin and the medical textile, whatever the type of liquid is. Rotaru et al.25 conducted in vivo friction experiments with human forearm skin in their work for developing hospital bed sheets optimized for the prevention of decubitus ulcers. Derler et al.26 have shown that the order of magnitude of the ratio of real and apparent contact areas between textiles and skin is 0.02 ~ 0.1 and that surface deformations, i.e. penetration of the textile surface asperities into skin range from 10 to 50 μm. In order to meet the increased need for evaluating the characteristics of friction of fabric surfaces, several techniques have been introduced. These include introduction of various types of friction measurement systems,27 artificial fingers,28 surrogate skin (Lorica soft),29 tactile stimulator,30 etc.

Most of the researches focused on medical injuries and dealt with special fabrics and special skin areas of medical interest. Though some of them considered woven fabrics, none of them studied how the fabric parameters affect the friction between human skin and woven fabrics, especially when the skin is either wet or treated with cream. This paper presents an experimental study of the friction coefficients between human forearm skin and different types of woven fabrics. Tests were conducted with dry skin as well as wet skin. Wetting was done in two ways. In the first case, the forearm was washed with water, and the excess water was wiped off with tissue paper before conducting the friction experiments. In the other case, cold cream was applied to the skin before the experiments. The friction coefficient data for different skin conditions and fabric parameters were compared and analyzed. It was found that the friction coefficient is strongly influenced by both skin condition and fabric parameters.

Experimental set-up and procedure

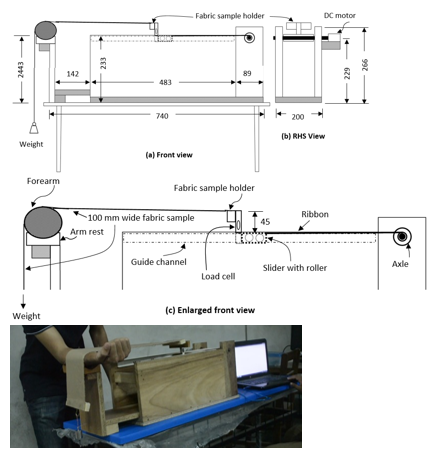

A low cost set-up is developed for the measurement of friction of a fabric sample sliding over human skin. A schematic diagram and a picture of the set-up are shown in Figure 1. In this setup the arm of a volunteer is placed on the armrest and a fabric sample of 100 mm width and 700 mm length slides over the skin of the forearm. Both ends of the fabric sample are reinforced by gluing wood pieces along its full width so that the tensile load is uniformly distributed in the fabric. From one end of the fabric different weights (20 g or 50 g) are suspended so that close contact occurs between the fabric and the forearm skin. The other end of the fabric is attached to a load cell mounted on a slider. A cloth ribbon connects the slider with an axle rotated by a 12V DC motor. As the motor rotates, the ribbon is wrapped around the axle and the slider is pulled horizontally along two guide channels. The armrest is placed at such a height that the fabric sample between the forearm and the slider moves almost horizontally.

Figure 1 (a - c) Schematic diagram and (d) photograph of the experimental set-up (dimensions in mm).

Time required for sliding the entire length of the fabric sample is recorded by a stopwatch and the linear speed is calculated. By repeating this procedure several times, the average value of the linear speed of the fabric sliding over skin was found to be 19.7 mm/s. A 10N (1000 g) load cell connected to an amplifier (Model: HX711) and an Arduino Uno board is used to record the tension in the fabric (T1) in a computer. The load cell and the data acquisition system is calibrated using standard weights. Tension (T2) in the portion of the fabric between the forearm and the suspended load is assumed to be due to the suspended load plus the load of the self-weight of the hanging part of the fabric. Thus, T2 is calculated using the following equation.

(1)

Where, M = suspended dead weight + weight of the wooden support at the end of the fabric to hang the dead weight (g), L = maximum suspended length of the fabric (mm), v = sliding velocity = 19.7 mm/s, t = time (s) and m = mass per unit length of the fabric sample (g/mm).

For the sake of simplicity, the forearm is modeled as a cylindrical body as shown in Figure 2. Then, tensions T1 and T2 on the two sides of the sliding fabric sample can be related to the friction coefficient by the well-known Capstan equation.

(2)

Where, μ is the friction coefficient between the fabric sample and the forearm skin and θ is the contact angle in radian through which contact occurs between the fabric and the forearm. Since the armrest is placed at such a height that the fabric sample between the forearm and the slider moves almost horizontally, the value of θ should ideally be 90o. However, the actual contact angle is slightly higher than this due to sagging in the fabric sample (Figure 2). The contact angle may also depend on the shape and positioning of the forearm. Considering all these effects during the present experiments, the average value of the contact angle was estimated to be 92o ± 0.2o.

Fabric samples

In a woven fabric, two distinct sets of yarns or threads are interlaced at right angles to form a fabric as shown in Figure 3. The longitudinal yarns are known as the warp and the lateral yarns are the weft. One warp yarn is called an end and one weft yarn is called a pick. The number of warp yarns or threads per inch of woven fabric is expressed as Ends per inch (EPI). On the other hand, the number of weft yarns or threads per inch is given by Picks per inch (PPI). The higher the EPI or PPI, the finer the fabric is. English Cotton Count (Ne) is the number of 840 yards (770 m) lengths per pound (0.45 kg) of a yarn. It is an indirect measure of linear density of the yarn; the higher the number, the finer the yarn is. Gram per square meter or GSM gives the weight of fabric in gram per one square meter. The characteristics of a fabric depend on the fabric parameters like GSM, EPI, PPI, Ne and the pattern of weaving.

In the present study, experiments were conducted with four different woven fabrics. Images of these fabrics are shown in Figure 4. These can be divided into two groups. In Group A, two 3/1 Z twill fabrics were considered: Denim 3/1 Z Twill (100% cotton) and Print 3/1 Z Twill (35% cotton + 65% polyester). 3/1 Z-twill fabrics have a rugged twill made by passing the weft yarn over three warp yarns then under one warp yarn and so on, with an offset, between rows to create the characteristic diagonal pattern.

In Group B, two plain weave fabrics were considered: Plain Tent (100% cotton) and Steppe Plain (35% cotton + 65% polyester). In plain weave fabrics, the warp and weft yarns cross at right angles to form a simple crisscross pattern. Each weft yarn crosses the warp yarns by going over one, then under the next, and so on. The next weft yarn goes under the warp yarns that its neighbor went over, and vice versa. These fabrics are specially weaved for long-term use. They should have high abrasion resistance and sewing durability. Typical values of the fabric and yarn properties of the fabrics are shown in Table 1.

|

Group |

Fabric name |

GSM (g/sq. m) |

EPI (Ends Per Inch) |

PPI (Picks Per Inch) |

Warp count, Ne |

Weft count, Ne |

Mass per length (g/mm) |

|

A |

Denim 3/1 Z twill |

437 |

41 |

18 |

9 |

6 |

0.0423 |

|

Print 3/1 Z twill |

222 |

72 |

112 |

20 |

19 |

0.0233 |

|

|

B |

Plain Tent |

377 |

80 |

44 |

44 |

22 |

0.0387 |

|

Steppe Plain |

214 |

112 |

60 |

- |

- |

0.0216 |

Table 1 Properties of the fabric and yarn of the tested samples

Group A fabrics differ from Group B fabrics by their textures and/or weaving patterns. Group A fabrics are 3/1 Z twill fabrics. These are made of coarse yarns (Ne < 20). Group B fabrics are plain weave fabrics. Ends per Inch (EPI) and yarn count of Group B fabrics are higher than Group A fabrics. For all fabrics other than Print 3/1 Z twill, EPI is greater than PPI. Under tension along the warp direction, these should extend less. In case of Print 3/1 Z twill, PPI is greater than EPI. It will extend more under tension along the warp direction.

Experimental conditions

For each of the sample fabrics, tests were done by changing the tension in the fabric and changing the condition of contact between the fabric and the forearm skin of five male volunteers of ~ 22 years of age. Two dead weights (20 g and 50 g) were used as suspended weights to change the tension in the fabric. The weights were chosen so that they are of the order of the self-weight of the fabric samples. Three different conditions of contact have been tested, viz., dry skin, water-wet skin and cream-treated skin. The tests were conducted at room temperature = 25 ± 1 deg C and 60 ± 2% relative humidity. Each of the five volunteers took part in all experiments. The reported data are average of the five measurements from five volunteers.

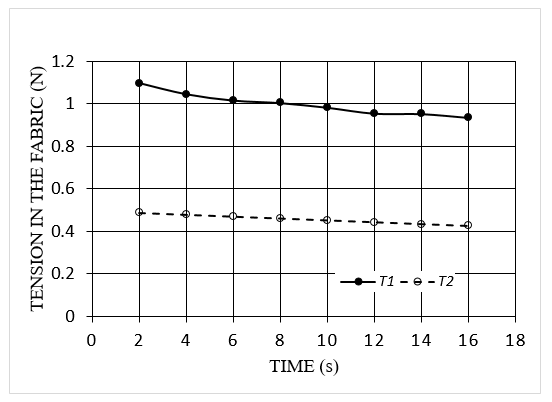

Typical data and results for Print 3/1 Z Twill fabric under tension with 20 g dead weight at dry skin condition are presented in Figure 5. In Figure 5(a), the tension recorded by the load cell (T1) and the tension in the suspended portion of the fabric (T2) are shown as function of time. The value of T2 decreases with time as expressed in eq. (1). The value of T1 is greater than T2 by an amount of force due to the friction between the fabric and the forearm skin. The friction coefficient calculated from T1 and T2 using eq. (2) is plotted in Figure 5(b). It is evident that except for a short starting period, the friction coefficient is fairly constant throughout the test duration. This friction coefficient is kinetic friction coefficient. The small variation seen in the values of the friction coefficient may be attributed to the localized variation in the fabric texture and/or stick-slip phenomena during sliding. The average value of the friction coefficient is determined by repeating the experiment for five times.

Figure 5(a) Tensions T1 and T2 in the fabric under test [Print Z Twill with 20 g load and dry skin].

The range of variation of the friction coefficients determined from similar experiments with different fabrics for different tensions and contact conditions and the corresponding average friction coefficients are presented in Table 2. It may be noted that the formula used in calculating the friction coefficient is derived considering sliding of the fabric over a cylindrical surface. However, experiment using human forearm is not truly compatible with this assumption as the human forearm is not cylindrical in shape. Moreover, the positioning of the forearm on the armrest may slightly vary from one test run to another. These issues should be kept in mind while evaluating the values of the friction coefficients presented in Table 2.

|

Fabric name |

Dead weight = 20 g |

|||||

|

Dry skin |

Water-wet skin |

Cream-treated skin |

||||

|

Range |

Average |

Range |

Average |

Range |

Average |

|

|

Denim 3/1 Z Twill |

0.50-0.42 |

0.46 |

0.82-0.72 |

0.78 |

0.94-0.87 |

0.91 |

|

Print 3/1 Z Twill |

0.50-0.48 |

0.48 |

1.07-0.99 |

1.03 |

0.98-0.94 |

0.97 |

|

Plain Tent |

0.56-0.48 |

0.52 |

0.87-0.80 |

0.84 |

0.96-0.88 |

0.92 |

|

Steppe Plain |

0.57-0.51 |

0.54 |

0.87-0.81 |

0.84 |

0.92-0.86 |

0.9 |

|

Fabric name |

Dead weight = 50 g |

|||||

|

Dry skin |

Water-wet skin |

Cream-treated skin |

||||

|

Range |

Average |

Range |

Average |

Range |

Average |

|

|

Denim 3/1 Z Twill |

0.50-0.44 |

0.48 |

0.96-0.86 |

0.91 |

0.86-0.79 |

0.82 |

|

Print 3/1 Z Twill |

0.58-0.55 |

0.56 |

0.99-0.94 |

0.94 |

0.95-0.90 |

0.91 |

|

Plain Tent |

0.60-0.55 |

0.58 |

1.06-0.89 |

0.98 |

0.97-0.87 |

0.91 |

|

Steppe Plain |

0.65-0.60 |

0.62 |

1.02-0.89 |

0.92 |

0.95-0.91 |

0.92 |

Table 2 Friction coefficient of fabrics for different contact conditions and different tensions (due to different dead weights)

The measured average friction coefficients with dry skin are comparable to those reported by Ramalho et al.19 They used a portable measuring probe with a multi-component force sensor whereby both normal and tangential forces could be measured. The friction coefficient was determined by using the Coulomb friction model. During their experiment in 25 ± 1oC temperature and 59 ± 4 % relative humidity, the normal load was gradually increased from 0 to 1 N with typical sliding speed of 35 ± 10 mm/s. In similar experiments with dry skin of forearm, the average friction coefficients from the current measurement are 0.46 - 0.58 for 100% cotton fabrics, which are close to the friction coefficients (0.55 - 0.60) reported by Ramalho et al.19 The small discrepancy is possibly due to the differences in type and quality of the fabrics and the skin used in the two studies. They have reported a higher friction coefficient (0.68 - 0.72) between 100% polyester fabrics and dry forearm skin. In the current experiments, polyester fabrics contain only 65% polyester. Thus the friction coefficients (0.48 - 0.62) are lower than those reported for 100% polyester fabrics and slightly higher compared to their respective values for 100% cotton fabrics.

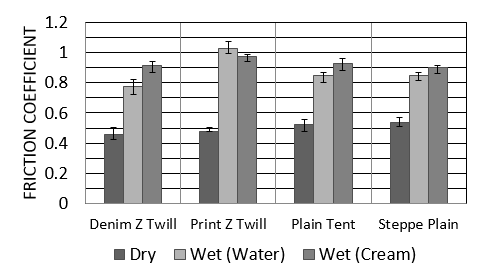

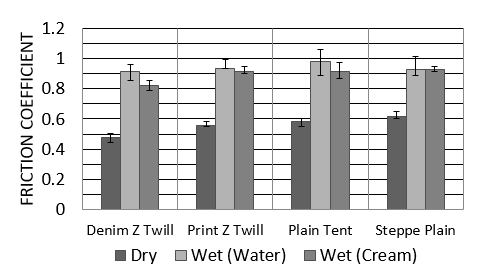

Effect of skin condition

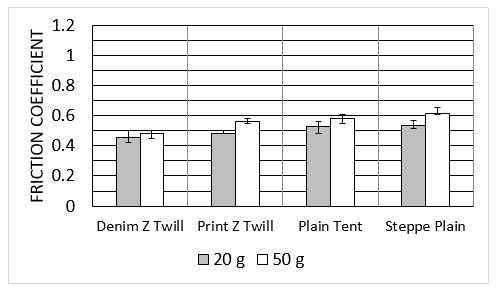

The bar graph in Figure 6(a) shows the average values of the friction coefficient for different contact conditions and different types of fabrics when the fabric is put under tension with 20 g dead weight. The error bars are added to show the range of scatter of the measured friction coefficients. The average friction coefficients for each type of fabrics with three contact conditions are shown side by side in the following order: dry skin, water-wet skin and cream-treated skin. It is clearly evident that the friction coefficients with water-wet skin (0.78 ~ 1.03) and those with cream-treated skin (0.90 ~ 0.97) are relatively close to each other. These values are approximately 1.5 ~ 2 times of the friction coefficients with virgin skin (0.46 ~ 0.62). If the case of Print 3/1 Z Twill is put aside, the friction coefficients are slightly higher for cream-treated skin (0.90 ~ 0.92) than those for water-wet skin (0.78 ~ 0.84). The scenario is different, as shown in Figure 6(b), when the fabric is put under tension with 50 g dead weight. In that case, the friction coefficients for cream-treated skin are 0.82 ~ 0.92 and those for water-wet skin are 0.91 ~ 0.98. For water-wet skin, the increase of tension did noticeably increase the friction coefficients. But for cream-treated skin, the friction coefficients did not increase. Thus, it can be inferred that in developing friction, the condition of the skin (i.e. whether it is dry, water-wet or cream-treated) plays much more dominant role than the tension in the fabric. The friction behavior of Print 3/1 Z Twill fabric is different from the other three fabrics because of its different weaving pattern with high PPI and high PPI + EPI values.

Figure 6(a) Friction co-efficient for different contact conditions and different types of fabrics when the fabric is put under tension with 20 g dead weight.

Figure 6(b) Friction co-efficient for different contact conditions and different types of fabrics when the fabric is put under tension with 50 g dead weight.

Effect of tension and fabric type: dry skin

Figure 7 shows the comparison of friction coefficients of dry skin for different fabrics at two different tensions. It is seen that for all four fabrics tested, higher friction coefficient is achieved when the tension in the fabric is higher. In Group A, two samples of clothing fabrics were taken for study. As seen in Figure 7, the Print 3/1 Z Twill fabric has slightly higher friction coefficient than the Denim 3/1 Z Twill. The composition of Print 3/1 Z Twill fabric is 35% cotton + 65% polyester and that of Denim 3/1 Z Twill is 100% cotton. Skin has more adhesion to polyester than cotton. It is the polyester component of Print 3/1 Z Twill fabric that causes more friction.

Figure 7 Comparison of friction coefficients of dry skin for different fabrics at two different tensions.

When tension is increased, the adhesion as well as the friction is increased for both fabrics. However, the weaving patterns of the two fabrics are affected by the increased tension differently due to their differences in weaving characteristics. The Denim 3/1 Z Twill fabric has coarse ribs of rugged and sturdy construction. It has higher GSM but smaller values of EPI (Ends Per Inch), PPI (Picks Per Inch) and yarn count than the Print 3/1 Z Twill fabric. Thus, compared to the Print 3/1 Z Twill fabric, the Denim 3/1 Z Twill fabric deforms less under tension; causing less change in the real contact area and adhesion. As a result, at higher tension, the increase in friction coefficient is small in case of the Denim 3/1 Z Twill fabric.

Two non-clothing fabrics in Group B are Plain Tent and Steppe Plain fabrics. The composition of Plain Tent is 100% cotton and that of Steppe Plain is 35% cotton+ 65% polyester. As evident from Figure 7, the Steppe Plain with 35% cotton+ 65% polyester gives friction coefficient slightly higher than Plain Tent with 100% cotton. Presence of polyester in Steppe Plain is again responsible for its higher friction coefficient. Under higher tension, the friction coefficient is increased depending on the weaving characteristics of the fabrics. The Plain Tent is made of coarse yarn as it has smaller EPI and PPI but higher GSM (gram per square meter) than the Steppe Plain fabric. It has more sturdy weaving construction. It deforms less and the friction coefficient is less affected under tension.

In head to head comparison between the fabrics of Group A and Group B, latter group possess slightly higher friction coefficient. It may be noted that EPI of Group B fabrics is higher than that of Group A fabrics. That means yarns (warp) are tightly packed in Group B fabrics giving larger area of contact. So, these factors along with the weaving pattern are responsible for higher friction coefficients of Group B fabrics.

The friction coefficient at a given tension is primarily determined by the adhesion between the fabric and the skin. Higher tension affects the area of contact between the fabric and the skin and, hence, the adhesion in two ways. Firstly, it deforms more the asperities on both the contacting fabric and the skin and secondly, it changes the yarn spacing and distorts the weaving pattern. In the first mechanism, the contact area always increases. But in the second mechanism, the weaving pattern determines whether the contact area will increase or decrease. The increase of friction coefficient at higher tension will depend on the resultant change in the adhesion due to change in the contract area between the fabric and the skin.

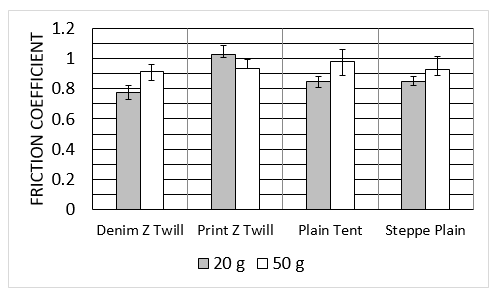

Effect of tension and fabric type: water-wet skin

In Figure 8, friction coefficients of different fabrics for water-wetted contact with skin are shown at two different tensions. It is evident that the change in the value of the friction coefficients in response to the change in tension is more in case of 100% cotton fabrics; i.e. for Denim 3/1 Z Twill and Plain Tent. These fabrics are made of coarse yarns. The change in friction coefficients due to change in tension is less for Print 3/1 Z Twill and Steppe Plain fabrics which contain 65% polyester and are made of fine yarns. Cotton absorbs water, whereas polyester hardly can do it. Due to the hygroscopic nature of cotton, 100% cotton fabrics absorb more water from the skin and get more swelled. Fabrics with 35% cotton and 65% polyester absorb less water and swell less compared to 100% cotton fabrics. When the tension in the fabric is increased, highly swelled 100% cotton fabrics can deform more to increase the real area of contact with the skin. Whereas, fabrics with 35% cotton and 65% polyester swell by less amount and also deform less when the tension is raised. Hence, the increment of friction coefficient at higher tension is more for 100% cotton fabrics than for fabrics with 35% cotton and 65% polyester.

Figure 8 Friction coefficients of different fabrics for water-wetted contact with skin at two different tensions.

However, the behavior of Print 3/1 Z Twill fabrics in water-wetted contacts with skin is interestingly different in two ways. Firstly, it has the highest friction coefficient at low tension. Secondly, at higher tension its friction coefficient decreases whereas for all other fabrics friction coefficient increases. It can be explained by considering the weaving characteristics of this fabric. It has almost similar yarn count in both warp (Ne = 20) and weft (Ne = 19) directions. It has high values of EPI and PPI. The total number of yarns (EPI, 72 + PPI, 112) is the highest among the fabrics tested. On wetting by water, this fabric probably assumes the largest contact area, which is responsible for the highest friction coefficient. However, for all other fabrics EPI is higher than PPI; in this case PPI is significantly higher than EPI. It implies that in this case more yarns are placed in the weft direction, the direction perpendicular to sliding. So, under tension, this fabric should elongate more compared to other three fabrics. The real area of contact due to swelling of the yarns by absorbing water is high in low tension. In higher tension, spacing between two consecutive yarns along weft direction increases. The real area of contact is thus decreased and a smaller friction coefficient is obtained.

Broadly speaking, the friction coefficients are significantly increased by water wetting of the skin. Rotaru et al.25 found similar results in their experiments with hospital bed sheets to find the frictional behavior of fabrics against human skin. When a cotton fabric or a cotton-polyester fabric comes in contact with moist skin, the excess water is practically absorbed by the fabric due to its hygroscopic nature. In addition to that, moisturizing leads to smoothening of skin roughness asperities.3 Thus the real contact area as well as the adhesive force in the contact surface between the skin and the fabric is increased. So, larger amount of force is needed to pull the fabric over moist skin. Consequently, higher friction coefficient results in contact at wet condition.

However, with water wetting, 100% cotton fabrics are swelled more than fabrics with 35% cotton and 65% polyester. When the tension is raised, 100% cotton fabrics deform more to increase the real area of contact with the skin. Thus the tension in the fabrics affects the friction coefficient more for 100% cotton fabrics than for fabrics with 35% cotton and 65% polyester. The friction coefficient may decrease with increasing tension if the spacing between weft yarns in a fabric increases. This is the case with the Print 3/1 Z Twill fabrics, where PPI is higher than EPI.

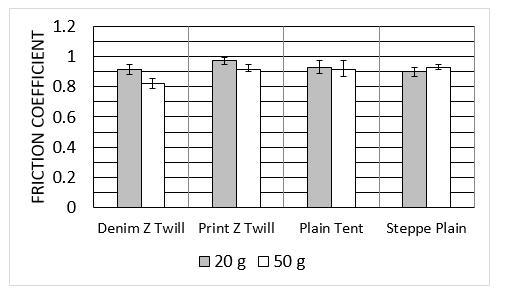

Effect of tension and fabric type: cream-treated skin

Cold creams are semi-solid emulsions generally consisting of water, oil, emulsifier and a thickening agent. The amount of water and oil is approximately equal. It is more viscous than water. When thin film of cream is trapped between the fabric and the skin, only a part of it is absorbed in the skin and the fabric. The remaining part of the cream tends to stick to the contact surfaces filling up the pores in both the skin and the fabric. Friction coefficients for all four fabrics at cream-treated condition and two different tensions are shown in Figure 9. It is interesting to note that for all cases at cream- treated condition, the friction coefficients are found to be around 0.9. This is close to the frictions coefficients for water-wetted contacts (Figures 6a and 6b).

Figure 9 Friction coefficients for all four fabrics at cream-treated condition and two different tensions.

But the nature of variation of friction coefficients in response to the change in tension is different between water-wetted and cream- treated contacts. Unlike water wetted contacts, higher tension in the fabric in cream- treated contacts reduces the friction coefficient for group A fabrics but affects the friction behavior very insignificantly for group B fabrics. At low tension, Print 3/1 Z Twill gives the highest friction coefficient among the four fabrics because of its highest number of yarns in per square inch of the fabric (i.e. highest PPI + EPI).

Group B fabrics are made of coarse yarns and are tightly woven as they have high numbers of EPI and PPI. These fabrics are capable of holding the thin film of cream in their surface. The increase in tension by changing the hanging dead weight from 20 g to 50 g cannot fully squeeze the thin film out of the interface. Thus, the friction coefficient of these fabrics is not changed much by the change in the tension in the fabric.

Group A fabrics are made of coarse yarns as indicated by their yarn counts. Denim 3/1 Z Twill has lower values of yarn count, EPI and PPI compared to Print 3/1 Z Twill. Due to this type of weaving characteristics, Denim 3/1 Z Twill fabric has more pores (Figure 3) and lower contact area. This is why Denim 3/1 Z Twill has lower friction than Print 3/1 Z Twill. When the tension in the fabric is raised, the pores open up more allowing some cream to squeeze out from the interface. This reduces the thickness of the layer of cream trapped between the fabric and the skin causing the friction coefficient to reduce. This finding is consistent with the results of previous studies8–11 where it has been shown that the force of adhesion decreases as the thickness of cream layer decreases.

In this study, the friction coefficients of four types of fabrics were determined against human forearm skin under different contact conditions and tensions. The fabrics used in this work are: Denim 3/1 Z Twill (100% cotton), Print 3/1 Z Twill (35% cotton, 65% polyester), Plain Tent (100% cotton), and Steppe Plain (35% cotton, 65% polyester). The kinetic coefficient of friction for each fabric sample sliding over human forearm skin was measured. Based on the analysis of the results, the following conclusions can be drawn.

In the case of dry skin, the friction coefficient of mixed fabrics (35% cotton, 65% polyester) is higher than that of 100% cotton fabrics for both twill and plain weaves. Fabrics with higher EPI have more tightly packed warp yarns, resulting in a larger contact area and higher friction. A higher friction coefficient is observed when the fabric is subjected to greater tension. This is due to an increase in the real area of contact between the fabric and the skin, caused by greater deformation of surface asperities under higher tension.

Under both water-wetted and cream-treated skin conditions, the friction coefficients of the fabrics are approximately 1.5 to 2 times higher than those under dry skin conditions. When a cotton or cotton-polyester fabric comes into contact with skin moisturized by either water or cold cream, the moisture is absorbed by both the skin and the fabric. This results in a higher adhesive force at the contact surface, leading to an increased friction coefficient. Hygroscopic fabrics absorb more moisture from the skin and swell more significantly. They deform to a greater extent and experience higher friction when the tension is increased. However, the friction coefficient may also decrease with increasing tension if the spacing between weft yarns increases. This typically occurs in fabrics where the picks per inch (PPI) are higher than the ends per inch (EPI).

In cold cream-treated skin, a thin film of cream forms between the skin and fabric surfaces, and the friction coefficient is significantly influenced by the presence of this film at the contact surface. Fabrics with large Ne, EPI, and PPI are tightly woven, allowing the thin film of cream to remain even when the fabric tension is increased. Therefore, in such cases, the friction coefficient is not greatly affected by fabric tension. However, fabrics made of coarse yarns with low EPI have larger pores, through which the cream can easily be squeezed out as the fabric tension rises. This causes both the thickness of the cream layer and the friction coefficient to decrease with increasing tension.

The author is grateful to Mr. Rakibul Islam, Mr. Fahim Foysal, Mr. Sadman Sakief Hridoy, Mr. Nazmus Sakib and Mr. Md. Roman Mia who volunteered in the experiments.

None.

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

©2025 Razzaque. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.