Journal of

eISSN: 2574-8114

Mini Review Volume 11 Issue 2

An independent researcher and curator, graduated from KU Leuven’s Art History department, Belgium

Correspondence: Ebba Van der Taelen, An independent researcher, graduated from KU Leuven’s Art History department, Belgium

Received: February 18, 2025 | Published: March 3, 2025

Citation: Taelen EV. Double activation: the ephemeral interaction between body and jewelry. J Textile Eng Fashion Technol. 2025;11(2):59-62. DOI: 10.15406/jteft.2025.11.00404

Contemporary jewelry is a niche within the applied arts, yet recent years there has been substantial theoretical development in this field. However, a particular category of jewelry has remained underexplored: pieces that actively assert their presence rather than merely adorning the body passively. These 'active' jewelry pieces have not been theorized, a gap I aim to address by coining the concept 'double activation'.

According to Kevin Murray and Rock Hushka, every piece of jewelry becomes ‘activated’ when worn on the body. However, I argue that 'double activation' jewelry also ‘activates’ the body, resulting in a second - 'double' - activation. These pieces induce sensations in the wearer's body that would not be experienced without the jewelry. They achieve this through five mechanisms: (1) restricting movement, (2) interacting with body parts and potentially causing pain, (3) manipulating the body's forms, (4) extend ing the body to generate new sensations, and (5) taking control over the body.

Drawing on examples such as Jennifer Crupi’s Ornamental Hands: Figure One and Akiko Shinzato’s Chin Up, this article explores how these works subvert conventional jewelry’s passive role. These pieces demand a temporary relationship between body and object, where control is relinquished to the jewelry. As such, ‘double activation’ can be seen as a performative event — a brief moment in which the wearer’s body and the jewelry coalesce into a singular entity before the interaction becomes unsustainable.

This ephemeral relationship challenges the notion of jewelry as static and ornamental, proposing instead a conceptual framework where the focus is placed on transient bodily experiences. In this way, ‘double activation’ shifts the discourse on ephemerality in jewelry from the materiality of the object to the temporality of the interaction itself.

Keywords: ephemerality, body-jewelry interaction, performativity, sensory experience, body control

In our daily lives, we demand that the jewelry we wear does not hinder us during activities. If a piece of jewelry continuously bothers or hurts us, we would simply stop wearing it. Therefore, we implicitly assume an inherent passivity of jewelry.1 Pieces hang around our necks, wrists, fingers, but do not assert their presence. If we could physically feel the jewelry we wear, it could be experienced as unpleasant. Many pieces of jewelry, therefore, blend into the skin; they become part of our body.2,3 Consider, for example, a ring that you notice when you slide it onto your finger, but forget throughout the day.3 The ring becomes part of our body, and we ignore the stimuli it sends because, essentially, a ring does not send many stimuli; it behaves passively around our finger.

Within contemporary jewelry art, there is a group of jewelry that refuses to behave passively and instead aims to actively intervene in our physicality.1 These creations do send stimuli to our bodies, which are often experienced as unpleasant. When these pieces are worn on our skin, they make their presence felt, unlike a 'normal' piece of jewelry. Designers of such jewelry desire an ephemeral wearing experience. The ephemerality does not refer to the materiality of the jewelry but to the temporary interaction between human and jewelry. The process that occurs when wearing this specific group of jewelry is what I call 'double activation,' and I will briefly map it out in this spotlight article. Through my theory of 'double activation,' I aim to shed new light on the notion of ephemerality by shifting the focus from material ephemerality to exploring the ephemeral, transient relationship between body and jewelry. Ephemerality does not always pertain to objects and their temporality and materiality but can also refer to the brief moments of ‘reaching potential’, as I will explain in this article.

'Activation' and 'double activation' in contemporary jewelry art

To understand the concept of 'double activation,' one must first understand a process that occurs with all jewelry, namely 'activation.' Every piece of jewelry has an intrinsic link to the body.4 Thus, a piece of jewelry truly becomes 'a piece of jewelry' when worn, as it then actualizes its potential.4 Various authors, such as curators Kevin Murray5 and Rock Hushka,6 refer to this as the 'activation' of the jewelry. Murray5 states that during this process, the jewelry as an object comes to life and becomes functional. Hushka,6 on the other hand, focuses less on the material aspect of activation and claims that the jewelry's meaning only comes to light when worn. At that moment, it can communicate its meaning to the world.6 A jeweler must place their creation on a body for it to become a 'real piece of jewelry' and for its inscribed meaning to reach the world.7 After this activation process, jewelry has actualized its potential but then quickly falls into passivity.

However, with some pieces of jewelry, a second 'activation' occurs. These creations take on an active role and intervene in the body after being placed on it. Therefore, a 'double activation' occurs: first the body activates the jewelry, then the jewelry activates the body again. These creations want the wearer to become aware of their own physicality, as this is something we rarely consider in daily life, according to jewelry designer Sophie Hanagarth.8 They achieve this by evoking sensations that the wearer typically does not experience, thereby prompting a reevaluation of their own body, including its form and functionality. The 'double activation' process occurs by wearing jewelry that:

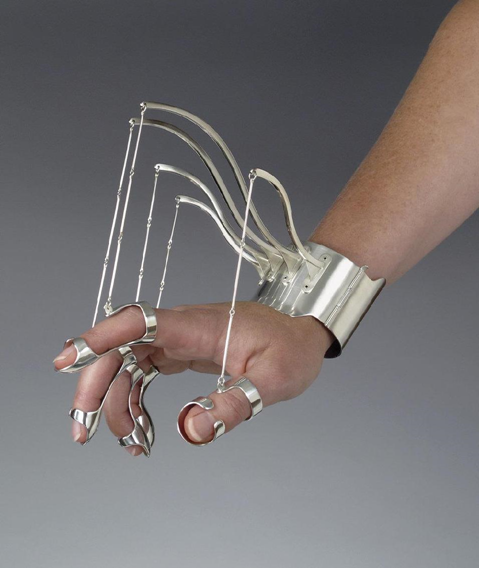

These methods of evoking sensations can occur separately or together. An example that illustrates the concept of 'double activation' is Ornamental Hands: Figure One (2010) (Figure 1) by American jeweler Jennifer Crupi9.1 This piece is a medical-looking brace for a right hand made of solid silver. When worn, the hand can only take on one specific position, chosen by the jeweler. Crupi's creation limits the body's movement possibilities (1) and takes control over our hand movements (5). The chosen position refers to uncomfortable yet elegant hand gestures that appear in paintings by old masters.2 As these gestures are difficult to maintain for a long time, this silver brace helps keep the hand in position. Despite the support this jewelry provides, the hand will cramp over time. Ornamental Hands: Figure One thus also causes pain to the body (2), making the interaction between jewelry and body unbearable and therefore ephemeral. The massive, demanding brace and the soft skin cannot be reconciled, leading to an unsustainable relationship: the body-jewelry entitiy will soon be broken up.10

Figure 1 Jennifer Crupi, ornamental hands: figure one, 2010. Silver, 38,1 x 21,6 x 14 cm.

Washington D.C., Smithsonian American Art Museum, inv.nr. 2013.34A-B. Accessed on March 12, 2023,

The impact of ‘double activation’ on the roles of maker and wearer

Exploring the roles of the maker and wearer in ‘double activation’ jewelry is intriguing.3 Drawing on insights from Liesbeth den Besten, the role of the jewelry maker in ‘double activation’ pieces can be seen as unconventional. According to her, the maker not only shapes jewelry but also the body.2 Take for instance, Chin Up (2018) by Akiko Shinzato from her collection Self-confidence Boosters.4 This brass neckpiece has a single purpose: to hold the wearer's chin up. Shinzato first envisioned the form the body should take and then created the jewelry to fulfill that vision; she shaped both.11,12

Also, the wearing experience of 'double activation' pieces is distinct from experiencing passive jewelry. In ‘double activation,’ the wearer is actually a participant, invited by the jewelry designer to engage in a performative experience.11 Since these pieces typically manipulate, distort, or evoke sensations in the body for only a short period, the act of wearing them can be seen as an ephemeral mini-performance — especially since a body is involved.

Capturing ‘double activation’ jewelry in images

The performative, ephemeral nature ‘double activation’ has further implications, especially regarding the presentation of jewelry. As mentioned, ‘double activation’ jewelry only realizes its potential when worn on the body. The concept behind the piece is fully expressed only in situ, but since wearing it leads to discomfort or pain, this expression is typically brief.5 The performance is ephemeral and thus needs to be captured in images or videos. When ‘double activation’ jewelry is exhibited, the physical piece is usually accompanied by videos and photos of the performance.6 Photography and video art, therefore, have a close relationship with contemporary jewelry art, particularly when the process of ‘double activation’ is involved.13

Lauren Kalman's14, Hard Wear collection15 is a good example of this phenomenon. This collection includes rough, metal jewelry pieces inserted into various body cavities. The act of wearing was filmed and exhibited alongside the physical pieces. Given the rough surfaces and invasive nature of these creations, the viewer can only imagine the discomfort or pain of inserting these pieces.16 This feeling is confirmed by videos of these mini-performances — all performed by Kalman herself to spare others the pain.16 For instance, the video accompanying the Oral Nostril Jewel shows the artist slowly screwing a jagged, amorphous metal piece into her left nostril.7 Even though the frame is limited to Kalman’s mouth and nose, her facial expressions reveal the pain she inflicts on herself. The discomfort she experiences radiates through the video to the viewer, who empathizes with the feeling.

‘Double activation’ and the disruption of body control

‘Double activation’ can profoundly affect our bodies, particularly when we lose control over our own bodily functions. That is also why the body-jewelry entity is ephemeral: we long to get the control back. Fashion theory researcher Linor Goralik13 states that ‘double activation’ jewelry can disrupt our ‘three lines of body control’. According to her, as a child grows, it learns to control bodily functions in three stages. The first stage is the primary control of retaining urine, feces, and body fluids.13 The second stage involves mastering movements and gestures to adapt to various contexts.13 The final ‘line of body control’ is achieved when the growing individual is socialized, learning to regulate facial expressions according to social conventions to either hide or communicate emotions.13 ‘Double activation’ jewelry has the power to take over these three ‘lines of body control,’ whether desired or not.13 Therefore, there is a fundamental difference between the involuntary loss of control and the deliberate surrender of control to a piece of jewelry.

Consider, for instance, Jennifer Crupi’s Ornamental Hands: Figure One and Lauren Kalman’s Oral Nostril Jewel. The former impacts the ‘second line of body control,’ specifically the control of gestures, but this takeover of control is intentional. Crupi aims for the control of the hand to be transferred to her piece of jewelry. The exact effect was calculated. In contrast, Oral Nostril Jewel is entirely about losing control.13 While Kalman could anticipate that inserting this jewelry would cause pain, she could never predict the exact effect on her facial expressions. Thus, the jewelry took control of her emotions and face in an unforeseen manner. Losing control, especially unpredictably, can trigger intense physical and psychological reactions.

‘Double activation’ and materiality

Materiality plays a crucial role in the creation of ‘double activation’ jewelry, shaping how a piece interacts with the body. Artists working in this realm often explore the ‘dark potential’ of traditional materials by subverting their conventional uses.17 Metals, typically polished to a smooth finish, may instead be roughly ground to create friction against the skin or sharpened to pose a subtle threat to the body’s surface — both evident in the work of Kalman. Glenn Adamson17 highlights this dynamic in his essay Metal Against the Body, stating: “Metal can be lovely and useful. … But it is striking how little contemporary jewellery has attended to the less friendly implications of its favourite material. This strikes me as an opportunity missed. … But all jewellery stands, at least potentially, against the body and not just alongside it. … Why have so few chosen to explore this dark potential of body ornament?” While metal is often associated with durability and resistance, textiles—commonly linked to softness and comfort — can also exert control over the body. When tightly wrapped around the skin, fabric can restrict movement, apply pressure, or even cause abrasions.

However, the exploration of materiality in ‘double activation’ jewelry is not solely focused on discomfort or constraint. Sensory engagement extends beyond pain or unease, as demonstrated by Li-Sheng Cheng’s Transform ring (2004). This silver ring features long tufts of red felting wool attached to its interior.18 As the wearer slides the ring onto their finger, the soft wool brushes against the skin in a delicate, almost caressing manner. However, once worn, the felt strands extend outward, forming five distinct ‘spikes’ that project almost horizontally.18 Though the wool remains soft, the hand instinctively adjusts to avoid crushing or distorting the spikes, leading to an altered hand posture and an eventual sense of unease. Here, it is not the material itself that induces discomfort but rather the interplay between design and bodily interaction.

These intentional material choices push jewelry beyond its conventional passive state, actively engaging the wearer’s senses. By understanding the inherent properties of their chosen materials, artists can manipulate them to ‘activate’ the body through jew elry. By leveraging physical properties in unexpected ways, they create pieces that demand attention, disrupt bodily control, and transform the act of wearing into an ephemeral, performative experience.19

1 Jennifer Crupi, Ornamental Hands: Figure One, 2010. Silver, 38,1 x 21,6 x 14 cm. Washington D.C., Smithsonian American Art Museum, inv. 2013.34A-B

2 Crupi has a dual intention with this piece of jewelry. First, she aims to make the wearer and the viewer aware that hand gestures themselves can be considered jewelry. Additionally, this piece materializes the extent to which one is willing to go to achieve elegance and beauty.

3 In this article, ‘double activation’ will not be converted into an adjective. Referring to ‘double activating’ jewelry would imply that the jewelry activates the body twice, which is not the case. The opposite applies to ‘double activated’ jewelry. If this term were used, it would suggest that the body activated the jewelry twice, which is also incorrect..

4 Akiko Shinzato, Chin up, 2018. Brass, size unknown. s.l..

5 It is interesting to consider whether there is a link between ‘double activation’ and ‘body art’. Although the former term relates to applied arts and the latter to visual arts, connections between the two can be found. In both cases, the body is central and, in some instances, may experience pain in the name of art. Additionally, most ‘body art’ performances are temporary and are therefore documented on film.

6 Even when images of ‘double activation’ jewelry appear in catalogs or publications, they are typically images taken during the act of wearing. This approach provides the reader with a clearer understanding of the effect of the jewelry, something that a photograph of the jewelry as an object alone cannot convey.

7 Lauren Kalman, Oral Nostril Jewel, 2006. Gold plated copper, size unknown. s.l.

Jewelry makers can not only shape their creations but also design the interactions between jewelry and its wearer, often resulting in ephemeral mini-performances. Ephemerality, therefore, extends beyond objects' temporality and materiality to encompass the fleeting moments of 'reaching potential.' In the process of 'double activation', a piece of jewelry attains its full potential only at specific instances by forming a unified entity with its wearer. The design elements — form, texture, size, weight, or temperature — ensure that this entity can only be sustained briefly before the wearer finds the interaction unbearable and terminates it. Thus, performativity and ephemerality are more intricately connected than they might initially seem. This perspective reframes ephemerality by focusing on the transient, yet profound, relationships between body and jewelry rather than on the physical lifespan of the pieces themselves. The only way to preserve the interaction between a person and a ‘double activation’ piece is through video or photo, a one-dimensional, deficient eternalization of an ephemeral moment of reached potential.

None.

None.

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

©2025 Taelen. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.