Journal of

eISSN: 2574-8114

Review Article Volume 7 Issue 4

1Professor at the Graduate Program in Communication, Universidade Federal do Ceará – UFC, Brazil

2PhD student of Philosophy at Pontificia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul – PUCRS, Brazil

3Professor and researcher at the Graduate Program in Philosophy at Pontificia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul – PUCRS, Brazil

Correspondence: Parode, Fabio Pezzi, Professor at the Graduate Program in Communication, Universidade Federal do Ceará – UFC, Brazil

Received: July 26, 2021 | Published: August 18, 2021

Citation: Pezzi PF, Maximiliano Z, Oliveira N. Arts, design and culture: in search for sustainability. J Textile Eng Fashion Technol. 2021;7(4):143-148. DOI: 10.15406/jteft.2021.07.00281

Art and design complement each other in the search for quality and sustainability. There are designers who use methods in their practices within the field of art to produce unique meaning for their devices. This is the case of the Brazilian designers, the Campana Brothers. How can art contribute to the design culture of sustainability? How can art enhance consumer culture by design? In conclusion, what can contemporary art currently legitimize? To what extent can aesthetic experience in consumption become one of the ways to build cultural values on the horizon of sustainability? Strategic design, within its theoretical and methodological scope, can provide some answers. Considering sustainability as one of the contemporary paradigms that preaches durability as a value, this paper provides a reflection on the principles of desecration in current Brazilian art and the conceptions that bring art and design together – all through an exploratory approach and according to the methodology of strategic design.

Keywords: design, art, cultural industry, Campana Brothers

Contemporary society faces new challenges in its development perspective. A question like, how will the planet be in fifty, a hundred or two hundred years, is now part of the agenda of many organizations and studies. Climate change, global warming, the greenhouse effect, melting polar ice caps, pollution of rivers, oceans, and air, deforestation and the destruction of countless species of animals are just some of the problems currently being faced. What is the legacy that contemporary society leaves for future generations? Since its global deployment, the model of industrial capitalism has led to major changes in the condition of earthly life. Since the first major oil crisis in the 1970s, sustainability was revealed as the great utopia of the modern world. Oil, as a non-renewable resource, has become, in terms of the future, not a very good strategic choice. Researchers are looking for more advanced technology that could generate energy without damaging the environment (renewable); they are also searching for new consumer behavior in order to prevent the collapse of resources by overproduction. The present study focuses on the production of feelings through artefacts and their relationship with culture in an attempt to relate the intrinsic connection which exists between strategic design projects and the values created by the obtained results. These values can be obtained intrinsically by the materials chosen, by the concepts defined by the built methodologies or by the forms projected. Above all, the intention is to create an explicit logic between art, design and devices that may be associated with the principles of sustainability. These principles were particularly defined by Gro Harlem Brundtland in her report entitled, ‘Our Common Future’. The concept of sustainable development, initially adopted by Gro Harlem Brundtland in the 1980s, became a reference for future studies on development and environment. According to Brundtland, sustainable development is associated with the idea of preserving natural resources for future generations. In the report, ‘Our Common Future’, she says, "Believe in sustainable development, which implies meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs".1

Particularly in the field of strategic design, our interest is to investigate the possibility of design as a strategy for changing the world. An attempt at identifying, within the set of contemporary productions, the existence of design products that encourage a culture of sustainability has been made. Interest lies particularly in the field of design, from the point of view of its practices and methodologies which could be convergent with this perspective. In order to carry this out, we base ourselves on a qualitative research perspective, whose foundation is in the order of signification, semiology, and cultural studies, based on sign-laden approaches, oppositions or similar vectors of meaning. As a whole, from the methodological practices of strategic design that include the analysis of language in syntax-related hermeneutic principles of interpretation, we seek to raise hypotheses and argue around the construction of design as a cultural device close to art, capable of generating projects based on common well-being and the preservation of the environment.

The common future, as is emphasized by the report submitted by Gro Harlem Brundtland, is the key concept, and it appears that this notion is associated with the production of new conditions of existence on the planet; Thus it directs our focus towards cultural production that could be related with the notion of sustainability through design. It involves researching for devices that by their nominal value would be generating new concepts and perceptions. Can the work of the designers, the Campana Brothers, be close to the purpose identified as sustainable development? An attempt will be made to identify in the work of these designers elements that operate towards a culture for sustainability, postulating the order of difference, uniqueness and their ‘being’ as regulative principles of ‘campanianos’ devices. The argument to be developed here covers the production of meaning through the devices. Why should certain Campana appliances, such as a chair, a lamp, a closet, etc., be closer to certain values of the field of sustainability than others? It is considered, however, that in some cases the role of the method is more important than the choices that led to the construction of a particular concept and the resulting appliance itself.

The belief is held that combining art and design, to work on the threshold of one and another, is part of a methodological choice. Thus, the Campana brothers have a purpose made explicit with their choice of bringing art closer to design: the generation of symbolic values through the brand name of the subject. Their work always refers to the subject of creation, the author. This perspective is contrary to the hegemonic model based on seriality and universality. Their work claims the singular and the particular. According to Adorno, a work of art resists social mass processing; it is a part of its immanence, differences in production, singularities. He says: "the immanence of society in social work is the essential relationship of art, not the immanence of work in society. Because the social content of art is not established outside their “principium individuationis” but is inherent to individuation, art is itself a social element".2 The artistic movements of the nineteenth century were, in general, movements which fought against all transendance of beautiful form from ‘savoire-faire’ and the tenets of the academia about making art. Of the imprsssionists of the salon of Rejects of 1863, the most prestigious works of modernity, the aesthetic movements of that period, particularly though Dadaists, formulated pereptual values within the social fabric which mainly looked for the distance between idealized form and the emperical experience of art. According to Adorno, “modern art is that which, in accordance with its way of experience and as a result of the crisis of the experience, absorbs what industrialization has produced under the dominant relations of production”.2 The various aesthetic ruptures produced by the vanguards of the twentirth century led to an accelerated crisis in the field of art. The paradigm of art was becoming closer and closer to a world ruled by aesthetic conventions intrinsic to individual acceleration. Ephemerality, repetition, performativity, fragmentation, hybridity and simplification are just some of the aesthetic features of this process. As Jimenez says, "the constantly disappointed hope of seeing a reconciled society being established in the name of this 'ideal of humanity' expressed by the formal upheavals of the beginning of the century, illustrates well that art is denied its role of positive or negative mediator between an ever-increasing rationality of social totality and the sensitivity of the individual" (JIMENEZ, 1995, p. 31).

For Arthur Danto3 aesthetic movements of the twentieth century brought art to the extreme of banality, of mere convention. According to him “the difference that separates art from reality, depends solely on the convention, in the sense that every object they identify as a work of art becomes a work of art."3 In any case, whether from the experiences of Marcel Duchamp or Andy Warhol, the field of art diluted its borders, simulating its transgressive states, becoming more accustomed to the logic of the commodity and the insidious model of market relations. As already observed by Walter Benjamin,4 technical reproducibility in modernity transformed the aesthetic experience. Now stripped of its aura, art aestheticized itself with the projects of entertainment and consumption. This would be an expression of art without autonomy, an art shaped by market values. Adorno reiterates this position by strengthening the critique of art in the context of the cultural industry. According to the philosopher, "art is not only social through its form of production, which focuses on the dialectic of productive forces and relations of production, neither through the social origin of its thematic content. It becomes social by adopting an antagonistic position towards society and only occupies such a position as autonomous art ".2

However, engagement with the art market, as negative as it may seem, has approached design. It is likely that the movement known as the sixties Pop Art was the fore-runner of the explanation of this relationship. This aesthetic movement, inaugural in the art field, was characterized by a certain detachment from political and social issues.

However, as Bernard Stiegler says in his book “De la misère symbolique” the political issue is an aesthetic issue and vice versa : the aesthetic issue is a political issue. (...) The abandonment of political thought in the art world is a disaster" (STIEGLER, 2004, pp. 17-18). Conversely, it can be said that in the field of design, such as with the works of the Campana brothers, the simple fact of bringing together art and design, creating a hegemonic aesthetic opposite, incidentally, an aesthetic that emphasizes the importance of originality and induces new sensations and reflections, already represents political recovery in the works.

In this case, it can be said that the work, by its uniqueness and difference within a mass context, produces resistance, opening up other viewpoints and experiments. The work in this case invites a contradictory experience, generating new perceptions of the world and culture. It is in this sense that the work can generate innovations in the field of meaning, bringing to the social field new possibilities for interactions either with objects themselves or between animate beings. The works that appeal to the field of art with their own value is works that break with the pattern of production and consumption, guided by the logic of planned obsolescence, because they are works that appeal to feelings and affections. The object of design with a style of art is an object that attracts a particular type of assessment and differential symbolic value because it removes itself from banality, putting itself above the commonplace and, therefore, is treated as something special that tends to be long-lasting.

To answer the question, what art and contemporary design are currently legitimizing, the essay "The Art world", published in 1964 in the American journal "The Journal of Philosophy, should be remembered, where the professor emeritus of philosophy at Columbia University, Arthur C. Danto, begins desclosing that Socrates: "spoke of art as a mirror prefixed to nature [...] Socrates view mirrors as that which reflects what we already see. Thus art, in that it is like the mirror, provides little accurate duplication of the appearances of things and does not provide any cognitive benefit" (DANTO, 2006, p.13).

For the author, the result of the previous discussion is weak because, to refute a theory, it would be expected for Socrates to use a "counter example", like the example of the mirror, to classify it as being "imitation is not a sufficient condition to 'be art'" (DANTO, 2006, p.13). For Danto, this theory fails; it would only become evident with the invention of photography.

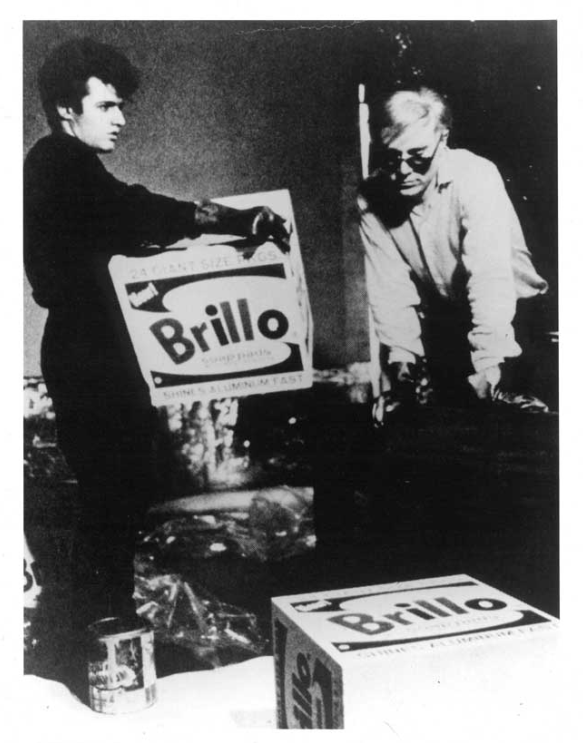

Differentiating works of art of mere objects is not an easy task. How does one distinguish a common Brillo box from a consecrated work of Andy Warhol? Danto says,

"What, after all, the difference is between a box of Brillo and a consistent work of art of a Brillo box is a certain theory of art. It is the theory that is received in the art world and prevents the object from falling into the condition of ‘a real object’, (in the sense that it is different from artistic identification [...] which is the role of artistic theories, today as always, to make the art world and art itself possible " (DANTO, 2006, p.22 ).

To reach the status of "Work of Art", theory of art would not be able to cope with the transfiguration of an object without the support of fashion ; in this sense Pop Art found an ally. Danto says "fashion, as happens, favors certain lines of stylistic matrix: museums, connoisseurs and others are strong factors in the art world [...] one line in the array is as legitimate as another [...] an artistic achievement is, I suppose, the possibility of adding a pillar to the matrix" (DANTO, 2006 p.24). Does Danto mean that the transfiguration occurs from the moment in which the institutions of the art world give the status ‘artwork’ to an object or appliance? (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Gerard Malanga and Andy Warhol preparing to silkscreen a Brillo Box at the Factory,1964.

Source: http://www.i-italy.org/10337/mysterious-case-315-johns (accessed on 30/06/2021)

By linking the relevant aspects of the relationship between the world of art with fashion, Lars Svendsen, in the book Fashion a philosophy, begins with a reflection of the more striking events, in a chronological way, within a social and political perspective since the beginning of the twentieth century, to conclude: "during the twentieth century, art and fashion are like neighbors; they either like each other or they can’t stand each other".5

Based on these affirmations, a wider understanding of the complex social phenomena of the relationships and representations in the world of art appears, which can later establish an approach with the concept of Pierre Bourdieu’s symbolic value, to finally reflect on the processes of legitimization within contemporary parameters.

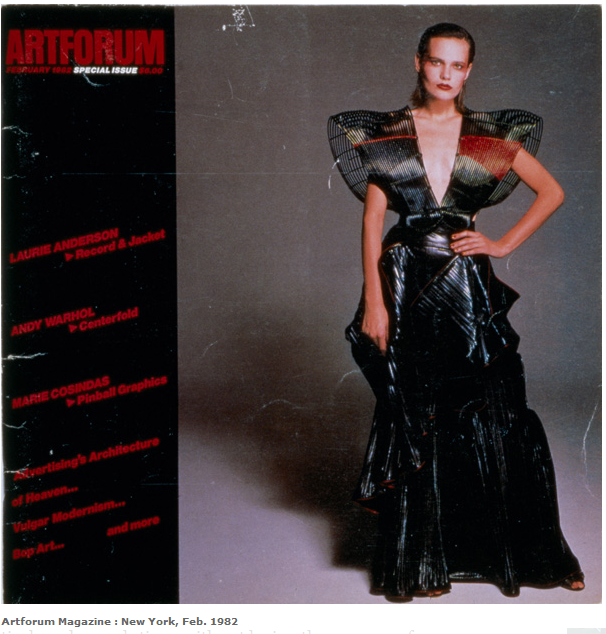

For Svendsen, the key moment of "mutual rapprochement between fashion and art occurred in February 1982 when the cover of the influential American magazine Artforum showed a fashion model wearing an evening gown designed by Issey Miyake" (Figure 2).5

Figure 2 Cover of the magazine Artforum, Feb. 1982.

Source: https://www.artforum.com/print/archive/20/31716 accessed on 30/06/2021.

According to Svendsen, from this rapprochement other influential magazines in society, or in other words, tools of symbolic production and generation of values, followed the same path with the critics approval while designers began to publish more in fashion magazines. For him, "the most 'artistic' aspect of fashion is typically associated with its exhibition".5

Symbolic power, according to Bourdieu, "is a power for constructing reality that tends to establish [...] the immediate sense of the world (and in particular the social world)".6 For the production of beliefs, according to the author, there must be a structural and hierarchical relationship between those who "wield power and those who are subordinated".6

It can be said that the most influential art critique magazines play their role as opinion formers within the realm of the art world, defining and setting parameters of value. However, the art of the twentieth century and that of the current one is always reinventing itself, constantly presenting us with new elements to be discussed. Svendsen relates: "In the opinion of the art theorist Clement Greenberg, it is part of the essence of modernism that every kind of art should prove its own identity, like a hallmark of its absolute autonomy".5

Once the "work of art" is built, it shall possess "symbolic value". To make a brief illustration of the "transfiguration" process, the question has been aired, ‘what are the effects of modern art in our society?’ Modern art, design, and sustainability relate with each other to deal with a production of collective meaning and so, what is the cultural production in relation to future generations?

The political will or desire of the Campana brothers is evident in producing art that makes it possible to create meaning ; values involving sustainability and respect for what is outside the hegemonic standard; the preservation of traditions and old techniques are also part of a proactive attitude towards culture. The method of the Campana brothers reveals itself to be against the method, opening it to criticism and reflection. It can be considered that there is a relationship of implication and relevance between the Campana brothers and those who produce their works, as though among the producers there were powerful groups willing to deal with a ‘massification’ process of society and at the same time, environmental corrosion. At a future date, it would be necessary to make a wider semiotic, placing the Campana brothers in a larger system, where they would cease to be producers and would become instead the product. This order of questioning is proposed by Bourdieu in The Rules of Art by the question: who is the producer of the producer ?.7

The focus of this research is the work of the Brazilian designers, the Campana Brothers. The works of these designers raise some important points to think about concerning the relationship between art and design, and beyond that, more elements that can help us in thinking about culture and sustainability elements. The Brazilian designers have had an unorthodox career, Humberto and Fernando Campana are not designers by profession but a lawyer and an architect, respectively. They left a peripheral country, in this case, Brazil, and won international fame, becoming today an undisputed reference in contemporary design. No doubt Italian design exerted and exerts strong influence on the Brazilian designers to the point that many of their projects are recognized as being made in Italy. The Italian company, Edra is responsible for most of the production of the Campanas ; however, the dynamic creativity of these designers refers to Brazilian culture. The ‘Brazilianness’ motto is inspiring and largely ends up defining the concepts involved in the projects. The chair, entitled ‘Favela’ is a great example of this rhetoric. The Campana’s method is experimental and is subject to chance.

For both the Favela chair or the Red chair, a research into the underlying meanings of these objects would probably take us to the notion of improvisation and ephemerality. There is successful improvisation in relation to the composition of the materials and by the significant value given to the juxtaposed units of small pieces of wood in an arrangement that, by analogy, resembles the structure of a favela, as well as the tangled wires that find a particular order in the apparent chaos of the threads. Here we have the game of appearances in ways that recall the sensations of pleasure and displeasure, between comfort and discomfort, between chaos and order. Over the years, the Campana brothers have developed a unique style, with a unique repertoire where materials, shapes and language produce texts through design objects. What do the Campana want to say between design and art?

Through reports from the designers as well as through the significance of the objects, we know that Brazilian culture and identity have been highlighted through campanianos’ objects. Miscegenation of Brazilians, the size of the Amazon rainforest, the wealth of fauna and flora as well as the extremes of social conditions faced by the country, produce a unique type of culture, a hybrid culture, strongly influenced by popular folklore, where mystical and religious syncretism appear. There is, however, a disguised violence, which sometimes erupts on the streets, in social movements and also in art and especially in film. This is the case in a series of films such as ‘Pixote’, ‘The law of the weakest’ (by Héctor Babenco, 1981), ‘City of God’ (by Fernando Meireles, 2002) and ‘Elite Squad’ (by José Padilha, 2007). Violence in Brazil is the result of a disruptive social condition impacted by a strong concentration of wealth in a few. Paradoxically, this gap between wealth and poverty, between privilege and insecurity, is transmuted by the culture of carnival, football and religious festivals. Brazil is a country of continental dimensions, full of contrasts and an exuberant nature. These features appear in the work of the Campana brothers; in other words, the designers try to significantly imply Brazilian culture and nature in their objects. Take the case of Boa’s couch that suggests a snake (Figure 3) (Figure 4).

Figure 3 Boa Sofa, 2002.

Source: http://decojournal.com/boa-sofa-by-fernando-and-humberto-campana/ accessed on 30/06/2021.

Figure 4 Sucuri of the Amazon.

Source: http://www.infoescola.com/repteis/sucuri/ accessed on 30/06/2021.

This relationship with nature and that which is random makes each design object of the Campana hold a unique and particular dimension. In art, even in repetitive processes, there is always a space for uniqueness, for what is different. These characteristics do not only happen in the field of art but also in craftwork. The works of the Campana are located on the border between art, craft and design. Perhaps the Campana, with respect to the repertoire of art, are situated between Art Povera and Pop Art, despite being contrary aesthetic movements, because, while the former suggests a return to simplicity and nature, the latter brings art and consumption together and the world of kitsch objects. It is precisely this plural, multi-and trans-disciplinary way that makes the Campana’s works so exciting (Figure 5).

Figure 5 Favela Armchair, 1991.

Source: http://novitaambientes.wordpress.com/2009/11/11/cadeira-do-mes-favela/ accessed on 30/06/2021.

It is likely that in the case of these designers the pursuit of originality and authorial trait are some of the factors that bring their work nearest to an expression of art. The Campana Brothers’ work is not done on a large scale and each piece, due to it’s almost hand made method of production, presents inevitable differences one from another (Figure 6).

Figure 6 Red Chair, 1993.

Source: https://www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning/fernando-campana-and-humberto-campana-vermelha-chair-1993/ accessed on 30/06/2021.

It is through the features of a semiotic analysis and figures of speech, being analogies or metaphors, that the works of these designers acquire contours that allow us to think of a philosophy of design.

The Campanian baroque

The concept of Baroque design of the Campana entices us to reflect on contemporary culture and the intrinsic value of new consumer behavior . The curves and sinuous lines as well as the folds and shadows that appear in the Campana’s work, even in the 90s, were a reflection of a predisposition to the principles of the Baroque. According to Deleuze,

"Baroque refers not to an essence but mainly to an operative function, to a trait. It never stops making folds. It did not invent that: There are all the folds coming from the East, Greek, Roman, Romanesque, Gothic, Classic ... but it curves and re-curves folds, leading them to infinity, fold over fold, each fold with another fold. The trait of the baroque is the fold that goes to infinity. ".8

In 2013, the Campana brothers held an exhibition at David Gill Galleries in London entitled, Brazilian Baroque. That exhibition consisted of pieces inspired by the Brazilian Baroque of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The pieces had already been exhibited in the Museum of Decorative Arts in Paris in the same year. Pieces that from a distance seem to be just one thing only, like a sofa, a lamp, a table, etc. However, "when viewed up close, the details amaze. There are keys, leaves, cupids and crocodiles carved there". Materials which replicate, bend, fuse, creating an image that plays with the forms of the Baroque, producing bowel, curves, volumes that stimulate the imagination and touch. The guiding principle of the work is the transfiguration of the commonplace material into luxury, the re-use and redefinition of materials impoverished by the passing of time and use into desired, prized and luxurious materials (Figure 7).

Figure 7 Torquinio sofa, Fernando and Humberto Campana, 2012.

Source: https://www.designboom.com/design/campana-brothers-barocco-rococo/ accessed, on 30/06/2021.

Baudrillard has been one of the most exciting sociological references regarding reflections on the consumer society. According to him, the man of a consumer society, also recognized as homo economicus, is a being who is constantly in search of pleasure, happiness; his attitude towards life is hedonistic and individualistic. However, the need of the consumer society is that happiness is measurable. This is measured through ostentatious objects. Objects are no longer consumed by their value in terms of use but by their symbolic value. This is a fetishistic logic where what matters most is the symbolic value of the object, what it stands for and means in a particular context. It would be the case when considering the symbolic value of campanianos objects, not just for what they mean in terms of culture, but particularly their sociological aspect. What would it mean in terms of sociology to own an object like the sofa below (Anhanguera Sofa), the sale value of which is $ 193,000? (Figure 8).

Figure 8 Sofá Anhanguera, Fernando and Humberto Campana, 2012.

Source: https://hometone.org/4299/2012/10/06/the-193000-mongolian-lamb-sofa-by-campana-brothers/ accessed on 30/06/2021.

There is no need to go far in this discussion; it is sufficient to note that this object is reserved for a limited number of clients who seek to distinguish themselves socially through ostentation and luxury. Perhaps this is the greatest paradox of the Campana’s production: cheap materials, expensive objects. Looking beyond a sociological critique, it can be considered that the objects produced in this perspective bear within themselves a mark of rarity and, therefore, of social distinction for those who possess them. According to Baudrillard, "consumer society, as a whole, results from the compromise between egalitarian democratic principles, (...) and the fundamental imperative of maintaining an order of privilege and domination".1 According to Baudrillard, consumer society reaffirms the logic of unequal distribution of wealth, creating on one side abundance for a few and material instability for many on the other; it is the structural poverty of the system and the maintenance of privileges for a few.

Foucault’s theses on disputes and power struggles appear more than evident in the context of contemporary design, which the Campana brothers are part of. In a possible genealogy of the Campana’s work, a discourse can be envisaged which is constructed by erratic, inside out, impertinence of art. It would be an address in a minor field, which speaks of the difference. To analyze the work of the Campana, as Foucault says, apropos of a genealogy, "is to mobilise local, discontinuous, disqualified and unlegitimized knowledge against a unitary theoretical dimension, which seeks to purify it, organizing it hierarchically, sorting it into truly known names on behalf of the rights of a science, which are witheld by some".9 It is perceived on the one hand that the hegemonic model, produced on mass and unquestioningly by big industries, seeks to operationalize practical, cheap and easily disposable models. On the other hand, There is the design of the maker, in which the Campana designers are included. This design requires the effort of creativity; the work is sealed by the artist's impression, giving value to the man, not the machine and, consequently to culture. The work of the Campana’s is included in this epistemic aspect, where culture and sustainability fit well in a selection of offers, occasionally bizarre for some, sometimes exuberant because of the vivid colors, the exotic shapes but ultimately thought-provoking for open research.

The analysis of the Campana Brothers' work in relation to the field of art allowed us to build a theoretical-critical framework of the industrial production and consumption process, considering its environmental and social impacts, highlighting the field of design in particular, symbolic possibilities of adding value, allowing for the potential of projects to be qualified in their human and environmental relationship. This would be the main justification and result of this study, namely, qualifying the design project through critical and well-founded reflection, expanding the creative spectrum of the method beyond functionalist practices. That being said, we conclude that form no longer blindly follows function, but form perspectively follows critical reflection and based on the common future of humanity and the planet.

Finally, it can be concluded that a discussion of differences is arrayed around these works that speak louder than was intended because they incite the imagination and open up possibilities for originality to occur, originality of the act, of the experience and thought. The work of the Campana may subscribe to the second species of organization, as formulated by Deleuze and Guattari in A Thousand Plateaus. According to the philosopher, the second species of organization is characterized as being "molecular and of a 'rhizome' type. The diagonal is released, breaks or becomes snake like. The line does not have boundaries and passes between things, between points. (...) Multiplicities of ‘becoming’ or transformations which are no longer countable elements and ordered relations; vague arrangements and no longer precise, etc.".10 Taken as a source of inspiration for culture and nature, the work of these designers continues in a process of ‘becoming’ because it carries the infinite in its genesis.

None.

None.

The authors have no conflict of interest regarding this paper.

©2021 Pezzi, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.