Journal of

eISSN: 2574-8114

Review Article Volume 11 Issue 1

1Fashion at the Creative School, Toronto Metropolitan University, Canada

2Faculty of Industrial Design Engineering, Delft University of Technology, The Netherlands

Correspondence: Danielle Martin, PhD, Fashion at the Creative School, Toronto Metropolitan University, 350 Victoria Street, Toronto, ON, M5B 2K3, Canada, Tel 416 979-5000 ext. 554697

Received: January 30, 2025 | Published: February 21, 2025

Citation: Martin D, Hoftijzer JW. A “fashion design for DIY” poiesis: enabling DIY to support awareness and responsible consumption. J Textile Eng Fashion Technol. 2025;11(1):48-57. DOI: 10.15406/jteft.2025.11.00403

Do-It-Yourself (DIY) product design offers an alternative approach to traditional top-down industrial product design practices and promises to support reviving consumer awareness and appreciation of how things are made.

Similar to the consumer product industry, ready-to-wear fashion is facing the hegemonic trend of neomania – an obsession for novelty that causes serious overconsumption issues. Even more in the last three decades, there is an enormous accumulation of fabric and garment waste sent to landfills each year. A change should come from questioning traditional design processes to alter the distant relationship between people and the clothes they purchase.

“Design for DIY” (DfDIY) projects run by fashion design students enabled amateurs to participate and express their creativity. The “research-through-design” experiments were aligned to the generic “DfDIY framework”. The projects were conducted to develop knowledge concerning the FDfDIY poiesis of facilitation and design.

By positioning facilitation as a key element of the DIY experience, this study advances existing knowledge by expanding beyond previous research that has explored DIY in sustainability,1,2 entrepreneurship,5 and open design.3 Unlike past studies that primarily examine DIY as an autonomous or countercultural practice, FDfDIY introduces a structured, guided approach that bridges gaps in skill and feasibility, enhancing accessibility for amateur participants. Additionally, this study integrates both digital and manual methodologies, distinguishing it from prior work on digital DIY4 by demonstrating a hybrid approach to garment customization.

By emphasizing facilitation, this study expands on DIY research in sustainability,1,2 entrepreneurship,5 and open design.3 Unlike studies framing DIY as autonomous or countercultural, FDfDIY offers a structured approach that enhances accessibility. It also integrates digital and manual methods, setting it apart from digital DIY studies4 with a hybrid garment customization model.

This paper describes the experiment setup and the development of FDfDIY strategies using student surveys and amateur questionnaires. The findings from these experiments have practical implications for those interested in this concept and the process of facilitating DIY in the field of fashion design, as well as for entrepreneurs seeking to implement a new FDfDIY business model.

Keywords: product, fashion design, DIY, awareness, neomania

Accession of fashion design mass production

The industrialization of fashion in the 19th century marked a turning point in garment production, shifting from handcrafted techniques to large-scale, mechanized manufacturing. The introduction of the inch-marked tape measure (c.1820) enabled greater standardization, while the industrial sewing machine, emerging in the early 1850s, revolutionized factory production by accelerating output and reducing reliance on manual craftsmanship.6 More than just technological advancements, this shift reflected a broader transition to repetitive, mechanized labor, where efficiency and mass production took precedence over artisanal skill (Mantoux, 1906, p.179-181).

Since then, ready-to-wear has been driven by speculative manufacturing, producing standardized garments at reduced costs, often framed as the democratization of fashion.7 However, the contemporary fashion system operates at an unprecedented pace, with new designs released not just seasonally but daily. Fast-fashion companies like Shein exemplify this acceleration, boasting: « 1,000+ new items launch every day New Clothing Arrivals Create Your Own Style. ».8 While this mass production model has made fashion more accessible, it raises pressing concerns about its broader social and environmental implication, While this mass production model has made fashion more accessible, it raises pressing concerns about its broader social and environmental implications; at what cost?

Parallels with industrial product design

The mass production model of the fashion industry shares notable similarities with the field of industrial product design. As the term suggests, industrial product design focuses on the large-scale manufacturing of consumer goods and products. This approach is fundamentally rooted in mass production, mass distribution, and the culture of mass consumption. The priority often lies in maximizing sales rather than responding to individual consumer needs, creating what Marlini9 describes as a market-push scenario.

Both the fashion and consumer goods industries rely on speculative mass production, optimizing efficiency and cost reduction for global distribution. This system has profoundly altered the role of the consumer, reducing them to passive recipients of goods. Consequently, amateur knowledge, handcraft skills, and consumer awareness have significantly declined.

Problems caused by unawareness

The contemporary state of both the ready-to-wear fashion industry (ready-to-wear) and industrial product design, can, for several reasons, be regarded as troublesome. Characterized by the division of labour, large-scale manufacturing, and management of a perpetual change, the industrial system has led to a widening gap between production and consumption. This disconnection between production and consumption has resulted in a widespread situation of “unsustainability” (see section “Unsustainability”).

Modern industrialized societies have fostered extensive and harmful expanding consumption behaviours. Rather than investing effort into making or mending, consumers have become increasingly accustomed, even addicted, to purchasing new “stuff”, worsening their awareness of where things come from and how things have been made.

Erosion of appreciation

Beyond the disconnectedness from production discussed in section “A new approach: Do-It-Yourself (DIY)”, another challenge plagues the fashion industry: people are no longer willing to pay for the quality of garments created in ethical conditions. There is a growing lack of awareness surrounding the intrinsic value of fabric and garments (Lee, 2020), including their origins, transportation, the conditions in which they were manufactured, and the environmental impact of the fibres used in their production. This erosion of appreciation is due to the distance between manufacturing and the user, which has been growing since its origins, dating back to the split caused by the Industrial Revolution.10 Due to a declining appreciation for refined skills and the diminishing recognition of the sewer’s work, fewer young professionals are choosing to enter the field. As discussed at the Forum Main-D’oeuvre mmode in Montreal (November 16, 2018), this decline raises concerns about the future transmission of traditional knowledge in garment-making.

Unsustainable fashion

Awakening of the environmental impact

Around 2006-2008, concerns about unsustainable practices in the fashion industry began to surface. Rumours circulated about American and Canadian brands disposing of overproduced garments, whether unsatisfactory or unsold, by burying or discreetly discarding them in landfills.

However, it was not until 2018 that the issue gained widespread attention when Dara Prant (July 26, 2018) exposed overproduction figures of the publicly traded company Burberry on one of the fashion industry’s regularly consulted websites, Fashionista.com. A few days later, the general news platform BBC broadened the matter to a wider audience with its article "Fast Fashion: Inside the Fight to End the Silence on Waste".11 While eco-responsible fashion had been recognized in academic research since 2009,12 the general public only became significantly aware of these issues post-2018. In 2021, on the sidelines of the UN Climate Change Conference in Glasgow (COP26), a report shocked the general public: “The fashion industry is the fourth most polluting on the planet, just after the energy, transport and agri-food sectors. It alone produces 10% of all carbon emissions. Textile dyeing is the second largest source of water pollution in the world.”13

Neomania and overproduction

Sociologist Colin Campbell argues that “the love of novelty played a central role in the Industrial Revolution.” The concept of “neomania”, or obsession with novelty,14,15 has transformed the process of design and driven fashion’s accelerated frantic cycles. Testing disaster in universities is a challenge that Virilio16 threw at us. However, rather than being addressed in academic discourse, this intervention has been fully embraced by the fashion industry.17 As noted by Oakdene Hollins,18 the issue of overconsumption dates back to the beginning of the Industrial Revolution but has escalated dramatically in apparel sales in recent decades.18

Neomania fuels both overconsumption and overproduction of textiles and clothing, which have become critical issues in the field of fashion over the past two decade (http://www.cirfs.org/KeyStatistics/WorldManMadeFibresProduction.aspx)1. The environmental consequences are severe: according to the GFA report cited by the BBC, an estimated 92 million tonnes of textile waste are discarded annually, with projections indicating 134 million tonnes by 2030 (GFA, as cited by Beall,19). When textiles enter landfills, they persist for decades, emitting methane gas, a strong contributor to climate change.20

Textile fibers

Cotton remains one of the most widely used natural fibres in the apparel industry, covering over 70% of the market for men’s and boys’ clothing in the United States. (https://www.cotton.org/pubs/cottoncounts/fieldtofabric/uses.cfm). However, its environmental impact is alarming.

Weltrowski, Dion, and Julien21 highlight that cotton cultivation relies heavily on fertilizers and chemical pesticides, consuming 11% of the world’s pesticides and 25% of insecticides.21

Even the so-called organic cotton poses environmental concerns due to its excessive water consumption for its cultivation and finishing process, contributing to one of the worst ecological disasters produced by humans. Thus, since the end of the 1980s, the cultivation of cotton, which necessitated the irrigation of two rivers, has almost drained the entirety of the Aral Sea.21,22

The issue of planned obsolescence

Industrial mass production necessitates significant investments in tools, molds, and inventory, often leading to deliberate overproduction. Planned obsolescence, a commercial strategy aimed at shortening product lifespans to stimulate sales, is deeply embedded in the fashion industry, where an endless cycle of renewed trends ensures constant consumption. As Prasad Boradkar23 observes, "en vogue" manufacturers and designers continually promote innovation under the guise of economic progress.

The role of fashion design education

The alarming statistics of the fashion industry have been taught in fashion schools for a few years now. We operate in a field that pollutes, exploits labour, and depletes natural resources. In addition to acquiring knowledge and developing skills for a field they are not yet familiar with, our students are challenged to rethink this field in the face of its increasingly catastrophic consequences.24 This accelerating disaster shapes actual teaching practices, but how can we convey this sense of urgency to aspirant designers?

A new approach: Do-It-Yourself (DIY)

For those reasons, a true solution cannot come from small, superficial changes that maintain existing people’s behaviours and the system we live in. Instead, change must come from questioning and altering the distant relationship between people and the things they use and need. People’s awareness of how things are made and where things come from must be restored:

This proposal advocates for a shift towards a Do-It-Yourself approach. In other words, it aligns with Toffler’s concept of “sector A”,28 where individuals engage in self-production, merging the roles of producer and consumer in one person.29 The DIY concept empowers laymen to develop skills, strengthen connections, and gain awareness of the effort required to manufacture the things they use. As Bonvoisin, Galla & Prendeville30 describe, Do-It-Yourself (DIY) is a “method of building, modifying, or repairing things without the direct aid of experts or professionals.”

Learnings from “DIY product design”

In product design and architecture, the concept of Do-It-Yourself (DIY) design, also referred to as amateur product design, has gained significant attention in recent decades. This approach is closely linked to theories of attachment,31,32 involvement, and “Being” (self-sufficiency, enabling the expression of creativity, and participation),27 as well as DIY’s role as a counterpoint to consumer society.33 Notable examples include platforms such as Shapeways, Quirky, Instructables. Early scholarly discussions of DIY design include Bas van Abel’s “Open Design Now”34 and Ellen Lupton’s “Design it Yourself”, which focuses on graphic design.35 Additional studies reinforcing the relevance of DIY in design include works from Wolf & McQuitty36 and Atkinson.37

A more recent series of Design for DIY (Design for Do-It-Yourself) studies within the field of product design38 has led to the development of a generic Design for DIY framework (Figure 1).

This framework includes a sequence of design cycles. Each of these design cycles describes a typical design process from initial concept to finalization. It serves as a foundational reference for aspirant designers engaged in Design for DIY projects.

Subsequently, the present study discusses an experimental approach that explores “Fashion Design for Do-It-Yourself.” Fashion design students were challenged to develop both a design concept and process that would include options for the amateur to interfere in the design of the garment before its final realization.

Goal

Through research-by-design, knowledge was developed on the poietic aspects of facilitation and design within Fashion Design for DIY (FDfDIY). Students, referred to as aspirant designers, had considerable freedom in defining their Design-for-DIY project. However, the primary objective was to ensure that the amateur’s DIY activity fostered an awareness of the making process, specifically of cutting and sewing.

The aspirant designers were tasked with developing a well-structured interaction process, striking an ideal balance between simplicity and a gratifying challenge for the amateur. Their role was to act as facilitators and enable interaction from the amateur. Each aspirant designer was required to design a mini collection of three garments or accessories and determine the parameters for the FDfDIY project (see section “Brief description of the assignment and demographic context”).

A key requirement was to find the right balance between the simplicity of execution and the sense of pride of the amateur, ensuring engagement through aesthetic and/or functional contributions to the design of the garment or accessory.

Research questions

Brief description of the assignment and demographic context

The study was conducted in a first-year Fashion Design B.A. class at a university in a large Canadian city. The class consisted of seventeen students, primarily aged 19 to 22, with one mature student aged 35. The group included thirteen female and four male students. In terms of cultural background, twelve were French-Canadian, three were French, one was Spanish, and one was a second-generation Mexican-Canadian.

The FDfDIY project was a five-week assignment in which the aspirant designers first had to define the type of interaction, making it the initial question to consider and the first step to be determined. After having presented various examples, the interaction could be categorized as follows:

Over two weeks, the students were asked to develop a preliminary interaction process to be reviewed and confirmed with the instructor. During this stage, one-on-one discussions focused on how the project could achieve an optimal balance between simplicity and a gratifying challenge for the amateur. Their concept was documented in a research sketchbook where they compiled their observations, inspirations, photos, sketches, graphics, reflections, and work-in-progress ideas. Additionally, they were required to develop a preliminary questionnaire to gather insights from the amateurs testing the FDfDIY project. Students also had to discuss their observations and conduct a self-evaluation of their work at this stage.

At the end of the five-week project, students presented their FDfDIY mini collection, incorporating a unique type of intervention across three different garments or accessories. Prior to this, they had tested their FDfDIY process with three amateurs, gathering live feedback through both direct participation and the questionnaire. Their final presentation, supported by a visual component, showcased their project to the class, highlighting amateur participation and presenting results through technical sketches and/or fashion illustrations.

Student surveys

To assess the projects from both the instructor’s and the aspirant designers’ perspectives, students were asked to fill out a questionnaire reflecting on their experience with the FDfDIY process. The survey explored their perceived differences between FDfDIY and traditional fashion design projects, the advantages they observed, the actions they took to anticipate challenges, and their overall experience. The responses provided by the aspirant designers were used to thoroughly evaluate the projects, as discussed in the section “Findings and conclusions.”

The survey included the following questions:

Amateur questionnaires in FDfDIY experiments

As part of the FDfDIY project, students were required to design and administer a questionnaire in order to document the amateur’s experience. While the questionnaires varied slightly between projects, they all included three core questions:

A selection of project outcomes

Each project includes a tested process, a resulting product (or series) designed for manipulation, and a DIY platform or template provided to the amateur. Out of the original 17 cases, six were selected for further investigation based on their clarity, representativeness, and perceived potential commercial viability from the researchers’ perspective. The selection also considered diversity in two key aspects:

While the cultural diversity within the group was somewhat limited, effort was made to ensure the broadest possible representation of perspectives and approaches within the available demographic.

The aspirant designers’ projects resulted in a diverse range of outcomes, with regard to various design decisions made, steps taken, processes followed, and conclusions drawn. This section presents the results and processes of three projects, both textually and visually. The conclusive findings from the surveys will be discussed in the following section, “Findings and conclusions.”

“LA TRANSPARENCE” (Description of case A (project 2))

With the guidance of a professional, the amateur is invited to costomize a fitted little black dress (LBD) by adding transparency. The dress is available in four sizes, and the body can be revealed in three different predetermined ways:

To facilitate this customization process, the aspirant designer developed a digital platform using Adobe Illustrator. This platform enables real-time interaction with the consumer, displaying both the technical sketch and fashion illustration of the LBD. The selected alterable horizontal or vertical lines are visually linked, providing an instant preview of the modified design (Figure 2).

As discussed in the next section (section “Finding and conclusions”), the platform and intervention provided to the amateur in this project proved to be more challenging than the aspirant designer had anticipate, particularly due to the use of see-through fabric that revealed the skin’s surface, as illustrated in Figure 3. Additionally, the neckline and hem posed further technical challenges in the garment’s construction.

“WAVE” (Description of case B (project 6))

The amateur is invited to alter a unisex basic garment (a double-layer t-shirt, a poplin shirt, or a hoodie sweatshirt) by stretching or displacing the all-over wave print, which simultaneously modifies the garment’s hem.

To facilitate this process, the aspirant designer created an instructional leaflet and an Adobe Illustrator platform, guiding the amateur through the step-by-step intervention of altering the wave print and hem shape. The amateur could modify the design directly within the platform (Figure 4) (Figure 5).

Although the amateurs were not familiar with Illustrator software, they could however participate comfortably with the help of sufficient guidance. Participants were even satisfied with their results. More details and conclusions are revealed in the next section (“Findings and conclusions”).

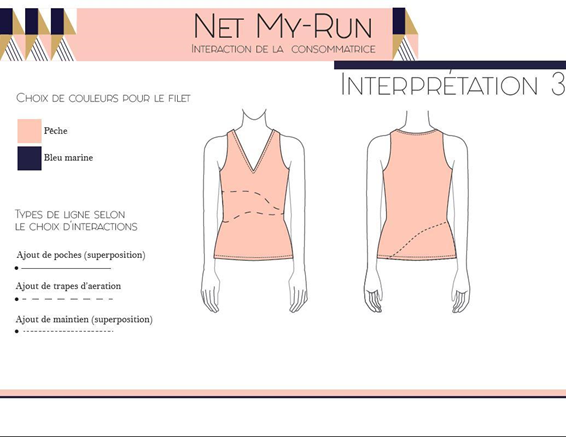

“NET-MY-RUN” (Description of case C (project 7))

The amateur is invited to customize sports training apparel by incorporating fabric netting tailored to her specific physiological needs and personal style. This customization can be achieved through:

The aspirant designer developed a collection of six stretch jersey training garments and created a platform that allows the amateur to use various types of lines to indicate the intended purpose of the fabric net additions on the garments (Figure 6) (Figure 7).

Figure 7 An illustration of interpretation represented by different dashed lines, from case C – NET-MY-RUN.

This project proved to be highly suitable and well-conceived due to the thoughtful integration of interventions. These interventions successfully combined stylistic choices with specific physical requirements, resulting in highly personalized performance solutions. The next section (“Findings and conclusions”) will further elaborate on these outcomes (Figure 8).

Not all responses from the aspirant designer surveys and amateur questionnaires are included in this section, as some pertain solely to individual projects. This conclusive section aims to present and discuss overarching findings and draw general conclusions in order to objectively assess and evaluate the implementation of FDfDIY as a concept for ready-to-wear fashion design. The conclusions below are organized according to the initial research questions (see section “Research questions”) and are intended to directly address them.

Responses from aspirant designer surveys are referenced as “DSx”, where “x” corresponds to the survey question number. Similarly, responses from the amateur project questionnaires are referenced as “Aqp”, where “p” corresponds to the project number. Both documents, the aspirant designer survey (DS) and the amateur project questionnaire (AQ), are available for review.

Impact (Differences between FDfDIY and traditionally conceived ready-to-wear fashion design projects) (section “Research questions” (1))

The main distinction between ready-to-wear and FDfDIY lies in the aspirant designer’s empathy toward the participating amateur during the design process, as well as the level of the amateur’s involvement. Unlike traditional design approach, FDfDIY requires designers to anticipate the amateur’s DIY actions, fostering effective and intentional communication between both parties. In the FDfDIY model, the amateur’s project involves undertaking several preparatory steps, or “cycles” (Figure 1) that must be completed before the actual DIY activity can begin.

For the aspirant designers, involving the amateur into the design process was a stark contrast to their previous experiences, which were typically aligned with the industry-driven approach of offering new trends and subsequently fostering fashion consumption (source: Designer Survey Q1 (DS1)).

Limitations in offering a DIY design project and space to the amateur (corresponding to Research questions (2))

When comparing FDfDIY to traditional ready-to-wear fashion design, several limitations emerge from both the designer’s and the amateur’s perspectives. A key challenge lies in balancing the design spaces allocated to the amateur and the facilitating designer, as they are inherently interdependent.

Focusing specifically on the design limitations faced by a designer within the context of a FDfDIY project, several challenges emerge. First and foremost, the facilitating designer must take into account the design space and level of accessibility provided to the amateur. Consequently, the designer cannot approach the project in the same manner as they would in a traditional fashion design setting.

When examining the limitations faced by the amateurs, one can refer to the generic “Design for DIY boundaries” outlined by Hoftijzer39 (Figure 1). These boundaries, or “limitations”, encompass factors such as complexity, branded items, safety, and cost, which help determine whether a project is suitable for DIY. More concretely, in this study, the limitations encountered by amateurs while executing their DIY projects were identified as follows:

Participation as a new element of design (section “Research questions” (1) and (2))

A fundamental aspect of FDfDIY is the active participation of the amateur.

Correlations between (1) the facilitating designer’s intervention and (2) the amateur’s DIY experience (section “Research questions” (3))

As aforementioned in this paper, the preparatory activities of the facilitating designer and the amateur’s DIY experience are inherently interdependent. For instance, when the designer leaves multiple design decisions open-ended, the DIY space available for the amateur naturally expands, allowing for greater exploration and creative input.

The relevance of the FDfDIY concept to fashion design (section “Research questions” (4))

As stated in the introduction, the implementation of “Fashion Design for DIY” (FDfDIY) aims to enhance amateur’s awareness, knowledge, and skills while fostering a deeper overall appreciation of the design process and a stronger attachment to the final product.

Future directions (projects, education and research)

Educational course recommendations:

The surveys also examined the project within the context of an educational course. Aspirant designers shared their perspectives on “Fashion Design for DIY” both as a conceptual framework and as an hands-on exercise. Some interesting aspects emerged from their feedback.

Based on previous research that explored DIY fashion education as a way to develop agency and practical skills,2,3 integrating FDfDIY into fashion programs offers an opportunity to broaden pedagogical models beyond traditional design training. While many studies consider DIY mainly as a form of individual creative freedom, FDfDIY focuses more on facilitation and accessibility. In this approach, educators act as facilitators rather than only as sources of knowledge. In the future, this course could integrate a blended learning format, combining hands-on workshops with digital prototyping tools4 to improve student engagement and skill acquisition.

Research

Exploration of alignment with theories of human needs (Maslow).

According to Simmel,40 fashion is a pure product of social needs, driven by two basic fundamental instincts: the desire for imitation (belonging) and the need for differentiation (individuality). Later, Descamps41 examined fashion as a psychosocial phenomenon, questioning why, despite being born without clothing, humans carefully select their garments each day. While clothing serves primary functions such as protection, modesty (pudeur), ornamentation (parure), and language, including either one or a combination of these, fashion often incorporates hidden codes. These codes, expressed through materials, colours, forms, and embellishments, are implicitly understood and followed within different cultural contexts.

DIY and “design for DIY” are practices and methods specifically aimed at addressing human needs and desires, contrasting with the traditional top-down approach of industrial product design and ready-to-wear fashion. Given this perspective, it is both plausible and valuable to explore how the needs associate with fashion and clothing, alongside those of the amateur participating in a FDfDIY project, align with broader human needs, as outlined by Maslow,26 Ehrenfeld27 and Max-Neef.25

Future studies could further investigate this alignment, aiming to develop methods and models that facilitate Do-It-Yourself design while considering the human dimensions of participation, creativity, identity, and freedom. While previous research has emphasized the role of DIY in encouraging sustainable practices and consumer autonomy,5,1 FDfDIY expands this discussion by integrating both manual and digital approaches, thus reinforcing accessibility beyond skilled makers. Moreover, the structured facilitation model within FDfDIY provides a new perspective for analyzing co-design interactions between professionals and amateurs, an aspect still insufficiently explored in existing studies on open design.3 Future research could examine how these interactions influence design results, sustainability behaviours, and perception of authorship in the DIY fashion ecosystem.

Comparing design fields (Fashion Design for DIY vs. Product Design for DIY)

As previously discussed, product design and ready-to-wear fashion design share many similarities, particularly regarding their origins and the industrial practices they both follow. The “Fashion Design for DIY” experiments presented and evaluated in this paper offer an alternative approach to traditional practice in the fashion practice. The results (see section “A selection of project outcomes”) and key findings (see section “Findings and conclusions”) reveal several common denominators when compared to “Product Design for DIY”, with the framework model (Figure 1) serving as an initial point of reference.

However, as these two fields remain distinct, some clear divergences emerge and deserve further exploration.

Limitations of the study

Through this study, FDfDIY emerges as a framework that repositions the role of the designer, shifting from sole creator to facilitator, and expands the possibilities for amateur participation in fashion design. By bridging manual craftsmanship with digital tools, it enhances accessibility while fostering creative autonomy. As this approach continues to develop, further research could refine its methodologies, assess its impact on sustainability and authorship, and explore its applicability in other design fields. Ultimately, FDfDIY challenges traditional design hierarchies, opening new perspectives on how fashion can be conceived, produced, and experienced in a more inclusive and participatory manner.

Beyond its implications in education and independent creative practice, FDfDIY also presents potential for commercial applications. As Waal and Smal1 have discussed, fashion brands are increasingly exploring ways to integrate DIY elements into mainstream business models, responding to consumer demand for personalization, engagement, and sustainability. By offering modular or partially unfinished garments, brands could invite customers to participate in the final stages of creation, fostering a sense of ownership while reducing waste. Future research could examine how FDfDIY principles might be adapted by the industry, balancing mass production with opportunities for individual customization.43–52

Through this study, FDfDIY emerges as a framework that repositions the role of the designer, shifting from sole creator to facilitator, and expands the possibilities for amateur participation in fashion design. By bridging manual craftsmanship with digital tools, it enhances accessibility while fostering creative autonomy. As this approach continues to develop, further research could refine its methodologies, assess its impact on sustainability and authorship, and explore its applicability in other design fields. Ultimately, FDfDIY challenges traditional design hierarchies, opening new perspectives on how fashion can be conceived, produced, and experienced in a more inclusive and participatory manner.

This research has been supported by The Creative School, Toronto Metropolitan University.

None.

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.s

©2025 Martin, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.