Journal of

eISSN: 2374-6947

Research Article Volume 3 Issue 2

1Department of Internal Medicine, Second University of Naples, Europe

2Department of Endocrinology, Endocrinology and Metabolism Unit, Europe

3Department of Diabetes, San Gerardo di Monza Hospital, Europe

4Immune Response and Vascular Disease Unit, Nova University, Portugal

5Trento Province Health Service Agency, Rovereto Diabetes Care Center (TN), Europe

6Statistical Consultant for Associazione Medici Diabetologi (AMD), Europe

7BD Medical Systems: Diabetes Care, Erembodegem, Europe

Correspondence: Felice Strollo, Elle-Di, Endocrinology and Metabolism Unit, Europe, Tel +390 632 196 39

Received: March 29, 2016 | Published: April 27, 2016

Citation: Gentile S, Strollo F, Guarino G, et al. Factors hindering correct identification of unapparent lipohypertrophy. J Diabetes Metab Disord Control. 2016;3(2):42-47. DOI: 10.15406/jdmdc.2016.03.00065

Introduction: A correct injection technique is essential to prevent lipohypertrophy (LH) in people with diabetes mellitus (DM) and related glucose oscillations. However, features associated with missed LH identification are mostly unknown.

Aim of the study: to find out how lesion features influence LH identification and to assess patients’ awareness of the problem.

Materials and Method: 60 patients with LH lesions (36 F, 24 M, 56±13years of age) treated with four insulin shots per day were enrolled. All were blindly examined by four non-trained (NT) and four well trained (WT) health professionals (HPs) and filled in a questionnaire concerning their own experience.

Results: WT HPs were better at identifying LH lesions (OR 10.52 [4.34-25.50], p<0.001) but WT HPs were mostly wrong in the case of flat lesions located on the arms. By contrast, NT HPs failed identification of all possible lesion kinds. Patients’ answers to the questionnaire indicated a serious education gap concerning both insulin storage and injection technique, mostly dependent on inadequate follow-up by the care team.

Conclusion: To avoid most common mistakes including repeated shots into LH lesions and inappropriate insulin storage, continuous surveillance and exchange of information between care team and patients are necessary. To train patients on how to identify LH lesions by self-palpation and accurate skin inspection is crucial and can be easily done now according to structured education. The latter can improve clinical outcomes with little effort and can be further improved only by systematic and extensive utilization.

Keywords: diabetes, skin lesions, lipohypertrophy, insulin, injection, education, self-palpation, hyper-glycaemic, diabetes mellitus

Lipodystrophies (LDs) represent a typical complication of repeated drug injection into the same skin area.1 A correct injection technique is essential to avoid LDs in people with diabetes and the lack of LDs in turn allows good metabolic control by ensuring fully predictable insulin effects and by preventing the risk of repeated hypo- and hyper-glycaemic episodes.2-6 A large body of evidence is available concerning the rate of appearance of such lesions in people with diabetes but the way to correctly identify them is taken for granted and neglected.7-15 Moreover, information is still lacking on some key issues expected to strongly contribute to the high variability in LH rate reported in the literature, including features mostly associated with missed LH identification and the reasons why most of the time people with diabetes tend to use the same LH areas for insulin shots.

The purpose of this study was to fill this gap. Therefore we tried to understand how lesion size, location and shape influence the ability of trained staff to identify LH areas. At the same time we investigated patients’ perspectives in terms of awareness of the problem, injection site rotation and repeated training on identification and avoidance of LH areas to check whether injection errors might depend on education shortage linked to poor message reinforcement activities.

The research protocol was fully approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Association of Diabetes Specialists (AMD). Participants provided a written informed consent to participate in the study specifically prepared according to a procedure approved by the Ethics Committee and sample size was preliminary calculated according to standard statistical procedures.

Sixty patients consecutively referring to our clinic and treated with four insulin shots per day for at least two years were enrolled as having LH lesions at one or more injection sites. Before starting insulin treatment, all patients had received careful education concerning best recommended injecting techniques6,16 but up to the time of the study they were provided with no further educational training. The protocol was prepared according to the Helsinki declaration and approved by the local Ethics Committee. The main clinical features of people participating in the study are given in Table 1 and may be briefly summarized as follows: 36 were females, age was 56 ±13 years, daily insulin dosage was 58 ± 14 IU under a four daily shot regimen, and the diabetes duration was 7±2 years (range 5-9).

n=60 |

|

Female gender |

60% |

BMI (Kg/m2) |

29.2±2.3 |

HbA1c (%) |

8.5±0.9 |

Lipohypertrophy site |

|

Abdomen |

40% |

Arm |

35% |

Thigh |

25% |

Lipohypertrophy type |

|

Flat |

55% |

Protruding |

45% |

Lipohypertrophy size |

|

Diameter (cm) |

4.7±1.3 |

Table 1 Characteristics of the population under study

Preliminarily each LH was identified by an experienced physician external to the study, then High-frequency B-mode skin ultrasound scans (USS) were performed by three different ultrasound scan (US) operators using the linear 20 MHz probe (Philips HD3) to validate the diagnosis of LH and to define single lesion size and features, including thickness and texture, as previously described.17 Each patient was blindly examined by four non-trained (NT) and four well trained (WT) health professionals (HPs) consisting of non-specialized and specialized nurses, respectively. NT HPs were given no advice on how to inspect and touch the skin but were simply asked to try and identify lesions several times in each expected location by doing their best to examine the injection sites. By contrast, WT HPs were taught how to correctly define LH lesions by performing a careful examination of typical injection sites according to the standardized palpation method described elsewhere.17

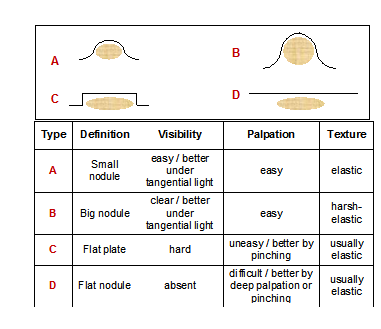

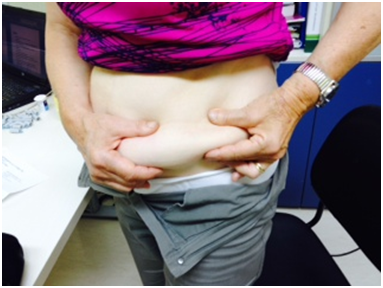

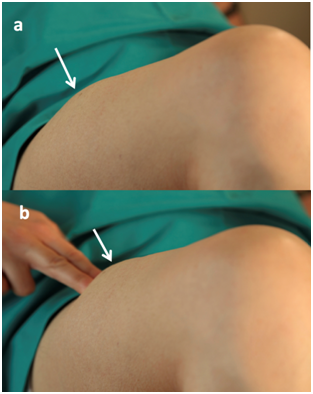

Briefly, each interested area was inspected using direct and tangential light against a dark background, and a thorough palpation was performed (slow circular and vertical finger tip movements followed by repeated horizontal attempts on the same spot). HPs were also advised to be gentle while touching the skin at the beginning and start to progressively increase finger pressure thereafter. They were also suggested to perform the pinch maneuver when perceiving a harder skin, to confirm their first impression by comparing the thickness of the suspected spot to that of surrounding areas (Figure 1). In some cases an abdominal LH lesion can be easily identified by the patient himself (Figure 2), but small and flat lesions can be - and actually were - investigated by repeating all above mentioned palpation maneuvers at least three times in a row (Figure 3).

All patients were asked to anonymously fill in a 6-item multiple choice, single option questionnaire also to assess whether poor injection techniques responsible for LH development might depend on education shortage. On the basis of patients’ questionnaires, the diabetes care team implemented an eight-by-eight people educational recall course consisting of theoretical and practical hints concerning correct injections techniques, different insulin pen needles, appropriate injection site rotation habits and insulin storage requirements. HbA1c levels were checked immediately before and 3 months after the course.

Continuous variables were reported as means ± SD’s and were compared between groups by Student’s t-test for independent samples or analysis of variance (ANOVA) as needed. Non-parametric tests were used when appropriate. Categorical variables were summarized as rate or percentage and their bivariate association was evaluated by Chi-square or Fisher exact test. Patients were grouped and compared according to their LH identification rate characteristics, namely by considering those identified by all HPs vs those identified by none of them. The proportion of patients correctly identified was estimated by using a logistic mixed model with patients fitted as random. The ability of WT vs NT HPs to detect LH was evaluated by a mixed and ordinary logistic model (respectively, for the analysis at the single HP level and at the level of full recognition by all HPs). Odds Ratios (ORs) for LH were given with 95% confidence interval (CI). The analyses were carried out using STATA software, Version 12 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA). P-values <0.05 were taken as statistically significant.

The clinical characteristics of 60 insulin requiring subjects are described in Table 1. All had LH at various sites, as well as, lesions of different type and size. Table 2 clearly shows the percentages of HPs correctly identifying LH lesions depend on their different features.

Non-Trained (%) |

Well Trained (%) |

p |

|

Size |

|||

Diameter >4cm |

83 |

98 |

<0.001 |

Diameter <4cm |

50 |

95 |

<0.001 |

Shape |

|||

Protruding |

83 |

100 |

<0.001 |

Flat |

52 |

93 |

<0.001 |

Site |

|||

Thigh |

75 |

100 |

<0.01 |

Arm |

39 |

89 |

<0.001 |

Abdomen |

84 |

100 |

<0.01 |

Overall |

66 |

96 |

<0.001 |

Table 2 LH identification results obtained by Well Trained and Non-Trained health professionals as referred to skin lesion shapes, sites and sizes (% stays for identification rate)

To assess the ability to identify LH, data were analysed by three categories:

Patients identified by both groups displayed a higher BMI and had LH lesions mostly characterized by arm localization, flat morphology and a smaller diameter. Patients identified only by WT displayed intermediate characteristics. WT HPs were better at identifying LH lesions with an OR of 24.86 (10.61-58.27), p <0.001, in the operator-based analysis and an OR of 10.52 (4.34-25.50), p <0.001, when taking into account fully correct identification by all HPs. The comparison between patients correctly identified and those not identified by the two groups of HPs is described in Table 4.

Failure to Recognize Skin Lesions by |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

WT and NT |

Only NT |

No failure |

||

n=9 |

n=30 |

n=21 |

p |

|

Female gender |

67% |

70% |

43% |

0.147 |

BMI (Kg/m2) |

30.4±2.3 |

29.7±2.2 |

27.9±2 |

0.005 |

Lipohypertrophy site |

||||

Abdomen |

0% |

40% |

57% |

0.011 |

Arm |

100% |

30% |

14% |

<0.001 |

Thigh |

0% |

30% |

29% |

0.177 |

Lipohypertrophy type |

0.001 |

|||

Flat |

100% |

60% |

29% |

|

Protruding |

0% |

40% |

71% |

|

Lipohypertrophy size |

||||

Diameter (cm) |

4.0±0.9 |

4.1±1.0 |

5.8±1.2 |

<0.001 |

Table 3 Characteristics of patients with unrecognised LH by Well Trained (WT), Non-Trained (NT), and both health professionals

Non-Trained |

Well Trained |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

No LH |

LH |

No LH |

LH |

|||

n=39 |

n=21 |

p |

n=9 |

n=51 |

p |

|

Female gender |

69% |

43% |

0.047 |

67% |

59% |

0.729 |

BMI (Kg/m2) |

29.9±2.2 |

27.9±2 |

0.002 |

30.4±2.3 |

29±2.3 |

0.091 |

Lipohypertrophy site |

0.035 |

<0.001 |

||||

Abdomen |

31% |

57% |

0.047 |

0% |

47% |

0.008 |

Arm |

46% |

14% |

0.014 |

100% |

24% |

<0.001 |

Thigh |

23% |

29% |

0.639 |

0% |

29% |

0.095 |

Lipohypertrophy type |

0.003 |

0.003 |

||||

Flat |

69% |

29% |

100% |

47% |

||

Protruding |

31% |

71% |

0% |

53% |

||

Lipohypertrophy size |

||||||

Diameter (cm) |

4.1±1 |

5.8±1.2 |

<0.001 |

4.0±.9 |

4.8±1.4 |

0.034 |

Table 4 Characteristics of patients fully missing (no LH) or fully receiving (LH) lesion identification by all Well Trained (WT) or Non-Trained (NT) health professionals

Site, type and size of LH seem to be the discriminating items, still at different levels, with respect to missed identification by the two groups of HPs. In fact, WT HPs who were unable to identify LH’s were always wrong in the case of lesions located on the arm and of the flat type. By contrast, NT HPs failed identification of all possible kinds of lesions. These differences are relevant in terms of our understanding of where training provides people with the best benefits at the moment in terms of LH identification and where training has to be improved.

The answers to the questionnaire are described in Table 5. The main reason why patients continue to inject insulin into LH lesions is the absence of pain, followed by “ergonomic-like” habits leading people to repeat the same movement while shooting insulin several times a day. The majority of patients reported not to have been trained on how to inject insulin and those who were educated mostly do not remember who trained them. Over 50% of patients kept all insulin pens in the refrigerator regardless of being currently used or stored and therefore erroneously and constantly caused thermic shock to their warm skin by using a cold solution.

Question n. 2 might seem somewhat repetitive but was chosen to indirectly confirm the answer given to question n. 1. In fact patients confirmed that the main reason why they went on injecting insulin into LH areas was that this way shots were painless, the other reason was that they found it easier to inject insulin the same way several times a day.

The answers given by the patients clearly indicate a serious lack of education. This mostly depended on a wrong habit during follow-up visits. In fact it was possible to analyze all medical records, which always reported a training session dedicated to insulin shots at the first visit while no mention was present of any training recalls there neither after nor of any periodic injection site examinations. As a matter of fact, HbA1c went down in 85% patients after the educational recall course (7.7±0.5 % at 3 months vs 8,5 ± 0,9 % at baseline; p<0.05).

n=60 |

|

1. Why do you continue to inject insulin into a LH area? |

|

It hurts less |

37% |

It suits me |

33% |

I think that somewhere else it would not work |

17% |

I do not know |

13% |

2. Is it less painful when you inject insulin into a LH area? |

|

Yes |

82% |

No |

10% |

Indifferent |

8% |

3. Did anyone teach you how and where to inject insulin? |

|

Yes |

22% |

No |

47% |

I've seen it done in hospital |

22% |

I saw it on the website |

2% |

I learned it from other patients |

8% |

4. Did anybody check your injection sites after the first education session (if any)? |

|

Yes |

18% |

No |

82% |

5. Do you store your pen in the refrigerator and inject insulin immediately after taking it out of the fridge? |

|

Yes |

53% |

No |

47% |

6. If the answer to question n. 5 is yes, who told you to do so? |

|

The pharmacist |

63% |

My doctor |

9% |

No one but I have seen it done |

16% |

I thought it was the best way to keep insulin fully active |

13% |

Table 5 Results of the questionnaire

Despite guidelines and recommendations emphasizing the need to implement proper insulin injection habits,6,13,16-19 many papers raise some concerns regarding the high rate of LH lesions causing an extremely poor metabolic control and eventually leading to severe health consequences to patients with diabetes.7-15

Therefore teaching patients how to examine their own skin and identify LH areas might be the best way to implement a correct injection technique and have a pivotal role on preventing huge blood glucose fluctuations and consequent long-term complications.19 Nevertheless, almost no indications are available in the literature concerning correct identification of LH. The data of the present study confirm the highly significant difference between specifically trained and non-trained HPs in terms of LH identification. However, flat, small and arm-localized LH lesions can escape even the most careful observation. These kinds of LH require the HP to have expertise, personal talent and patience, as well as to adopt the right methodology as carefully as possible.

The high LH rate reported in the literature points to an educational defect either at the starting point (which does not seem to be the case in our patients) or during follow-up. In fact, patient answers indicate that in most cases initial information is lost during the years and never refreshed. Medical records seem to confirm this. Adequate educational actions should be taken to let patients fully understand the relationship between missed injection site rotation and LH development.13 And even more should be done to teach patients that, when injected into LH areas, insulin is absorbed erratically, causing huge glycaemic oscillations and increasing the risk for hypoglycaemic events.16,20

However, it is imperative that all doctors and HPs in general, as well as patients themselves become experts in skin assessment to avoid repeated shots into lesions and inappropriate insulin storage.19 To avoid such mistakes, a constant surveillance attitude and a continuous exchange of information between care team and patients are necessary. Answers to our questionnaire are somewhat discouraging and pitiless as the spotlight was on our inability to focus systematically on most basic pieces of knowledge which form the basis of patients’ daily life. Due to this it becomes crucial to understand why patients forget the few initial educational notions we provide and why we face so many difficulties in patient education. This is further confirmed by the results of the educational recall effort performed by our group, which turned out to be effective in terms of glucose control with a significant decrease in HbA1c levels after a while (7.7±0.5 % at 3 months vs 8,2±0,6 % at baseline; p<0.05).

Diabetes HPs have little time to devote to a growing number of diabetics, have few organizational resources (dedicated staff, space, pathways and time) and in some countries (like Italy) educational activities are not paid for.21 In fact, only 49% of people with diabetes reported having participated in a diabetes education program.22 Moreover the involvement of family members is crucial especially to get a significant reinforcement of all educational messages; nevertheless only few family members participate in any diabetes educational programs or activities (23.1%), with the highest participation rates found in Denmark followed by Canada, USA, Poland, Germany, Algeria and China.23 In addition to that, depression is rather common among people with chronic diseases including diabetes and it might be defeated somehow by a strong family participation in educational programs too. It might be an additional factor playing a major role in poor adherence to treatment rules. This emotional disorder remains under-assessed by healthcare professionals13 and has not been addressed in our study.

In any case, despite the many possible factors interfering with individual patient attitudes towards disease management and with our team ability to cope with them, the present paper clearly shows that we have to teach our patients proper injection techniques and repeatedly verify what they learned and what they understood in terms of eventually occurring severe complications of inadequate habits. The results we all can expect from such a challenge as part of the group care model24 are really exciting and can represent, for instance, a good complement to structured educational tools like conversation maps.25 The significantly improved metabolic control after a refresher shows the high short term efficacy of and gives support to what reported by other Authors.14 However we neither know their long term efficacy nor the number of and the recommended interval among recall courses required to keep injection technique and HbA1c levels at the appropriate levels. To answer these questions further specifically designed studies are warranted.

In fact, the role of continuing patient training is crucial to avoid erroneous injection modalities especially in those individuals who are put at increased risk for LH by different factors, including longer disease duration, high daily insulin dose requirement, poor socio-economic and/or cultural conditions, loneliness, depression or dementia, as well as, living in retirement homes, nursing homes or hospices.13,14,26

In conclusion we showed it is extremely productive to train both HPs and patients on how to identify LH lesions. The latter, in fact, should perform accurate skin inspection and self-palpation before insulin shots. It can be easily done at the moment according to freshly published examples of structured education that can improve clinical outcomes with little effort and that can be further improved only by systematic and extensive utilization.

None.

Author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

©2016 Gentile, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.