Journal of

eISSN: 2574-9943

Research Article Volume 3 Issue 1

Department of Dermatology, Muzaffarnagar Medical College, India

Correspondence: Avneet Singh Kalsi, Department of Dermatology, Muzaffarnagar Medical College, India, Tel 9170 8740 3020

Received: January 01, 1971 | Published: February 1, 2019

Citation: Kalsi AS, Thakur R, Kushwaha P. Extensive tinea corporis and tinea cruris et corporis due to trichophyton interdigitale. J Dermat Cosmetol. 2019;3(1):16-20. DOI: 10.15406/jdc.2019.03.00108

Background: India is facing a gruesome epidemic-like scenario of chronic, extensive and recalcitrant dermatophytosis for the past 5-6 years. Dermatophytosis, also commonly known as tinea, used to be considered as trivial infection and was easy to treat. Unethical and irrational mixing of antibacterial and topical corticosteroid with antifungal agents has been instrumental for this extremely challenging situation. Applying such topical preparations for the treatment of dermatophytosis, without any oral antifungal agents can result in extensive lesions and also, fungal resistance.

Objective: To find out the cause and dermatophyte species associated with the extensive lesions of tinea corporis.

Patients and methods: A study was carried out in the tertiary care centre by the Department of Dermatology and Microbiology during the period starting from October 2016 to April 2017. A total of 158 patients were consented. Any patient with clinical findings of Tinea corporis and KOH and/or culture positive was enrolled in the study. A detailed history was taken. Samples were collected after cleaning the part with 70% alcohol and all KOH positive or negative samples were inoculated on Sabouraud’s dextrose agar supplemented with chloramphenicol and cycloheximide. The culture plates were incubated at 25°C and were observed for four weeks. Lacto Phenol Cotton Blue (LPCB) mounts were prepared to study the microscopic structures in detail. Other tests like urease and in vitro hair perforation tests were also set up to differentiate Trichophyton interdigitale from Trichophyton rubrum.

Results: A total of 149(94.30%) were KOH and 158 (100%) were culture positive. We isolated only Trichophyton interdigitale from 158 patients. None of the patients was HIV positive, 6patients (4%) had diabetes. About 70% of the patients gave history of using various combinations of antifungal, antibiotic and topical steroid creams and nearly 10% used pure steroid creams. Rest did not know the name of the cream they applied.

Limitations: Molecular characterization was not done to see genetic relatedness.

Conclusion: Topical steroid lowers the local immunity and contribute to the extensive and atypical lesions. Dermatophytosis has acquired epidemic proportions in this region of western UP. Misuse of unregulated combinations of steroid is rampant in this region.

Keywords: trichophyton interdigitale ( interdigitale), sabouraud’s dextrose agar, fixed drug combinations, over the counter

LPCB, lacto phenol cotton blue; SDA, sabouraud’s dextrose agar; FDCs, fixed drug combinations; OTC, over the counter; KOH, potassium hydroxide

Dermatophytosis commonly known as tinea is caused by the three genera of dermatophytes: Trichophyton, Epidermophyton and Microsporum. Tinea corporis is the most common clinical form and next in frequency is tinea cruris.1 Most of the infections are caused by Trichophyton rubrum (T. rubrum) and Trichophyton interdigitale (T. interdigitale). There are only few case reports of tinea corporis due to Trichophyton violaceum.2‒4 One case of tinea corporis due to T. tonsurans has been reported by Rao et al.5 Recently, there have been reports from other countries, United Kingdom,6 Japan,7,8 Germany,9 Switzerland10 and Belgium,11 about tinea corporis due to Arthroderma benhamiae, which is a telomorph state of zoophilic Trichophyton mentagrophyte. Tinea cruris is commonly caused by T. rubrum and T. interdigitale, but Kumar et al.12 have reported four cases of pubogenital dermatophytosis due to T. violaceum.12

The classical lesion of tinea corporis present as an annular erythematous plaque with slightly elevated scaly borders with central clearing. The present clinical scenario of tinea corporis and tinea cruris are much different. We hardly get any case of tinea corporis or tinea cruris with classical appearance. Usually, patients present with multiple extensive lesions and at times with bizarre appearance and may pose diagnostic challenges. This current epidemic like scenario is due to inappropriate combination of topical corticosteroid mixed with antifungal and antibacterial creams also known as fixed drug combinations (FDCs) and are easily available as over the counter (OTC) and do not require the prescription of a dermatologist or a qualified doctor.

The Department of Dermatology and Microbiology of Western Uttar Pradesh, India conducted the study at a tertiary care center during the period starting from October, 2016 to April, 2017. A total of 158 patients were consented. A detailed history in the form of age, sex, site, duration, treatment taken, and probable source of contact was taken. Patients were instructed to come for the collection of the samples after taking bath with unscented soap and water and without applying any cream or ointment and were sent to the mycology laboratory for the collection of the samples. Samples were collected after scrubbing the site with 70% alcohol. The scales were collected from the periphery with the help of sterile scalpel blade in a sterile petri dish. Swab stick was used for sample collection from the infected pustular lesions.

All the samples were examined for fungal elements in Potassium hydroxide (KOH) 20% mount under high power of the microscope. Both the positive and negative samples were inoculated on Sabouraud’s Dextrose Agar supplemented with chloramphenicol and cycloheximide. The culture plates were incubated at 25°C for four weeks and were observed every week for growth. Lactophenol cotton blue (LPCB) mounts was prepared to study the microscopic structures in detail. Other tests like urease and in vitro hair perforation tests were done to differentiate T. interdigitale from T. rubrum. Clinically typical or clinically suspicious (atypical structures), yet KOH positive as well as culture positive cases of tinea corporis and tinea cruris et corporis of all ages and both genders were incorporated into the study.

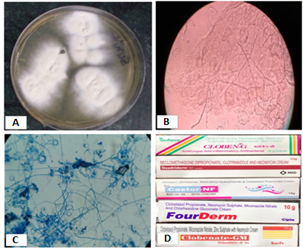

Colonies of T. interdigitale were seen, which were white in colour and of cottony consistency on obverse and beige to brown on reverse (Figure 1A). T. interdigitale was isolated from all of our patients. On KOH examination, branching septate hyphae were seen (Figure 1B). Lacto Phenol Cotton Blue mounts showed septate fungal hyphae, with numerous sphericial microconidia arranged in grape-like clusters, cigar shaped macroconidia and spiral hyphae (Figure 1C). A total of 158 patients were enrolled for the study. Male patients were 98 (62%) and 60 (38%) were females. A total of 149(94.30%) were KOH positive and all 158(100%) were culture positive.

Figure 1 (A) Cottony beige colored growth of T. interdigitale after one week of incubation on SDA at 25°C; (B) Septate branching fungal hyphae in KOH mount; (C) Lacto Phenol cotton blue mount showing spiral hyphae, microconidia in grape like clusters and pencil shaped macroconidia (D) FDCs available as OTCs.

Percentage of males and females suffering from tinea corporis and tinea cruris was higher in the age group 16-30 years. In this study, percentage of females suffering from tinea corporis was higher i.e. 52.63% and it was 48.38% among males. But, the percentage of tinea corporis et cruris was higher among males 61.11% and 45.45% among females (Table 1). No case of tinea corporis et cruris was seen among males and females above 60 years of age and in females in the age group 0-15 years. None of the patients had any inflammatory lesions or the involvement of lymph nodes. The lesions were extensive and atypical.

Age in years |

Male |

Female |

||

T. corporis TCM |

T. corporis et cruris (TCM et cruris) |

T. corporis(TCF) |

T. corporis et cruris (TCF et cruris) |

|

0-15 |

04(6.45%) |

02(5.55%) |

04(10.52%) |

- |

16-30 |

30(48.38%) |

22(61.11%) |

20(52.63%) |

10(45.45%) |

31-45 |

20(32.25%) |

08(22.22%) |

08(21.05%) |

06(27.27%) |

46-60 |

06(9.67%) |

04(11.11%) |

04(10.52%) |

06(27.27%) |

>60 |

02(3.22%) |

- |

02(5.26%) |

- |

Total |

62(100%) |

36(100%) |

38(100%) |

22(100%) |

Table 1 Age and gender wise distribution of Tinea corporis and Tinea cruriset corporis

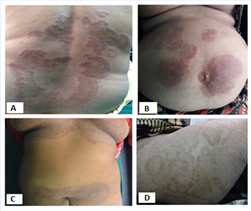

We found patients with many atypical lesions: Extensive bilateral extensive erythematous infiltrated lesions (Figure 2A), polycyclic erythematous squamous lesions with a vesicular border on abdomen and under breast in a female patient (Figure 2B), and one female patient had extensive bilateral erythematous scaly plaques without central clearing over and under the breast and she was also having tinea corporis et cruris (Figure 2C). One female patient presented with tinea pseudoimbricata, which represented as centrifugal growth of dermatophyte with central clearing and she also had extensive tinea cruris (Figure 2D & Figure 3).

Figure 2 (A) A 23-years old lady with bilateral extensive erythematous infiltrated lesions over the back (B) A 42-years old female with polycyclic erythematous squamous lesions with a vesicular border on abdomen and under breast (C) A 26-years old female with extensive bilateral erythematous scaly plaques without central clearing over and under breast, also having tinea cruris et corporis (D) Tinea pseudoimbricata: Dermatophyte proceeds centrifugally though without sufficient central clearing.

The altered forms of tinea corporis are due to use of topical corticosteroids along with antibiotics and antifungal agents. The lesions become extensive without central clearance and at times acquire bizarre appearance and pose diagnostic challenges and mimic many dermatological conditions, e.g. psoriasis, granuloma annulare, pityriasis rosea, and Hansen’s disease. According to some studies in India, tinea corporis and tinea cruris are the most common clinical presentation in this country and these studies invariably found T. rubrum to be the most common isolate.13 There are two small studies, which have reported tinea unguim as the commonest presentation.14,15

Those who are prone to dermatophytic infections include:

Western U.P. has hot and humid climate. Also the current fashion trends of wearing close-fitting synthetic garments also contribute to tinea cruris and tinea corporis. With the use of topical corticosteroid, the lesions become extensive, and it may spread from groin upward to involve abdomen and results in tinea cruris et corporis or tinea corporis may extend downwards to involve groin, genitalia, thighs and buttocks. When tinea corporis extends toward groin, it is called tinea corporis et cruris. We have used the two terms of tinea corporis et cruris and tinea cruris et corporis synonymously. The merging of the lesions is common due to extensive spread due to use of FDCs. We found tinea corporis to be the most common clinical form (61.20%) and next in frequency were tinea cruris (24.34%).1 But, all of our cases were due to T. interdigitale. We did not get any case either due to T. violaceum or T. rubrum. According to our study conducted recently, 98% cases were due to T. interdigitale and one due to T. rubrum and one case of tinea capitis due to T. violaceum.1

Similar to study by Verma et al.16,17 the clinical forms i.e., tinea faciei and tinea genitalis, were reported with increased frequency even in our previous studies. Also, we have discussed female tinea genitalis.18‒20 We first reported an outbreak of tinea cruris and tinea genitalis due to T. interdigitale in 2016.19 Since the mycology section of microbiology was personally involved in the collection of samples, positivity of KOH mount and culture was very high as compared to most of the studies in India. Also the lesions being extensive and T. interdigitale is a rapidly growing fungus. The predominant species in neighboring regions is given in Table 2 and in neighboring countries is given in Table 3.

Place of study |

Author |

Year |

Predominant species |

Allahabad, Uttar Pradesh |

Narain U et al.21 |

2018 |

T. mentagrophytes 52.47% |

Banaras, Uttar Pradesh |

Mahajan S et al.22 |

2016 |

T. mentagrophytes 75.9% |

Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh |

Sahai S et al.23 |

2011 |

T. mentagrophytes 25% |

Chandigarh |

Pathania S et al.24 |

2017 |

T. mentagrophytes 40% |

Delhi |

Kaur R25 |

2017 |

Skin: |

Bihar |

Choudhary et al.26 |

2016 |

T. rubrum 62.3% |

Amritsar, Punjab |

Kansra S et al.27 |

2016 |

T. mentagrophytes 46.43% |

Ludhiana, Punjab |

Gupta et al.28 |

1993 |

T. rubrum 42.42% |

Table 2 Predominant species in the neighboring regions

Place of study |

Author |

Year |

Predominant species |

Rawalpindi, Pakistan |

Shujat U et al.29 |

2014 |

T. interdigitale 3.9% |

Yan’an Area, China |

Ma XN et al.30 |

2016 |

T. rubrum |

Kathmandu, Nepal |

Paudel D et al.33 |

2015 |

T. rubrum 58.33% |

Sri Lanka |

Attapattu MC34 |

1998 |

1974 – 1978 |

Bhutan |

Lee WJ et al.35 |

2015 |

T. rubrum 88.35% |

Table 3 Predominant species in the neighboring countries

There is lack of qualified dermatologists in the country especially in the rural set up. But, it has been observed that even trained physicians and dermatologists are prescribing the wrong strength of TC or for the wrong indication.36 At times, dermatologists, doctors or unqualified practioners prescribe FDCs without confirming the diagnosis. None of the patients had either inflammatory lesion or involvement of the lymph nodes. Due to extensive and multiple lesion, patients are very infectious. Such patients require both topical and oral antifungal treatment for a longer period than the usual period of treatment. When the patients get clinically cured, confirmation of mycological cure is important. Moreover, all family members should be treated simultaneously.

Unfortunately, the poor patients cannot afford this expensive treatment and they just procure the cheap FDCs sold as OTC, which doesn’t benefit the patients, but prolong the misery. This can result in chronic, recalcitrant type of dermatophytosis and may give rise to fungal resistance. There is lack of accredited laboratories in the country and also, there are few laboratories in the country, where antifungal susceptibility is done. Also, dermatology department should have facility for doing Dermoscopy and should find out whether there is involvement of vellus hair, which is an indication for giving systemic antifungal treatment.37

This epidemic like scenario due to T. interdigitale needs immediate attention of dermatologists, microbiologists, government, public health department, drug regulatory authorities and most importantly general population. Availability of FDCs sold as OTC should be banned. The government must provide free treatment to the poor people. Awareness should be created among people through electronic media and newspaper.

Authors thank all the individuals who contributed to this study. No funding was received for the study.

Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

©2019 Kalsi, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.