Journal of

eISSN: 2373-633X

Research Article Volume 10 Issue 5

1Center for Health Research, Kaiser Permanente Northwest, USA

2Permanent Dental Associates, USA

Correspondence: Lisa A Waiwaiole, Center for Health Research, Kaiser Permanente Northwest, 3800 North Interstate Avenue, Portland, OR 97227 USA, Tel 503 335-2454

Received: October 09, 2019 | Published: October 28, 2019

Citation: Waiwaiole LA, Henninger ML, Pihlstrom DJ, et al. Dental provider vaccination recommendations, a parent accepted strategy for disease prevention. J Cancer Prev Curr Res. 2019;10(5):126-131. DOI: 10.15406/jcpcr.2019.10.00404

Introduction: Coverage rates for recommended adolescent vaccinations such as HPV and influenza (flu) are far below the 80% Healthy People Target. Promoting vaccination in nontraditional settings such as the dental office may provide a unique opportunity to improve vaccination rates and prevent cancer.

Methods: In a cluster randomized trial of 16 Kaiser Permanente Northwest (KPNW) Dental clinics, dental teams were randomized to deliver an intervention to recommend vaccination to 11-17-year-olds who were due for a recommended vaccination, or to deliver usual care. We mailed surveys to the parents or guardians of adolescents asking whether they received a vaccine recommendation during their dental visit and assessing their comfort with the intervention.

Results: Nearly 64% of 11-17-year-olds who had a dental visit during the study period were due for one or more recommended vaccination. Most (72%) parents indicated that they were either comfortable or neutral about dental providers making vaccine recommendations. Over two-thirds (69%) of parents who recalled receiving the specific vaccine recommendation reported that their child subsequently received some or all the vaccines recommended during the dental visit or that they planned to do so. However, a sizeable minority of parents, 31%, reported that they did not plan to follow up with recommended vaccinations.

Discussion: Most parents are accepting of dental providers making vaccination recommendations. Promoting vaccination in alternative settings such as dental clinics may be a promising technique to prevent cancer, other disease and death through closing vaccination gaps.

Recommended vaccines for adolescents between the ages of 11-17 years in the United States (U.S.) are tetanus-diphtheria-acellular pertussis (Tdap), meningococcal conjugate (MCV4), human papillomavirus (HPV), and seasonal influenza (flu). While U.S. vaccine coverage rates for Tdap and MCV4 approach Healthy People target goals of 80%, coverage rates are 43% for HPV1 and 49% for flu.2 The American Academy of Paediatrics cites the need for improvement in vaccination rates.3 A model suggests that increasing HPV vaccine coverage to 80% for 13 birth cohorts of U.S. girls 12 and under could avoid 53,300 lifetime cervical cancer cases.4 Given that most flu-associated pediatric deaths are in children who were not vaccinated, estimates show that vaccination could reduce risk of death by 50% for children in high-risk categories and two-thirds for children with no high-risk conditions.5 With pertussis disease rates increasing,6 increased vaccination coverage could prevent death and disease. Renewed strategies are needed to address low vaccination rates.

Although we know that vaccines prevent death and disease, achieving optimal uptake remains a major hurdle. Parents often list provider recommendation as the top reason for receiving or intending to receive a vaccine7 and has been shown to significantly increase vaccination uptake.3 However, the power of primary care provider recommendations may be limited for adolescents, who have fewer routine medical visits than younger children.8–10 Despite strategies such as patient reminder and recall systems, electronic health record prompts, and educational programs, vaccination rates have been slow to increase.3 One suggested solution is for health care settings beyond traditional primary medical care, such as pharmacies and dental offices, to provide vaccines or vaccine recommendations. These non-traditional settings could “augment the vaccination efforts of more traditional settings”.11 Surveys indicate parents are accepting of alternative settings such as school-based health centers, emergency departments, pharmacies, or medical specialty offices for vaccinations.3,12

Dental clinics are one example of a non-traditional setting that may provide additional opportunities for a trusted provider to give a strong recommendation for a variety of preventive care services.13 Dental clinics and vaccinations could be a particularly good fit for vaccine recommendations, given the rise in oropharyngeal cancers associated with HPV14 and the recent interest in medical dental integration, a concept where dentists and medical providers work together to ensure wholistic patient care by recommending appropriate preventive care across disciplines as needed.15–17

Since parental attitudes are a primary factor in determining whether children are vaccinated,6 the success of any vaccine recommendation program will depend heavily on parental attitudes, beliefs, and acceptance of such an approach.18 There has been limited research on vaccination in dental settings, although one study of a program that offered the HPV vaccine in a dental setting19 found that parents had low comfort with dentists administering the HPV vaccine, but higher levels of comfort with dentists providing education and promoting the vaccine. To investigate parent comfort with vaccination recommendations for adolescents in a dental setting, we conducted a parent survey as part of a cluster randomized trial of an intervention that encouraged dental team members to make strong vaccine recommendations to adolescents and/or their parents when the adolescents were due for one or more vaccinations at the time of their dental visit. During the intervention period, we surveyed parents in the intervention group to confirm their receipt of the intervention, assess their attitudes about receiving vaccine recommendations at a dental visit, and determine whether the adolescent had subsequently obtained the vaccine(s) that were recommended at the dental visit.

Setting

This study was conducted at Kaiser Permanente Northwest (KPNW), an integrated healthcare delivery system in Oregon and southwest Washington currently serving over 600,000 members that offers both medical and dental insurance and care. The medical and dental clinics have access to a shared electronic medical record (EMR) that captures patient visit information and vaccination history. In 2014, there were 46,154 members between the ages of 11 and 17. Thirty-seven percent of these adolescent members (16,887) had both medical and dental insurance. This study was approved by the KPNW Institutional Review Board.

Intervention

We randomized 16 KPNW dental clinics to intervention or usual care from October 2015 to September 2016. Eight of the dental clinics were stand-alone while eight shared a building or were located on a campus with ambulatory medical care. Dental staff in each of the 8 intervention clinics were asked to attend a 45-minute educational presentation during a regularly scheduled department meeting. The presentation described adolescent vaccinations and provided detailed instructions for carrying out the intervention protocol. The primary intervention components included a personalized letter informing patients of vaccinations that were due, a brochure containing vaccine information and locations where vaccines could be administered, and instructions to dental team members to verbally recommend necessary vaccines, with suggested language provided. A Dental Adolescent Immunization Study (DAIS) Toolkit, which contained additional information about vaccines and frequently asked questions, was housed at each clinic (intervention materials can be found at https://research.kpchr.org/research/our-researchers/allison-naleway/dental-adolescent-immunization-study-dais). Staff in usual care clinics were only asked to distribute personalized letters informing patients of vaccinations that were due. Providers in the intervention group were instructed to not share intervention materials with usual care clinics to prevent contamination.

Participants

To assess parental attitudes about receiving immunization recommendations from their dental provider, we mailed surveys (n=907) to the home address of parents or guardians of a subset of 11-17-year-olds who had a dental visit within the last several months in an intervention dental clinic; parents of adolescents who visited usual care clinics were not surveyed. To be eligible for the intervention, children had to be at least 11 years of age and not older than 17 years and 11 months old one week prior to their dental visit; have both medical and dental insurance with KPNW; and be due for at least one of the following four vaccines: flu (one annual dose), Tdap (one dose at age 11-12), HPV (first, second, or third dose; the change to 2 HPV doses up to 14 years, 3 doses for 15+ years was not implemented when this study was completed) or MCV4 (initial dose or booster).

Evaluation

The parent survey was a 15-item, self-administered, questionnaire that assessed whether the patient received written or verbal vaccine recommendations during their dental visit, comfort with delivery of vaccine recommendation or other preventive health services from their dental provider, intent to follow-up on recommended vaccinations and demographic information. The survey instrument was developed by members of the study team who are experienced in survey research. The survey can be found at (https://research.kpchr.org/research/our-researchers/allison-naleway/dental-adolescent-immunization-study-dais). The study team planned to collect a minimum of 150 returned surveys. Surveys were mailed in November, 2015 and January, May and September of 2016 and re-mailed once to all non-responders to households with an adolescent who had a recent dental visit until a predetermined number of completed surveys were returned each quarter. A $5 gift card was offered to parents or guardians who were mailed and returned the completed survey. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at the Center for Health Research. REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) is a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies, providing an intuitive interface for validated data entry; audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures; automated export procedures for seamless data downloads to common statistical packages; and procedures for importing data from external sources.20

During the intervention period between October 2015 and September 2016, 7,327 11 to 17-year-olds had a visit in one of the eight intervention dental clinics. Of these adolescents, almost 64% (n=4,680) were due for a flu, Tdap, HPV and/or MCV4 vaccination.

Table 1 lists the number of adolescents who were eligible for the study, the number of households where surveys were sent (n=907), and the number of households who completed surveys (n=174) by sex, age and vaccinations due. Of 907 parents invited to participate, 174 (19%) completed the survey. Responders were similar to the general population of eligible participants with few exceptions. First, while 11-year-olds had more dental visits than any other age group, parents of 11-year-olds were underrepresented in the survey sampling and in returned surveys. Second, HPV was the most frequently needed vaccine at dental visits, but more surveys were mailed to and received from parents of adolescents due for the flu vaccination.

Eligible |

Adolescents whose households |

Adolescents whose |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

||

Sex |

Female |

2222 |

47 |

484 |

53 |

88 |

50 |

Male |

2458 |

53 |

423 |

47 |

86 |

50 |

|

Age in years |

11 |

1266 |

27 |

135 |

15 |

31 |

18 |

12 |

763 |

16 |

130 |

14 |

34 |

20 |

|

13 |

590 |

13 |

169 |

19 |

22 |

13 |

|

14 |

463 |

10 |

135 |

15 |

28 |

16 |

|

15 |

450 |

10 |

121 |

13 |

23 |

13 |

|

16 |

682 |

14 |

136 |

15 |

23 |

13 |

|

17 |

466 |

10 |

81 |

9 |

13 |

7 |

|

Vaccinations due |

Any Flu |

3551 |

76 |

727 |

80 |

134 |

77 |

Any HPV* |

4297 |

92 |

691 |

76 |

123 |

71 |

|

Any MCV4 |

1965 |

42 |

301 |

33 |

49 |

28 |

|

Any Tdap |

960 |

20 |

134 |

15 |

22 |

13 |

|

Table 1 Adolescents in Intervention clinics with any vaccinations due between 10/01/15 & 09/30/16

*1st, 2nd or 3rd dose.

Table 2 describes the demographic characteristics of parents who completed the survey. Most parents were women (88%), Caucasian (84%), non-Hispanic (87%), and had more than a high school education (87%). Ninety-four percent of the respondents indicated they were the parent who attended the dental visit with their child. Reported race and ethnicity were comparable to the 2016 American Community Survey where Portland Metro Area residents were reported as 85% Caucasian and 90% non-Hispanic.

n |

% |

||

Sex |

Female |

153 |

88 |

Male |

18 |

10 |

|

No response |

3 |

2 |

|

Age in years |

30-39 |

47 |

27 |

40-49 |

92 |

53 |

|

50-59 |

22 |

13 |

|

60-69 |

3 |

1 |

|

No Response |

10 |

6 |

|

Ethnicity |

Hispanic, Latino or Spanish origin |

13 |

8 |

No Response |

9 |

5 |

|

Race |

White |

147 |

84 |

Black/African American |

3 |

2 |

|

American Indian/Alaska Native |

- |

- |

|

Asian |

11 |

6 |

|

Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander |

1 |

0 |

|

Other |

6 |

4 |

|

No Response |

6 |

4 |

|

Education |

HS graduate or less |

15 |

9 |

Some college |

28 |

16 |

|

Associates degree |

25 |

14 |

|

Bachelor’s Degree |

56 |

32 |

|

Masters or PhD |

44 |

25 |

|

No Response |

6 |

4 |

|

Household income |

Less than $40,000 |

12 |

7 |

$40,000 - $59,999 |

22 |

13 |

|

$60,000-$79,999 |

25 |

14 |

|

$80,000-$99,999 |

33 |

19 |

|

$100,000-$149,000 |

51 |

29 |

|

$150,000 or more |

19 |

11 |

|

No Response |

12 |

7 |

Table 2 Demographic characteristics of accompanying parent of adolescent who visited an intervention clinic and had any vaccinations due between 10/01/15 & 09/30/16 (N=174)

When asked if they received any type of written vaccination information from a dental team member, such as a report from an electronic medical record or a brochure, 69% of respondents said they received some form of written vaccination information (data not shown). However, only 25% of respondents indicated that they received a verbal vaccine recommendation from any member of the dental team (data not shown). Of those who reported receiving a verbal recommendation, the recommendation was about three times more likely to have come from hygienists than from dentists or dental assistants.

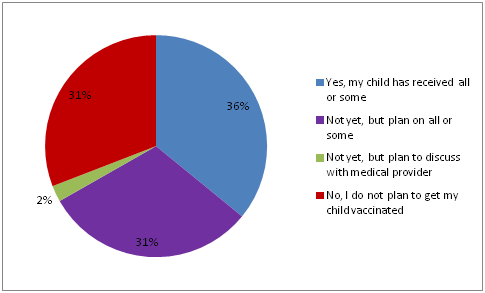

Figure 1 shows Parental comfort with dental providers making vaccine and other preventive health services recommendations and follow-up on vaccination recommendations.

Figure 1 Parental comfort with dental providers making vaccine and other preventive health services recommendations and follow-up on vaccination recommendations.

Seventy-three percent of parents indicated that they were either comfortable or neutral about dental providers making vaccine recommendations, and 74% indicated that they were comfortable or neutral about dental providers making recommendations for other preventive health services. While most respondents indicated comfort or neutrality, 27% and 26% of respondents were somewhat or very uncomfortable with dental providers recommending vaccines or other preventive health services, respectively.

Of those parents who recalled receiving specific vaccine recommendations at their child’s dental visit (n=42) over two-thirds (67%) reported that their child had received all or some of the recommended vaccines since the visit or that they were planning to obtain the vaccines. Of the 31% who did not plan to follow up, comfort with receiving a vaccine recommendation from the dental team was evenly distributed, with 38% indicating they were very to somewhat comfortable, 24% indicating they were neutral, and 38% indicating they were very or somewhat uncomfortable with dental providers making vaccination recommendations (data not shown).

Nearly two-thirds of adolescents with a dental visit during the intervention period were due for one or more adolescent vaccinations. Most parents who were recommended adolescent vaccines by dental staff indicated they were comfortable with dental providers recommending vaccines or other preventive health services, such as mammograms and blood pressure checks. Additionally, many parents who reported receiving a vaccine recommendation also reported that their child had since received the recommended vaccination or was planning to do so. However, over one quarter of parents were uncomfortable with dental provider recommendations and almost a third did not plan to have their child receive the vaccinations their dental provider recommended.

It is encouraging that most parents are comfortable or neutral about dental provider vaccine recommendations. The acceptability of dental providers making preventive care recommendations observed in the current study is consistent with parents’ acceptance of other venues for vaccination, such as school-based health centers (70%) and public health clinics (74%) and pharmacies (29%).3,12 Given there is less primary medical care utilization from childhood to early adulthood21 and many adolescents receive preventive dental care twice a year, dental visits offer a unique opportunity to recommend preventive care services such as vaccinations.

Although many parents or guardians were comfortable with receiving vaccine recommendations in the dental setting, some were not. Twenty seven percent of parents or guardians were somewhat or very uncomfortable with receiving vaccine recommendations in a dental setting, and 31% of parents who received a recommendation indicated they did not plan to obtain the vaccination for their child. A 2015 systematic review acknowledges that strategies such as knowledge and awareness raising can reduce vaccine hesitancy.22 However, the most effective interventions relied on multi-component strategies, specifically interventions that met the needs and concerns of a specific vaccine hesitant population. For example, one recent HPV vaccine specific trial in a medical setting implemented motivational interviewing along with other strategies for vaccine resistant parents and found that adolescents in the intervention group significantly increased their HPV vaccine initiation and completion.23 Additional research is needed to identify appropriate strategies to address hesitancy in a dental setting.

One limitation of the current study was the response rate. Only 19% of the invited participants returned their surveys, but the survey respondents were representative of the sampled population in terms of gender, age, and vaccinations due. Additionally, the response rate of the current study is similar to other recently published health survey response rates.24–26

The current study relied on dental teams to deliver the vaccine recommendation intervention. However, when we inquired about receipt of intervention, parents or guardians did not consistently report receiving written recommendations, and even fewer reported receiving verbal recommendations. This suggests that either the study intervention was not administered consistently, survey questions were not clear, or dental staff provided information to parents that parents later could not recall. However, even with the intervention not fully realized, most parents reported being comfortable with the idea of dental provider recommendations.

Our finding that parents are comfortable receiving vaccine recommendations from dentists coincides with recent interest in having dentists take a more prominent role in managing their patient’s total health27,28 and paves the way for vaccine discussions in the dental setting. Given the increase in HPV-associated head and neck squamous cell carcinomas,14,29,30 professional dental associations are encouraging dentists to consider adding HPV information to their patient messages.30,31 Including other adolescent vaccinations, and other preventive health services, in messaging as well is a common-sense approach from patient health and economic perspectives and may be effective at increasing rates of vaccination among adolescents and other key populations.

Recommending vaccines in alternative settings is a promising way to close vaccination gaps, and in turn to relieve burden and costs that accompany failure to vaccinate and prevent cancer. In response to the call to prioritize improving adolescent vaccination rates,3 this research is an important step in establishing the appropriateness of the dental setting for provider recommendations. More research is needed to determine how vaccination recommendations can be successfully incorporated into the dental setting, and to develop appropriate strategies for vaccine resistance across all settings.

This study was funded by a Pfizer Independent Grant for Learning & Change, Grant # 15422277. Pfizer IGLC was not involved in the design and conduct of the study; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or in the preparation, review, or approval of this manuscript.

The authors would like to thank Todd Hannon, who provided specific literature review regarding disease burden, and Weiming Hu, who provided data analysis, as well as dentists and dental staff of Permanente Dental Associates and the Kaiser Foundation Health plan, who were instrumental to conducting this research.

The authors declare there is no conflict of interest.

None.

©2019 Waiwaiole, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.