Journal of

eISSN: 2469 - 2786

Research Article Volume 5 Issue 3

1Ministry of Agriculture, Iraq

2College of Agriculture, University of Diyala, Iraq

Correspondence: Hussein Ali Salim, Ministry of Agriculture,Baqubah-Diyala-Iraq, Iraq, Tel +964707532321

Received: August 04, 2017 | Published: August 22, 2017

Citation: alim HA, Hantoosh MNK, Rashid FT, et al. The effect of alcoholic extract of Silybum marianum leaves against some of Rhizoctonia solani strains. J Bacteriol Mycol Open Access. 2017;5(3):303-305. DOI: 10.15406/jbmoa.2017.05.00136

The antifungal activity of ethanol extract of Silybum marianum was investigated in-vitro against three strains of Rhizoctonia solani at different concentrations (5, 10, 15 and 20%). Bioassay of extract was conducted by poisoned food technique with three replications. The findings showed that strain of R. solani (Eggplant) was susceptible to concentrations of S. marianum more than other strains in mycelial growth and inhibition percentage of fungal growth (3.9cm, 56.4%) respectively whereas means of concentrations resulted to reduce the fungal growth gradually with increase concentration of S. marianum (5.7, 4.4, 4.3 and 1.6cm) for concentrations of (5, 10, 15 and 20%) respectively, A concentration of 20% was recorded maximum of inhibition percentage of mycelial growth of R. solani strains 82.2% followed by concentrations of 15, 10 and 5% that recorded 52.2, 50.3 and 36.2% respectively. The interaction between concentrations of S. marianum with strains of R. solani was showed significantly differences between them in mycelial growth and inhibition percentage of fungal growth for all R. solani strains.

Keywords: silybum marianum, rhizoctonia solan, poisoned food technique

R. solani is the most widely known and most studied species of genus Rhizoctonia. It was originally described by Julius Kühn from potato in 1858.1 R. solani is soilborne Basidiomycete occurring world-wide. Its highly destructive lifestyle as a non-obligate parasite causes necrosis and damping-off on numerous host plant species. Because of the lack of conidia, R. solani exists as vegetative hyphae and sclerotia in nature. Sclerotia are an encapsulated, tight hyphal clump that protects and preserves the fungus over non-optimal times. The fungus is dispersed mainly via sclerotia, contaminated plant material or soil spread by wind, water or during agricultural practices such as tillage and seed transportation.2 Phytopathogenic fungi are controlled by synthetic fungicides; however, the use of these is increasingly restricted due to the harmful effects of pesticides on the environment.3 Continuous application of such chemicals has negative impacts on human health and destruction of the ecosystem that results in new strains of pathogens that are more resistant and difficult to control.4 It has become necessary to adopt eco-friendly approaches for better crop health and for yield. In the past, several higher plants have proved their usefulness against a number of fungi.5 Plant extracts have the ability to inhibit mycelial growth in many fungal species.6-8 Silybum marianum (L), milk thistle, is an annual or biennial herb. It belongs to the family Asteraceae.9 The plant is known for its medicinal properties having important chemical constituents including several flavonolignans collectively known as silymarin that has antioxidant properties.10 In the present study, the antifungal activity of leaves extract of S. marianum was tested in vitro against the R. solani strains that isolated from the plants (tomato, eggplant, and cauliflower).

A laboratory experiment was carried out in a college of agriculture, university of Diyala during 2016 .The S. marianum leaves were collected from orchard located in Baqubah city, R. solani strains were isolated from infected plants (tomato, eggplant and cauliflower). Leaves of S. marianum were thoroughly washed under tap water to remove dust and other impurities then dried and powdered with the help of a blender to a fine powder, 250 gm powder was soaked with 500 ml of ethanol for preparing the alcoholic extract and kept on shaker about 24 hour for continuous stirring, the extract was filtered by double layered muslin cloth and the extracts were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 minutes. Supernatant was dried by oven at 40 ̊C to evaporate the solvent and it was turned to solid. Concentrations of extract 5, 10, 15, 20 % were prepared and poured into Petri dishes by poison food technique,11 then allowed to solidify. The Petri dishes were inoculated with the pathogen by transferring five mm diameter agar disc from the fresh cultures. Three replications were maintained for each treatment. The basal medium (PDA) without any plant extract served as the control, all the inoculated Petri dishes were incubated at 25±1 ̊C for seven days. The cross diameters of colony growth of test fungus was measured in all the treatments and compared with the control. The percent inhibition of fungal growth was estimated by using following formula.12

C-T

I = ------- × 100

C

Where, I = percent inhibition, C = Colony diameter in control and T = Colony diameter in treatment.

The experiment was conducted in Factorial Experiments and the data was analyzed by one way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA).13

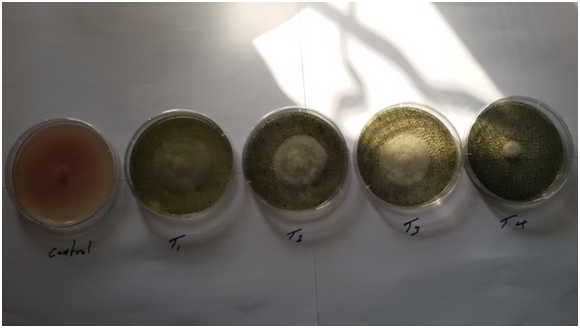

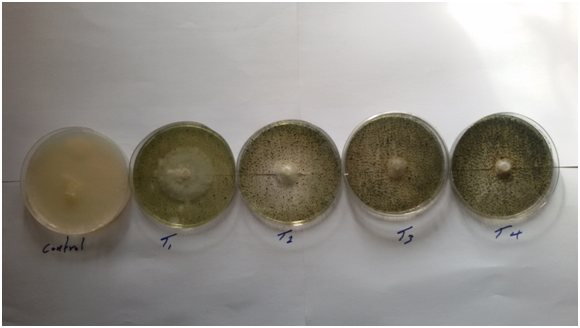

The data revealed that means of R. solani strains were significantly difference in mycelial growth of R. solani at all tested concentrations of S. marianum, R. solani (Eggplant) was susceptible to concentrations of S. marianum more than other strains (3.9 cm) whereas means of concentrationsresulted to reduce the fungal growth gradually with increase concentration of S. marianum (5.7, 4.4, 4.3 and 1.6 cm) for concentrations of (5,10,15 and 20%) respectively, interaction between concentrations of S. marianum with strains of R. solani was significantly difference in reduction of fungal growth of R. solani (Table 1 & Figures 1-3). R. solani (Eggplant) was susceptible to concentrations of S. marianum in inhibition percentage of fungal growth at (56.4%) followed by R. solani (Tomato) 43.5% and R. solani (cauliflower) 32.6%, concentrations of S. marianum showed significant activities in percent inhibition of fungal growth of R. solani . A concentration of 20% was recorded maximum of inhibition percentage of mycelial growth of R. solani strains 82.2% followed by concentrations of 15, 10 and 5% that recorded 52.2, 50.3 and 36.2% respectively. The interaction between concentrations of S. marianum with strains of R. solani was showed significantly differences between them (Table 2).

Strains of R. solani |

Concentrations of Silybum marianum |

Means of |

||||

5% |

10% |

15% |

20% |

Control |

||

R. solani (Tomato) |

5.2 |

5 |

4.9 |

1.3 |

9.0 |

5.0 |

R. solani (Eggplant) |

5.4 |

2 |

1.8 |

1.4 |

9.0 |

3.9 |

R. solani (cauliflower) |

6.6 |

6.4 |

1.8 |

2.1 |

9.0 |

6.0 |

Means of Concentrations (cm) |

5.7 |

4.4 |

4.3 |

1.6 |

9.0 |

|

Table 1 In vitroefficacy of ethanol extract of different concentrationsof S. marianum on fungal growth of R. solani strains

CD (0.05) Concentrations 0.3

CD (0.05) Strains of R. solani 0.2

CD (0.05) Concentrations × Strains of R. solani0.6

Figure 1 Efficacy of ethanol extract of different concentrationsof S. marianum on R. solani (Tomato).

Figure 2 Efficacy of ethanol extract of different concentrationsof S. marianum on R. solani (Eggplant).

S. marianum extract has antifungal effects and preventing the growth of fungi.10 S. marianum extract contains 70% silymarin, a mixture of the silibinin and flavonolignans. So these phytochemicals may also be toxic to bacterial cell and may be responsible for the antibacterial activity of S. marianum.14 S. marianum sprouts are rich in polyphenols and demonstrate antioxidative capacity.15 Plant activity of S. marianum might be due to the presence of tannins and flavonoids that acting as primary antioxidants.16 Oxidative stress induced by pathogen infection is sensed by plants in the form of activation of reactive oxygen species which subsequently activates plant defenses.17,18

Strains of R. solani |

Concentrations of Silybum marianum |

Means of |

||||

5% |

10% |

15% |

20% |

Control |

||

R. solani (Tomato) |

42.2 |

44.4 |

45.5 |

85.5 |

0 |

5.0 |

R. solani (Eggplant) |

40 |

77.7 |

80 |

84.4 |

0 |

3.9 |

R. solani (cauliflower) |

26.6 |

28.8 |

31.1 |

76.6 |

0 |

32.6 |

Means of Concentrations % |

36.2 |

50.3 |

52.2 |

82.2 |

0 |

|

Table 2 In vitroefficacy of ethanol extract of different concentrationsof S. marianum in percent inhibition of fungal growth of R. solani strains

Rate of inhibition

CD (0.05) Concentrations 0.9

CD (0.05) Strains of R. solani 0.7

CD (0.05) Concentrations × Strains of R. solani1.6

Under in vitro conditions, the strains of R. solani were well controlled by ethanol extract of S. marianum by different concentrations. This extract showed maximum activity; even at very low concentrations. The extract of S. marianum could be considered as potential source of antifungal compound for treating R. solani strains. We conclude from that this extract exhibit fungicidal properties that support their use as antiseptics. These need to be further evaluated under in vivo conditions so as to make minimum use of chemicals.

None.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

©2017 alim, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.