Journal of

eISSN: 2469 - 2786

Research Article Volume 13 Issue 2

Amity Institute of Biotechnology, Amity University, India

Correspondence: Dr. Kirti Rani, Associate Professor, Amity Institute of Biotechnology, Amity University Uttar Pradesh, Noida, Sec-125, Gautam Buddha Nagar, Noida-201313 (UP), India

Received: July 22, 2025 | Published: August 14, 2025

Citation: Rani K. Immobilization of Vigna mungo amylase onto chemically modified woven cotton fabric: a cost effective and sustainable enzyme engineering approach. J Bacteriol Mycol Open Access. 2025;13(2):123-127. DOI: 10.15406/jbmoa.2025.13.00411

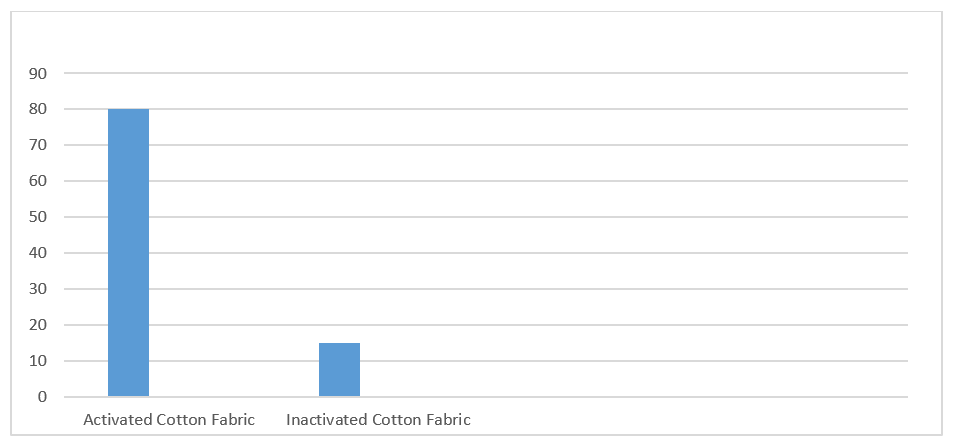

Plant based amylases are affordable and sustainable alternative which are exploited these days to get immobilized by adsorption, entrapment, covalent attachment, and cross-linking. Amylases is well known thermostable enzyme (stable at 80-90°C) to economize various industrial processes like, leather, paper, wood, detergent, refinery, distillery and starch industries. Thermostable enzymes isolated from thermophilic organisms have found several commercial applications because of their overall inherent stability. Improved, cost effective and green method of enzyme immobilization was developed to immobilize Vigna mungo amylase onto activated cotton fabric with ease. 80% Retention of immobilized Vigna mungo Amylase was achieved onto woven activated cotton fabric (80%) when compared to inactivated woven cotton fabric (15%). Various Kinetic parameters were studied for free and immobilized enzyme for finding its improved stability on varying pH, time of incubation, temperature, CaCl2 Concentration. So, that immobilized amylase would further propose for various industrial applications like food, chemical, textiles and paper industries and used for various chemical/biological conversions for synthesising novel materials when found better for its improved kinetic parameters with free amylase.

Keywords: amylase, immobilization, Vigna mungo amylase, cotton fabric

Amylases are widely used ubiquitous enzymes which synthesised by plants, animals and microbe and have prominent metabolic role in carbohydrate metabolism.1-3 The increased industrial use of enzymes have increasing demand globally of about US $ 3 billion. Hence, amylase are most widely used industrial enzyme among all enzymes which grabbed 65% of the world enzyme market niche.4-6 Amylases were well known to be used in food, paper, detergent, fermentation, textile, pharmaceutical, leather and chemical industries. Amylases are extracellular enzymes which known for breakdown of α-1,4 glycosidic bonds between adjacent glucose molecules of linear amylose chain of starch.7-9 Hence, amylases have significant role in brewing, liquefaction, saccharification, bio-fuel production, fabric desizing and processing of starch because of their overall inherent heat stability. Improved, cost effective and green method of enzyme immobilization was developed to immobilize Vigna mungo amylase onto activated cotton fabric with ease.10-12 Previously, enzyme bound egg albumin nanoparticles (EANPs) was prepared by toluene driven modified emulso-desolvation method at nanoscale. The study confirmed that desolvation method was affordable and non-toxic green method as compared to other previously reported methods.12-16 Amylase have been found to be very excellent enzyme in fabric desizing and washing as compared to other harsh chemicals treatments like sulphate/alkali/bromide during processing.17-20 Immobilized analyses have advantages over free enzymes in terms of convenient handling of the enzyme, easy separation from the product, eliminating protein contamination of the product and potent recovery with improved reusability of immobilized enzyme.21-26 Hence, immobilization of amylases on to chemically active woven cotton fabric is good cost-effective, non-corrosive and sustainable approach due to having good thermal stability, eco-friendly and less labour requirement to achieve more effective immobilization results.27,28

Methodology: One of the variety of pulse called black gram or urad bean (Vigna mungo) was purchased from a local market in NCR-New Delhi, India. Grains were surface sterilized with 0.5% sodium hypochlorite solution washed several times and soaked in distilled water for 24h.23,24

Preparation of crude extract: 20 gm sprouted Vigna mungo) were homogenized at 0-4°C in 0.05M potassium phosphate buffer (pH-7) and centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 15 minutes. Supernatant was collected as crude alkaline phosphatase and stored at 4°C.25,26

Determination of amylase activity by DNS method: The activity of extracellular amylase was estimated by determining the amount of reducing sugars released from starch. The sugars were quantified by the method of 3,5-dinitrosalicylicacid (DNS), according to Miller (1959). The starch solution was prepared from 1% (w/v) soluble starch in distilled water. Volumes of 0.5 ml of the enzymatic extract were added to 1 ml of the starch solution and the mixture incubated at 37ºC for 15 min. After that 2 ml of DNS was added to terminate the reaction and the reaction mixture was boiled at 100ºC for 5 minutes. The amount of reducing sugars in the final mixture was determined spectrophotometrically at 570 nm. One unit of enzymatic activity is defined as the amount of enzyme that produces 1µmol/min of maltose.23-26

Characterization of free and immobilized amylase

Optimum pH for amylase activity

The effect of pH on the amylase activity was measured at different pH values. The pH was adjusted using the following buffers: sodium acetate (pH 2.5-6.5), sodium-phosphate (pH 7.0-8.0), and sodium carbonate (pH 8.5.0-10.5). 0.5 ml amylase and 1 ml of 1% starch solution was incubated at 37ºC for 20 min along with 0.5 ml of buffer for each pH. The reaction was terminated by adding 2 ml dinitrosalicylic acid reagent, followed by heating in boiling water bath for 5min. This was followed by addition of 1 ml sodium potassium tartarate (40 %). The reaction mixture was cooled and diluted with5ml of water and the absorbance at 570 nm was monitored. The activity of the enzyme was then measured.25-28

Optimum temperature for amylase activity

Amylase activities were determined at a temperature range of 20-70°C (with an interval of 10°C) with 1% soluble starch as substrate. The relative activity at different temperatures was calculated, taking the maximum activity obtained as 100%. The effect of temperature on enzyme activity was measured by incubating the purified enzyme at temperature range of 20- 70°C for 15 min. After heat treatment the enzyme solution was cooled, and the relative activities were measured under standard assay conditions.25-28

Effect of CaCl2 concentration on amylase activity

The effect of CaCl2 on activity of the enzyme was studied by performing the enzyme assay at different CaCl2 concentrations (2%-8%), the optimum enzyme activity was determined by incubating the enzyme with buffer described above for 15 minutes and then carried out the enzyme activity by the standard curve of maltose.25-28

Effect of substrate concentration on amylase activity

Optimal substrate concentration needed for enzyme activity was estimated by incubating the reaction mixture for 15 minutes at different concentrations of starch solution (0.5% - 2%). The optimum substrate concentration of enzyme was determined by incubating the enzyme solution at different concentrations in the range of 0.5% - 2% for 15 minutes and estimating the enzyme activity by the standard curve of maltose.25-28

Effect of incubation time on amylase activity

The effect of time of incubation on the activity of the enzyme was studied by performing the enzyme assay at different time (5min-25min), with an interval of 5 min. The optimum time of incubation was determined by incubating the enzyme with the buffer at different time intervals and then carrying out the enzyme activity by the standard curve of maltose.25-28

Immobilized amylase Vigna mungo on activated woven cotton fabric

Equal sized (10-15cm) of woven cotton fabrics were taken and washed with double distilled water. These fabrics were then dipped in bath of 0.01 ml of sodium periodate for its oxidation at 40°C and pH 6.0 for 8 hours in a bath and further subjected for activation with the treatment of 2 ml of 2-3% NaCl along with 10mg sodium nitrate for half hour. The fabric pieces were occasionally stirred with glass rod. The fabric pieces were then removed with forceps and washed with 0.1M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7). Activated fabric pieces were then dipped in 3-5 ml of the 10% glutaraldehyde solution and incubated at 37˚C for 1 hour. The incubated fabric was then washed with double distilled water for 4-5 hours for every 30 minutes. Crude extract of Vigna mungo amylase was taken for immobilization and the activated fabrics were then dipped in the 10 to 15 ml of crude extract in a petridish. The petridish was then incubated at 37˚C for 24 hours. The fabric pieces were then washed with 1M KCl for 2 hours at 37˚C. (Figure 1).27-28

% retention of the immobilized enzyme was then calculated as follows:

Percent (%) of immobilization

80% Retention of immobilized Vigna mungo Amylase was done onto woven activated cotton fabric when compared to inactivated woven cotton fabric where only 15% of amylase immobilization found (Figure 1). Results of present proposed work were found to comparable with previous fabric-based enzyme immobilization methods respectively; of upto 82% of Phaseolus vulgaris amylase immobilization,27 92% of Vigana radiata amylase immobilization28 and upto 80% of Vigna mungo amylase immobilization29.

Figure 1 Comparative % of immobilization retention of Vigna mungo amylase on to activated and inactivated cotton fabric.

Comparative kinetic parameter studies of free and immobilized enzyme (Table 1)

|

Kinetic parameters |

Free Vigna mungo amylase |

Immobilized Vigna mungo amylase on to activated woven cotton fabric |

|

Optimum pH |

5.0 |

5.5 |

|

Optimum temperature |

45 degree C |

50 degree C |

|

Effect of CaCl2 concentration |

6% |

Nil effect |

|

Effect of substrate concentration or substrate saturation effect |

1% |

1.25% |

|

Time of incubation optima |

20 minutes |

10 minutes |

Table 1 Comparative studied various kinetic parameters for free and immobilized Vigna mungo amylase

pH optima

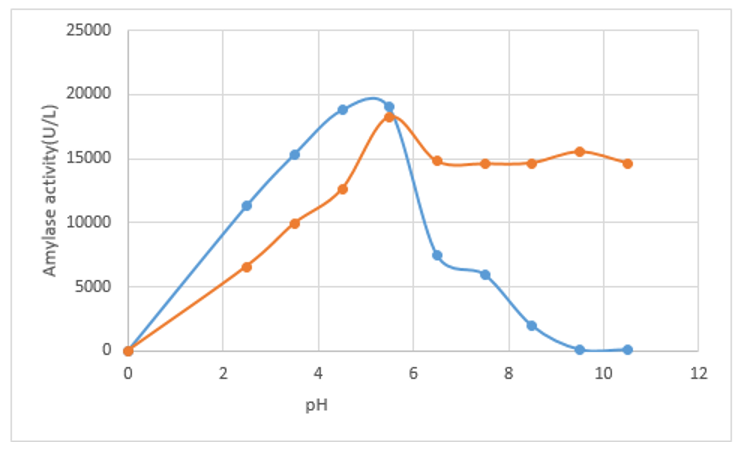

The pH optimum for Amylase activity was determined using buffers ranging in their pH values from 2.5-10.5. Soluble starch was used as substrate to determine the activity of amylase. From the results obtained it was revealed that the immobilized Vigna mungo exhibited high activity at pH 5.5 as compared to free enzyme (pH 5) when stability was tested after incubation for 20 minutes at different pH solutions (Figure 2). The immobilized enzyme was found to be stable in the pH range of 4.0-7.5 which were found to comparable with previous observations in pH range of 5.0 to 7.0.28-32

Figure 2 Comparative pH optima study on immobilized (Blue virgule) and free amylase (Red virgule) activity of Vigna mungo amylase.

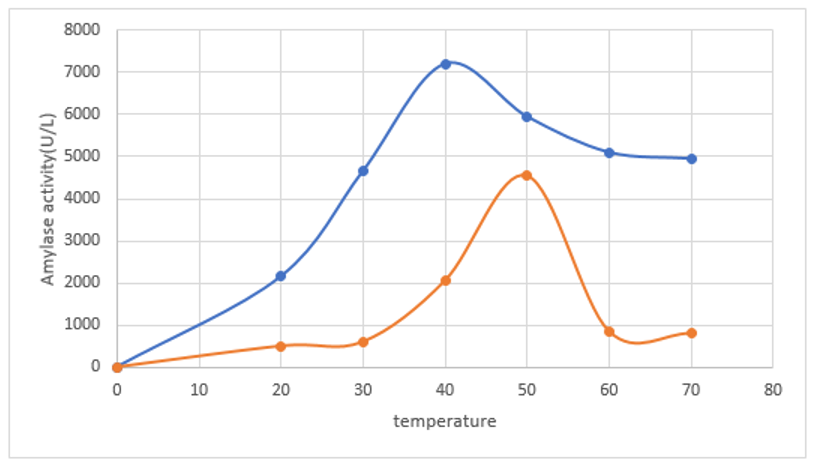

Temperature optima

Immobilized Vigna mungo Amylase exhibited maximum activity after 15 min incubation at 50°C while the free enzyme has exhibited 45˚C. Hence, observed thermal stability of free and immobilized Amylase was found almost same with only difference of 5 degree on varied temperature range of 20-60°C (Figure 3). Free and immobilized amylases were found to be stable up to 65°C and 70°C respectively for 20 minutes incubation which are very much found comparable with previous findings of pulses amylases immobilization methods.33-36

Figure 3 Comparative temperature optima study on immobilized (Blue virgule) and free amylase (Red virgule) activity of Vigna mungo amylase.

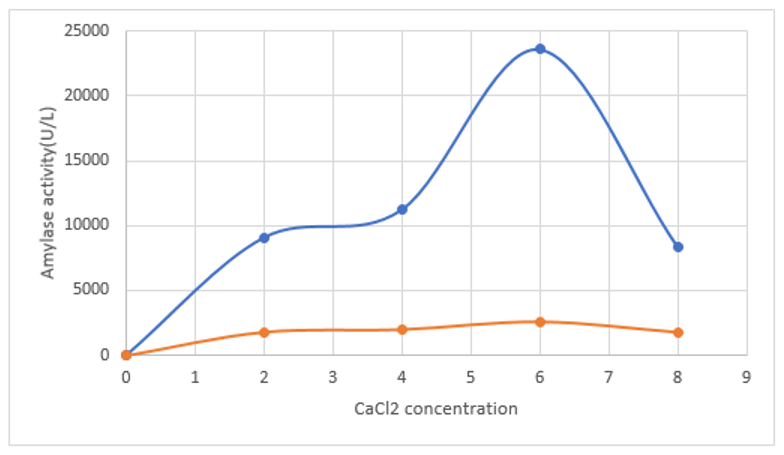

Effect of CaCl2 concentration

The reaction mixture of free and immobilized Amylase was incubated for varied CaCl2 concentration for testing their calcium- metalloenzymes properties. It was confirmed that 6% CaCl2 concentration, immobilized enzyme showed maximum activity due to increasing amylase activity due to Ca2+ ions presence when compared to free enzyme (no effect of CaCl2). It has ability to interact with negatively charged amino acid residues such as aspartic and glutamic acids of enzyme, which resulted in stabilization as well as maintenance of enzyme conformation after immobilization (Figure 4). These observations of present design of Vigna mungo amylase immobilization are found to same as observed in previous reports of pulses amylase immobilization protocols.37-39

Figure 4 Comparative study of effect of CaCl2 concentration on immobilized (Blue lined) and free amylase (Red lined) activity of Vigna mungo amylase.

Effect of substrate concentration

Effect of substrate concentration was studied for free and Immobilized Vigna mungo amylase and increased above 0.1%, rate of reaction was found that increased progressively up to 1.5% for both, free and immobilized enzymes. When concentration increased above 1.5%, the rate of reaction remained almost constant. The optimum substrate concentration or substrate saturation for free Vigna mungo amylase was found at 1% while the optimum substrate concentration for free Vigna mungo amylase was found up to 1.25% (Figure 5). These results of studied substrate concentrations of immobilized amylase are found to notably similar with earlier findings based on respective pulses amylase immobilizations methods.40,41

Effect of incubation time

The reaction mixture of amylase was incubated for varied time intervals from 5 to 25 minutes. Optimum time of incubation of free amylase and immobilized amylase was found 20 minutes and 10 minutes respectively. Hence, Immobilized amylase has lesser time of incubation for maximum enzyme activity as compared to free enzyme (Figure 6). These results are found to have notable similarity with previously proposed pulses amylase immobilization methods.40,41

From the above results, this designed study came to conclusion that the optimum pH for free Vigna mungo amylase and immobilized was 5 and 5.5 respectively. The observed optimum temperature of free and immobilized amylase was in the range of 40˚C-50˚C whose result are comparable with previous results, and it was improved upon immobilization. Observed optimum CaCl2 concentration of the free amylase enzyme was 6% and nil after immobilization whose observation comparable with previous findings and found to be improved after immobilization. Hence, amylase activity of Ca2+ ions enhancement is based on its ability to interact with negatively charged amino acid residues such as aspartic and glutamic acids, which resulted in stabilization as well as maintenance of enzyme conformation. The optimum substrate concentration of the free amylase was 1% and the optimum substrate concentration of immobilized enzyme came out to be 1.25% which was good and comparable same as in previous studied observations. The optimum time of incubation of free pulse amylase was found to 20 minutes and immobilization amylase, it was 10 minutes which was good so that, less time needed for immobilized enzyme to form products in reaction systems. These results were found to comparable good as confirmed in previous designed immobilization studies (Table 1).28-43

It was concluded from this designed fabric mediated amylase immobilization study that immobilization results showed good binding affinity and storage stability of the Vigna mungo amylase up to 80% after immobilization which can further exploited to get used in food, textiles and Pharma industries for achieving better reusability and preservation longevity up to 5 months at 4 degree C. Vigna mungo amylase was found cost-effective, green and sustainable plant sources for extracting amylase for immobilization methods in various enzyme-based industries. Designed studies also confirmed that optimum pH for Amylase extracted from Vigna mungo was 5.5 which can be considered good to choose Vigna mungo immobilized amylase in many chemical industries. Observed optimum temperature of the Vigna mungo immobilized amylase falls in the range of 40˚C-50˚C that will be good choice for researchers to exploit this affordable amylase in distillery, refinery, paper, leather, garment and detergent industries.27,28,39,43 Immobilization of enzyme on cotton fabric might be further considered a green, cost effective and sustainable choice whose chemical modification and electrochemical activation will be done with ease by doping with compatible nanoparticles and other electrochemical active agents.46,47 Hence, further these cotton fabric based enzyme immobilization can be helpful to design and manufacture various single electrode-based biosensors and medical devices.

I would like to express my cordial appreciation to Amity University Uttar Pradesh, Noida (India).

The author declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

©2025 Rani. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.