Journal of

eISSN: 2469 - 2786

Research Article Volume 13 Issue 2

1Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Sana’a University, Yemen

2Laboratory Department, Faculty of Medical Sciences, the National University, Yemen

Correspondence: nas F Al-Awadhi, Microbiology Branch, Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Sana’a University, Sana’a, Yemen

Received: July 31, 2025 | Published: August 19, 2025

Citation: Al-Awadhi EF, Al-Arnoot S, Ali AA, et al. Antimicrobial efficacy of aqueous and ether extracts of clove (Syzygium aromaticum) against clinically significant gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria. J Bacteriol Mycol Open Access. 2025;13(2):129-133. DOI: 10.15406/jbmoa.2025.13.00412

The rise of antimicrobial resistance has driven the search for alternative therapeutic agents, particularly from natural sources. Syzygium aromaticum (clove) is known for its antimicrobial properties, and this study aimed to evaluate the antibacterial efficacy of its aqueous and ether extracts against clinically significant Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria, including Escherichia coli, Klebsiella spp., Pseudomonas spp., Proteus spp., Salmonella spp., Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus saprophyticus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, and Streptococcus pyogenes. The antibacterial activity was assessed using the agar diffusion method at concentrations of 25%, 50%, and 100%. The results showed that both extracts exhibited antibacterial activity, with the aqueous extract generally being more effective. Among Gram-negative bacteria, Salmonella spp. showed the highest susceptibility to the aqueous extract (19.6 mm at 100%), while Proteus spp. exhibited the highest inhibition by the ether extract (17.0 mm at 25%). For Gram-positive bacteria, S. epidermidis was the most sensitive, with a 24.0 mm inhibition zone at 100% of the aqueous extract. The ether extract showed lower antimicrobial activity across all tested bacteria. These findings suggest that clove extracts, particularly the aqueous extract, possess significant antibacterial potential and may serve as alternative antimicrobial agents. Further studies are recommended to explore the phytochemical components and mechanisms of action responsible for this activity.

Keywords: Syzygium aromaticum, clove extract, antibacterial activity, antimicrobial resistance, natural antimicrobials, aqueous extract, ether extract, clinical bacterial isolates

Infectious diseases remain a major global health concern, contributing significantly to morbidity and mortality across both developed and developing countries.1 In tropical and low-resource regions, they account for nearly half of all deaths, with bacterial infections being particularly prevalent.2 The advent of antibiotics in the 20th century revolutionized the treatment of bacterial infections. However, the rise of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) has dramatically reduced the effectiveness of many of these life-saving drugs. The misuse and overuse of antibiotics, poor adherence to treatment regimens, and the natural genetic adaptability of bacteria through horizontal gene transfer have all contributed to the emergence and spread of resistant pathogens.3

This crisis is especially acute in low-resource settings such as Yemen, where protracted conflict and the collapse of healthcare infrastructure have fueled the spread of infectious diseases.4-6 Limited access to quality healthcare services, inadequate sanitation, and escalating antimicrobial resistance further complicate disease control efforts.7 Several studies have reported elevated prevalence rates of infectious diseases among high-risk populations. For example, Helicobacter pylori infections have been found to be significantly more common among patients with type 2 diabetes,8 while viral infections are frequently detected among pregnant women.9-11 These high prevalence rates are often driven by a lack of awareness regarding transmission pathways and preventive strategies,12 combined with a shortage of diagnostic capabilities. In many cases, outdated serological methods are still in use, while access to modern molecular techniques such as PCR remains limited due to financial and logistical constraints.13,14

In light of these challenges, the exploration of natural alternatives to synthetic antimicrobials has gained renewed interest. Medicinal plants represent a rich source of bioactive compounds with known antimicrobial properties. Plant-derived essential oils and secondary metabolites have long been utilized in traditional medicine, food preservation, and pharmaceutical applications due to their antibacterial, antifungal, and antiviral activities.15-17

Clove (Syzygium aromaticum), a widely used spice in traditional medicine, has attracted significant attention for its broad-spectrum antimicrobial potential. Its flower buds contain a variety of bioactive compounds, most notably eugenol, which exhibits antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant properties.18 Clove extracts have been historically applied in the treatment of ailments such as toothaches, digestive problems, respiratory infections, and parasitic diseases.19,20

Given the urgency to identify alternative antimicrobial therapies amid growing AMR, this study aims to evaluate the antibacterial efficacy of aqueous and ether extracts of clove against selected clinical bacterial isolates. Investigating the antimicrobial potential of these extracts may provide valuable insights for the development of novel, plant-based therapeutic agents, particularly in settings with limited access to conventional antibiotics.

Bacterial isolates

The bacterial isolates utilized in this study were sourced from clinical samples of patients suffering from a variety of infections, including wound infections, sore throat, urinary tract infections, gastrointestinal infections, vaginal infections, and skin infections. The isolates encompassed both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria. The Gram-negative bacterial isolates included Escherichia coli, Klebsiella spp., Pseudomonas spp., Proteus spp., and Salmonella spp. These bacteria were selected due to their clinical significance in causing urinary tract infections, gastrointestinal disorders, and wound infections.21

The Gram-positive bacterial isolates comprised Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus saprophyticus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, and Streptococcus pyogenes. These pathogens are well-documented as being associated with skin infections, respiratory infections, and various healthcare-associated infections.22 All bacterial isolates were preserved in glycerol stocks at -20°C prior to use. To prepare for testing, the isolates were reactivated by culturing them in nutrient agar and incubating at 37°C for 24 hours. The bacterial suspensions were then standardized to 10⁶ CFU/ml using sterile saline, aligning with the 0.5 McFarland standard to ensure consistency in antimicrobial susceptibility testing.23

Dried clove buds (Syzygium aromaticum) were procured from a local market in Ibb City, Yemen. The plant material was thoroughly cleaned to eliminate any impurities and subsequently ground into a fine powder using an electric grinder. Two types of extracts were prepared: aqueous and ether extracts, employing standard extraction methods.24

For the aqueous extract, 50g of clove powder was immersed in 500 ml of distilled water and heated to 60°C for 2 hours while continuously stirring. After cooling to room temperature, the mixture was filtered through Whatman No. 1 filter paper. The filtrate was then concentrated using a rotary evaporator at 40°C to yield a crude extract, which was stored at 4°C until further use.25 In the case of the ether extract, 50g of clove powder was macerated in 500 ml of diethyl ether for 72 hours at room temperature, with occasional shaking. The extract was filtered, and the solvent was evaporated using a rotary evaporator at 40°C, resulting in a concentrated crude extract, which was also stored at 4°C for subsequent testing.26

Three distinct concentrations of each extract were prepared: 25%, 50%, and 100%. These concentrations were achieved by dissolving the requisite amount of each crude extract in 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), which served as the negative control. The final solutions were thoroughly vortexed to ensure homogeneity before being utilized in antibacterial susceptibility testing.27

The bacterial isolates were reactivated by inoculating them into sterile nutrient broth and incubating at 37°C for 24 hours. Following this incubation, the bacterial cultures were adjusted to a standard inoculum concentration of 10⁶ CFU/ml using sterile saline, corresponding to the 0.5 McFarland standard. The bacterial suspensions were vortexed to achieve uniform distribution prior to their application in the antibacterial assay.28

The antibacterial activity of the aqueous and ether extracts of clove was evaluated using the agar diffusion method. Mueller-Hinton Agar (HiMedia) plates were prepared and allowed to solidify under sterile conditions. One hundred microliters (100 µl) of each bacterial suspension (10⁶ CFU/ml, corresponding to the 0.5 McFarland standard) was evenly spread onto the surface of sterile Mueller-Hinton Agar plates using a sterile cotton swab to ensure uniform bacterial growth.29

Wells of 6 mm in diameter were punched into the agar using a sterile cork borer, and 50 µl of each extract concentration (25%, 50%, and 100%) was carefully dispensed into the respective wells using a micropipette. The plates were allowed to stand undisturbed for 30 minutes to facilitate the diffusion of the extracts before being incubated at 37°C for 24 hours.30 A negative control (10% DMSO) was included in each plate to confirm that the solvent had no antibacterial effect. The antimicrobial activity of the extracts was assessed by measuring the diameter of the inhibition zones (in millimeters) around each well using a digital caliper. The experiment was conducted in triplicate to ensure the reliability of the results.31

This section presents the findings of the study, which investigated the antimicrobial efficacy of aqueous and ether extracts of Syzygium aromaticum (clove) against selected clinical bacterial isolates. The results are provided in tables summarizing the inhibition zone diameters (mm) for both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria at different extract concentrations (25%, 50%, and 100%). Additionally, photographic evidence illustrates the inhibition zones formed against specific microorganisms, further supporting the antimicrobial potential of clove extracts.

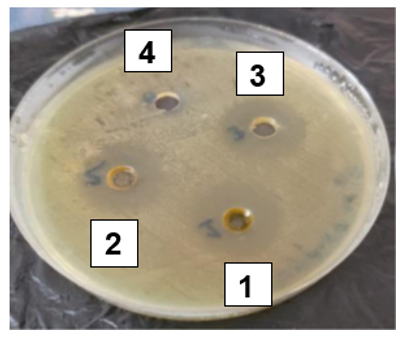

The antibacterial activity of clove extracts against Gram-negative bacterial isolates is shown in Table 1. The tested bacteria included Escherichia coli, Klebsiella spp., Pseudomonas spp., Proteus spp., and Salmonella spp. The results indicate that the aqueous extract exhibited a dose-dependent effect, with inhibition zones increasing as the extract concentration increased. Among the Gram-negative isolates, Salmonella spp. showed the highest susceptibility, with an inhibition zone of 19.6 mm at a 100% concentration, whereas E. coli exhibited moderate sensitivity with an inhibition zone of 14.6 mm at the same concentration. The ether extract also demonstrated antibacterial activity; however, its effect varied among the bacterial species. Proteus spp. exhibited the highest inhibition at a 25% concentration, forming a 17 mm inhibition zone Figure 1, whereas Pseudomonas spp. showed relatively lower inhibition at higher concentrations. These variations suggest that the extraction method and bacterial species influence the antimicrobial effectiveness of clove extracts.

|

Bacterial isolate |

Aqueous extract (inhibition zone in mm) |

Ether extract (inhibition zone in mm) |

||||

|

Concentration (%) |

25% |

50% |

100% |

25% |

50% |

100% |

|

Escherichia coli |

6.2 |

9.6 |

14.6 |

12.2 |

12.8 |

11.8 |

|

Klebsiella spp. |

6.5 |

9.0 |

14.0 |

11.0 |

10.0 |

11.5 |

|

Pseudomonas spp. |

8.3 |

12.3 |

16.6 |

11.3 |

11.6 |

9.6 |

|

Proteus spp. |

7.0 |

10.0 |

14.0 |

17.0 |

16.0 |

15.0 |

|

Salmonella spp. |

9.4 |

13.4 |

19.6 |

16.8 |

15.6 |

15.0 |

Table 1 Effect of clove extract (Syzygium aromaticum) on gram-negative isolates

Figure 1 Inhibition zones produced by ether clove (Syzygium aromaticum) extract (wells 1–3: 25%, 50%, and 100% concentrations, respectively) and negative control (well 4: 10% DMSO) against Proteus spp. on Mueller–Hinton agar.

Table 2 presents the antibacterial effects of clove extracts against Gram-positive bacterial isolates, including Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus saprophyticus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, and Streptococcus pyogenes. Similar to the Gram-negative isolates, the aqueous extract exhibited greater antibacterial activity compared to the ether extract. Among the Gram-positive bacteria, S. epidermidis Figure 2 was the most susceptible, with a maximum inhibition zone of 24 mm at a 100% concentration of the aqueous extract. In contrast, Streptococcus pyogenes exhibited the least inhibition, with an inhibition zone of 12.6 mm at 100%. The ether extract displayed a less pronounced antibacterial effect, with S. saprophyticus showing relatively stronger inhibition at lower concentrations compared to other Gram-positive isolates. These findings highlight the stronger antimicrobial potential of the aqueous extract, possibly due to better solubility of active compounds in water or enhanced diffusion in agar-based media.

|

Bacterial isolate |

Aqueous extract (inhibition zone in mm) |

Ether extract (inhibition zone in mm) |

||||

|

Concentration (%) |

25% |

50% |

100% |

25% |

50% |

100% |

|

Staphylococcus aureus |

7.0 |

11.0 |

16.2 |

9.2 |

9.1 |

9.2 |

|

Staphylococcus saprophyticus |

9.0 |

14.0 |

16.0 |

15.0 |

9.0 |

10.0 |

|

Staphylococcus epidermidis |

10.0 |

14.0 |

24.0 |

4.0 |

5.0 |

6.0 |

|

Streptococcus pyogenes |

7.2 |

9.4 |

12.6 |

8.2 |

9.4 |

10.4 |

Table 2 Effect of clove extract (Syzygium aromaticum) on gram-positive isolates

The present study investigates the antibacterial effects of clove extracts (Syzygium aromaticum) on various Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacterial isolates, as summarized in Tables 1 & 2. The results demonstrate that both aqueous and ether extracts of clove exhibit significant antibacterial activity against the tested bacterial strains. Notably, the Gram-negative bacteria, including Escherichia coli, Klebsiella spp., Pseudomonas spp., Proteus spp., and Salmonella spp., showed varying degrees of susceptibility to the clove extracts, with the highest inhibition zones observed at 100% concentration. For instance, E. coli exhibited a maximum inhibition zone of 14.6 mm with the aqueous extract and 12.2 mm with the ether extract at 100% concentration. Similarly, Salmonella spp. showed a notable inhibition zone of 19.6 mm with the aqueous extract at the same concentration. These findings align with previous studies that have reported the antibacterial properties of clove extracts against various pathogens.32,33

The results also indicate that Gram-positive bacteria, including Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus saprophyticus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, and Streptococcus pyogenes, were affected by clove extracts, albeit with varying effectiveness. For example, S. aureus showed an inhibition zone of 16.2 mm with the aqueous extract at 100% concentration, while S. epidermidis exhibited a significantly larger inhibition zone of 24 mm with the same extract. This observation is consistent with the findings of Rashad, who noted that clove extract was effective against Streptococcus species, demonstrating its potential as an antimicrobial agent.33

The differential susceptibility of Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria to clove extracts can be attributed to the structural differences in their cell walls. Gram-negative bacteria possess an outer membrane rich in lipopolysaccharides, which can act as a barrier to many antimicrobial agents, thereby reducing their susceptibility.34,35 In contrast, the simpler structure of Gram-positive bacteria, characterized by a thicker peptidoglycan layer, may facilitate the penetration of antimicrobial compounds, resulting in greater sensitivity to clove extracts.36,37 This is further supported by the findings of Kwansa–Bentum et al.,34 who reported that Gram-positive bacteria are generally more susceptible to plant extracts compared to Gram-negative bacteria.

The presence of bioactive compounds in clove, such as eugenol, has been identified as a key factor contributing to its antibacterial activity. Eugenol is known for its ability to disrupt bacterial cell membranes and inhibit metabolic processes.32,38 The current study's results corroborate previous research indicating that the phenolic compounds in clove extracts play a significant role in their antimicrobial properties.32,39 The varying concentrations of clove extracts used in this study further emphasize the importance of dosage in achieving effective antibacterial outcomes, as higher concentrations consistently yielded larger inhibition zones.

Moreover, the results suggest that the aqueous extract of clove may be more effective against certain bacterial strains compared to the ether extract. For instance, the aqueous extract produced larger inhibition zones for most Gram-negative isolates, particularly Salmonella spp. and E. coli. This finding is consistent with the work of Ahmed et al.,32 who highlighted the superior antibacterial activity of aqueous extracts of clove in their studies. The solubility of active compounds in water may enhance their bioavailability and efficacy against bacterial pathogens.

In addition to the antibacterial effects, the study also highlights the potential of clove extracts as natural preservatives in food and pharmaceutical applications. The increasing resistance of bacteria to conventional antibiotics necessitates the exploration of alternative antimicrobial agents derived from natural sources.40 Clove extracts, with their broad-spectrum antibacterial properties, could serve as effective alternatives in combating bacterial infections, particularly in the context of rising antibiotic resistance.

In conclusion, the findings of this study underscore the significant antibacterial activity of clove extracts against both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria. The results not only contribute to the existing body of knowledge regarding the antimicrobial properties of clove but also suggest potential applications in food preservation and therapeutic interventions. Future research should focus on elucidating the specific mechanisms of action of clove extracts and exploring their efficacy in clinical settings, as well as their potential synergistic effects when combined with conventional antibiotics.

The approval to conduct this research was obtained from the Ethics Committee at the College of Medical Sciences of the National University.

This work received no specific grant from any funding agency

Enas F. Al-Awadhi, Amat Alahman Ali, Bashair Al-amri, Manal Al-Rimi, Manar Al-Duais, Shema Al-Zubair: conceptualization, data curation, writing – original draft, writing – review & editing.

Enas F. Al-Awadhi, Saad Al-Arnoot: writing – original draft, writing – review & editing.

Enas F. Al-Awadhi, Amat Alahman Ali, Bashair Al-amri, Manal Al-Rimi, Manar Al-Duais, Shema Al-Zubair: writing – original draft, writing – review & editing.

The authors are grateful to the Laboratory Department, Faculty of Medical Sciences, and the National University for supporting this research

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

©2025 Al-Awadhi, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.