Journal of

eISSN: 2473-0831

Research Article Volume 7 Issue 3

Correspondence: Feriel Bouhjar, Institut de Disseny i Fabricaci, Tel 21622681792

Received: April 16, 2018 | Published: June 8, 2018

Citation: Bouhjar F, Marí B, Bessaïs B. Hydrothermal fabrication and characterization of ZnO/Fe2O3 heterojunction devices for hydrogen production. J Anal Pharm Res. 2018;7(3):315-321 DOI: 10.15406/japlr.2018.07.00246

ZnO/Fe2O3 heterojunction were prepared by sequentially depositing iron oxide α-Fe2O3 and zinc oxide ZnO films on FTO (SnO2:F) substrates. The α-Fe2O3 and ZnO films and the α-Fe2O3/ZnO heterojunction were characterized by Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FESEM), Energy-Dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX), and X-Ray Diffraction (XRD). Pure crystalline ZnO films were hydrothermally deposited on α-Fe2O3 films and the process parameters were as follows: hydrothermal time, 4h; temperature 150°C. Finally, the device was transferred to an electric oven and heated at a constant temperature of 90°C for 5h, to develop the ZnO nanostructure. The photocurrent measurements showed an increase of the intrinsic surface states or defects at the α-Fe2O3/ZnO interface. The photoelectrochemical performance of the α-Fe2O3/ZnO heterojunction was examined by chronoamperometry and linear sweep voltammeter techniques. It was found that the α-Fe2O3/ZnO structure exhibits a higher photoelectrochemical activity when compared to α-Fe2O3 thin films. The highest photocurrent density was obtained for α-Fe2O3/ZnO films in 1 M NaOH electrolyte. This high photoactivity was attributed to the high active surface area and to the external applied bias, which favors the transfer and the separation of the photogenerated charge carriers in α-Fe2O3/ZnO heterojunction devices.

Keywords: α-Fe2O3/ZnO, interface, hydrothermal deposition, heterojunction, photocurrent, mott-schottky

In recent years, a great deal of attention has been paid to heterogeneous thin film deposition on highly structured semiconductor substrates such as Fe2O3, ZnO, TiO2, and GaN to form heterojunction; the latter semiconductor are essential in many electrical, photoelectrical, and catalytic applications generally requiring an enlargement of the interface area. Thermodynamically, the water splitting reaction is an uphill process that requires a minimum energy of 1.23eV as the Gibbs free energy change is ΔG°=237.2kJ mol-1 or 2.46eV H2O molecule.1 However, a high over potential is needed due to non-idealities in real operations taking into account the water splitting reaction complexity. The water splitting process requires two steps as it is not quite as straightforward as ripping apart the three atoms in H2O. The full reaction requires the participation of two H2O molecules, which are then separated according to the following reduction and oxidation half-reaction.2

Oxidation reaction: (1)

(2)

Overall reaction: (3)

where RHE indicates a reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE).

Given that four-electron water oxidation is the rate-limiting step in the overall water splitting reaction, the development of high-efficiency photoanodes for O2 evolution capable of overcoming the high overpotential requiring to perform this reaction represents an important barrier that must be overcome.3 Hematite (α- Fe2O3) is one of the most promising photoanode candidates as it has a narrow bandgap of ~2.1-2.2eV and allows a ~16.0% theoretical solar-to-hydrogen (STH) efficiency for photoelectrochemical (PEC) water splitting.4–6 Moreover, compared to other narrow bandgap semiconductors, α- Fe2O3 offers many additional advantages, including excellent stability in alkaline solutions, earth abundance, and nontoxicity.3–7 However, α- Fe2O3 has extremely poor electrical conductivity with a hole diffusion length of 2–4nm8 and suffers from a high charge carriers recombination leading to a low PEC performance; the future success of α- Fe2O3 photoanodes in PEC water splitting remains questionable, as α- Fe2O3 itself can hardly achieve rather high PEC efficiency for practical potential use and necessitates modification to improve the PEC performance.

Herein, an overview of the synthesis, modification, and characterization of nanostructured α- Fe2O3 thin film is provided with an emphasis on charge carrier dynamics and PEC properties.9 In the past few years, an increasing number of studies focused on α-Fe2O3 heterostructures, which incorporate the second material to promote charge separation, charge collection, and surface catalysis. Indeed, higher PEC activities have been achieved with such α-Fe2O3 heterostructure-based photoanodes than with their single-component counter- parts, such as WO3/α-Fe2O3,10 ZnO/ α-Fe2O3,11 n-Si/ α-Fe2O3,12 α-Fe2O3/NiO,13 α-Fe2O3:Ti/Cu2O,14 p-Si/ α-Fe2O3/Au,15 and α-Fe2O3 /Gr/BiV1–x MoxO4.16

Table 1 shows a review of the characteristics of some typical α-Fe2O3-based semiconducting heterojunctions that can be found in the literature. Data in Table I include the type of the heterostructure, the fabrication method, the suggested electrons and holes charge transfer and the main photoelectrical properties of these heterostructures. These data are compared with the electrochemically deposited Fe2O3/ZnO heterojunction described in this work.

|

Heterostructure |

Fabrication method |

Suggested charge transfer |

Photoelectrochemistry |

Ref |

|

|

Electron |

Hole |

||||

|

WO3/ α-Fe2O3 |

Sol–gel |

WO3→ α-Fe2O3 |

None |

Photocurrent:22µAcm-2 at 0.8V vs. Ag/AgCl (500W Xe lamp) lec- trolyte: 0.2M Na2SO4 (pH=7.5) |

19 |

|

WO3/ α-Fe2O3 |

spin coating and Spray pyrolysis |

None |

None |

Photocurrent:22µAcm-2 at 0.8V vs. Ag/AgCl; electro-lyte: 0.05M PBS (pH=7) |

20 |

|

ZnO/α- Fe2O3 |

HydrotherµAl and spin coating |

α- Fe2O3→ZnO |

ZnO → α- Fe2O3 |

Photocurrent:1.6µA cm-2 at 0.6V vs. Ag/AgCl; electrolyte:1M NaOH |

21 |

|

α- Fe2O3/Gr/BiV1-x MoxO4 |

HydrotherµAl and spin coating |

BiV1-x MoxO4 → α- Fe2O3 |

α- Fe2O3→BiV1-x MoxO4 |

Photocurrent: 0.39µA cm-2 at 1.5V vs. RHE (64mW cm-2 l ˃ 420nm); electrolyte: 0.01 M Na2SO4 |

22 |

|

α-Fe2O3/ZnFe2O4 |

Spin coating |

ZnFe2O4 → α- Fe2O3 |

α- Fe2O3→ ZnFe2O4 |

Photocurrent: 0.44µA cm-2 at 0.2 V vs. Ag/AgCl; electrolyte: 0.1M glucose and 0.5M NaOH (pH = 13.0) |

23 |

|

α- Fe2O3: Ti/ZnFe2O4 |

HydrotherµAl and surface treatment |

ZnFe2O4 →α- Fe2O3: Ti |

α- Fe2O3: Ti → ZnFe2O4 |

Photocurrent: 0.3µA cm-2 at 1.4 V vs. RHE; electrolyte: 1 M KOH |

24 |

|

α- Fe2O3: Co/MgFe2O4 |

HydrotherµAl and wet impregnation |

MgFe2O4 → α- Fe2O3: Co |

α- Fe2O3: Co →MgFe2O4 |

Photocurrent: 3.34µA cm-2 at 1.4 V vs. RHE; electrolyte: 0.01M Na2SO4 |

25 |

|

p-CaFe2O4/n- Fe2O3 |

HydrotherµAl and two-step annealing |

p-CaFe2O4 → n- Fe2O3 |

n- Fe2O3→ p-CaFe2O4 |

Photocurrent: 0.53µA cm-2 at 1.23 V vs. RHE; electrolyte: 1.0M KOH (pH=13.9) |

26 |

|

α- Fe2O3: Ti/Cu2O |

Spray pyrolysis |

Cu2O →α- Fe2O3: Ti |

α- Fe2O3: Ti → Cu2O |

Photocurrent: 2.60µA cm-2 at 0.95 V vs. SCE (Xe lamp, 150mW cm-2); electrolyte: 0.1M NaOH |

27 |

|

α- Fe2O3/ZnO |

HydrotherµAl |

ZnO → α- Fe2O3 |

α- Fe2O3→ZnO |

Photocurrent: 2.40µA cm-2 at 0.1 V vs. Ag/AgCl. (Xe lamp: 150W); electrolyte 0.1 M NaOH(pH = 13.9) |

Our work |

Table 1 The type of the heterostructure, the fabrication method, the suggested electrons and holes charge transfer and theµA in photoelectrical properties of these heterostructures

The ZnO is a p-type hole-conducting material, transparent in the visible light spectrum range, having a reasonable hole conductivity (≥5×10−4S·cm−1)17 and a good chemical stability.18 In this work, we describe the electrochemical deposition of Fe2O3/ ZnO heterojunction films. ZnO films having various compositions were deposited on smooth Fe2O3 surfaces. The characterization of the films was carried out using FESEM and X-ray diffraction (XRD) techniques.19–27

Fabrication of α-Fe2O3

The flowchart illustrating the synthesis of nanostructured α-Fe2O3 thin films by the hydrothermal method is displayed in Figure 1. Initially, a fluorine-doped tin oxide (FTO) coated glass plate purchased from Pilkington glass company (USA), was cut into small rectangular pieces having a surface of 3x1cm2 to serve as a starting substrate. These pieces were ultrasonically pre-cleaned by sequential rinses with acetone, distilled water, and ethanol. The hydrothermal bath was an aqueous solution containing a solution 0.15M FeCl3, 1M NaNO3.28–30 Some drops of hydrochloric acid (HCl) were added to adjust the pH of the mixture to 1.5. All chemicals were purchased from Sigma Aldrich and used as received without any additional purification. Double deionized water, exhibiting a resistivity close to 15MW·cm was generated by a Milli-Q academic ultra-pure water purification system (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). Once the solution was prepared, some FTO glass substrates were placed at the bottom of a Teflon recipient. Only 20ml were transferred to the recipient so that the substrates were partially immersed in the solution. Then, the recipient was inserted in a stainless-steel autoclave. The filled autoclave was tightly sealed before being heated at 100°C for 6h in an oven. Finally, the system (autoclave with the samples) was naturally cooled down to room temperature.

Under hydrothermal conditions, the aqueous solution enables the Fe3+ hydrolysis ions with OH-, producing iron oxide nuclei, as described by the following reaction (1):

(4)

Finally, a uniform yellowish layer of akageneite β-FeOOH covered the FTO/glass substrates uniformly. The akageneite-coated substrates were then washed with deionized water and subsequently introduced in a muffle furnace to be sintered in air at 550°C for 4 hours. At theend of this calcination step, the β-FeOOH was converted into α-Fe2O3. Correspondingly, as illustrated in Figure 1, the color of the substrate turned from yellow to red-brown indicating a phase transition from β-FeOOH to α-Fe2O3.Thechemical reaction expected to occur during this phase transition is represented by the reaction displayed below (2):

All reagents used in the experimental process were analytically pure. In order to hydrothermally grow ZnO nanostructures, zinc nitrate hexahydrate (Zn(NO3)2.6H2O) and hexamethylenete-tramine (HMT, C6H12N4) were exactly weighed using an analytical balance with an accuracy of 10−4g, and were dissolved in deionized water, producing precursor solution of 40mL at a concentration of 0.05M. The ZnO layers was hydrothermally deposed onto the surface of the as-treated FTO substrate with the size of 2cm×1cm to reduce the lattice mismatch between ZnO and the substrate.

Process parameters were as follows: hydrothermal time, 4h; temperature 150°C. Finally, the device was transferred to an electric oven and heated at a constant temperature of 90°C for 5 h, to develop the ZnO nanostructure. After cooling to room temperature (defined as 20–25°C), the product was gradually washed with distilled water and then dried naturally in air (Figure 2).

Materials characterization

The crystal structure of α-Fe2O3 and α-Fe2O3/ZnO heterojunction were investigated by XRD (Rigaku Ultima IV diffractometer in the Bragg-Bentano configuration) using the CuKα radiation (λ=1.54060Å). The microstructural and elemental analyses were characterized using a Zeiss ULTRA 55 model scanning electron microscope (SEM) equipped with an energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) system. To determine the band gap energy was estimated from the optical absorption, which was measured by recording the transmission spectra using a UV-Visible spectrophotometer (Ocean Optics HR4000) coupled to an integrating sphere (in order to collect both specular and diffuse transmittance).

Photoelectrochemical and electrochemical analyses

The PEC measurements were performed in a quartz cell to facilitate the light reaching the photoelectrode surface. The light exposed surface of the working electrode is 0.25cm2. The electrolyte used in all PEC measurements is 1.0M NaOH (pH=13.6). The electrolyte was purged with nitrogen gas before the experiments in order to prevent any possible reaction with dissolved oxygen at the counter-electrode. A potentiostat/galvanostatAutolab PGSTAT302N (Metrohm, Netherlands) with a Pt rod counter-electrode and an Ag/AgCl saturated in 3 M KCl reference electrode was used.The films were illuminated with a 150 W Xenon lamp (PLSSXE300/300UV) coupled to a chopper and a selectiveblue filter (l>400nm).The set-up was completed with an automatic shutter and a filter box. The whole system was controlled by a homemade software. The chronoamperometry curves of the films were also obtained at +0.1 V both in dark and under illumination with anintensity of about1 SUN (100mW cm-2) at the film surface.

Morphological characterization

Figure 3A& Figure 3B display the FESEM images of the ZnO and the α-Fe2O3 films deposited on FTO substrates, respectively. FESEM image of ZnO (Figure 3A) show that the ZnO nanorods are uniformly distributed on the substrate. Figure 4B shows the morphology of the α-Fe2O3 films, revealing nanostructured grains having a size dimension of about 20nm. Figure 4C show the ZnO films deposited on α-Fe2O3 covered substrates at different magnifications. FESEM top view images in Figure 3C reveal that the ZnO: α-Fe2O3 nanorods have bigger size than the ZnO.

EDX analyses

The stoichiometric proportions of the ZnO films were estimated by EDX analyses. Figure 4A & Figure 4B show EDX emental analyses of the α-Fe2O3 and ZnO, respectively. The line observed at 0.72keV corresponds to the L line of Fe, while the oxygen K line is peaking at 0.525keV. The calculated atomic ratio of Fe and O is approximately equal to 2:3, which well agrees with the stoichiometric composition of α-Fe2O3.The percentages of the elements calculated from the EDX spectra are shown in the inset of Figure 4. Figure 4B shows the EDX spectrum of the ZnO film; only lines corresponding to Zn and O are observed. The inset in Figure 4B displays the calculated percentages for the elements of the ZnO film.

Figure 5 shows the spatial distribution of ZnO+α-Fe2O3, where Fe and O are three-dimensionally well-distributed in the ZnO film. The atomic percentage calculated from the EDX analyses indicates that the Zn to O ratio is 1:1. It can be concluded that the ZnO crystals can uniformly encapsulate the α-Fe2O3 structure.

Structural characterization

Figure 6 shows the XRD patterns of the Fe2O3 and ZnO layers deposited on FTO substrates. The XRD patterns of the Fe2O3/ ZnO bilayer and the FTO substrates are also shown. The XRD peaks of theα-Fe2O3 filmsare observed at 2θ=24.1°, 33.1°, 35.6°, 40.9°, 49.4°, 54.0° and 64°, which correspond to the (012), (104), (110), (113), (024), (116) and (300) planes of the hematite phase, respectively. The dominant peaks are associated to the (104) and (110) planes. The diffraction peaks of the trigonal structure of the α-Fe2O3matches well with the reference pattern JCPDS card file n°33-0664, which corresponds to the space group R3c (167) with lattice parameters a=b=5.03nm and c= 13.74nm.

The XRD pattern of the product was shown in Figure 6. All of the diffraction peaks can be indexed as those from the known quartzite structured (hexagonal) ZnO with lattice constants of a=0.325nm and c=0.521nm. No characteristic peaks from other impurities were detected. XRD investigations indicated the ZnO nanowire were grown along the [002] direction.

For the Fe2O3/ ZnO bilayer, all peaks match the Fe2O3 and ZnO patterns except those marked with asterisks that come from the FTO substrate.

Optical properties

Figure 7A & Figure 7B show the transmission spectra of the ZnO film and the α-Fe2O3, respectively. The energies of the optical bandgaps can be determined from the transmission spectra.31 The transmittance spectrum of ZnO (Figure 7A) shows a high optical transmission value in the visible range. A significant increase in the absorption below 364nm can be assigned to the intrinsic band gap absorption of ZnO. It appears that α-Fe2O3 films have a high absorbance in the visible region, indicating their applicability as an absorbing material (Figure 7B).32

To calculate the optical band-gap energy () of the films, the absorption coefficient can be estimated as follows:

(6)

The relation between the absorption coefficient α and the energy of the incident light hν is given by:33

(7)

where α is the absorption coefficient, A is a constant, h is the Planck’s constant, ν is the photon frequency, Eg is the optical band gap, and n is equal to 2 for direct transition, and to 1/2 for indirect transition. According to the Tauc plot ((αhν) 2vs.hν) (Figure 8A), the optical band gap Eg of the typical ZnO film is about 3.4eV. Jaffe et al.34 predicted the existence of an indirect bandgap of 3.5eV from an electronic band structure model calculated using the density functional theory, although absorption measurements performed on ZnO samples indicated the presence of an indirect bandgap of 3.9eV.

Figure 8B depicts the Tauc plot of α-Fe2O3 films. One may point out a direct band gap energy of about 2.1eV, which is smaller than that of bulk α-Fe2O3 (2.3eV).35

Photoelectrochemical measurements

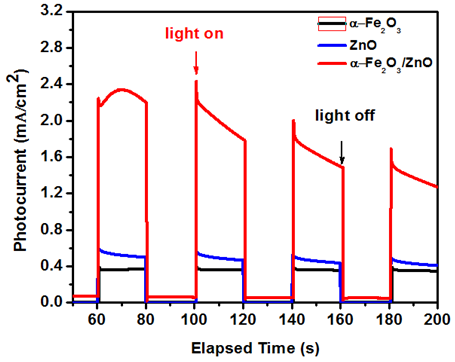

The measurements of thephotocurrent under pulsed light were acvhieved using a chronoamperometry technique (Figure 9). In the steady state, the α-Fe2O3/FTO electrode shows aphotocurrent density f about 0.4mA/cm2.However, the α-Fe2O3/ZnO/FTO heterojunction shows a photocurrent densityof about 2.4mA/cm2, which is 6 times bigger than that of the α-Fe2O3/FTO electrode. Figure 9 shows the variation of the photocurrent density versus elapsed time during switch on/off of light for both α-Fe2O3/FTO and α-Fe2O3/ZnO/FTO electrodes. The photocurrent density drops in the first two cycles and then was steady and quasi-reproducible after several on–off cycles of light, with no overshoot at the beginning or the end of the on–off cycle, indicating that the direction of the electron diffusion isfree from grain boundaries, which can create traps to hinder electron movement and slow down the photocurrent generation.36

Figure 9 Photocurrent intensity for of ZnO, α-Fe2O3 and the Fe2O3/ZnO electrodes under successive on/off illumination cycles, measured in 1M NaOH electrolyte under a bias potential of +0.1V.

It is believed that deposition of ZnO on α-Fe2O3 enhanced the photoactivity of the photoanode in two aspects: (i) the p–n junction can effectively extract holes and separate charge carriers, leading to enhanced photocurrent, and (ii) The loading of the heterojunction photoanode with CuSCN further facilitates the electron transfer at the electrode/electrolyte interface and thus enhancesthe photoelectrochemical water oxidation.

Semiconducting materials such as n-Fe2O3 and ZnO were successfully electrodeposited on FTO substrates. This enables us to study the energetic behavior of both semiconductors and the n-Fe2O3/p-ZnO heterojunction performancesas regard to photoelectrochemical applications.FESEM shows that ZnO can easily grow thicker to cover the α-Fe2O3 substrate. The photoelectrochemical performance of the nanostructured α-Fe2O3/ZnO heterojunction is higher than that of FTO/α-Fe2O3 and FTO/ZnO.A maximum photocurrent density of 2.4 mA/cm2 was exhibited for the α-Fe2O3/ZnO photoelectrode. The improvement of the photocurrent density is attributed of two major combined factors: (i) generation of anelectric field inthe heterojunction that suppresses the recombination of photogenerated charge carriers and (ii) application of an adequate external bias favoring the transfer and separation of the photogenerated charge carriers in the α-Fe2O3/ZnO heterojunction. Enhancement in the photocurrent density has also been attributed to an appropriate band edge alignment of the semiconductors that enhances lightabsorption inboth semiconductors.

This work was supported by the Ministry of High Education and Scientific Research (Tunisia), Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (ENE2016-77798-C4-2-R) and Generalitat Valenciana (Prometeus 2014/044).

None

©2018 Bouhjar, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.