Journal of

eISSN: 2473-0831

This study provides a confirmation of the need to adopt the HACCP method (Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point) in slaughterhouses as a tool to eradicate the Human Brucellosis. Indeed this assessment made in our study is an indirect indicator for the presence of the disease in a country on one hand, but also about the transmission risk of the disease from animals to humans in a professional context at high risk, and secondarily to the general population by food consumption. Slaughterhouses are the most propitious places for the transmission of this disease to humans and also the point spread of this zoonosis seen as a biological danger to the population. The general objective of this study made at the Slaughterhouse of the Bertoua city (East Region of Cameroon) was to evaluate the errors related to the professional activity of slaughterhouse workers with regard of the Human Brucellosis, in a context where the application of the HACCP method is not respected. Its specific objectives were to detect the presence of the Human brucellosis in that slaughterhouse, to determine its prevalence among slaughterhouse workers and to make them more aware about the existence of this zoonosis. We included in our study, all slaughterhouse workers from the city of Bertoua, who signed the informed consent form for the participation in the study, and also the absent staff due to illness. We excluded from our study any slaughterhouse workers absent at the time of data collection and reported to be in good health by their colleagues. At the end of this study, we found a prevalence of 31.4% for human brucellosis cases due to a bad slaughtering system which did not comply with the safety and hygiene measures in force. Professional exposure was related to the failure to use individual protection equipments (boots, aprons, goggles, bibs, gloves and helmet) and collective protection equipments (disinfectants/antiseptic and slaughterhouse toilets). The Biological signs related to the Human Brucellosis found among sick slaughterhouse workers hospitalized in different health care structures from the city were: neutropenia associated with an increase of ESR, CRP and transaminases. The most frequent symptoms noticed among them were: asthenia, fever, generalized pain and headache.

Keywords: human brucellosis, slaughterhouse, slaughterhouse workers, rose bengal test, prevalence, East Cameroon

Brucellosis is a zoonosis caused by bacteria of the genus Brucella. Its extension is global with a predominance in the Mediterranean basin, Central America (Mexico) and South (Peru), Middle East, Asia (India, China) and in black Africa, where it still poses a real public health problem.1 On a worldwide scale, brucellosis affects more than 500 000 individuals each year.2–5 The incidence of the disease varies among countries and regions ranging from 0.125 to 200 cases per 100,000 populations.2,3 Six species (B. abortus, B. melitensis, B. suis, B. ovis, B. canis, B. neotomae) are implicated in the natural infection of several animal species like cattle, goats, pigs, rodents, carnivores and other mammals.6 Human attacks are attributed to 4 from 6 species of Brucella namely B. melitensis, B. suis, B. abortus and B. canis.6 The entering of the germ is effected by direct contact of the individual with infected materials such as animal secretions, abortion products, urine, manure, carcasses of animals. In Cameroon, many surveys were conducted in area of the north Cameroon from 1966 to 2010 and the results of these surveys were between the infection rate of bovine from 10% to 83%.6–8 Studies conducted in Adamawa, Bénoué, Diamaré and Ménua have yielded prevalences of bovine Brucellosis which ranged from 6.5 to 12.5%,7–10 although the WHO estimates indicate more than 500 000 new human cases per year. The epidemiology of human disease is closely related to animal infection. It is why we have focused our attention on slaughterhouses which are the most propitious places for the transmission of this disease to humans and as well as its spread to the human population by food consumption. The general objective of this study was to evaluate the errors related to the professional activity of slaughterhouse workers with regard of the Human Brucellosis, in a context where the application of the HACCP method is not respected (example of the slaughterhouse from the Bertoua city in Cameroon), and its specific objectives were to detect the presence of the Human Brucellosis in that slaughterhouse, to determine its prevalence among slaughterhouse workers and to make them more aware about the existence of this zoonosis.

Study design, sampling and population

We carried out a transversal study with prospective data collection from 26th April 2015 to 30th October 2015 among 89 slaughter house workers from the city of Bertoua (East Cameroon), which is a professional category that has more risk to contact the brucellosis. The workers of the slaughter house from Bertoua belonged to the following categories: meat carvers, cleaners, butchers, veterinarian technicians and administrative staff (Table 1).

Criteria for inclusion and exclusion

We included in our study, all slaughter house workers from the city of Bertoua, who signed the informed consent form for participation in the study, and also the absent staff due to illness. We excluded from our study any slaughter house workers absent at the time of data collection and reported to be in good health by their colleagues.

Data collection

The Participants included in the study were recruited randomly at the slaughter house. The sick staff was recruited in homes and in the different health care structures from the city. Selected participants signed an informed consent form, and a unique identification number was assigned to each participant sequentially in the running order; and with confidentiality. Participants were interviewed face to face andthe data were collected using a structured questionnaire with socio-demographic data (age, educational level, marital status, residence, professional occupation, etc.), clinical history related to the Human Brucellosis, risk factors associated with the disease (professional and non-professional exposure), use of individual and collective protection equipments, and knowledge about brucellosis.

Biological and clinical diagnosis

After collection of blood samples, the serum was prepared by centrifuging the blood at 1500trs for 5 minutes. The serum obtained were introduced into the eppendofs tubes and stored frozen at -20°C until use. The biological diagnosis of this zoonosis was done using two serological tests including: Rose Bengal test and ELISA (Linked Immunosorbent Assay) for the positive cases previously confirmed. We used these two serological tests to improve the specificity of diagnosis to the antigen and also to limit the false positives cases. The clinical diagnosis of the sick staff necessary for the clinical study of the disease was made by the team of doctors and nurses working in different health care structures from the city.

Statistical analyses

The data obtained were analyzed with the version 2.13 of R software and Excel software. The Chi-square test was used to compare the percentages and the accepted significance was fixed to 5%.

Ethical consideration

We have obtained the agreement of the Department of Biomedical Sciences from the University of Ngaoundere and also the authorization of the Departmental Delegate of Public Health from that division (Lom and Djerem) which served us as a springboard to access in the different health care structures from the city. Additionally, an informed consent was obtained before the data collection from our participants.

Sociodemographic characteristics of slaughterhouse workers

The slaughterhouse workers from the city of Bertoua were around 134 spread over different positions. We were able to recruit 89 participants for this study that is 66%, among which, 98% were the men, 60% were married and all our participants were instructed. The average age was 27 years ± 12.11, ranged from 16 to 56 years, and the predominant age group was the one of 20 to 30 years old (Table 2).

Classification of slaughterhouse workers

The meat carvers were the most dominant workers with 44% of study participants and the gut area (work area) was the one which also had the highest number of participants with 38% (Table 1).

|

Variables |

N(%) |

|

Age Group (n=89): |

|

|

≤ 20 Years old |

8(9%) |

|

] 20 to 30] |

36(40%) |

|

] 30 to 40] |

28(31%) |

|

> 40 Years old |

17(20%) |

|

|

P. value=0.02 |

|

Sex (n=89): |

|

|

Men |

87(98%) |

|

Women |

2(2%) |

|

|

P. value=0.005 |

|

Educational level (n=89): |

|

|

Koranic School |

18(20%) |

|

Primary School |

39(44%) |

|

Secondary School |

24(27%) |

|

Graduate Level/University |

8(9%) |

|

|

P. value= 0.01 |

|

Matrimonial Status (n=89): |

|

|

Single |

35(39%) |

|

Married |

53(60%) |

|

Widow (er) |

1(%) |

|

|

P. value= 0.66 |

|

Residence (n=89): |

|

|

Monou |

19(21%) |

|

Haoussa |

31(35%) |

|

Mont-Febe |

18(20%) |

|

Tigaza |

6 (7%) |

|

Nyangaza |

4(5%) |

|

Tidamba |

11(12%) |

|

|

P.value= 0.005 |

Table 1 Distribution of slaughterhouse workers according to the sociodemographic characteristics

|

Variables |

N (%) |

|

Activities (n=89): |

|

|

Meat Carver |

39(44%) |

|

Butcher |

26(29%) |

|

Cleaning Agent |

17(19%) |

|

Administrative Staff |

2(2%) |

|

Veterinarian Technician |

5(6%) |

|

|

P. value=0.05 |

|

Working Area (n=89): |

|

|

Slaughter area |

26(29%) |

|

Gut area |

34(38%) |

|

Cutting area |

12(14%) |

|

Administrative area |

2(2%) |

|

Waste dumping area |

9(10%) |

|

Dispatching area |

6(7%) |

|

|

P. value=0.03 |

Table 2 Distribution of slaughterhouse workers according to their activities

N, number of participants in each group; n, sample size; Accepted significance: 5%.

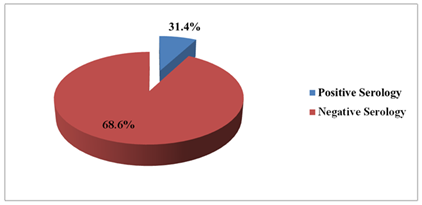

Analysis results of collected samples with the rose bengal test

Among the 89 collected samples, 28 positive cases and 61 negative cases have been recorded with the Rose Bengal test; that is a prevalence of 31.4% (P. value = 0.002) (Figure 1). These positives cases were found in the professional category of meat carvers and cleaners in frequent contact with the marshy area used for dumping of slaughterhouse wastes (slaughterhouse did not use the incinerator).

Figure 1 Graphical representation of the analysis results of collected samples with the Rose Bengal test.

Results obtained with the confirmation test (ELISA test)

The 28 positive serums with the Rose Bengal test among the 89 tested serums were subjected to the immuno-enzymatic test ELISA for confirmation of their positive status. 25 (89.2%) of the 28 positive cases with the Rose Bengal test were confirmed positive by the ELISA test, and 3 (10.8%) of these 28 positive cases were considered as uncertain cases. (P. value = 0.005) (Figure 2).

Professional exposure of slaughterhouse workers

During our study, we noticed that only the cattle were slaughtered in that slaughterhouse and the skin contact with the blood and animal secretions was frequent with respective percentages of 78% and 46% (Table 3).

|

Variables |

N(%) |

|

Contact with Blood (n = 89): |

|

|

Skin |

69(78%) |

|

Eyes |

13(15%) |

|

Contact with the contaminated soil by the blood |

82(92.1%) |

|

Mouth |

17(19.1%) |

|

P. value= 0.005 |

|

|

Contact with Animal Secretions (n=89): |

|

|

Skin |

38(46%) |

|

Eyes |

21(23%) |

|

Mouth |

21(23%) |

|

P. value=0.03 |

|

|

Other Risk Contact (n=89): |

|

|

Contact with the genital matrix |

4(5%) |

|

Contact with abortion products |

4(5%) |

|

P. value= 0.01 |

|

Table 3 Distribution of slaughterhouse workers according to their professional exposure

N, number of participants in each group; n, sample size; Accepted significance: 5%

Use of individual and collective protection equipments

We noticed that the participants in our study did not use helmets, goggles and bibs, whereas these protection equipments should be mandatory to them. Their frequency about the use, of aprons, gloves and disinfectants/antisepticswas also very low (Table 4).

|

Variables |

N(%) |

|

Use of individual protection means (n = 89): |

|

|

Use of boots |

34(38%) |

|

Use of aprons |

16(18%) |

|

Use of Helmets |

/ |

|

Use of bibs |

/ |

|

Use of goggles |

/ |

|

Use of gloves |

16(18%) |

|

P. value=0.05 |

|

|

Use of Collective Protection Means (n = 89): |

|

|

Use of disinfectants/antiseptic (for hand washing) |

19(21%) |

|

Use of disinfectants/antiseptic (for washing boots, gloves etc.) |

/ |

|

Use of slaughterhouse toilet |

68(76%) |

|

P. value=0.03 |

|

Table 4 Distribution of slaughterhouse workers according to the individual and collective protection means.

N, Number of participants in each group; n, sample size; Accepted significance: 5%.

Symptoms observed among the sick staffs infected with the human brucellosis

Asthenia, fever and generalized pain were the most frequent symptoms noticed among the sick staffs, recruited in the different health care structures from the city of Bertoua during the period of our study (Table 5).

|

Clinical signs |

Yes |

No |

P. value |

|

Asthenia |

25 |

3 |

0.41 |

|

Fever |

25 |

3 |

0.001 |

|

Nausea / vomiting |

21 |

7 |

0.01 |

|

Profuse sweat |

19 |

9 |

0.26 |

|

General pain |

25 |

3 |

0.39 |

|

Headache |

21 |

7 |

0.0003 |

Table 5 Distribution of the sick staff infected with the Human Brucellosis according to their symptoms.

Accepted significance: 5%

Biological signs noticed from the sick staff infected with the human brucellosis

We noticed the presence of neutropenia accompanied by an increase of the ESR, CRP and transaminases among the sick staffs (Table 6).

|

Biological signs |

Yes |

No |

P. value |

|

Neutropenia |

25 |

3 |

0.01 |

|

ESR increased |

27 |

1 |

0.04 |

|

CRP increased |

27 |

1 |

0.04 |

|

Transaminases increased |

28 |

/ |

0.6 |

Table 6 Distribution of the sick staff infected with the Human Brucellosis according to their biological signs.

ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CRP, protein c reactive; Accepted significance=5%.

Dietary exposure of the sick staffs infected with the human brucellosis

We noticed that all the sick staffs ate braised meat and 19 (68%) of them also consumed raw milk (Table 7).

|

Risk factors |

Consumption of braised meat |

Consumption of raw milk |

||

|

Serology |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

|

Positive |

28 |

/ |

19 |

9 |

|

P. value |

0.16 |

0.01 |

||

|

r |

0.009 |

0.05 |

||

Table 7 Distribution of the sick staffs infected with Human Brucellosis according to the dietary Exposure.

r: correlation coefficient; Accepted significance: 5%.

Limits of the study

The lack of funds did not allow us to do an additional study about the prevalence of bovine brucellosis in that slaughterhouse in order to better assess the transmission risk of this zoonosis in that slaughterhouse, which had a bad slaughtering system of cattle that did not comply with safety and hygiene measure in force.

This study actually confirmed the existence of human brucellosis among slaughterhouse workers. We found a prevalence of 31.4%. Despite the difference in the methodology followed, this result is quite comparable to the one from the study performed in 2012 by Khalili among slaughterhouse workers from Iran which reported a prevalence of 58.6%.11 In 2008 Pakistan reported a prevalence of 21.7%,12 the prevalence was also around 25.5% in India according to a study in 201113 and 35% in Saudi Arabia in 2011.14 The prevalence obtained in our study was attributable to an unsafe and unhealthy slaughterhouse and also to a professional behavior potentially at risk for the transmission of brucellosis noticed during the period of our study (Figure 1).

The professional exposure to Human Brucellosis was made by direct contact with the infected animal or its viscera and secretions but also with the contaminated soil with the bacterium.15 Among our study participants interrogated, 78% had direct contact with animal blood through the skin, 46% had a direct contact with animal secretions through the skin and 10% had contact with the genital matrix and abortions products. We noticed also that these slaughterhouse workers have been in contact with blood and animal secretions through the eyes and mouth (Table 3). The failureto use individual protection equipments (boots, aprons, goggles, bibs, gloves and helmet) and collective protection equipments (disinfectants/antiseptic and slaughterhouse toilet) can give an explanation to these results (Table 4).

The slaughterhouse workers infected with Human Brucellosis worked as meat carvers and cleaners and were exposed daily to blood, viscera and abortion products. They did not use individual gloves or disinfectants / antiseptics for hand washing; which theoretically increased the exposure risk to infection. They were also exposed daily to the marshy area used for dumping the slaughterhouse wastes. The slaughtering system of that slaughterhouse from Bertoua, did not use safety and hygiene measures in force.

Regarding the symptomatology of the disease, asthenia, fever, and generalized pain were the most frequent symptoms among our sick participants, recruited in different health care structures at the city of Bertoua (Table 5). Additionally to this, we also noticed the presence of headache, nausea/vomiting and profuse sweating among some patients. This remark was also made by Boukary and Dantouma in their studies in 2010 and 2008 respectively.3,16 The biological signs also noticed among these sick participants were: neutropenia associated with an increase of ESR, CRP and transaminases. This remark was also made by Mohamed Chakroun in his study in 2007 about the Human Brucellosis.1

Regarding the brucellosis transmission by food, the exogenous contamination of the food (by the external environment during the slaughter and preparation operations) seemed to prevail over the endogenous contamination (animal contamination before slaughter). The non-compliance with safety measures and hygiene in force observed during our study seemed to facilitate the introduction of bacteria into the slaughterhouse by the skin and the digestive contents of the cattle and also by the staff. We also noted that the consumption of braised meat added to the one of raw milk increased the risk of disease occurrence. All our participants infected with Human Brucellosis, ate braised meat and 68% of them also consumed raw milk (Table 7). This remark departs somewhat from the one made by Doutouma in his study in 2008, which stated that only the consumption of raw milk was a risk factor for Brucellosis.16

This study provides a confirmation of the need to adopt the HACCP method (Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point) in slaughterhouses as a tool to eradicate the Human Brucellosis. Indeed this assessment made in our study is an indirect indicator for the presence of the disease in a country on one hand, but also about the transmission risk of the disease from animals to humans in a professional context at high risk, and secondarily to the general population by food consumption. We found a prevalence of 31.4% for Human Brucellosis cases, due to a bad slaughtering system which did not comply with the safety and hygiene measures in force. The professional exposure was related to the failure to use individual protection equipments (boots, aprons, goggles, bibs, gloves and helmet) and collective protection equipments (disinfectants/ antiseptics for hand washing and personal protection equipments) as well as the use of the slaughterhouse toilets, which should be mandatory to them during their professional activity. The biological signs noticed among our sick participants infected with this zoonosis were: neutropenia associated with an increase of ESR, CRP and transaminases. The most frequent symptoms also noticed among them were: asthenia, fever, generalized pain and headache.

Authorship contribution

All authors contributed to the designing, preparation, editing, and final review of the manuscript.

Authors thank the collaborators of their respective institutions for the comments on the manuscript.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

None.

© . This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.