International Journal of

eISSN: 2574-8084

Case Report Volume 8 Issue 4

1GenesisCare Radiation Oncology, Mater Hospital, Crows Nest, Australia

2Sun Doctors, 200 Crown Street, Wollongong, Australia

3GenesisCare Centre for Radiation Oncology, Waratah Private Hospital, Hurstville, Australia

Correspondence: Prof Gerald Fogarty, GenesisCare Radiation Oncology, Mater Hospital, 25 Rocklands Rd, Crows Nest, NSW, 2065, Australia, Tel +612 9458 8050, Fax +612 9929 2687

Received: November 05, 2021 | Published: November 25, 2021

Citation: Fogarty GB, Farrow C, Bartley J, et al. Circumferential volumetric modulated arc radiotherapy of the lower legs–a technique described in a case of disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis. Int J Radiol Radiat Ther. 2021;8(4):183-192. DOI: 10.15406/ijrrt.2021.08.00313

A case of a fit 65-year-old male with a long history of recalcitrant Disseminated Superficial Actinic Porokeratosis (DSAP) treated with Volumetric Modulated Arc Radiotherapy (VMAT) is presented. The whole circumference of both lower legs from knees to ankles were simultaneously treated to 43.2 Gray (Gy) in 24 fractions, one fraction short of the prescription dose of 45 Gy in 25 fractions. There was in-field clearance of DSAP at ten weeks. This is the first publication of circumferential VMAT treatment of the skin of the lower legs. More follow up is required to see the durability of control of DSAP, and more research is needed to test the generalisability of this technique.

Keywords: Radiotherapy, circumferential treatment, lower legs, volumetric modulated arc therapy, disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis

Disseminated Superficial Actinic Porokeratosis (DSAP) is characterised by small, dry, scaly brown patches with a distinctive border over the skin of the body, particularly in sun exposed areas like the lower arms and legs.1,2 DSAP usually starts during the third or fourth decade and may be inherited in an autosomal dominant manner or may occur in people with no family history.3 Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) or Bowen’s disease may develop within patches, and so it may be considered as a precursor form of extensive skin field cancerisation (ESFC).4 There is no standard treatment for DSAP, and current treatment is generally not effective in the long-term.1,2

Volumetric Modulated Radiotherapy (VMAT) is ideal for treating large convex areas of ESFC.5 Treating the lower legs has been a relative contraindication for treating lesions with definitive radiotherapy (RT)6 let alone ESFC of the lower legs. Lower leg VMAT for ESFC has been problematic. Our national protocol7 for lower legs requires a mandated break of at least two weeks after 18-20 Gy, treating one leg only at a time, and sparing a strip of skin to avoid chronic lymphoedema. The latter is difficult when the full circumference of the lower leg is involved, as it is in DSAP.

We present a case of DSAP of bilateral lower legs treated simultaneously to one fraction short of the full prescription dose. The full circumference of both legs were treated simultaneously with a good outcome at 10 weeks.

A fit motivated 65-year-old male had suffered from DSAP for 30 years. He had treatment for various small keratinocytic cancers (KCs) treated in sun exposed areas, and field treatments such as 5 fluorouracil cream for symptomatic eruptions of DSAP, without lasting effect. His current strategy at the time of presentation was a review every 3 months by his local skin doctor. The doctor would just cauterise every lesion that looked as though it would transform into a KC, treating about 50 lesions a year.

The most effective treatment to date was photodynamic therapy (PDT) to both legs. This was painful during administration, with pain lasting for several weeks afterwards. The pain was described as “lava” under the skin especially when going from lying to standing. The pain was not pulsating. The PDT had a good effect lasting for 2 to 3 years but then the DSAP reappeared within the PDT treated volumes.

He has never had any DSAP on the face or torso. His mother had suffered from DSAP. He has one sibling, and that sibling had no sign of DSAP. He had had a left tibial osteotomy in the past but had no history of vascular problems, especially no lower leg varicosities. His main areas of concern with DSAP were bilateral lower legs. He did remark that people had noted his disease and at times he covered his legs for this reason. He lived over 100 kms from the treatment centre and wanted both legs treated at the same time for convenience.

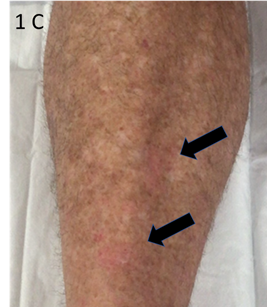

Examination revealed circumferential involvement of both lower legs, worse anteriorly, consistent with sun exposure. The field change extended onto the proximal dorsum of both feet. There were no active KCs in the leg fields. (Figure 1) The rationale, process, and side effects of VMAT for ESFC of both legs was explained and he consented to treatment and proceed to planning. Prior to planning he was reviewed by a lymphoedema physiotherapist and was prescribed compression therapy consisting of below knee flat knit compression stockings and compression wrap garments. The plan was for him to wear these from the beginning of therapy except at night. The garments cost $AUD 500 per leg.

Figure 1C C – Lower legs at presentation – close up of anterior left leg showing typical skin lesions of DSAP. Black arrows indicate small, dry, scaly brown patches with a distinctive border all over the skin.

Figure 1 Lower legs at presentation.

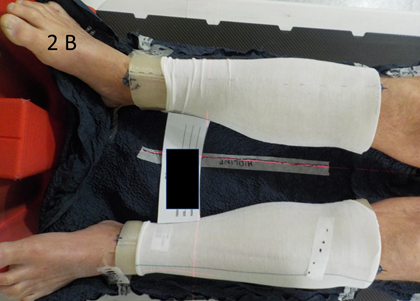

In the planning process our national protocol7 was followed. Briefly, while on the computer tomography (CT) simulation scanner, he was immobilised in vacuum bag (SecureVacTM Cushions, NL Tek, Willetton, Western Australia) and asked about the most symptomatic areas. These extended from proximal dorsum of both feet to the knee joints bilaterally. The areas were then decreased to measure 40cms each in maximum length as this was the limit of the three-dimensional printed bolus (3DPB) (3D One, Salisbury, QLD, Australia). A longer field would have meant that each leg would need 4 pieces of 3DPB rather than 2. The areas for treatment were marked superiorly and inferiorly by the RO with a skin marker. The lower borders were at the eminence of the medial malleoli. To help with following any lymphoedema, graduations at 5, 10 and 15 cms above the lower border were marked. See Figure 2. The circumferences of the legs were measured by tape measure at those levels and recorded as baseline.

Figure 2A At planning the patient was immobilised in vacuum bag and the areas for treatment were marked superiorly and inferiorly by the RO with a skin marker, as indicated by horizontal arrows. These fields measured 40cms in length. The lower borders were the eminences of the medial malleoli. To help with following any lymphoedema, graduations at 5, 10 and 15 cms above the lower border were marked. All RO marks were wired to enable visualistion on the CT planning scan.

Figure 2B At the second planning CT the bi-valved 3DPB was applied and kept in place with TubigripTM. This scan was fused with the first scan and used for RO contouring.

Figure 2 At planning.

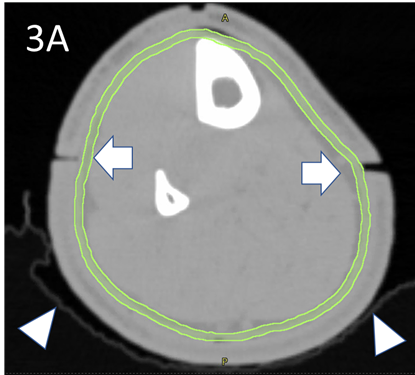

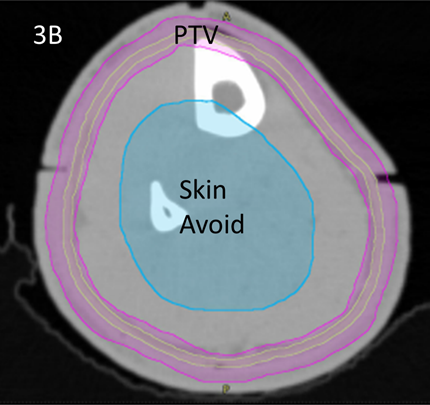

Wires were placed over all RO marks to capture these positions on the CT scan. The latter was done at 2mm increments. Bi-valved 3DPB was then ordered and was fitted at a second simulation session. The RO then contoured the clinical target volume (CTV) and planning target volume (PTV)8 according to the national protocol7 using MIM MaestroTM planning software. A contour volume called “Skin Avoid” was created by having a structure that extended on all the slices on which there was a PTV. This volume was made by the RO and was 1.5cm inside the PTV into the centre of the leg. The Skin Avoid structure was prescribed to receive a dose less than a mean of 25 Gy. See Figure 3.

Figure 3A The RO drew the contour of the epidermis as the CTV on the planning CT, here in light green. This is usually 2-4 mm in thickness. The white triangles denote the snugly fitting vac bag. White arrows denote the joints in the 3DPB at baseline.

Figure 3B The RO also contours the PTV, in magenta, according to the national protocol7 using MIM MaestroTM planning software. The PTV was prescribed 45Gy in 25 fractions. A volume called “skin avoid” was created by having a structure, here in cyan, that extends on all the slices on which there is a PTV. It is made by being inside and 1.5cm from the PTV into the centre of the leg. The Skin Avoid structure was prescribed to receive a dose less than a mean of 25 Gy.

Figure 3C Dosimetry with dose wash minimum set at 42.5Gy showing excellent conformality and homogeneity to the PTV.

Figure 3D Dosimetry with dose wash minimum set at 25Gy showing excellent avoidance of the skin avoid structure.

Figure 3 Contouring and dosimetry.

A prescription was generated for PTV coverage of 45 Gy and Skin Avoid mean less than 25Gy over 25 fractions with a two week break as per protocol. Planning was done using Eclipse Version 16.1 (Varian, Palo Alto, USA). Planning constraints where met (See table 1). Avoidance structures were created to avoid treating the contralateral leg. Quality assurance was passed successfully. The case was presented to a peer review committee and the course of treatment was not thought unreasonable given the patients history and circumstances.

Volume |

Volume |

Min |

Max |

Mean |

Homogeneity |

Conformity |

Right CTV |

319 |

39.3 |

48.9 |

45.1 |

1.088 |

1.0 |

Right PTV |

1071 |

39.5 |

48.9 |

44.6 |

1.088 |

0.956 |

Right SA |

1001 |

8.6 |

36.5 |

21.5 |

NA |

NA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Left CTV |

298 |

33.3 |

48.6 |

44.9 |

1.081 |

0.996 |

Left PTV |

1030 |

25.3 |

49.0 |

44.3 |

1.090 |

0.946 |

Left SA |

897 |

9.4 |

37.8 |

21.0 |

NA |

NA |

Table 1 Planning volumes sizes and doses

CTV; clinical target volume, PTV; planning target volume, SA; skin avoid volume, Max; maximum, min; Minimum, Gy; Gray, cm3; cubic centimetre

He was treated on a HalcyonTM Linear Accelerator version 3.0 (Varian, Palo Alto, USA). Both legs were treated with 2 isocentres, and 4 arcs per isocentre, a total of 16 arcs per fraction. Time in the treatment room was 20-25 minutes and beam-on time approximately 10 minutes each fraction. Regular weekly on-treatment reviews were set up, one with nurses and another with the prescribing RO. Weekly weighing was done to ensure adequate nutrition. Tape measurements of each leg was planned to take place every week and when necessary to document any change of circumference and therefore any change in diameter using the formula circumference / π (Pi) =Diameter; Pi value used for calculation was 3.14. Extra repeat CT scans in the planning and treatment position were to be done when necessary to document change in volumes at the 5, 10 and 15 cm marks.

Homogeneity calculation is the maximum point dose in the target divided by the reference isodose. Conformity index calculation is the volume of the structure receiving 95% dose coverage divided by the volume of the structure.

The first ten fractions were delivered. Photos were taken of the legs on the day of the 10th fraction showing little change (See figure 4). He had been applying moisturiser to his legs as instructed and was walking and swimming as usual during all this treatment time. The planned two-week break was started after fraction 10.

Figure 4A Right leg - photos taken on the day of completing 18Gy in 10 fractions showing little change except for some mild patchy erythema as denoted by the arrows. Note that there is no alopecia yet.

Figure 4B Left leg - photos taken on the day of completion of 18Gy in 10 fractions showing similar changes.

Figure 4 Photos taken on the day of completion of 18Gy in 10 fractions.

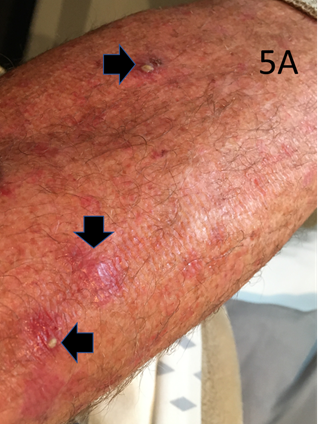

Ten days later he noticed some folliculitis but with no symptoms, with no pain and no systemic signs of infection. Examination showed mild erythema and some yellow exudate which could have been folliculitis infection or tumour necrosis.9 He was started on prophylactic flucloxacillin 500mg three times a day with good effect on symptoms. Photos were taken (See figure 5).

Figure 5A A – Left leg - distant view with horizontal arrows showing areas of folliculitis /tumour necrosis and vertical arrow showing erythema and alopecia.

Figure 5B B – Left leg - close up view with horizontal arrows showing areas of folliculitis /tumour necrosis and vertical arrow showing erythema and alopecia.

Figure 5 10 days following completing 18Gy in 10 fractions.

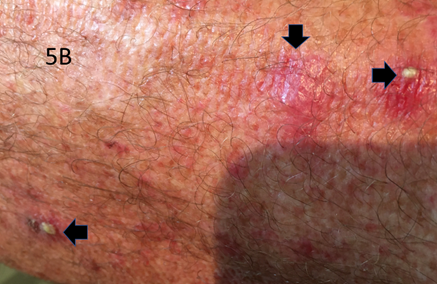

He represented for a planned restart at 16 days post the 10th fraction and had no pain. The legs were clinically swollen, and this was confirmed on tape measurement – see table 2. The RT staff noted that the bolus was not fitting as it should and surmised that this could be an early sign of lymphoedema. He had another fraction, and Cone Beam CT (CBCT) showed an increased gap in the joints of the 3DPB. A repeat CT scan was done, and on fusing the original contours, the CTV was not covering some of the anterior epidermis, a geographic miss. The posterior surface was satisfactory because presumably the gravity of the leg weight was keeping the posterior part of the CTV and PTV contours within the limb at their original position. (See figure 6). The volume changes were recorded – see table 2.

Figure 6 Rescan of Right leg at 2 weeks following completion of 18Gy in 10 fractions at 15cm proximal to medial malleolus. Compare with Figure 3A. Note swelling demonstrated by increased bolus joint width as shown by white arrows. Red arrow shows that the CTV is not covering the epidermis anteriorly, therefore causing a geographic miss. The PTV is covering more depth into the leg, especially the vascular dermis and subcutis which may set up a positive feedback loop, worsening the tendency to acute lymphoedema. The blue arrows show that posteriorly the CTV still covers the epidermis, presumably because of the weight of leg with gravity as he was treated in the supine position.

Side |

Distance |

Baseline |

16 days |

13 days |

At 39.6Gy |

40 days |

Right |

5 |

22 |

22.5 |

22 |

23 |

22.6 |

|

10 |

23 |

25 |

24 |

25 |

24.1 |

|

15 |

27.5 |

30 |

28.5 |

30 |

29.0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Left |

5 |

22 |

22.5 |

22.5 |

23.2 |

22.6 |

|

10 |

23 |

25 |

24 |

25.8 |

24.3 |

|

15 |

27.5 |

30 |

28.7 |

30.2 |

29.6 |

Pain |

|

Nil 0 |

Nil 0 |

Nil 0 |

Strong 3 |

Nil 0 |

Swelling |

|

Nil 0 |

Minimal 1 |

Moderate 2 |

Significant 3 |

Minimal 1 |

Table 2 Lower leg tape measurements over time compared with baseline and symptoms of pain and swelling. Pain and swelling ranked out of 3

Cm; centimetre, Gy; Gray, #; fractions

Another break of two weeks was advised, with a planned second rescan prior to restarting. Five days into this two-week break, he developed left groin lymphadenopathy but no had systemic signs of infection. He was started on antibiotics with resolution of the groin node. Whether this was due to infection or just continuing resolution of the swelling from the RT is unknown. He presented for continued treatment as planned two weeks later, 13 days after 19.8Gy, four weeks after fraction 10. Tape measurement and a CT rescan was done and values recorded. See tables 2 and 4. Treatment recommenced with aim of completing the whole prescription. Figure 7 shows the anti - lymphoedema garments (EasywrapTM by Haddenham Healthcare, Mount Waverley, Victoria, Australia) used. Tables 3 and 5 show the change from base line overtime in tape measurement and CT volumes at 15 cm respectively.

Side |

Base |

At 16 dys |

Diff |

At 13 dys |

Diff |

At 39.6Gy |

Diff |

40 dys |

Diff |

R |

27.5/ |

30/ |

+0.79 |

28.5/ |

0.47 |

30.0/ |

0.79 |

29/ |

0.48 |

L |

27.5/ |

30/ |

+0.79 |

28.7/ |

0.45 |

30.2 |

0.79 |

29.6/ |

0.64 |

Ave |

0 |

|

0.79 |

|

0.46 |

|

0.79 |

|

0.56 |

Table 3 Change in diameter at 15cm by tape measure– all measurements in cm

Using formula Circumference/ π (Pi) = Diameter; Pi value used is 3.14

Ave; Average, Cir; Circumference, Cm; centimetre, Dia; Diameter, Diff; difference, Dys; days, Gy; Gray, L; Left,

R; Right

Leg |

Cm above medial malleolus |

Baseline |

Rescan |

Rescan |

Rescan |

Rescan |

Right |

5 |

204.4 |

217.2 |

217.6 |

229.1 |

225.3 |

|

10 |

407.0 |

436.2 |

438.2 |

460.1 |

442.3 |

|

15 |

685.5 |

738.7 |

735.8 |

771.0 |

727.3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Left |

5 |

216.2 |

222.2 |

229.7 |

244.8 |

236.6 |

|

10 |

421.4 |

447.1 |

452.3 |

479.1 |

455.7 |

|

15 |

701 |

754.1 |

751.5 |

783.1 |

743.6 |

Table 4 Lower leg CT volume measurements over time

Cm; centimetre, cm3; cubic centimetre, Gy; Gray, #; fractions

Side |

Base |

At 16 dys |

Diff |

At 13 dys |

Diff |

At 39.6Gy |

Diff

|

40 dys |

Diff |

R |

685.5 |

738.7 |

+53.2 |

735.8 |

50.3 |

771.0 |

85.5 |

727.3 |

41.8 |

L |

701 |

754.1 |

+53.1 |

751.5 |

50.5 |

783.1 |

82.1 |

743.6 |

42.6 |

Ave |

0 |

|

53.2 |

|

50.4 |

|

83.8 |

|

42.2 |

Table 5 Change in CT volume at 15cm compared with baseline – all in cm3

Using formula Circumference/ π (Pi) =Diameter; Pi value used is 3.14

Ave; Average, Gy; Gray, #; fraction, Cir; Circumference, Cm; centimetre, Dia; Diameter, Diff; difference, L; Left,

R; Right

Figure 7G Leg and foot garment applied – anterior view.

Figure 7 Personalised flat knit compression wrap-style garments used (EasywrapTM by Haddenham Healthcare, Mount Waverley, Victoria, Australia).

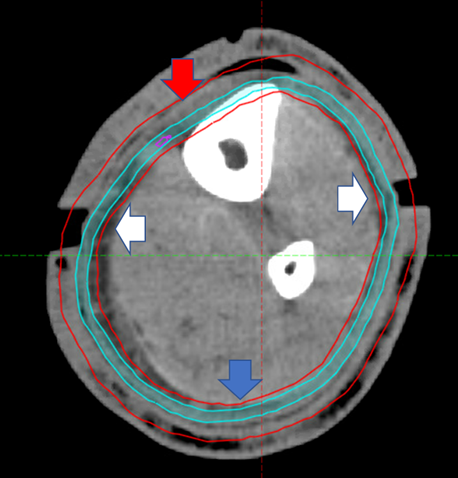

At on treatment review after 39.6 Gy in 22 fractions, the legs were again clinically swollen with erythema and now with pain despite regular paracetamol. See Figure 8. He complained that the pain was like “lava” just inside the skin of the leg, worse at the ankle posteriorly. It reminded him of the PDT. He was waking up with burning sensations in his legs and had resorted to elevation with towels soaked in cold salty water on his legs during the day. Regular thickly applied moisturiser and FlamigelTM gave symptom relief. Tape measurements were taken and a rescan organised and recorded. See tables 2 and 4. The last fraction, the 25th was cancelled. The total dose given was 43.2Gy in 24 fractions.

Figure 8D Legs after 22 fractions of RT- Posterior View. Close up.

Figure 8 Legs after 39.6 Gy in 22 fractions of RT.

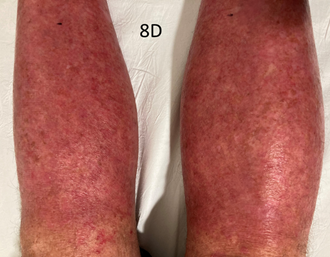

Day 6 following completion of treatment he was essentially housebound due to pain. The skin had become “flaky”. When he rose from a reclining position, he felt the “lava” type pain in his legs worse at the back of knee and ankle on the Achilles tendon, where the skin stretches more on walking. On standing the legs were sore and his feet would throb. The skin was bright red and ankles were swollen. See Figure 9.

Figure 9 Legs at Day 6 post all RT. The skin had become flaky and was bright red and ankles were swollen.

To reduce symptoms, he lay down and elevated legs above heart level and wrapped his legs in cool saline-soaked towels over both legs. Swelling was controlled with the compression garments. He preferred to keep moving rather than standing and was walking more up to 2 kilometres a day around his apartment. A prophylactic massage prior to rising from lying to standing with moisturiser and FlamigelTM decreased the intensity of pain on rising. He remained on regular Panadol and needed oxycodone 10 mg nocte to sleep at night. The “folliculitis” had returned and flucloxacillin 500mg three times a day was restarted with good effect on symptoms of yellow heads within the treatment volumes.

Day 10 following cessation of RT he noticed that the pain was getting less and he could stand for up to an hour. On day 14 he was off pain relief, there was no more ”lava” pain. From days 10-14 there was significant shedding of dead skin.

Forty days after the last fraction of RT tape measurements were taken and a rescan organised and recorded. See tables 2 and 4. The pain and swelling clinically had subsided. See Figure 10. The small, dry, scaly brown patches of DSAP had disappeared. At seventy days, there was continuing response in terms of DSAP and no pain; he said after a round of golf he said there was mild swelling which dissipated within a short time.

Figure 10D Legs at 40 days post RT - Posterior View. Close up.

Figure 10 Legs at Day 40 post RT showing resolution of DSAP.

We present a case of a fit 65-year-old male with a long history of recalcitrant DSAP treated with VMAT to the whole circumference of both lower legs simultaneously, with in-field clearance of disease at four weeks with continuing complete response at 10 weeks. This is the first publication of circumferential VMAT lower leg treatment, and of both legs simultaneously.

There is no standard treatment for DSAP, and treatment is generally not effective long-term.1,2 Symptom relieving treatments include topical imiquimod cream, topical 5-fluorouracil, and topical vitamin D analogs such as tacalcitol and calcipotriol and topical cholesterol/lovastatin10. Cryotherapy, electrodessication (using electrical currents to remove patches), laser ablation, and photodynamic therapy have also been tried.1,2,3

There are limitations and exceptions in this case:

However, the case shows that VMAT lower leg circumferential treatment is possible in select patients.

The technique of VMAT to the lower legs for ESFC continues to evolve. With this technique, there have been cases of pain, described as a burning sensation, like “lava” when the leg is moved from an elevated position to a dependent one, beginning at about 25-30 Gy. This pain is not responsive to opiates and is worse in those with a history of vascular problems especially varicosities (Brad Wong personal communication). Patients have not completed treatment due to this symptom. Incomplete treatment runs the risk of treatment failure with increased risk of infield recurrence at 12 months.5 This symptom has led to a mandated break in our national protocol7 of at least two weeks after 18-20 Gy in lower legs, and to treating one leg at a time. Other problems due to decreased dose, like keratoacanthoma,11 can also occur when treatment is not completed.

There have been learnings from this case:

This case suggests a way forward for refining our lower leg VMAT ESFC technique, especially when the PTV is large:

To reduce the chance of lymphoedema even more, active lesions requiring more dose may benefit from a review at 6 weeks following RT completion. A phase 2 electron boost to 60Gy total equivalent can then be added and may be better than a simultaneous integrated boost (SIB) in terms of lymphoedema risk. This is because the active lesion may shrink with the first course of RT, meaning the phase 2 PTV of the active lesion is smaller than that at the beginning. This is found in the adaptive split course.14,15 This means less normal tissue is involved than in using an SIB, perhaps reducing the chance of lymphoedema. It also means less dose differential which may also play a role in reducing lymphoedema.

We present a case of a fit 65-year-old male with a long history of recalcitrant DSAP treating the whole circumference of both lower legs simultaneously using VMAT with in-field clearance of disease at ten weeks. This is the first publication of circumferential VMAT lower leg treatment, and circumferential treatment of both legs with VMAT simultaneously. Despite the limitations and exceptions in this case, there were considerable learnings, and this resulted in suggesting a way forward in treating the lower legs circumferentially in select patients, especially in symptomatic recalcitrant diseases like DSAP that involve the whole lower leg circumference.

The authors would like to acknowledge the patient for allowing his case to be published; Lori Lewis of Senior Research Officer at Australian Lymphoedema Education, Research and Treatment Unit, Macquarie University, Sydney; and the staff of GenesisCare Radiation Oncology, Mater Hospital, Sydney, Australia.

None.

©2021 Fogarty, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.