International Journal of

eISSN: 2576-4454

Research Article Volume 3 Issue 4

Faculty of Marine and Fisheries, Lambung Mangkurat University, Indonesia

Correspondence: Ahmadi, Faculty of Marine and Fisheries, Lambung Mangkurat University, Jalan Achmad Yani km 36, Banjarbaru 70714, South Kalimantan, Indonesia

Received: May 17, 2019 | Published: July 29, 2019

Citation: Ahmadi. Morphometric characteristic and growth patterns of climbing perch (anabas testudineus) from sungai batang river, Indonesia. Int J Hydro.2019;3(4):270-277. DOI: 10.15406/ijh.2019.03.00189

This study provides scientific evidence on the length-weight relationship, condition factor and growth patterns of the Climbing perch (Anabas testudineus) from Sungai Batang River, Indonesia. The fish were obtained from local fishermen. A total of 156 individuals of A. testudineus consisted of 77 males and 79 females (55-125mm total length and 3-47g weight) were analyzed using SPSS-16 software. There were no statistically significance differences in the total length (TL), body depth (BD), and body weight (W) between male and female, as well as the W/TL and BD/TL ratio values of the fish (P>0.05). Most of total catch falls within the range of 80 and 89mm total length and more than 40% of total catch weighed between 10 and 19g. The W/TL ratio value of A. testudineus in the present study was more or less identical to that of A. testudineus from other different geographical areas. The fish samples were in good condition and grew negatively allometric (b=2.7766-2.8791). Outcomes of this study could be useful for fisheries management and conservation measures in this river.

Keywords: allometric, condition factor, length-weight, climbing perch, sungai batang river

Like other freshwater fish species, the Climbing perch (Anabas testudineus) belongs to family Anabantidae is also widely distributed and commercially sold particularly in Indonesia,1 Lao PDR,2 Cambodia,3 Vietnam,4 Thailand,5 Malaysia,6 the Philippines,7 Bangladesh,8 and India.9 It is rich in iron and copper, which are essentially needed for haemoglobin synthesis10 and has high quality poly-unsaturated fats and many essential amino acids. This species is locally and seasonally common throughout its range. The presence of this species beneficially supports fish farming business, however, its presence in Australia, Papua New Guinea and India, is adversely affected native freshwater and estuarine species such as birds, reptiles, animals and predatory fish due to their sharp dorsal and opercular spines.11-13 Like other labyrinth fishes i.e. Kissing gourami,14 Snakeskin gourami 15 and Snakehead,16 this species can also be cultured in the earthen pond, tanks and cages;9,17,18 It can tolerate low dissolved oxygen, low pH and temperature changes.10,19,20 Pollution, overfishing and wetland conversion may potentially threaten to this species.21

Numerous studies on A. testudineus have been dedicated to describe, for example: food and feeding habits,22-24 reproductive biology,8,25 boldness,26 growth performance and survival rate,27,28 length-weight relationship and condition factor,29,30 morphometric and meristic variation,31 water quality assessment,20 phototactic responses,32,33 conservation and aquaculture,34 and fishing activity,35-37 as well as overview of business prospect for this species.38,39 It is generally accepted that the length-weight relationship is the most common scientific approach that used for analyzing growth pattern of an individual fish species40 and advanced techniques for morphometric analysis was recently presented .41 It is also useful for understanding condition factor, survival, maturity and reproduction,7,42 of various species from different geographical regions, as well as for comparing local and interregional, morphological and life historical among species and populations.14,43

Fishing activity in Sungai Batang waters is open throughout the year regardless of seasonal periods, which is done by both villagers and beyond. The use of unfriendly fishing method (e.g. electrofishing and poisoning) is still happening beyond the control particularly during nighttime. If it is allowed without forbidden, it will adverse to fish habitat and socio-economic as the whole. To manage the Climbing perch fishery resource rationally, it is therefore needed in-depth knowledge of its biology, feeding habit and ecology. As part of the research, we started to investigate the length-weight relationship and condition factor of A. testudineus to provide some fundamental suggestions for better fisheries management.

The research was conducted in Sungai Batang River, Martapura of South Kalimantan Province (Figure 1), located on 03°22'36'' S and 114°49'29'' E, determined by GPS-60 Garmin, Taiwan. The river supports the local economic activities such as fishery, agriculture and irrigation. The village consists mostly of wetland area with water level fluctuation between 0.5 and 2m. The Climbing perch locally is called papuyu (Figure 2). For local people, it is generally accepted that the fish are quite difficult to catch during rainy season (October-April) since fish spread out in the wetland, but very easy to collect them during dry season (May-September) because they are being concentrated on the sludge holes backwater or shallow water. The fish are being caught from the swamp using lukah (fish pot), tempirai (stage-trap) and electrofishing.

Lukah is an elongated tube-shaped made of bamboo (150cm) diameter of 20cm containing one entry funnel mounted on the inside of conical-shape and tapering inside to about 2.5cm, called hinjap (one-way valve, made of elastic rattan; about 40 cm one to other), and containing one exclusion funnel at the opposite side. Thus, fish can enter easily but it is difficult to escape. Lukah are deployed in the swamp under highly vegetated habitats with slow or no current at morning and retrieved at afternoon. Lukah are submerged partly at an oblique angle of about 15º so that fish can take oxygen on the water surface. Tempirai is similar to Pengilar but bigger in the size. It is made of heart-shaped bamboo, 52cm high, 37cm width, and 5cm wide opening of the entrance slit. A small trap door on the top allowed for removal of catches. The snail (Achanita sp.) is used as bait and placed inside the trap. The trap is set in the riverbank before sunset and retrieved the next morning or mounted on a high tide and removed after low tide. The size of Tempirai is typically smaller than that of Tempirai used in Bangkau swamp. We are not able to describe the detailed electrofishing devices used in this study due to a technical barrier (unwillingness of fishermen).

A total of 156 individuals of A. testudineus comprising 77 males and 79 females were bought from local fishermen during April 2017. All fishes were individually identified for sex, and measured for total length (TL) and body depth (BD) and weight (W). Total length was taken from the tip of the snout to the extended tip of the caudal fin. Body depth was measured from the dorsal fin origin vertically to the ventral midline of the body. The total length and body depth of each individual were measured with a ruler to the nearestmm, while whole body weight was determined with a digital balance to an accuracy of 0.01 g (Dretec KS-233, Japan). The size distribution of fish sampled was set at 5-interval class for total length and weight, and was stated in percent. The length-weight relationship of fish can be expressed in either the allometric form.44

(1)

Where: W is the total weight (g), L is the total length (mm), a is the constant showing the initial growth index and b is the slope showing growth coefficient. The b exponent with a value between 2.5 and 3.5 is used to describe typical growth dimensions of relative wellbeing of fish population.45 King 46 observed that the marked variability in the value of b may reflect changes in the condition of individual related to feeding, reproductive or migratory activities. This b value has an important biological meaning; if fish retains the same shape and grows increase isometrically (b=3). When weight increases more than length (b>3), it shows positively allometric. When the length increases more than weight (b<3), it indicates negatively allometric. Isometric growth indicates that the body increases in all dimension in the same proportion of growth whereas the negative allometry indicates that the body become more rotund as it increases in length and a slimmer body.47 Determination coefficient (R2) and regression coefficient (r) of morphological variables between male and female were also computed. The condition factor of fish was estimated using the following formula.48

(2)

Where K is the Fulton’s condition factor, L is total length (cm) and W is weight (g). The factor of 100 is used to bring K close to a value of one. The metric indicates that the higher the K value the better the condition of Climbing perch. The K value is used in assessing the health condition of fish of different sex and in different seasons. In addition, the t-test was applied to compare the body sizes and condition factor between male and female. All tests were analyzed at the 0.05 level of significance using SPSS-16 software.

All estimated length-weight relationship and the ratio of body sizes of A. testudineus from Sungai Batang River are presented in Tables 1&2. A total of 156 individuals comprising 77 males and 79 females were analyzed. The body size of male ranged from 57 to 125mm (90.95±13.87mm) total length and from 5 to 47g (15.94±7.81g) weight. While the body size of female varied from 55 to 111mm (87.92±10.52mm) total length and from 3 to 26 g (14.04±4.49g) weight, with the ratio of male to female was 1:1.

Sex |

N |

Total length(mm) |

Weight(g) |

a |

b |

R2 |

r |

Growth pattern |

K |

||||

Min |

Max |

Mean±SD |

Min |

Max |

Mean±SD |

Mean±SD |

|||||||

Males |

77 |

57 |

125 |

90.95±13.87 |

5 |

47 |

15.94±7.81 |

0.00003 |

2.8791 |

0.8771 |

0.9365 |

A- |

1.99±0.30 |

Females |

79 |

55 |

111 |

87.92±10.52 |

3 |

26 |

14.04±4.49 |

0.00005 |

2.7766 |

0.8383 |

0.9156 |

A- |

2.01±0.33 |

Pooled |

156 |

55 |

125 |

89.42±12.34 |

3 |

47 |

14.97±6.40 |

0.00004 |

2.8353 |

0.8625 |

0.9287 |

A- |

2.00±0.31 |

Table 1 Total length, weight and condition factor of Climbing perch sampled from Sungai Batang River

a, constant; b, exponent; R2, determination coefficient; r, regression coefficient; A-, negative allometric; K, condition factor.

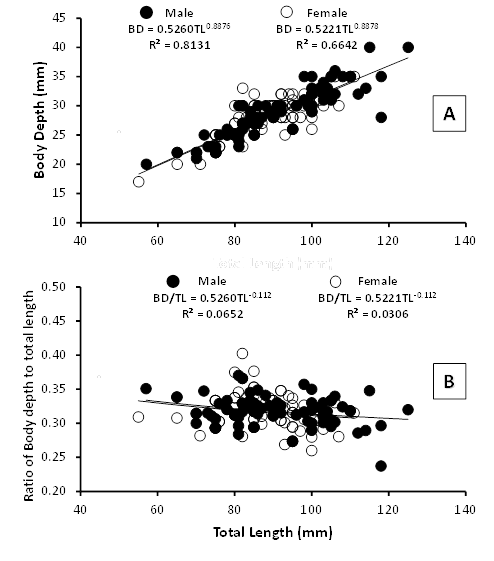

Significant differences were observed at length-weight relationship of male and female (Figure 3A), while b values implied that the body shape displays a negative allometric growth pattern (b<3), which means that the length increases more than weight. The estimated b values obtained from allometric equations were 2.8791 for male and 2.7766 for female; with the R2 values ranged from 0.8771 and 0.8383 indicating that more than 83% of variability of the weight is explained by the length. The index of correlation (r) of male and female were 0.9365 and 0.9156, found to be higher than 0.5, showing the length-weight relationship is positively correlated. Statistical analysis showed that there were no significant differences in the total length, body depth and body weight between female and male (P>0.05). It was also clearly demonstrated in Figure 3B, no statistically significant difference in the mean ratio of body weight to total length between male and female was observed (P>0.05). The ratio of W/TL for male ranged from 0.0769 to 0.3760 (0.17±0.06), while for female varied from 0.0545 to 0.2342 (0.16±0.04). As described in Table 2, the R2 values were found between 0.6798 and 0.7524 indicating that more than 67% of variability of the ratio is expounded by the length. The ‘r’ values of male and female were 0.8674 and 0.8245, found to be higher than 0.5, showing the ratio relationship is highly correlated. The increased of body depth was directly proportional to the total length (Figure 4A). The exponent values obtained from the equation curve were 0.8876 for male and 0.8878 for female. There was no significance difference in the mean ratio of body depth to total length between male and female (P>0.05) (Figure 4B). The BD/TL ratio for male ranged from 0.2373 to 0.5882 (0.32±0.02), while for female varied from 0.2600 to 0.4024 (0.32±0.04) as given in Table 2.

Figure 3 (A) Climbing perch grew negatively allometric; (B) No significant difference in the W/TL ratio values between male and female was observed.

Figure 4 (A) The body depth of Climbing perch increases proportionally to the total length; (B) No significant difference in the BD/TL ratio values between male and female was identified.

Sex |

n |

W/TL |

a |

b |

R2 |

r |

BD/TL |

a |

b |

R2 |

r |

Male |

77 |

0.12±0.02 |

0.00003 |

1.8791 |

0.7524 |

0.8674 |

0.32±0.02 |

0.526 |

-0.112 |

0.0652 |

0.2553 |

Female |

79 |

0.16±0.04 |

0.00005 |

1.7766 |

0.6798 |

0.8245 |

0.32±0.04 |

0.5221 |

-0.112 |

0.0306 |

0.1749 |

Pooled |

156 |

0.16±0.05 |

0.00004 |

1.8353 |

0.7244 |

0.8511 |

0.32±0.02 |

0.518 |

-0.11 |

0.0432 |

0.2078 |

Table 2 The ratio of body sizes of Climbing perch from Sungai Batang River

a, constant; b, exponent; R2, determination coefficient; r, regression coefficient; BD, body depth; W, body weight; TL, total length

The size distribution of A. testudineus samples in the present study is displayed in Figure 5. The highest number of catch was distributed between 80 and 84mm TL (20.78%) for male and between 85 and 89mm TL (18.99%) for female. A low number of catch was observed for larger size class more than 114mm TL. The heaviest catches of male (40.26%) and female (45.57%) weighted between 10 and 19 g. Considering the number of catch on the bar chart, the percentages of fish size distribution both length and weight was more visible in male than in female. We could find none of female catch between 30 and 49 g weight sizes. Regardless the sex, we observed that there was a difference in the exponent value for smaller length class as compared to larger ones indicating that the species has two growth levels (Figure 6). The smaller individuals (< 85mm TL) grew isometrically with the exponent being equal to the cubic value (W=0.00001TL3.0877, R2=0.9296). While the larger individuals (≥85mm TL) grew negatively allometric with the exponent lower than the cubic value (W=0.00003 TL2.9206, R2=0.9747), indicating that more than 92% of variability of the fish growth is explained by the length. Dealing with the condition factor (K) of the fish, there was no statistically significant difference in the mean K values between male and female (P>0.05) as presented in Figure 7. The mean K values obtained ranging from 0.7304 to 3.0226 (1.99±0.30) for male and from 1.1000 to 3.2646 (2.01±0.33) for female.

Figure 5 The length size (A) and weight size (B) distribution between male and female of Climbing perch taken from Sungai Batang River.

Local people in Sungai Batang village made a point of balancing between economic, social and environmental sustainability of commercially important fish species including Climbing perch fishery resource. It is quite reasonable because fish have high economic value around IDR 45,000-60,000 per kg and have good acceptance by the consumers. Like other fish species, Climbing perch is also vulnerable to destructive fishing practices. Therefore, It is categorized by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) as a vulnerable species.49 On the other word, Climbing perch formed a major part of the fish catch in the Sungai Batang River. Contrariwise, some researchers found none of Climbing perch during their sampling periods, for example in Betwa and Gomti Rivers, India.50 in the Keniam River of Taman Negara Pahang,51 in River Orogodo of Niger Delta, Nigeria,52 in Malaysian Waters,53 in Bukit Merah reservoir, Malaysia,54 in Lubuk Lampam floodplain of South Sumatera, Indonesia,55 in Shahrbijar River, Iran, 40 as well as in Narreri Lagoon of Sindh, Pakistan.43 This is likely attributable to sample size variation, typical fishing gear used, and environmental factors.

The maximum size (125mm TL) of A. testudineus in the present study was larger than A. testudineus collected from Chandpur, Matlab of Kalipur, Bangladesh: 93mm,44 but it was lower than maximum size of A. testudineus from Kausalyaganga of Orissa, India: 175mm,9 from Deepar Beel of Assam, India: 134mm,29 from Mohanpur of West Bengal, India: 170mm,56 or from a fish pond Banjarbaru of South Kalimantan, Indonesia: 170mm.57 During fishing season, it is very likely to collect A. testudineus smaller than 55mm TL and 3 g weight using the nets, but fishermen prefer release them back to the river rather than sold them with no or lower price, conversely the smaller fish might be untrappable because of fishing gear selectivity.58 The other way, it is also possible for fishermen to collect fish with the size larger than 125mm TL in the study; however, it is beyond our investigation due to the transactional selling of fish is usually occurred in early morning before the fish transported to the local market.

In the present study, A. testudineus grew negatively allometric (b<3), which is similarly documented in the previous studies.9,21,30,32,44 Our finding is contrary to A. testudineus collected from Deepar Beel of Assam, India that showed a positive allometric growth pattern.29 Dealing with variation of these growth types, some of other studies may provide much lower b values than these findings.59 The weight-length relationships are not constant over the entire year and vary according to the following factors: food availability, feeding rate, gonad development and spawning period,60,61 fecundity,56 temperature,62 salinity5 and inherited body shape.63

From the exponent values obtained, we can say that A. testudineus male (b=2.8791) grow faster than female (b=2.7766). Such growth pattern was similarly found in our previous study. 57 The exponent value (b=2.9206) for the larger individuals (85-125mm TL) was lower as compared to other fish species like M. cavasius (b=3.150) from Indus River, Pakistan observed at the maximum size of 148mm.64 It meant that such ontogenic variations in the cubic law differ from other fish species; however, a more detailed analysis regarding the reasons contributing to such variations is necessary. There was a variability of the ratios of body weight to total length among A. testudineus species from different geographical areas (Table 3). The average W/TL ratio of A. testudineus in the present study (0.167) was relatively higher than that of A. testudineus from Deepar Beel of Assam, India: 0.162,29 from Chandpur, Matlab of Kalipur, India: 0.06944 or from Tetulia River, Bangladesh: 0.083.21 However, this ratio was considerably lower as compared to those sampled from Kausalyaganga of Orissa, India: 0.390,9 from Kuttanad of Kerala, India: 0.363,30 or from Mohanpur of West Bengal, India: 0.353mm.56

The average K value obtained (2.00) for A. testudineus in the present study (Table 3)was slightly lower than that of A. testudineus from Kuttanad of Kerala, India: 2.0630 or from Kausalyaganga of Orissa, India: 2.07.9 Barnham & Baxter 65 suggested that if the K value is 1.00, the condition of the fish is poor, long and thin. A 1.20 value of K indicates that the fish is of moderate condition and acceptable to many anglers. A good and well-proportioned fish would have a K value that is approximately 1.40. Based on this criterion, the Climbing perch from Sungai Batang River were in good condition although fish grew negatively allometric. Regardless the sex, Bagenal & Tesch66 documented the K value between 2.9 and 4.8 for mature freshwater fish species; meanwhile the K values in the current study ranged from 0.7304 to 3.2646, indicating that some of individual fish are being mature when captured. Variation in the value of the mean K may be attributed to biological interaction involving intraspecific competition for food and space between species including sex, stages of maturity, state of stomach contents and availability of food,50,66 as well as season and other environmental conditions.67

Locations |

Country |

n |

W/TL |

a |

b |

R2 |

r |

Growth pattern |

Average |

References |

Sungai Batang River |

Indonesia |

156 |

0.167 |

0.00004 |

2.8353 |

0.8625 |

0.9287 |

A- |

2.000 |

Present study |

Banjarbaru, South Kalimantan |

Indonesia |

608 |

0.216 |

0.0005 |

1.8049 |

0.4339 |

0.6587 |

A- |

2.115 |

Ahmadi (2018b)57 |

Kuttanad, |

India |

246 |

0.363 |

0.0003 |

2.8452 |

0.9556 |

0.9775 |

A- |

2.060 |

Kumary and Raj (2016)30 |

Mohanpur, Nadia District |

India |

30 |

0.353 |

-2.025 |

2.316 |

0.5396 |

0.7346 |

A- |

- |

Ziauddin et al. (2016)56 |

Kausalyaganga, Orissa |

India |

544 |

0.390 |

-1.432 |

2.7201 |

0.0821 |

0.9264 |

A- |

2.070 |

Kumar et al. (2013)9 |

Deepar Beel, Assam |

India |

120 |

0.162 |

-2.540 |

3.645 |

0.8500 |

0.9220 |

A+ |

1.000 |

Rahman et al. (2015)29 |

Chandpur, Matlab, Kalipur |

Bangladesh |

73 |

0.069 |

-1.518 |

2.423 |

0.9660 |

0.9828 |

A- |

1.085 |

Begum and Minar (2012)44 |

Tetulia River |

Bangladesh |

176 |

0.083 |

0.0220 |

2.90 |

0.9740 |

0.9869 |

A- |

- |

Hossain et al. (2015)21 |

Table 3 Comparative parameters of length-weight relationships and growth patterns of Climbing perch from different geographical areas

a, constant; b, exponent; R2, determination coefficient; r, regression coefficient; A, allometric; K, condition factor.

In the investigated area, local fishermen mostly used lukah (fish pot), tempirai (stage-trap) and also electrofishing for catching A. testudineus from its natural habitats, while other workers used the seine nets in the cultured ponds, Bangladesh,11 fish nets in local ditches in Adra Purulia, West Bengal India,23 gillnets in flood plain swamp, South Sumatera Province or in Batang Kerang Floodplain, Balai Ringin, Sarawak,68,69 Khepla Jal (cast net) in the Chalan Beel, Bangladesh,70 tampirai (wire stage-trap) in Sebangau River, Central Kalimantan Province, 71 a conical trap in the ponds, West Bengal India,24 lalangit (horizontal set gillnet) in Bangkau swamp, South Kalimantan Province,36 pukot and electrofishing in floodplain Lakes of Agusan Marsh, Philippines,72 light traps in the cultured ponds, South Kalimantan Province.32,33 According to Aminah & Ahmadi,37 the catchability of the gear is higher during the dry season compared to the wet season, because the fish are being concentrated on the sludge holes or shallow areas and allow for catching them easily. While Kamaruddin et al.73 found the opposite condition, with the reason is the wet season indicates the main feeding and growing time for the fish,52 and it is very likely to catch the fish. In addition, female climbing perch showed a marked increase in their food intake early in the wet season.7 Variation in the catches may be attributed to the catchability of the gears, species target, fishing ground characteristic, fishing operation, and the abundance of the fish in that area.70,74 There are three main constraints being faced in this area of study: the first, there is no daily record for A. testudineus catch in quantity (e.g. number, length and weight) because fishes are directly sold to traders or consumers in some places; secondly, fishing activity is on-going throughout the year regardless of seasonal periods, thus resulted in the ratio of the fish exploitation rate to the fish growth rate in this river is still unpredictable; and the thirdly, the use of electrofishing is still beyond the control because it is usually undertaken at the night. So, it is a great challenge for Marine and Fisheries Services of Banjar District to improve the quality of inland fishery statistical data and manage the fishery resources through EAFM program.

The climbing perchsampled from Sungai Batang River were in good condition and grew negatively allometric. The scientific information on the length-weight relationship and condition factor of climbing perch could be used to estimate the stock population and to take conservation measures.

None.

The authors declares that there are no conflicts of interest

©2019 Ahmadi.. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.