International Journal of

eISSN: 2574-9862

Mini Review Volume 6 Issue 1

1Department of Nutrition and Animal Husbandry, University of Veterinary Medicine and Pharmacy, Košice, Slovakia

2Department of Biology and Physiology, University of Veterinary Medicine and Pharmacy, Košice, Slovakia

Correspondence: František Zigo, University of Veterinary Medicine and Pharmacy, Department of Nutrition and Animal Husbandry, Košice, Komenského 73, 040 01, Slovakia

Received: August 30, 2022 | Published: September 23, 2022

Citation: Zigo F, Ondrašovičová S, Farkašová Z. Correct interpretation of carrier pigeon diseases - Collibacillosis. Int J Avian & Wildlife Biol. 2022;6(1):27-30. DOI: 10.15406/ijawb.2022.06.00180

Despite the breeder's efforts to minimize stress factors during the racing season, disease can occur even in the best lofts. Among the specific diseases caused by high performance, immunosuppression of the organism, imbalance of gastrointestinal micro flora of carrier pigeons and non-observance of hygienic conditions is included collibacillosis. Collibacillosis is localized or systemic infection caused entirely or partly by avian pathogenic Escherichia coli (APEC). Although some strains of APEC cannot cause disease by themselves, their pathogenic lifestyle, suggesting that infections might always be opportunistic or secondary to some most frequently predisposing diseases such as coccidiosis, adenovirosis, canker, intestinal worms and others. The disease causes reduction in performance or loss of infected pigeons, vomiting, diarrhoea, enteritis, dehydration, depressed feed intake or decreased growth rate in young pigeons. An outbreak of collibacillosis during the racing season is often the result of a combination of several factors that cannot be completely eliminated. It is therefore useful to develop a prophylactic plan in which the breeder focuses not only on the elimination of the main predisposing diseases, but also notices the factors that can stress the pigeons and thus cause an outbreak of APEC.

Keywords: avian pathogens, Escherichia coli, gut microflora, environment

Pigeon races are among the greatest experiences for breeders, but they also bring many stressful factors that affect the health and performance of these noble birds. Based on experience and clinical manifestations, breeders encounter the occurrence of the four most common problems causes of diseases such as coccidiosis or combination with pathogenic avian E. coli (APEC) and intestinal worms, trichomoniasis or canker, ornithosis complex and viral diseases that most commonly affect pigeons.1

Especially in recent years there has been a lot of talk in the pigeon world about APEC bacteria that causes a disease called collibacillosis. E. coli is one of the most widespread organisms on the surface of the planet. There are many different strains (or serotypes) of E. coli. These serotypes differ in their virulence factors and ability to cause disease. It is known that the avian collibacillosis is a secondary disease and APEC are opportunistic to some most frequently predisposing conditions. However, increasing evidence indicates that most APEC are well equipped for a pathogenic lifestyle and infections might not always be opportunistic.2

Mainly APEC causes diverse local and systemic infections in poultry, including chickens, turkeys, ducks, and many other avian species. The most common infections caused by APEC in avian species are enteritis, perihepatitis, airsacculitis, pericarditis, egg peritonitis, salphingitis, coligranuloma, omphalitis, cellulitis, and arthritis. APEC also causes swollen head syndrome in chickens and osteomyelitis complex in turkeys.3 Collibacillosis is one of the leading causes of mortality (up to 20%) and morbidity in poultry and also results in decreased meat (2% decline in live weight, 2.7% deterioration in feed conversion ratio) and egg production (up to 20%), decreased hatching rates, and increased condemnation of carcasses (up to 43%) at slaughter. Furthermore, APEC is responsible for high mortality (up to 53.5%) in young chickens.4

The big problem with APEC and pigeons is the interpretation; that is, how to interpret the finding of the presence of E. coli.5,6 This is because E. coli is normally inhabits the intestinal tract of all animals and birds. There are a number of different strains and many are species-specific. Bacteria E. coli can be found in most normal and healthy pigeons which were confirmed from our previous study. Swabs from the cloaca of 60 carrier pigeons confirmed E. coli in 93% of samples during racing season without symptoms of another clinical disease.7

If E. coli is identified in other parts of the body than in the gut, including the colon, then this indicates potential health problem that usually requires treatment. E. coli is sometimes identified in the crop. It is not a normal resident of the crop, which is why it is unusual there. The probable cause usually falls into one of the following four categories:

The identification of E. coli outside the gut means that the bacteria have penetrated the gut wall and have been carried by the blood to another location. In this way, APEC can infect the liver, heart, kidneys or other organs. In this situation, antibiotic treatment is indicated. When APEC invades the body from the gut, it always causes disease. This means that if APEC is found anywhere else in the body besides the gut, then it is definitely a problem. The problem arises if it is present only in the intestine. If the APEC strains in the gut are capable of causing disease, it causes enteritis. Enteritis is an inflammation of the intestinal wall. With pathogenic strains, this inflammation can be severe, leading to fluid loss and indigestion. This in turn leads to green watery droppings and an obviously sick pigeon. With mild strains, the inflammation is often also mild and the changes in the decline are less pronounced. The droppings may remain shaped but be slightly green, or have slightly increased water content, resulting in the white component of the droppings being blurred rather than sitting distinctly and separately (Figure 1). Likewise, signs of poor health shown by a pigeon can be subtle and non-specific, such as stopping the shedding the down coat or reducing the time the pigeons voluntarily spend on the wings.9,10

Figure 1 Possible causes of changes in dropping appearances in pigeons Source: Scullion and Scullion.10

Some disease-causing strains can cause disease in even the strongest pigeons. Many strains of APEC in pigeons are simply opportunistic, waiting to cause disease if something stresses the birds. It can be a persistent environmental or breeding problem, or another concurrent disease. In particular, APEC is often involved as a secondary agent with viral problems, especially adenoviruses (young pigeon disease).10

The European breeders are well aware of the fact that adenovirus infection in pigeons represents a significant problem. A combined adenovirus and APEC infection has been identified and is called the adeno-coli syndrome. In the absence of a bacterial infection, this type of adenovirus causes little or no problem. Because adenovirus damages the lining of the intestinal tract, APEC can invade and cause disease. Thus, controlling APEC with antibiotics may significantly reduce the symptoms of adenovirus infection.6 Probably one of the reasons why APEC is such a common secondary invader is that it is present much more frequently. There are other bacteria that can also be opportunistic, but they usually are not. If they were present when the pigeon was exhausted or stressed, they could also cause disease.9

One of the problems of misinterpretation is that in case of bacterial intestinal diseases the bacteria are often identified by culture. This is where the organism is actively cultivated in the laboratory.8 Samples should be streaked on EMB agar, MacConkey, or tergitol‐7 agar, as well as non-inhibitory media. A presumptive diagnosis of E. coli infection can be made if most of the colonies are characteristically dark with a metallic sheen on EMB agar, bright pink, with precipitate surrounding colonies on MacConkey agar, or yellow on tergitol‐7 agar. Strains of E. coli can be slow or non-lactose fermenters and appear as non-lactose‐fermenting colonies. Definitive identification of E. coli is based on the organism’s characteristics. A flow chart for the isolation and identification of E. coli has been published. A number of manual and automated systems are available for identification of bacteria, including APEC.11

In addition to culturing samples for the presence of E. coli growth, it is recommended to spread the sample on other selective agars for the identification of salmonellosis, streptococci and staphylococci. The problem arises in the fact that E. coli is very easy to grow, while other organisms that can cause similar symptoms, such as salmonella, can be quite difficult to grow. This means that sometimes E. coli is blamed as the cause of the problem when in fact another culture that is more difficult to cultivate is overlooked.8

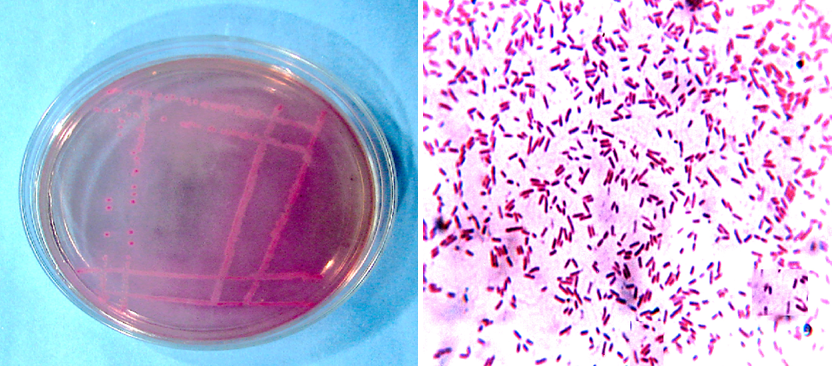

Diagnosis can be even more difficult or impossible when faeces are simply examined under a microscope as a faecal smear. Bacteria come in two common shapes, dots (called cocci) or short lines (called rods or bacilli). Different types of bacteria differ not only in their shape, but also in size, ability to move and other characteristics. E. coli are medium-sized rods that are often motile (able to move) (Figure 2). Some types are not. Dots are mostly normal bacteria called enteric streptococci (or enterococci). Many of the rod-shaped bacteria are also harmless, and in fact some are beneficial, for example lactobacilli.12,13

Figure 2 Cultivation and identification E. coli from cloacal swabs from left: E. coli isolates showing rose pink colored colonies on MacConkey agar. Isolated E. coli in Gram’s straining (microscopic) showing Gram negative, pink color, short rod shape organisms, arranged in single or paired. Source: Tonu et al.12

For those with a microscope, it's easy to be mystified by the various shapes, sizes, and movements when examining a faecal smear at 400x magnification. Under normal circumstances, a mixture of bacteria is present with a predominance of dot-shaped bacteria. If many intermediate motile rods are present, it may be E. coli. If there are many dots for each short moving rod, then everything is probably fine. When the number of motile rods increases and certainly when these become the predominant bacterial organisms, it is best to get a veterinarian to check the pigeons. However, what is visible under the microscope must always be related to what the pigeons are doing; that is, how they appear and communicate with each other and how their droppings look.8

Although some strains of APEC can cause disease by themselves, usually their ability to cause disease is secondary. The breeder should start treatment only if clinical symptoms are present in several pigeons. Treatment must always be based on the sensitivity of cultured E. coli to antibiotics. This is critical as E. coli varies tremendously as to which antibiotic kill it. It develops resistance very quickly to antibiotics and breeder should never assume that what worked one time will work the next time. Generally the treatment of collibacillosis involves three areas:

Management practices designed to minimize the exposure level of these types of organisms in the bird’s environment are necessary in any preventive program. Avoiding overcrowding and providing proper ventilation along with good biosecurity, and appropriate sanitation and hygiene standards are in general highly effective measures in the control of collibacillosis in pigeons’ lofts, and thereby reducing its zoonotic incidences.2

A specific situation occurs during the racing season when the approach to the detection and treatment of diseases in pigeons is different.15 Detecting a high level of E. coli in the droppings, even in pigeons that look good, indicates general immunosuppression. Although APEC bacteria may not have started the problem, they will become part of it. In a mild outbreak, correcting the primary problem will improve the health of pigeons and also resolve the APEC problem. In case of more severe outbreaks, in addition to correcting the primary problem, treatment for collibacillosis may be necessary to return the pigeons to their original good form.6

The following approach is common:

Outbreaks of collibacillosis are often associated with some kind of stress during racing season. There is always the possibility that a pathogenic strain could be introduced into the loft through the racing or by foreign or lost pigeons. However, this does not usually happen. The breeder's first thought should be that this is probably a secondary problem. The breeder should therefore think about what has happened in the loft recently and look for the cause of the appearance of APEC. It is helpful to develop a checklist to note factors that may have stressed the pigeons and caused the APEC outbreak.

The reasons will vary from loft to loft, so the answer for each breeder will be different. In some lofts where APEC is not usually present, its discovery may indicate a management error or recent moulting, etc. The answer is often obvious. In cold-sensitive lofts (i.e. open) the problem may be intermittent and correlated with weather changes. Changing the design of the loft may be the answer here. In some lofts it can be a good indicator of another disease; for example coccidiosis or canker, so in pigeons with a known medical record of collibacillosis can be used to monitor the treatment and manage other problems.

In one loft it may be recommended to reduce the workload of the pigeons and increase the energy content of the pigeon feed either by changing the grain mix or by using specific energy supplements, such as a seed oil supplement. In another loft, it may be recommended to administer medicines for two days, followed by some multivitamins. So there are many correct answers to solving one problem, and the answer not necessarily results in a cure. If the stressor cannot be identified, APEC will respond poorly to any drug or reappear after the drug is stopped. On the other hand, if the stressor can be quickly identified and corrected, then the boost the pigeons receive in overall health will often allow the pigeons to rid themselves of APEC on their own.

The study was support by grant KEGA 009UVLF-4/2021: Innovation and implementation of new knowledge of scientific research and breeding practice to improve the teaching of foreign students in the subject of Animal husbandry.

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

©2022 Zigo, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.