eISSN: 2576-4470

Research Article Volume 8 Issue 2

1Doctor in Social Sciences, Autonomous University of the State of Mexico, Mexico

2Doctor in Public Administration, Autonomous University of the State of Mexico, Mexico

3Doctor in Urban Planning, Autonomous University of the State of Mexico, Mexico

Correspondence: Pedro Leobardo Jiménez Sánchez, Doctor in Social Sciences; Research Professor at the Autonomous University of the State of Mexico, Mexico

Received: April 05, 2024 | Published: April 18, 2024

Citation: Sánchez PLJ, Ferrusca FJR, Alanís HC. Social mechanisms for the development of irregular human settlements in Chetumal, Quintana Roo, Mexico. Sociol Int J. 2024;8(2):98‒102. DOI: 10.15406/sij.2024.08.00381

The work presents partial results of a research carried out by the Autonomous University of the State of Mexico, oriented to the analysis of urban growth that develops on the periphery of cities through informal and illegal land occupation processes. The analysis aims to address the social practices and mechanisms that the population exercises to satisfy their land and housing needs, taking the city of Chetumal, Quintana Roo, Mexico as a case study. The results show that the State and real estate developers express their interest in developing the city in a formal way, in which they satisfy the needs of the population with high economic resources and leave aside the poorest population, who practice social actions for the development of irregular human settlements.

Keywords: urban periphery, informal growth, social needs, illegal occupation

The city of Chetumal is located in the municipality of Othón P. Blanco, having an important political representation as it is the capital of the State of Quintana Roo, concentrating the structure of the state public administration. Being a coastal city, founded on a bay, Chetumal enjoys natural maritime privileges and great tourism potential; however, its economic activities are more oriented toward satisfying the demands and needs of the population that works in government agencies. In this regard, one of the primary needs that has been had is the satisfaction of housing needs, where the State and private initiative have intervened to provide housing to the population with high economic resources. Although the growth of the City of Chetumal during the last part of the last century was characterized by moderate natural and social growth, it was not until nearly three decades ago that it had accelerated population growth and, consequently, housing needs of the native and migrant population from other parts of the State and the country. The result has been an increase in the population's needs for land and housing, whose ways of satisfying and finding a place to live, constitutes the search for peripheral areas of the city, in search of cheap and accessible land economic situation of the population, many times in areas and zones not suitable for urban development.

Trinidad,1points out that a characteristic of the production of Latin American cities has been the result of the functioning and conjunction of three logics of social coordination: the market, the State and the logic of necessity, the latter being constituted by a set of individual and collective actions that promote the production of what must be called “popular cities”; This form of urban production, according to Abramo,2 has developed from a modality of access to habitat, characterized by its usual process of occupation/self-construction/ self-urbanization and consolidation; This modality of production of the popular city is presented as a new variant that articulates the logic of the market with that of need, and manifests itself socially as the informal land market. One of the fundamental causes that motivates the low-income population to look for peripheral areas to settle is the lack of housing programs for the low-income population; Although there are official programs, these are intended or reserved for the population that has the purchasing power to cover the costs of these formal housing actions.

On the other hand, the population that lacks the resources to access these official programs seeks, through informality and the development of irregular human settlements, to satisfy their housing needs. According to Cabrera,3 the growth of informal settlements is a direct consequence of the impossibility of formal access to land for a large percentage of the population. Accessing the formal housing market means paying high rents, or being subject to mortgage credit required by real estate companies. Thus, their only alternatives are taking land and self-construction, or joining the informal real estate market. Another cause of informality, according to Rojas,4 is attributed to regulatory frameworks that are far from social needs, which, far from solving, has contributed to the expansion of informality, although they have recently been subject to review, improvement and updating. Urban planning legislation itself was, and in many cases continues to be, the subject of criticism. Bentes,5 points out that urban planning legislation, because it is inadequate to the needs of the real city and society, is not complied with both by the poor (invading land or buying it in subdivisions outside the norms) and by the rich (building more than what building regulations allow or occupying land not designated for urban uses), which in the long run leads to results opposite to its initial purpose of establishing optimal conditions for the occupation of urban space. In this way, informality develops regularly in cities through the process of occupying land outside the norms established in legal and planning instruments, where the actions of society are those that support the process through practices and social mechanisms that determine the growth of the urban sprawl on the periphery of cities and, particularly, lacking the minimum necessary satisfiers: infrastructure, public services, equipment and legal insecurity of property.

The method used to carry out this work is based on the Mixed research method, which involves qualitative and quantitative methods,6 The analysis is based on the deductive method with a systemic vision, which consists of the formulation of the theoretical foundation of the study phenomenon and the construction of the methodological variables to apply it to a case study. In this regard, the variables identified refer to three, fundamentally:

The research responds to a geographical study, highlighting that there has been direct contact with the real problem, based on participant observation and that, taking into consideration the guidelines of Gutiérrez and Delgado,7 It has been practiced in visits to irregular human settlements where the study phenomenon takes place, which has made it possible to visualize and record spatial and social events, arguing for the production of knowledge and the generation of potential solutions.8 The case study technique, based on the study of the irregular human settlements that have developed on the outskirts of the city of Chetumal, allows collecting information in the different study areas and, in this way, having a more objective panorama of what was analyzed.

The urban growth of Chetumal

The city of Chetumal is located in the southeastern portion of the Yucatan Peninsula, whose quantification of its urban area for the year 2011, constitutes an approximate surface of 3,170.38 hectares,9 in which approximately 151,243 inhabitants live,10 incorporating it as the second city with the largest number of inhabitants in the state of Quintana Roo. This urban area is the result of its location, whose foundation next to the Bay corresponds to an urban center that is not the geometric center, but rather its growth has developed radially towards the north, northeast, northwest and west, whose antecedents and Analysis of its urban growth reveals four forms of development of the urban area:

According to the purposes of this work, it is in this last modality that the results of this research rest, in which the actions and social practices that the population uses to develop irregular human settlements in Chetumal are analyzed.

Characterization of irregular human settlements in Chetumal

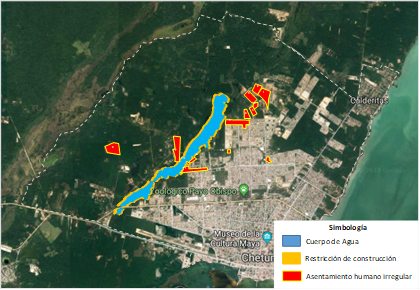

According to the Urban Development Program of Chetumal-Calderitas-Subteniente López- Huay - Pix and Xul-Há. Municipality of Othón P. Blanco, State of Quintana Roo,9 in the peripheral areas of the urban center of Chetumal, 14 irregular human settlements were identified (Table 1), which have been developed based on the needs housing areas of the population, who have searched on the periphery of the city (Figure 1) for a place to live, all of them formed through a process of informal occupation of the land, comprehensively occupying a total of 110.20 hectares, which in their Together they house approximately 5,640 inhabitants.

|

No. |

Name |

Surface |

|

1 |

The Eden, |

8.80 hectares |

|

2 |

Saint Fatima, |

6.90 hectares |

|

3 |

Kettles 1, |

11.80 hectares |

|

4 |

Calderitas 2, |

6.50 hectares |

|

5 |

Pigeons,) |

5.20 hectares |

|

6 |

Cordoba, |

3.90 hectares |

|

7 |

The triumph, |

9.30 has |

|

8 |

Fraternity, |

7.80 hectares |

|

9 |

The fringe, |

10.00 hectares |

|

10 |

Holy Spirit, |

2.00 hectares |

|

11 |

New Progress, |

19.50 hectares |

|

12 |

Tamalcab , |

11.00 has |

|

13 |

Bordo La Sabana |

1.00 hectares |

|

14 |

CTM Cologne |

6.50 hectares |

|

Total you have |

110.20 hectares |

Table 1 Irregular human settlements in Chetumal, 2014

Source: Own elaboration based on SEDATU-GM, 2014.

Figure 1 Location of irregular human settlements in Chetumal.

Source: Own elaboration based on Google Maps (2021) and SEDATU-GM, 2014.

One of the characteristics presented by the 14 irregular human settlements is the process of occupying the land to satisfy the needs of the population to live; Derived from the above, the analysis shows that of the 14 irregular human settlements, 10 irregular human settlements are located on lands of the ejidal nuclei of Chetumal and Calderitas, with an area of 72.5 hectares; For their part, 4 of them are located on privately owned lands, occupying an area of 38 hectares.

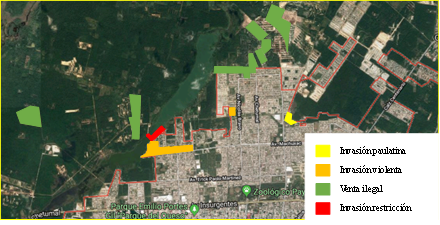

It should be noted that within the vicinity where some irregular human settlements have settled, there is an important water element known as “La Sábana”, which is being affected in two ways: on the one hand, it is observed that the irregular human settlements called Nuevo Progreso, Tamalcab and La Sabana are located on the edge of the body of water, known as wetlands; On the other hand, according to the regulations established by federal regulations, the three irregular human settlements are located on the construction restriction areas established on the edge of the body of water (Figure 2). This situation not only affects the body of water, but also puts the inhabitants of the homes at risk by occupying the indicated construction restriction areas.

Figure 2 La Sabana body of water, affected by irregular human settlements.

Source: Own elaboration based on Google Maps (2021) and SEDATU-GM, 2014.

Mechanisms and social practices in the development of irregular human settlements

The social practices that have been identified in the development of the 14 irregular human settlements are manifested through a process through which physical-artificial objects are produced aimed at satisfying the collective needs of society and that are developed by the own society with its own means and resources, in a precarious way, outside of all urban regulations and without any order. The 14 irregular human settlements located in the study area make up an area of 110.50 hectares, they originated in accordance with the procedures and processes indicated in Table 2.

|

No. |

Name |

Social practice |

|

1 |

The Eden |

Settlement located in areas of common use and was promoted by ejidatarios of Calderitas. |

|

2 |

Saint Fatima |

Settlement located in areas of common use and was promoted by ejidatarios of Calderitas |

|

3 |

Cauldrons 1 |

Settlement located in areas of common use and was promoted by ejidatarios of Calderitas |

|

4 |

Cauldrons 2 |

Settlement located in areas of common use and was promoted by ejidatarios of Calderitas |

|

5 |

pigeons |

The settlement was promoted by ejidatarios from Calderitas; Its legal situation is in a stage of “stagnation”, since the agrarian process continues its course before the federal authorities. |

|

6 |

Cordoba |

Settlement promoted by ejidatarios on plots of the Calderitas ejido. |

|

7 |

The triumph |

Settlement promoted by ejidatarios, located on common use lands of the Ejido Calderitas. |

|

8 |

Fraternity or Gaucho |

Settlement promoted by ejidatarios, located on ejidal lands without a specific land use assignment. |

|

9 |

The fringe |

Settlement promoted by ejidatarios, originated by the ejidatarios' claim derived from the expropriation of the Ejido Chetumal. |

|

10 |

Holy Spirit |

Settlement that has its origin in a process of invasion and sale of lots |

|

11 |

New Progress |

Settlement promoted by ejidatarios, located on lands of the Calderitas ejido core and developed on natural areas. |

|

12 |

Tamalcab |

It is a settlement derived from an expropriation for the expansion of the Calderitas ejido, promoted by the ejidatarios. |

|

13 |

Savannah |

Settlement developed through a process of “ant filling”, invading the restriction strip of the La Sabana water body. |

|

14 |

CTM Cologne |

Settlement developed through the invasion and sale of lots; the original project of the subdivision was not respected in its entirety; There are problems of invasion of boundaries with neighboring properties. |

Table 2 Social practices in the development of irregular human settlements

Source: Own elaboration based on SEDATU-GM, 2014.

According to Rueda,11 Del Soto,12 the Ministry of Social Development,13 and Jiménez,14 in the formation of the 14 human settlements identified in Chetumal, two types of illegal occupation processes are identified. land: invasion and illegal sale, which are manifested in four social mechanisms: gradual invasion, violent invasion, illegal sale and restriction invasion, which have constituted social processes, in which agents and actors intervene directly involved social; Thus, the distribution of human settlements in each of these mechanisms is presented as follows (Table 3 & Figure 3):

|

Occupation mechanism |

Name |

|

Gradual invasion |

CTM Cologne |

|

Violent invasion |

Holy Spirit |

|

New Progress |

|

|

Illegal sale |

The Eden |

|

Saint Fatima |

|

|

Cauldrons |

|

|

Cauldrons |

|

|

pigeons |

|

|

Cordoba |

|

|

The virtue |

|

|

Fraternity or Gaucho |

|

|

The fringe |

|

|

Restriction Invasion |

Savannah |

|

Tamalcab |

Table 3 Occupation mechanisms of irregular human settlements

Source: Own elaboration based on Table 2.

Figure 3 Irregular human settlements by land occupation mechanism.

Source: Own elaboration based on Rueda (1999), Del Soto (1979), Secretariat of Social Development (2010) and Jiménez (2019) and Google Maps (2021).

As can be seen, in the process of occupying the land for the development of irregular human settlements in Chetumal, it has been based on the needs of the population to have a piece of land on which to build their home. The analysis shows that the main form of development is through the organization of the ejidatarios themselves to develop the practice of illegal sale of their lands; On the other hand, the organization of the population, which, through violent invasion, satisfies its needs for land and housing.

Final comments

In this research work, the process of informal urban growth of the peripheral areas of the City of Chetumal, Quintana Roo, Mexico was analyzed, whose informal actions are oriented to the process of land occupation in areas not established in urban development plans such as developable; On the contrary, the informal growth of peripheral areas is presented as a new form of urban growth and urbanization that is characterized by being slow and complex, as the inhabitants themselves are the ones who, with their own means and resources, satisfy their land and land needs living place. The study shows that the fundamental cause of the occupation of the periphery to develop informal growth is the lack of housing programs aimed at the population with low economic resources or who have the need to obtain a place to live; the result is the search for cheap land that is accessible to their economic capacity and housing needs. In this way, it is observed that, in this informal process, it is a product of the relationship that the State and private initiative have in satisfying the housing needs of the wealthiest population and leaving aside the poorest populations.

The process of informal urban growth on the outskirts of Chetumal has caused the formation of 14 irregular human settlements, which in the last 30 years have proliferated gradually and permanently, being a common social practice among the population seeking housing, in which process is the same population who satisfies their housing needs through their own means and resources; In your case, there is an absence of infrastructure and basic municipal services:

The analysis carried out in this article shows that the State, far from satisfying the demand of the most needy population in terms of housing, is what causes informal urban growth on the periphery of cities. Due to the lack of housing programs, the population seeks places to live, through the formation of irregular human settlements in areas not specified by the municipal urban development plans for formal urban growth. This situation is more complex when the participation of private initiative in the promotion and production of housing development actions through formal subdivisions determines that access to this type of housing is only offered and accessible to the population with high economic resources.

In this way, the population that cannot access housing actions through formal housing programs seeks to satisfy its land and housing needs in peripheral areas of cities, joining the informal and illegal land market of lands not specified as developable. or, where appropriate, not suitable for urban development. The problem worsens when the irregular human settlements that are formed through this mechanism lack interest on the part of the State or local authorities to provide them with infrastructure, public services and/or equipment.

The incorporation of the population into the informal land market has been seen as one of the most viable alternatives to obtain a piece of land on which to build their home, on land of social origin, in which costs have been lower than in the formal land market; In this sense, there is also a preference to obtain a piece of land on ejidal lands, since it is the members or representatives of the ejidal nuclei themselves who promote the sale of the land at prices accessible to the needy population.

Likewise, the mechanisms of land occupation, of course, present alternatives to access the informal and illegal land market; Thus, the violent invasion, the gradual invasion, the illegal sale and the invasion of construction restrictions are a clear example that the social needs of the population are above the urban regulations and legislation imposed by the State.

In the case of Chetumal, social practices, therefore, have been an alternative that the population uses to have access to land and housing through processes of informal land production on the periphery of cities, in which only population native to the municipality but also migrant population from the entity and other parts of the country. Without a doubt, an important aspect in this process is the attractiveness of these types of coastal cities that provide opportunities for a place to live, followed by sources of work in economic activities and related to public administration.

Derived from the results of the study, the formation of an interdisciplinary group of researchers is observed, which is incorporated from different areas to analyze this type of problems related to the territory and the basic needs of the population, such as access to land and housing. This interdisciplinarity in this type of research, referring to the case study analyzed, shows that science encompasses different ways of analyzing the territory from the points of view of planning and geography. Although the results presented in this article are due to a partial work of a more in-depth investigation, we can point out that the results will allow a diversity of pending topics that can be taken up by other disciplines and other groups of researchers. In this way, informal growth on the periphery of cities turns out to be a current issue, being referred to by some authors as new forms of urbanization. An important line of research, identified in the work, is the importance that the lands currently have, belonging to the ejidal nuclei in the country, which, as can be seen in the work, not only because they are the most susceptible to occupation through the mechanisms informal and illegal, but are the only areas that currently present the conditions to be regularized and/or expropriated by the State.

However, the complex process required by such legal procedures determines uncertainty on the part of its occupants as they do not have legal security of their property. The crucial question that arises from this research, and that perhaps is one more line of research for future research, is the responsibility that the authorities have not only in the process of regularization of land tenure or the legal security of property. , but also the interest of the State and local authorities to provide these irregular human settlements with infrastructure and basic services or equipment that satisfy their present and future needs.

Finally, it is clear that although the State, in some way, is the cause of this informality, by not allocating housing programs for the population with low economic resources or who, where appropriate, work in informal economic activities, it forces us to think that it is not would be interested in the development of policies or actions to satisfy the housing needs of this population, much less allocate a budget according to these new forms of urban growth, which ensure urbanization appropriate to the housing and social reality of the cities.

None.

None.

©2024 Sánchez, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.