eISSN: 2576-4470

Review Article Volume 9 Issue 5

1University of British Columbia, USA

2Founder & Director, Utilization-Focused Evaluation, USA

Correspondence: Michael Quinn Patton, Founder & Director, Utilization-Focused Evaluation, 740, Mississippi River, Blvd S. #15E, Saint Paul, MN 55116, USA

Received: October 15, 2025 | Published: November 4, 2025

Citation: Shroff FMC, Patton MQ. Seeing the Elephant in the room: structural power dynamics and research relationships. Sociol Int J. 2025;9(5):181-186. DOI: 10.15406/sij.2025.09.00436

Using a duo ethnographic methodological frame, this article chronicles a professional relationship that transpired years ago, one that created a negative impact on one person and was inconsequential for the other. Happenstance brought the pair together with the passage of time, and they were able to address the power dynamics that had occurred in that first encounter years ago. Now, as both professionals had evolved in their understanding of human relationships and anti-racism, feminism and decoloniality, they discuss these issues within the context of their subject positions–one as a man of European heritage, the other, a woman of South Asian/Middle Eastern heritage. In their first encounter, the power difference between them was significant. The dialog in this article is honest, vulnerable and unusual. It is a shift from the standard professional conversation where productivity is seen as the most important and often only metric. Both Farah M Shroff (hereafter referred to as FMS) and Michael Quinn Patton (hereafter referred to as MQP) have now arrived at similar analyses of power in relationships and how this power emanates from socio-economic structures. They name the elephant in the room of their first encounter–sexism, racism, and other forms of oppression, coming up with a path forward for their own working relationships which they hope will illuminate a path for others. As a type of scholarly inquiry, duo ethnography provides a method that is interactive and collaborative, in which two researchers engage in a dialogue and share perspectives on their divergent experiences of a situation to identify and extract larger societal themes, then report what they’ve learned in a dialogic format. The scholarship builds on classic and foundational social science grounded in the sociological imagination, intersectionality, qualitative reflexivity and praxis, and the social construction of knowledge. Given the prevailing ideological climate, this conversation feels increasingly urgent.

This article exemplifies duo ethnography, an interactive and collaborative method in which two researchers engage in a dialogue and share perspectives on their divergent experiences of a situation to identify and extract larger societal themes.1 The interactive process manifests “the sociological imagination” as articulated by C. Wright Mills2 in which private, personal experiences can be understood and interpreted as illuminating larger and broader societal issues. In this case, the dialogic inquiry focuses on the intersectionality of power, privilege, race, and gender as illuminated in the writings of bell hooks,3,4 Kimberlee Crenshaw,5 Tania Das Gupta6,7 and Noga Gayle8,9 Examining intersectionality through duo ethnography supports the social construction of both meaning and knowledge.10 Duoethnography involves interrogating and reconceptualizing these beliefs and experiences through conversation that is reported in a dialogue format. As a fundamentally qualitative research method, duo ethnography is grounded in reflexivity (being aware of how one’s background and societal status affect perception and experience) and praxis (the political stance of the researchers), which together position the inquiry personally, professionally, and scholastically.11 The inquiry begins retrospectively, moves into the present, and offers a perspective on implications for the future.

Exposing power dynamics with broader societal implications

FMS’ supervisors for the summer job had hired MQP. With the tacit approval of MQP, the supervisors carried on with their project unchanged, and continued their treatment of FMS. They denied her access to various benefits so the job became more difficult; all of this was linked to the visit by MQP.

The experience was stressful and challenging for FMS, while MQP was oblivious to the effects and consequences of the interaction. Years later, an opportunity emerged for a dialogue about the incident when a mutual colleague opened the door for engagement.

All meetings for this article were attended by FMS and four of her research assistants, all of whom were of South Asian heritage (three of whom identify as women) and thus felt more compelled by the subject matter. Because of the intergenerational nature of the learning that occurred in the process of conceptualizing and writing this article, the research assistants have offered their reflections about this process and how it gave them confidence to proceed in their professional lives. This modelling of frank conversation about racism, sexism, and colonialism helped the research assistants to call out these dynamics in their own lives.

This article delves into this dialogue between FMS and MQP – its revelations, insights, and implications. We begin the dialogue by introducing ourselves to readers and, not incidentally, to each other.

FMS: As a Kenyan born Canadian Parsi, I have lived most of my life on the lands of the Coast Salish nations on the West Coast of Turtle Island, a.k.a. North America. I love being a Parsi and am grateful to my parents, grannies and auntie for raising me; I am very involved in my community, including leading an oral history study of those who identify as women: zxx.med.ubc.ca

I founded a global public health organization that aims to uplift of young ones, the environment, and those who identify as women. I am also a consultant and faculty member at the University of British Columbia. Much of my focus is on solving health problems using evidence based solutions that are either free or low cost. Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health awarded me a mid-career fellowship in 2021-22 and i continue to collaborate with colleagues at Harvard.

As an activist scholar, my life and work are mirror reflections. Feminism, anti-racism and decolonizing ways of being are integrated into my everyday life and work. Equally, yoga, meditation and other spiritual practices are key to my wellbeing and I love teaching them to others. I’ve taught yoga in over 60 countries, and never cease to be in awe of how much inner peace it generates for our stressed world Namaste.

MQP: I am of Scot-Irish genealogy but do not know the details of when and why my ancestors migrated from Europe to the United States. My father was a factory worker and I grew up in a racially mixed lower income neighborhood. I graduated from college at the height of the Vietnam War and rather than risk being drafted into the military, I went into the Peace Corps in Burkina Faso (then called Upper Volta) in West Africa. I worked with subsistence farmers, the Gourma people, doing agricultural development. Gourma means “human being” in the Gormanche language. I was called bompieno meaning “white thing.” Following the Peace Corps I completed graduate school and became a professor at the University of Minnesota in sociology.

FMS: I don’t know if you do remember me at all, but I remember you very well.

We met many years ago when I was doing a summer research project as a student; we were doing interviews asking about what health means and what communities can do to improve their health. The communities we were interviewing were composed of Indigenous peoples and non-Indigenous peoples who were immersed in holistic health practices, as well as others.

At the time, I was just coming into my scholarship and scholarly activism as a feminist and anti-racism health researcher. The supervisors who were running the project didn’t agree with the approach that I was learning to take. They specifically were not in agreement with the anti-racism approach and one of its corollaries, which was the support for traditional Indigenous worldviews related to wellness and other systems of natural medicine, which were very big in the community at that time. I was sympathetic to the majority of the people who we were interviewing and i recognized that objectivity was not possible. None of this meant that I had difficulty in being a neutral interviewer. My interviews were neutral conversations. As a budding researcher, I was finding my feet and they pushed back in a way that was stressful for me.

As that process was unfolding, you were brought in to do a qualitative methods workshop, convened and sponsored by those supervisors. During the workshop, I raised some questions about interviewing and the larger perspective that we could be taking, to contextualize the interviews. My memory, and please correct me if this is not your memory-- is that you agreed with the criticisms of those two gentlemen.

I felt like I had hit a sort of wall. You were the expert who had just been brought in; once you chimed in and agreed with them, it essentially gave them more support. The way that I heard it was that feminism and anti-racism perspectives weren’t legitimate. The direction of the interviews was changed after your workshop. You were a big voice. After you left, I felt like there was really no hope that the interviews would be carried out in a fashion that genuinely allowed for participants’ voices to be heard in an authentic fashion, so the project changed significantly. That’s my memory of our encounter.

MQP: It's been many years, and I confess I do not remember our interaction at the workshop. Based on your recollection and experience, I judge my behavior to have been professionally inappropriate and ethically irresponsible. I can imagine that, as a consultant sponsored by the very supervisors that were opposing your research approach, I acquiesced to their perspective. I was insensitive to the harm my comments made. More generally, I appear to have been inattentive to the power dynamics of such a situation.

I'm wondering if you can recall more about the specifics of our interaction. What do you remember asking and what do you remember of my response? The details may help us identify what a workshop presenter should be aware of when questions arise and what kind of response is appropriate given the constraints of a workshop setting. I appreciate your openness to examining what happened and I apologize for the pain and consequences of my actions. I appreciate the opportunity for us to examine and learn together how such interactions should be handled more appropriately and ethically.

FMS: You were teaching a workshop for staff, including us summer students. I asked you about how we can do objective research within the context–Indigenous communities and a non-Indigenous people who had a significant interest in natural medicine. I had been doing interviews with people in the area as part of the job. I asked you to talk about anti-racism interviewing. The men in charge of the project gave you a bit more information from their perspective, noting that they were trying to keep these interviews objective. Your answer was in agreement with them. You upheld their notions that interviews could be objective. The men who were in charge were concerned that biases would creep in if they entertained concepts such as anti-racism and decoloniality. You agreed with them. Unbeknownst to you, your voice tipped the scales. The men in charge now had an expert who agreed with them. It made my summer of work much more difficult.

MQP: It appears that I responded to your workshop question without engaging with you to understand the context for and implications of your question. For that, I apologize and am sorry for the subsequent difficulties my ineptitude caused.

But I can't imagine even then that I thought that there was such a thing as objective interviewing. I've been writing about subjectivity since my very first writings. But I did and continue to write about neutral interviewing, which is about being non-judgmental as an interviewer. That’s different from objectivity, which ignores the inevitable effects of culture and context.

But it is possible to interview in a way that is non-judgmental, what I've called “empathic neutrality.” Empathic neutrality is communicating that a person's story and perspective is hugely important, but that there's nothing they can say that is right or wrong, or will shock me or offend me or please me. So, that's neutrality. I can well imagine that I thought that framing your research as “anti-racism” biased responses. I can imagine advising that the research be framed as inquiry into the experience of health in the Indigenous context. But I can well imagine that I took the position about neutrality that they would have interpreted as they did. To have framed something at that time as anti-racism research would have been perceived as being biased within the academy.

I don’t think that my critique at the time would have been about the methods you were using or the subject matter you were exploring. In fact, the examples you give of what you were asking constitute good, open-ended qualitative interview methods. But to label something as anti-racism is to already prejudice the conclusion of the study – I imagine the supervisors found that to be problematic as, apparently, did I. What your experience and response opens up is how labeling and framing affect judgments. Terms like objectivity and neutrality evoke strong reactions, as do terms like anti-racism and social justice. So that's what comes up for me.

FMS: The two of us agree with the research methodological concepts as you have outlined them. The other thing that came up for me, Michael, was that not only was I talking about anti-racism scholarship, but I was a brown woman. The two supervisors were white men. And they thought they were objective and unbiased.

And as the workshop presenter and supposed expert, you were also a white man. I was a student. All the power dynamics were present, but not acknowledged.

MQP: Yes, at the time I would not have thought consciously about the power dynamics of my being a white male professor interacting publicly with a brown female student. My arrogance, I’m sure, was palpable to you – while I was clueless, even oblivious.

With that in mind, let me ask you now to provide more context for your situation at that time and what brought you to the workshop I was doing. The context for me was that I had just published the second edition of Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods and was promoting the book through workshops. The qualitative vs quantitative debate was still raging at that time. I was working to legitimize qualitative methods in evaluation.

FMS: My context was that of an inquiring young mind who was constantly asking how we could make the world a better place. I cared about making people healthier, and I cared about addressing power dynamics which created the conditions for some people to be much healthier than others. Racism was one of those power dynamics, as was sexism.

In most professional relationships, hierarchies are not discussed. They are invisible and ignored, like the proverbial and invisible elephant in the room. That failure to acknowledge power dynamics and hierarchies has profound impacts on virtually every aspect of professional communication and decision making.

Without falling into the trap of a victim/oppressor dynamic, let’s explicitly unpack the nuances of the terrain that exists between two people who come from vastly different places in the social landscape – as was certainly the case in that workshop years ago.

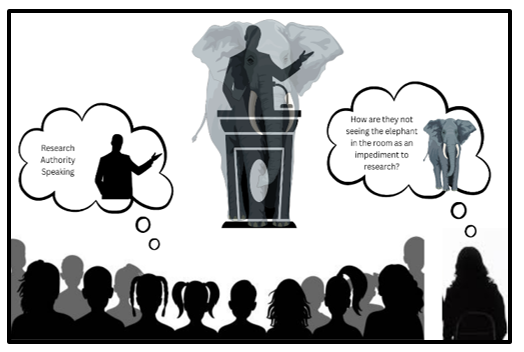

MQP: Let me pick up on the saying that “there is an elephant in the room.” We understand that this means an obvious problem, like racism, is being ignored, or people are pretending that the problem doesn’t exist so it goes unacknowledged and undiscussed. The “elephant” in this case was the power inequalities and racism embedded in the workshop I was conducting. You were keenly aware of the elephant but I and others were not. Looking back, based on our discussion, I can now see the elephant, though we may not see precisely the same elephant. Indeed, we’ve been grappling with how to describe the racism and power inequities at play in the workshop (Figure 1).

Figure 1 The elephant in the room and not knowing it (MQP) and seeing the elephant in the room (FMS).

By Divya Dhingra (with help from Ashkan, earlier versions)

FMS: As a woman in a brown body, I was beginning to articulate the ways in which others may be dismissive of me and my ideas, purely on the basis of who I was and the ways in which people perceived of me, based on their own assumptions. I found this analysis of power relations to be tremendously liberating. As feminism had taught me not to blame myself for sexist interactions, this more complex intersectional perspective explained the double impact of my status as a person of color.

Back in those days as a student, I was starting to see that if people from dominant subject positions made the same comments as me, they were taken up in different ways. So I could see you, Michael, as a powerful man of European heritage, whose words buoyed the words of the two bosses, also of European heritage. The elephant in the room was sexism, or even misogyny, plus racism, neo-colonialism and other forms of structural oppression which have impacts on professional relationships.

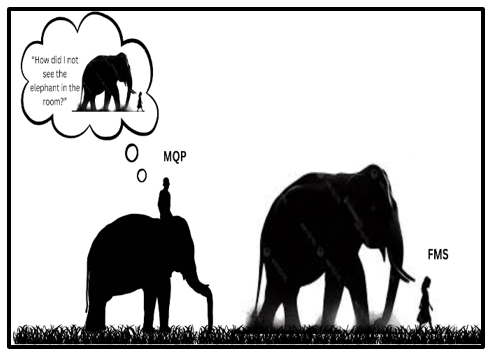

MQP: So now these many years later, as the illustration below shows, I wonder how I not saw the elephant in the room. As the illustration depicts, I am now aware of the elephant that was in the room. The answer is clearly that I was in the place of privilege and authority and oblivious to the effects of that oppressiveness by following you’re bringing me into that awareness.

I reflect on the questions I should have asked then. What brought you to your inquiry into anti-racism interviewing? What was your situation? What was the context for your study? The terminology of “antiracism” is fairly common now, but would have been unusual and new at that time. What was the political, organizational, and cultural context for your work? (Figure 2).

Figure 2 How did I not know? (MQP) and journeying together towards scholarly integrity and social justice (FMS).

By Divya Dhingra (with help from Ashkan, earlier versions)

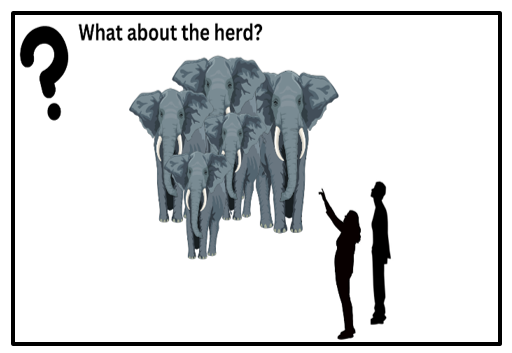

MQP: So let’s go deeper for here’s where the “elephant in the room” metaphor becomes inadequate. That elephant in the room is not there in isolation. Focusing on and examining a lone elephant is part of the problem. The parable of the 7 blind people (usually 7 blind men, actually) and the elephant suggests that if we combine the different parts of the elephant touched by the blind seekers, that is, connect the legs (like a tree trunk), side (like a wall), ears (like a fan), tail (like a rope), tusk (like a spear), and the elephant’s trunk (like a snake), we will see and understand the whole elephant. But to understand the elephant, we need to understand it as a member of a herd. This means seeing the elephant as part of an ecological system in relation to other flora and fauna where the elephant evolved in Africa and Asia. For the purpose of our discussion, then, the elephant in the workshop was a member of a larger herd constituting societal racism and power inequality. It’s not adequate to deal with racism and inequality in the workshop by itself without placing it in the larger systems context of societal systemic and structural racism and power inequities. The workshop is a window into that larger, more all-encompassing system. Dealing with societal, structural racism and inequality is where this discussion takes us – not just doing better with a workshop process.

FMS: Meeting you after all these years is powerful. Not only have critical changes within North American society occurred, but my life and your life have changed as well. How can we now conceptualize a framework using critical reflection and an equity lens, which would help to frame an encounter between the two of us, and by extension, people who are like the two of us – with the aim of clear communication which allows for social justice to be central?

Such models exist: The Coin Model of Privilege and Critical Allyship,12 The EThIC model of virtue-based allyship development,13 Triple A Model of Social Justice Mentoring.14

Perhaps in our context, a blend of some of these models makes the most sense. Ideally, we hope to sketch a potential way forward for professional relationships to honestly engage in structural power relations in a way that allows each person's talents to shine.

MQP: That’s powerful framing: “to honestly engage in structural power relations in a way that allows each person's talents to shine.” That certainly didn’t happen in our interaction at that workshop. Now, these many years later, I’m having the privilege and learning experience to be working with Indigenous colleagues on ways of engaging together authentically – and this dialogue with you.

FMS: Models can help illuminate, but our conversation reaffirms the centrality of relationships; it also acknowledges and deals openly with racism and power dynamics. I hope that students and young professionals reading this have the foresight and courage to assert their perspectives and take on hard questions. What do you take away from this?

MQP: A lesson for me is the importance of asking questions about questions. North American culture is heavily answer-focused and answer-biased. This means we don’t spend the time to get the question right. Before answering your inquiry about methods, I should have asked more about what you were doing and why. Instead, I answered without sufficient context.

That’s what I should have done in the workshop. Rather than answer your question, I should have asked more questions to establish the context for and consequences of your question (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Seeing the herd and joining it: converging questions about power dynamics and research relationships. By Divya Dhingra (with help from Ashkan, earlier versions)

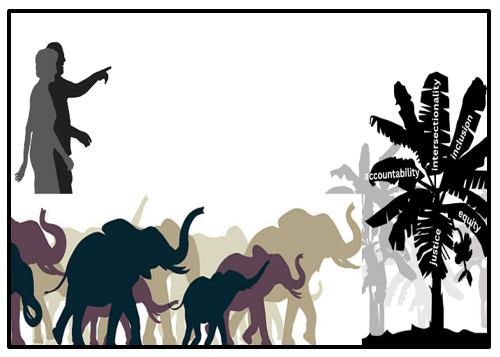

FMS: It’s been a positive aspect of my professional and personal life to meet you again, Michael. We have grown in similar directions, and now we are asking similar questions. We both wish to inquire about the elephant herd, out of the room and now in their natural ecosystem. What do we have to learn from the herd?

FMS: Elephant herds are led by a Matriarch, a wise and caring leader. The herd is a close-knit unit that supports and protects each member. They take risks for each other. Our newfound relationship is more important now, as an antidote in these times of polarization. We can learn from the elephant herd to be united, caring and led by wisdom. We can protect each other and develop trust. We can refuse to be divided by hate (Figure 4)

Figure 4 Being guided by elephants in an ecosystem of mutuality.

By Divya Dhingra (with help from Ashkan Saffari, earlier versions)

I leave you with the words of a Persian poet, Sa’adi (from Golestan (The Rose Garden), Chapter 3, Story 28):

The Elephant and Hair

Use kindness when thou seest contention.

A sharp sword cannot cut soft silk.

By a sweet tongue, grace, and kindliness,

Thou wilt be able to lead an elephant by a hair.

Reflections by FMS’ research assistants

As Research Assistants working with Dr. Shroff, we found the dialogue between her and Dr. Michael Quinn Patton to be a meaningful example of how individual dynamics shaped by lived experience, identity, and power can dramatically influence how a professional interaction is felt and understood. What stood out to us was how the same moment was experienced so differently by each of them. As four students from South Asian backgrounds beginning our journeys in the research world, we are all hyper aware of the systemic racism and discrimination put onto us which unfortunately conditions us to view interactions in a different way than our white counterparts. Moments that may seem small or insignificant to others can often carry deeper weight for us, because they echo larger patterns of what we've seen or felt before.

The extended metaphor of the elephant herd utilized throughout this piece to illustrate the structural dynamics at play began from our meetings, where we research assistants and Dr. Shroff formulated this maternal herd, led by her, with a shared purpose of expressing her perspective on the interaction and helping to unpack the complex dynamics of power in research. We also got to share our personal thoughts and experiences on the topics discussed above in the manuscript. What follows next are those reflections put into words, sharing our personal experiences on what it meant to be a part of this collective experience.

As a woman of colour starting her journey in research, the intersectionality of my identity makes me a more thoughtful and attuned researcher, though it can also make me hyper aware of my position and the dynamics at play in the spaces and conversations I engage in. I’ve had several moments where an interaction that I have had or an interaction I have witnessed a peer having has made me too aware of the power dynamics at play while the other person had the privilege to be unaware. I find that in those situations it is often myself or my peers doing the intellectual labor of reading the room and readjusting our approach while the other person is unaware. Therefore, getting to participate in such a piece alongside Dr. Shroff and Dr. Patton has been so empowering to me. For once, the emotional and intellectual labor is shared. We’re naming the power dynamics, talking about them openly, and making space for everyone’s voices to be heard, including those of us who are still early in our careers.

Assisting on this piece has made me reflect deeply on if I am doing enough to prompt these conversations. It’s often easier to stay quiet in uncomfortable situations but it is equally as important to speak up so that we can change these things because sometimes it is not malice that is causing this but ignorance. If we bring attention and awareness to these interactions, we can work together to try to rebuild those relationships like Dr. Shroff and Dr. Patton have done through this manuscript. This experience has taught me that even as someone who has to be aware of the dynamics at play in the spaces I engage in, I also have a lot of privilege in other ways. I have the privilege of a strong community, with my peers and fellow women in science as well as leaders like Dr. Shroff and I can take that community and open its doors to others as well who need such spaces. To me, I feel that is a tangible step that I can take towards making research more open, honest, and equitable.

There were moments in those conversations where I found myself just sitting and taking it all in - not because I didn’t have anything to say, but because I was genuinely learning. Watching how they unpacked their interaction, how Dr. Shroff and Dr. Patton navigated tension with curiosity rather than defensiveness, was something I won’t forget. It made me think deeply about how power and positioning show up, even when we don’t mean for them to. As research assistants, we were invited into the dialogue more than once - not just as observers, but as participants. That mattered. It reminded me that our perspectives hold weight, even if we’re still early in our journeys. Dr. Shroff had a way of making us feel like we were part of the process, not just helping it along.

Being involved in the literature review was another layer of learning. So much of what I read pointed to the need for research to name the structures its part of - especially when those structures exclude or marginalize. It’s not enough to be thoughtful; we have to be willing to be uncomfortable, to challenge what feels familiar. This project showed me what that can look like in practice. I’m proud to have contributed in whatever small way I could.

During the initial stages of this manuscript, Dr. Shroff had gathered all the research assistants together to not only tell us about our duties during the creation of this dialogue piece, but to also tell us her side of the story. At the time, as a young South Asian woman and someone who feels deeply about the various injustices of the world, I found the experiences detailed by Dr. Shroff to be outrageous! Even before entering the meeting with Dr. Patton, I held preconceptions about who he could be. However, after our first meeting, I found myself surprised - not just about his side of the story, but also his sincerity and passion. So much so that I mistakenly blurted: "Wow! You are quite different from what I had thought", essentially implying that I had previously thought of him as some sort of evil antagonist. Although that revelation had been humorous at the time, looking back on the almost 9 months I've spent as a research assistant, not only did I learn the essential skills of research (literature review, editing and revising, etc.), but I also learned more about the research world. Much like real-life, the world of academia is not as black and white as I had assumed. The interactions and conversations that one finds to be wholly neutral, could be a negative experience for another. Through this project, I learned the importance of context, tone and intention in an interaction, and how even the presence of an implicit power dynamic can play a significant role. By observing the efforts made by Dr. Shroff and Dr. Patton to rebuild their relationship as peers, I began to appreciate the significance of empathy, communication and perspective. As I move forward in my research journey, my experience as a research assistant in this project will remain a focal point - a reminder of my own privilege and my inspiration towards making research more accessible, open and diverse.

As a South Asian woman and second-generation immigrant at the beginning of my research career, I have had experiences where I have sought out information on how to navigate the world of research and have been invalidated by a professional in my pursuit of understanding and building my potential research career. Seeing Dr. Shroff’s experience has allowed me not to feel alone or at fault for how my experiences with other research professionals have been. It was not a personal failing on my part but rather a power dynamic inherent within the research arena.

This realization, the importance of recognizing power dynamics, is enlightening and crucial for all of us in the research field. In contrast, working with both Dr. Shroff and Dr. Quinn Patton allowed me to gain the confidence to share my ideas and insights and to dispel some of the doubts instilled in me by previous researchers. Witnessing the process of sharing ideas freely and building upon them to gain clarity, rather than trying to be right or perfect, from seasoned research professionals, was empowering. Supporting this research experience deepened my understanding of how to move beyond theory and apply these insights in my everyday life. Part of this means being mindful of whose voices are missing from the conversation, recognizing moments when I may be silenced, and using those observations as a catalyst to resist harmful dynamics. It also means finding strength and courage in the face of systems that often seek to limit or exclude. The strength, humility, and compassionate, and active questioning I witnessed during their dialogue are qualities I will carry with me throughout my professional journey.

we would like to thank our friend/colleague Jessie Sutherland for encouraging us to talk with each other. I (FMS) would like to thank my wonderful research assistants, Divya Dhingra, Ashkan Saffari, Satvika Suresha, and Mandeep Bhabba for their support, mirroring, and depth of understanding during this vulnerable and rather difficult process for me. I also really appreciate their skill in doing the drawings.

There is no conflicts of interest.

©2025 Shroff, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.