eISSN: 2576-4470

Review Article Volume 2 Issue 6

1Department of Sociology, Niger Delta University, Nigeria

2Department of Community Medicine, Niger Delta University, Nigeria

Correspondence: Raimi Morufu Olalekan, Department of Community Medicine, Environmental Health Unit, Faculty of Clinical Sciences, Niger Delta University, Wilberforce Island, Bayelsa State, Nigeria

Received: November 04, 2018 | Published: November 29, 2018

Citation: Abdulraheem AFO, Olalekan RM, Abasiekong EM. Mother and father adolescent relationships and substance use in the Niger delta: a case study of twenty-five (25) communities in Yenagoa local government of Bayelsa state, Nigeria. Sociol Int J. 2018;2(6):541-548. DOI: 10.15406/sij.2018.02.00097

Background: In the Study, Mother and Father Adolescent Relationships and Substance Use in the Niger Delta: A Case Study of Twenty-Five (25) Communities in Yenagoa Local Government of Bayelsa State, Nigeria. The extent of social interaction between parents and adolescents in Yenagoa Local Government was determine, the association between the level of interaction between the father and child on adolescent’s predisposition to substance use in Yenagoa Local Government Area was determine and the association between the level of interaction between the mother and child on adolescent’s predisposition to substance use in Yenagoa Local Government was examine.

Materials and method: Data obtained were analysed using both descriptive analysis and inferential statistics. Data was analysed descriptively using frequency and percentage while result was presented in table. Data was also presented pictorially using charts.

Results: Results showed that 27.3% of respondent had very cordial relationship with their fathers while 34.5% had very cordial social interactions with their mothers. This indicate that majority of the respondents do not have cordial relationship with their fathers and mothers. Further analysis revealed that 60.0% and 94.4% of the respondents do not have cordial relationship with their fathers and so are predispose to substance use. Also, 86.0% and 86.2% of the respondent do not have cordial relationship with their mothers. Indicating that majority of the adolescence were predispose to substance use.

Conclusion: The study concludes that, it is vital for parent and societies to seize the opportunity of applying behavior modification therapy to juveniles and young adults. as the need arises. It is also imperative that all stakeholders engage in concerted efforts to target both parents and adolescents in substance use control strategies.

Keywords: mother, father, quality, adolescent, substance use, interactions, Niger delta

Parenting is a ministry and it’s the most important profession in the world. Parents are the first coaches a child has and communication between parent and adolescent will help in guiding some of the decisions an adolescent will make. Positive communication within the family structure is significant and may prevent substance use among adolescents.1–3 Parents can have a positive or negative influence in the decisions the adolescent will make, therefore, the relationship between a parent and adolescent can influence substance use by some adolescents. It has been suggested that when an adolescent and parent have a strong interpersonal relationship the adolescent will try to maintain parental approval by making positive decisions in life.2 When there is a positive family environment, oppositional behaviors decrease, positive communication skills are formed, and there is a positive relationship between the parent and adolescent.2 It could be suggested that when there is a positive, rewarding relationship between a parent and adolescent it could help in preventing the adolescent from substance use.

Strong communication patterns between parents and adolescents can help in preventing delinquent acts of adolescents.2 one must consider all determinates when looking at this factor, such as the adolescent’s age and sex and the parent’s marital and social statuses. Interpersonal relationships are built solely on the communication patterns that exist between the parent and adolescent.2,4,5 Some families rely on their patterns of communication to help in building anticipated forms of behavior within the family.2,5 An important factor is whether the parent allows for open forms of communication. With an open form of communication, adolescents will be open in the ways they express issues with their parents. For example, in allowing open communication parents and adolescents would be able to interchange ideas about substance use and talk about the hazards of using a substance.6 Riesch7 notes that open parent-adolescent communication can help in the discussion of components that can prompt involvement in health-risk behaviors. The communication between the parent and adolescent focus is what helps in decreasing delinquency.2,7 Based on the communication patterns that are practiced by the family will either help in decreasing or increasing delinquent behaviors such as substance use.2,6 When the form of communication is open, there is a decrease in delinquent acts; whereas, if problem communication is utilized more between the parent and adolescent there is an increase in delinquent acts, making the adolescent more susceptible to substance use.6 It has been found that adolescents abstain from substance use when they learn about the risks at home.6 If there is an open form of communication with either parent, the adolescent will less likely be associated with delinquency, but, on the other hand, if there is a problem with communication between either parent and adolescent there is a great chance that the adolescent will be associated with delinquency.6,7 Parents can help in influencing their adolescents in not participating in substance by open communication about the problem at home.6 When a parent makes it known that they do not approve of substance use, the adolescents may be less likely to use a substance.6 It is notes that when a parent is anti-smoking it can play an important factor in preventing the adolescent from smoking by the types of socializing practices the parent utilizes with their adolescents, such as the parent’s attitudes towards an issue, educating the adolescent on issues, and setting rules. When the parent and adolescent interact together, in close interpersonal ways, the adolescents will be less likely to participate in substance use.8,9 suggests that verbal communication is the key ingredient in a parent expressing their concerns about substance use which in turn may prevent the adolescent from engaging in substance use. Consistently talking with their adolescent and providing good consistent dialogue to the conversation can help in educating the adolescent about the perceptions the parents have on the issues. When parents discuss substance use issues with their adolescents it has to be multidimensional and the adolescent must understand the content in order for it to be effective.6 If the parent and adolescent have either on-going talks about substance use throughout the child’s adolescence it shows that the talk about substance use may be important in the adolescent’s understanding about substance use risks.2,6 Kelly, Comello & Hunn10 found that when the parent is actively involved in open dialogue that express behavioral norms, there will be a decrease in the adolescents’ views of the norms as externally imposed; thus, increasing the chances that adolescents will behave in accordance with the norms held by their parents.10 Consequently, some parents may feel that they cannot influence their adolescent from substance use, and in a survey conducted by the Partnership for a Substance-Free America in 2002 56% of parents surveyed noted that they wanted to be able to better communicate with their adolescents about substance use.6 The relationship between the parent and adolescent has to be viewed as positive one in order for it to be an effective one. When important issues arise, who adolescents will seek information from is an important factor. Adolescents will have the options of obtaining advice from friends, siblings, or other family members with some never considering going to their parents for information. This can be swayed by the way the parent approaches the adolescents about hard to talk about issues.2,6 Kelly10 found that when an adolescent is approached by at least three people to discuss the dangers of substance use, there will be a low substance usage reported. Parental sanction may be amongst the reason adolescents choose not to use a substance.6 when the parents offer more praise and encouragement, set rules, and conveys trust, the adolescents will be less likely to engage in substance use. Adolescents will not want to break the trust bond that exist between them and their parents and seek to have their parent’s constant approval. When the parent does not offer any emotional connection, set rules, or encouragement and praise, adolescents may turn to a substance as a cry out for some attention from their parents. The youth will respond in ways to try to obtain attention from their parent that adolescent may feel they lack. When adolescents do not find that open form of communication with their parent and cannot express themselves openly, they may engage in delinquent acts; thus, when they are not able to express themselves openly with their parents it may result in low academic achievement and associating with substance-using friends.7

Substance abuse is an important national, social and health problem in almost all countries in the world including Nigeria. Data from around the world suggests that substance use often starts between the ages of 14 and 15.11,12 There are numerous reasons given for this fact. However, the predominant reason seems to be that adolescence is a period of transition, in which individuals seem to be more impulsive, reckless and non-conforming than during other developmental stages of their lives.13 Many adolescents engage in substance use activities, which they do perceive as risky, but are somehow acceptable within their peer groups. As a result, risk behaviours (including substance abuse) during the adolescent years are of major concern in Nigeria today. In Africa, the Nigerian experience is quite alarming. According to the National Drug Law Enforcement Agency (NDLEA),14 the use and abuse of drugs by adolescents have become one of the most disturbing health-related phenomena in Nigeria and other parts of the world. In Nigeria, most people use such drugs as coffee, colanut, and cigarettes for staying awake; or take alcohol and tobacco as a way of relaxation; or take painkillers like aspirin in reducing body pains. These are seen as licit drugs. However, the use or abuse of drugs such as cannabis or marijuana, cocaine, heroin and meth are seen as illicit in Nigeria. The widespread availability of these illicit drugs and frequency in its usage engenders its abuse.

According to the NDLEA 2014 report, drug use and abuse has been on the increase in Nigeria, despite efforts by anti-drug agencies in combating the menace. Statistics of arrest by geopolitical zones in Nigeria shows that North West, South West and North Central took the lead, while the South-South came fourth and has over 38% of the females arrested for drug offences (see Table 1), even though Katsina, Kano and Bauchi States constitute the highest in terms of the statistics of arrest nationwide. In Nigeria, there has been an upsurge in the use and abuse of psychoactive substances. This upsurge has been characterized by an increase in the mental disorders, criminal acts and cult activities (as currently experience in yenagoa) in both the higher institutions of learning and also in secondary schools.15 The high rate of road traffic accidents, increased violence and criminal behaviour are also partly attributed to alcohol and drug abuse.16 Also, there is scanty data on patterns of drug abuse in specific groups in the community. Due to increasing urbanisation of the country there is a tendency of changing patterns in illicit drug use therefore the need to constantly update information on the use of drugs among Nigerian adolescents. Linked to the above is a sharp increase in the cases of drug trafficking and abuse in the country and the most affected group has been identified as the youths between the ages of 16 and 45 years (Table 1).17

Geopolitical Zones |

Males |

Females |

Total |

% |

North West |

2,214 |

47 |

2,261 |

25.62 |

South West |

1,604 |

78 |

1,682 |

19.06 |

North Central |

1,344 |

72 |

1,416 |

16.04 |

South |

1,126 |

188 |

1,314 |

14.89 |

South East |

1,041 |

95 |

1,136 |

12.87 |

North East |

1,003 |

14 |

1,017 |

11.52 |

Total |

8,332 |

494 |

8,826 |

100 |

Table 1 Arrest by geopolitical zones in Nigeria

Source: Adapted from NDLEA 2014 Annual report.14

Note: North West, South West and North Central took the lead, but over 38% of the females arrested came from the South-South.

Large-scale epidemiological studies have shown that about two thirds of late adolescents have admitted to using tobacco, over 80% have reported using alcohol, and half have admitted to experimenting with marijuana.18 Overall, most adolescents admitted experimenting with an illicit substance rather than admitting substance-specific preference.18 Zapert & Snow19 noted that adolescent experimentation with alcohol, marijuana, cigarettes, and other illicit substances increased through 18 years of age and then decreased as individuals got older. Illicit substance use by adolescents between 16 to 18 years of age has been commonly associated with other unhealthy and unproductive behavior.20 illicit substance use affects many regardless of race, religion, culture, or socio-economic status.20

This study focuses on the Mother and Father Adolescent Relationships and Substance Use in the Niger Delta: A Case Study of Twenty-Five (25) Communities in Yenagoa Local Government of Bayelsa State, Nigeria.

To achieve this aim, the following specific objectives are to:

Description of the Study Area

Yenagoa became a state Capital when Bayelsa state was created in 1996, Yenagoa is geographically located between latitude 4° 47‟ 15‟ and 5°11‟ 55” Nothings and Long. 6°07‟35” and 6°24‟00” Eastings (Figure 1). The LGA has an area of 706 km² and a population of 353,344 comprising of 187,791 male and 165,553 females with an annual exponential growth rate of 2.9 as at the 2006 National Census.21 Yenagoa Local Government Area (LGA)22 is bounded by Mbiama communities of Rivers State on the north and East, Kolokuma/Opokuma LGA on the north west, Ogbia LGA on the south and Sourthern Ijaw on the west, Ogbia LGA on the South East and Sourthern Ijaw on the South west.23,24

Yenagoa Local Government Area is located on the banks of Ekole Creek the latter being one of the major river courses making up the Niger Delta‟s river,25 with only one political/administrative ward namely: Epie-Atisa.24 There are 21 communities within the study area namely; Igbogene, Yenegwe, Akenfa, Edepie, Agudama, Akenpai, Etegwe, Okutukutu, Opolo, Biogbolo, Yenizue-Gene, Kpansia, Yenizue-Epie, Okaka, Azikoro, Ekeki, Amarata, Onopa, Ovom, Swali, Yenagoa.

Yenagoa Local Government Area is the traditional home of the Ijaw people, Nigeria's fourth largest ethnic group after the Hausa, Yoruba and Igbo. The Ijaws form the majority of the town. English is the official language, but Epie/Atissa language, one of the Ijaw languages, is the major local language spoken in Yenagoa. Other Ijaw dialects include Tamu, Mein, Jobu, Oyariri, and Tarakiri. There are other pockets of ethnic groups such as Urhobo and Isoko. There are local dialects in some places. Other notable languages in the LGA are Epie, Atisa, Nembe and Ogbia. Christianity and traditional religion are the two main religions in the State. The culture of the people is expressed in their unique dresses, festivals, dietary habits, arts and crafts, folklore and dancing. These distinguish the people from other ethnic groups. The major crafts include canoe building, fish net and fish traps making, pottery, basket and mat making (Figure1).

The study designs adopted for this research work were quantitative analysis and descriptive research method. Aggregate data were analyzed for the purpose of this research. Structured questionnaire and Oral interview were used for collection of primary data.

Population of the study

The population of the study 352,285 residents of Yenagoa Local Government comprising of 182,240 males and 170,045 females26 and the population was projected to 2017 using annual exponential growth rate of 2.9% as population growth rate as at the 2006 National Census.21 This gives projected population of 482462 people.

Sample size

A sample size of 400 was estimated using Taro Yamane formula as presented below (Table 2):

Where, = population size = 482462, e = level of significance = 0.05.

Hence, the sample size was approximated to 400.

Four hundred was settled for, as the sample size for the study. The sample size is considered adequate for the study. The sample size was distributed evenly among the proposed rural communities in Yenagoa Local Government Areas as shown below:

Rural community |

Sample size |

Igbogene |

16 |

Yenegwe |

16 |

Agudama |

16 |

Akenpai-Epie |

16 |

Edepie-Epie |

16 |

Azikoro |

16 |

Akenpa |

16 |

Etegwe |

16 |

Okutukutu |

16 |

Opolo |

16 |

Biogbolo |

16 |

Yeneizue Gbene |

16 |

Yenagoa |

16 |

Kpansia |

16 |

Yenizue Epie |

16 |

Okaka |

16 |

Amarata |

16 |

Onopa |

16 |

Ovom |

16 |

Swali |

16 |

Koroama |

16 |

Tombia |

16 |

Sampou |

16 |

Kalaba |

16 |

Polaku |

16 |

Total |

400 |

Table 2 sample distribution of rural communities

Source: Researcher’s computation (2018).

Sampling methods

To enhance the reliability of the research work and achieve the desired goal, purposive sampling technique was applied in selecting the rural community each from the Yenagoa Local Government Areas respectively. Simple random sampling techniques were used in selecting the respondents. Respondents were randomly selected based on personal interview method with the aid of drafted questionnaires. Twenty-five (25) communities were visited in Yenagoa Local Government of Bayelsa State. These are stated above.

Instrument for data collection

The research instruments used for data collection were:

Questionnaire: This is a paper, which bears some questions that were answered by the selected respondent. The questionnaire contained questions framed to elicit relevant information from the respondents on social interaction between parents and adolescent’s predisposition to substance use.

Interview: This is a reliable method of collecting information where face-to-face verbal communication was employed.

Data obtained will be analysed using both descriptive analysis and inferential statistics. Data was analysed descriptively using frequency and percentage while hypotheses were tested at the 0.05 level of significance using chi- square. Result was presented in table and decision rule is to reject the null hypothesis if the chi-square calculated is greater than the chi-square critical or p-value less than 0.05. Data was also presented pictorially using charts.

Ethical consideration

During the course of this research work, the participants were accorded the due respect so as to ensure co-operation and information collected were treated with utmost confidentiality. The cultures of the community were also respected during the course of the research work. Informed consent was obtained from all of the participants.

Research question 1

What is the level of social interaction between parents and adolescents in Yenagoa Local Government? Result in Table 3 reveals that 27.3% of the respondents had very cordial relationship with their fathers while 26.0% and 46.8% had cordial and not cordial relationship with their fathers respectively. Result also shows that with their mothers, 34.5% had very cordial social interaction while 27.8% had cordial and 37.7% had not cordial social interaction with their mothers. This result indicates that majority of the respondents do not have cordial relationship with their fathers and mothers.

Questions |

No. of respondents |

Percentage (%) |

Social Interaction with father |

|

|

Very cordial |

105 |

27.3 |

Cordial |

100 |

26 |

Not cordial |

180 |

46.8 |

Total |

385 |

100 |

Social Interaction with Mother |

|

|

Very cordial |

133 |

34.5 |

Cordial |

107 |

27.8 |

Not cordial |

145 |

37.7 |

Total |

385 |

100 |

Table 3 Level of interaction with social interaction between parents and adolescents in Yenagoa local government area

Source: Field Survey (2018).

Research question 2

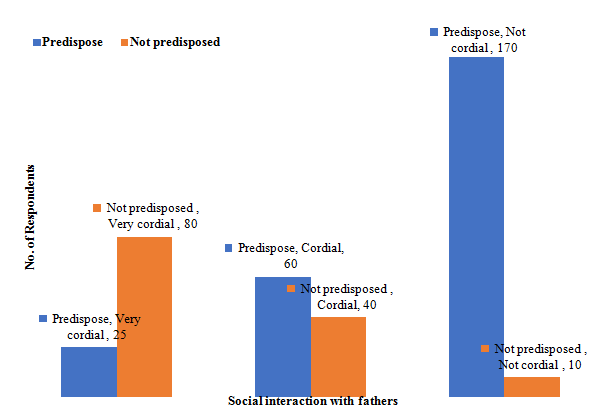

Is there any association between the level of interaction between the father and child on adolescents’ predisposition to substance use in Yenagoa Local Government Area? Result in Table 4 shows that 23.8% of the respondents who had very cordial relationship with their fathers were predispose to substance use while for those who had cordial and not cordial relationship with their fathers, the percentages were 60.0% and 94.4% respectively. This result shows that the highest percentage of those that were predispose to substance use were those that do not have cordial relationship with their fathers (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Level of interaction between the fathers and child on adolescents’ predisposition to substance use.

Predisposition to substance use |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Predispose |

Not predisposed |

Total |

How do you describe your interaction with your father? |

|

|

|

Very cordial |

25(23.8) |

80(76.2) |

105 |

Cordial |

60(60.01) |

40(40.0) |

100 |

Not cordial |

170(94.4) |

10(5.6) |

180 |

Total |

255 |

130 |

385 |

Table 4 Level of interaction between the father and child on adolescents’ predisposition to substance uses

Source: Field Survey, 2018.

Research Question 3

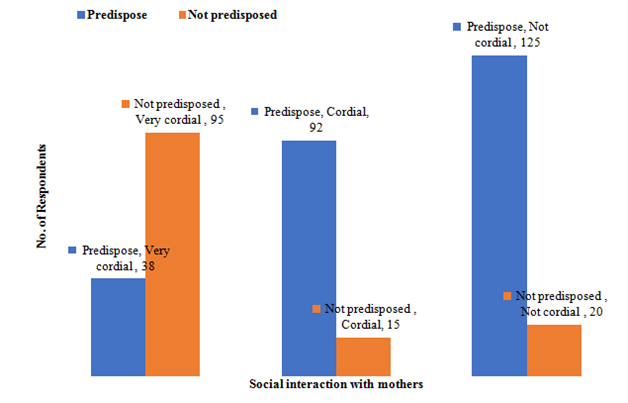

Is there any association between the level of interaction between the mother and child and adolescents’ predisposition to substance use in Yenagoa Local Government? Result in Table 5 shows that 28.6% of the respondents who had cordial relationship with their mothers were predispose to substance use while for those that had cordial and not cordial relationship with their mothers, the percentages were 86.0% and 86.2% respectively. This result implies that majority of the adolescence who were predispose to substance use were those that did not have cordial relationship with their mothers (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Level of interaction between the mothers and child on adolescents’ predisposition to substance use.

|

Predisposition to substance use |

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Predispose |

Not predisposed |

Total |

How do you describe your relationship with your mother? |

|

|

|

Very cordial |

38(28.6) |

95(91.4) |

133 |

Cordial |

92(86.0) |

15(14.0) |

107 |

Not cordial |

125(86.2) |

20(13.8) |

145 |

Total |

255 |

130 |

385 |

Table 5 Association between Level of Interaction with the Mothers and Adolescence Preposition to Substance Use

Level of social interaction between parents and adolescents in Yenagoa Local Government?

A parent is a model to his child and he is the main source for reinforcement, however, the family environment is the primary influence on children. Family socialization has been described as the link between the individual (psychologic and biologic) and the larger culture (sociodemographic and structural factors). The young person learns social behavior, including drinking behavior, during the ongoing socialization process with parents, older siblings, and peers.27 According to the ecological systems theory, both the social environment (e.g, family) and the quality of the relationships within the social environment (e.g, parent-adolescent relationships), play a role in adolescents’ development.28 Moreover, no one would argue that child upbringing is an easy task, or that adolescence is a trouble-free period of development. Fortunately, the social context of a young person is important for his/her well-being. Family and peers are significant socialization factors which play an important role in this context. However, not only is the role of socialization factors determined by a particular cultural context, but also by the time in which an adolescent, his/her family, and other factors live and interact. Therefore, this study reveals that 27.3% of the respondents had very cordial relationship with their fathers while 34.5% had very cordial social interaction with their mothers while the findings of this research support the assumption that, in adolescence, parents still play an essential role in the development of their children. Despite the increasingly important role of peers, parents occupy a “special” place in the lives of adolescents.29‒33 The experience of the family as a “safe nest” contributes to psychosocial adjustment and is a protective factor in the prevention of internalized and externalized problems during adolescence.34 Our findings indicate that majority of the respondents do not have cordial relationship with their fathers and mothers. Moreover, adolescents expressed an overall high-quality relationship with their mothers than their fathers. It is evident that social interactions, which play a significant role in adolescent, if not satisfactory, represent a risk factor for the development of substance use. In this case, some of the risk factors may be the parent’s education, poverty, values and norms of the environment. In general, the reports of adolescents on family relations were more congruent with the reports of mothers than of fathers, highlighting the central role of the mother in interpersonal family relations.

Association between the level of interaction between the father and child on adolescents’ predisposition to substance use in Yenagoa local government area?

It is commonly assumed that the nature of parent-child interaction is influential in shaping the self-concept and broader personality of adolescents. The evidence presented here suggests further that fathers' cordiality is related to a high level of communication with adolescents. The findings consistently show that a poor father and child on adolescents’ relationship quality, defined as adolescents’ perception of little warmth, support, and closeness in the relationship with their fathers is associated with a higher likelihood of engaging in substance use at an early age. In other investigations, father-only families have also been found to increase the risk of drug use among youth to a greater degree than mother-only families or intact two-parent families,35‒36 a finding that was not replicated in the current sample. While our findings do not support the hypothesis that the absence of parents would be associated with drug use among predominantly adolescents, the findings should be interpreted in light of the small overall sample size and low number of single parent households in the current study.

The results of Research Question 4 and 5 showed that a majority of adolescents felt as though they had no one to talk to about a serious problem. The adolescent will have options of receiving information from many sources, and if the adolescent is approached by someone to discuss the issue of substance use it could lead to preventing the adolescent from using a substance.10 Those individuals who felt they could talk to someone about a serious problem indicated that they would choose to talk to their mother (91.4%) or father (76.2). Adolescents are more likely to abstain from substance use when they are taught about the dangers at home.6 By the parent openly discussing his or her disapproval of substance use, the adolescent becomes less likely to use a substance.6 From the results of this study, it has been shown that communication with parents helps in preventing adolescent substance use. Understanding their parents’ views on substance use helps in guiding adolescents’ decisions to use or not use a substance. This study also found that adolescents wanted to be able to communicate openly with their parents about serious issues, such as substance use. Majority of the adolescents felt as though they did not have anyone to communicate with, which could cause them to turn to other sources of information. If the parents would open the doors for communication, it could help in aiding the prevention of adolescent substance use and help in decreasing the number of adolescents who engage in substance use. With this open door of communication, parents can help in influencing their adolescent not to use a substance.6 Otten is suggesting that effective communication with adolescents (i.e., providing sound information on substance use) can help in educating the adolescent about the dangers of substance use and possible prevention of the initiation of the behavior.

Level of interaction between the mother and child and adolescents’ predisposition to substance use in Yenagoa local government?

In many societies, mothers are the primary caregivers of children, and the primary providers of education at early stages of life, for both boys and girls.37‒39Adolescents having a higher quality relationship with mothers were prospectively linked to a lower likelihood to initiate substance use. Importantly, it has also been argued that the negative outcomes associated with living in a mother-only household may stem from economic deprivation.32 This study shows that majority of the adolescence who were predispose to substance use were those that did not have cordial relationship with their mothers.40

In conclusion, early adolescent years are major transition periods in child’s development. Moreover, it is vital that parent and societies seize the opportunity of applying behavior modification therapy to juveniles and young adults as the need arises. Generally, youths in rural areas especially in remote villages are vulnerable to misinformation and wrong company.

Recommendations

The findings show how communication difficulties can cause enormous stress on their own, but more importantly can lead to a plethora of other undesirable consequences such as militance behaviours especially in the Niger Delta Region of Nigeria.

Based on the findings of this research, it is recommended that:

None.

The author declares that there are no conflicts of interest.

©2018 Abdulraheem, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.