eISSN: 2576-4470

Research Article Volume 1 Issue 3

Department of Sociology and Anthropology, Southeast Community College Education Square, USA

Correspondence: Danvas O Mabeya, Department of Sociology and Anthropology, Southeast Community College Education Square, Lincoln, Nebraska, USA

Received: June 29, 2017 | Published: October 13, 2017

Citation: Mabeya DO. Education a valued cultural capital in the us! advantages and challenges associated with arbitrarily assigned ages of the sudanese lost boys’ in acquiring an education after resettlement. Sociol Int J. 2017;1(3):104-111. DOI: 10.15406/sij.2017.01.00018

Education is the most important and valued American cultural activity, where as it is not in Southern Sudan (cattle are). In the contemporary world, education is not only a cultural capital but has become a ‘VITAL CAPITAL’. It has become a survival toolkit in the modern society. This study explores acquisition of education among forty South Sudanese Lost Boys living in the greater Kansas City using semi–structured interviews. The central research question investigated in this study is this: What are the advantages and challenges of acquiring an education associated with the arbitrarily assigned ages to each of the Lost Boys during their resettlement in 2000!

Research in this study identified advantages and challenges associated with the arbitrarily assigned ages to each of the Lost Boys during their resettlement in 2000. Though the younger Boys started off without being allowed to work and earning an income, there was a clear reverse trend in terms of acquisition of social/cultural capital of the young Boys (minors). The Boys that were resettled as legal adults seemed to struggle with balancing work, acquiring English language and getting an education: whereas, those who were placed under foster families and started off as dependents eventually had a better opportunity to acquire English language proficiency from foster families. They were also placed in school, where they socialized with American children and improved their English.

Keywords: education, social capital, cultural capital, english language, equalizer, productivity, creativity, innovation, technological advances, economic and human development

Education is and remains to be one of the most important tools of human development. It is highly valued in the United States and the western world at large (as a cultural capital), while it has been given low priority in regions such as southern Sudan. According to Sana, “Education is central to development; it empowers people and strengthens nations. It is a powerful “equalizer”, opening doors to all to lift themselves out of poverty”. In other words “it is critical to the world’s attainment of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs)”.1 In short, education has become “vital capital1” like an economic good that not easily obtainable or acquired . It is through education that individuals and society, as a whole, are able to acquire economic and social progress. There is no documented country that has achieved sustainable economic development without substantial investment in human capital.1 It improves the quality of lives and leads to wide social benefits to both individuals and society at large.

In other words, education raises people’s productivity, creativity/innovation, and promotes entrepreneurship and technological advances.1 This means, literacy levels are related to economic and human development. According to Almendarez,2 there is belief that expanding educational opportunities and access promotes economic growth. For instance in the United States, education is the key to good life, but while in Sudan, most of the Lost Boys in this study received little or no education because they were mostly sent out by their parents to look for grazing land for family cattle which are highly valued in the Sudanese culture.3 As stated above, investment in human capital through education has been recognized as a key ingredient of sustainable economic development. In his empirical investigation, Collier4 found that civil wars were concentrated in countries with little education. In particular, he found that countries with a higher percentage of its youth in schools greatly reduced its chances of conflict. Sudan is a great example of a country where civil war has raged for over three decades, since its independence in 1956. Sommers5 adds that it is war that makes the case for providing educational responses to the needs of children and youth, who are at risk of civil war more than any other circumstance as their education is a vital protection measure from child soldiering.

According to Brophy,6 “the education system in Southern Sudan has always been under resourced” (p. 2). Therefore, for the refugee South Sudanese Lost Boys in the US, education was the way into adulthood and a successful life in the United States.3 The Lost Boys did not have a chance to get an education in Sudan, mostly due to a hostile environment and lack of resources. Since education is highly valued in American society, the Lost Boys who have successfully climbed the educational ladder have gained a status similar to that of American citizens in economic social mobility (middle class and high paying jobs). In reality, some have managed to surpass many American citizens (see analysis page 21-22), who are not as highly educated and in a lower economic class. Most of the Lost Boys, who participated in this study, were enrolled in educational institutions, while others had graduated from a two-year program of study at community colleges.

1‘Vital capital’ is used in this study as a disjuncture from the social capital theory to mean the most important or essential ‘capital’ (survival tool kit) that an individual must have to survive in the modern and complex world. This does not necessarily refer to only economic capital.

This study narrows down on a prior dissertation study, on the refugee South Sudanese Lost Boys in the greater Kansas City Area, and investigates the following research question: What are the advantages and challenges associated with the arbitrarily assigned ages to each of the Lost Boys in acquiring an education since their resettlement in 2000?

Sudan has continuously sustained civil wars amongst its demographic/religious/racial groups for over four decades since its independence from Great Britain in 1956. The war of 1983 triggered the exodus of the young Southern Sudanese Boys, commonly known as the Lost Boys Many South Sudanese refugees dream of one day returning back to what most termed as their ‘motherland’.7 However, this dream was short lived. Before most could even set foot in their ‘motherland’, a major obstacle emerged that interrupted their return. In December 2013, the newest country in the world plunged into yet another conflict between the Southerners (tribal/ethnic groups). This conflict has been termed a ‘civil war’ by some international monitoring agencies.8 Once again hope was lost. This ‘civil war’ has continued into the better part of 2017.9

As indicated above, the road-map of this study goes back to events starting in the 1980s. In the late 1980’s, more than 33,000 Boys were forced from their homes due to outbreaks of violence in southern Sudan. The Sudanese (Islamic/Muslim) government attacked the rebels in the south, killing civilians and enslaving young girls. Young Boys, who took herds of cattle out to the grazing fields, were instead forced to run for their lives. The journey of these young Boys, who managed to survive, began with them migrating from Sudan. They joined together in small groups and made their way first to Ethiopia, back to Sudan, then to Kenya.10 The International Red Cross, which found them as they walked to Kenya, named them the Lost Boys since they arrived in Kenya unaccompanied by their parents. The Boys were named after characters from the story Peter Pan. More so, these Boys didn’t know whether their families were alive or dead. The phrase Lost Boys was used to identify those who didn’t know where their families were. The international agency, United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR), took them to the Kakuma refugee camps in northern Kenya. While at the refugee camps, these Boys were housed, fed, medically treated, and modestly educated from primary to high school.11 By the time they reached the refugee camps, they had walked nearly 1,000 miles. Approximately 10,000 Boys of the original 33,000, who started the epic journey, arrived in Kenya.10 It was here, that they were prepared for the long journey of resettlement in the U.S. in 2000.

The resettlement and eventually integration of about 3600 Sudanese Lost Boys, by the U.S government and Red Cross in 2000, was aimed at providing the Lost Boys with education and an environment in which they would overcome trauma.11 In the process, they would also be shielded from being victims of child soldiering in Sudan.3 The recruitment exercise was expected to go on for the rest of the Lost Boys, but was brought to halt by the terrorist attacks on the United States in September 11th, 2001. Bixler11 says, “about 100 of the 3,800 Boys were still waiting to be interviewed after 9/11” (p.133). The resettlement of the refugee South Sudanese Lost Boys started with arrival of small groups arriving in 2000. The resettlement criterion was based on their ages unaccompanied by their parents or families. The International Rescue Committee, through their director in (2014), stated that since most of the arriving Lost Boys were deemed to be over 18 and thus considered young adults, they did not qualify for foster care, "We placed the older boys together in apartments to try to maintain the kind of support network that they developed throughout their difficult journey and while living in the Kakuma camps in Kenya”.12 Most of these Boys however, didn’t know their birth dates and were randomly assigned an age (minors or legal adults) by the U.S. government/UN to facilitate their resettlement process.10 When physically examined in the refugee camps, the “Boy” who did not know their ages were given January 1st as their birth date. The intent was make them eligible to receive U.S. government benefits for unaccompanied minors.13 As stated above, the resettlement of the refugee Lost Boys was done in two categories (according to their assigned ages). The first group consisted of those who were 18 years or younger and were considered young. This group was resettled as minors. They were placed foster families who assisted them with going to school. The second group consisted of those who were 18 years and older. They were considered young adults. They were placed in apartments; and they were supposed to get jobs to start paying their bills. This group was not given a chance to immediately to go school after resettlement .

The demographic age resettlement arrangements immediately raised unforeseen challenges. Minors were placed with foster families where they received social and educational support. Those resettled as legal adults had to secure employment immediately to fend for themselves. They were provided with apartments rent–free for three months, but had to start paying rent thereafter. Once they began working, they were expected to repay certain medical expenses and the purchase price of airplane tickets that allowed them to leave Africa. Some Boys found it necessary to work two or three jobs, in order to raise enough money to pay their bills and remit support to their families back in Africa.2 They also learned that acquisition of English language skills was primary to secure even a manual job in the U.S., not to mention lack of previous work experience as most hadn’t worked in Africa.2

Their Expectations after Resettlement in America Finding a safe sanctuary, an education, and a job was of the utmost importance to every participant in this study. Muhindi et al.15 research support this finding by concluding the Lost Boys needed to find a safe environment in the U.S. in order to move freely, express themselves without fear, and to realize their educational and career dreams. They all hoped to get well paying jobs which would enable them to build their socio–economic upward mobility, and also send money back home to help those left behind. Once resettled, the US government and Red Cross planned to give the “Boys” an education while allowing them to heal from extremely severe trauma.12 Muhindi et al.15 findings indicate however, (after 20 interviews with the Lost Boys) although the Lost Boys arrived with high expectations of immediately going to school and becoming professionals, the majority of them (legal adults) had to adjust to the reality of postponing going to school and instead worked to pay bills while also saving money for college. They were disappointed to find that they would not be attending school as they expected to do prior to their resettlement in the United States. One Lost Boy said that he had expected to go to school the same day he arrived in the United States. What he did not known was that he was resettled as a refugee and not as a student. It was only after living for fourteen months in Boston that he finally got into school. Other Boys also expected to find people to help them go to school straight away after they arrived. Muhindi et al.15 quoted one Boy as saying, “I see things differently now that I have arrived in the United States. I now know that I can only get education through struggling” (p.9). Another said if he had stayed in Kakuma Camp, he would have attended high school by then, but in Boston he went to work instead. "All I wanted to do was set my mind on school. Yet I am not able to go to school because, if I go, who will take care of my other concerns?" (p. 9).

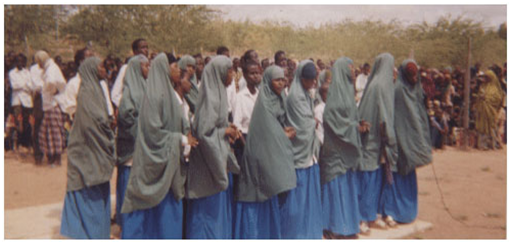

The Boys, who had a chance to go to school, discovered that the learning facilities in Sudan, Kenya, and Ethiopian refugee camps could not equal those that are in the United States (Figures 1–3). Learning facilities in the U.S are well equipped with buildings which have electricity, computers, and other classroom technologies. One of the participants had this to say after receiving a donation of a computer from his American friend: “This computer is magic in itself. Here is an instrument which did not only make writing easy but also spell checked English grammar for me. This is for the educated. I feel I belong to this class now and not to my semi–educated friends in Kakuma refugee camp who have never touched a computer keyboard in their lives”.2

Figure 1 UNHCR partner officials and I during refugee education day at Dadaab refugee camp in Kenya (1999).

Figure 2 Refugee students at Dadaab refugee camp in Kenya. They recited a poem on the value of education on education day. This event was sponsored by Care-Kenya in 1999.

Figure 3 Refugee students at Dadaab refugee camp in Kenya. They were acting out a play on the value education during education day. This event was sponsored by Care-Kenya in 1999.

In traditional Sudanese culture, adulthood meant marrying. To get married, one needed to pay dowry. Since most Lost Boys had no families to provide them with dowry, the only way to acquire dowry in the future was through education in the U.S. Education eventually could get them a job which could give them cash for dowry. In short education was a process to successful life.4 The Boys learnt quickly once they had an education, they could be able to get a job and save money for a dowry.

Interestingly, some Lost Boys did not have a chance to be resettled in the United States through the U.S government and United Nations program. Some are making wonderful academic inroads in refugee camps in Kenya instead. For instance, in March 28, 2012, the New York Times wrote a story about Paul Lorem, who is a Sudanese Lost Boy. Lorem, who had been a refugee in Kenya, sat for the Kenya National Examination Certificate (KNEC) in 2011. He earned the second highest scores in the national examination, which landed him in one of the top high schools in Kenya. He later transferred to South Africa, and finally ended up at Yale University in the U.S. He is determined to make it in life through education. As Nicholas Kristof, from the New York Times writes, “Education is the grandest accelerant for human potential”.16 Kuol Tito Yak, a 16 year old Sudanese Lost Boy, is another example. He was ranked fourth overall out of 776,214 candidates in the Kenya National Certificate of Education.17 His school principle said that Kuol skipped several classes because he was too bright for those classes. This in turn made him graduate early.17

Haines18 states that refugee economic self–sufficiency is the principle goal of U.S refugee resettlement policy, as stipulated in the Refugee Act of 1980. This self–sufficiency principle is embedded in, “The Federal Refugee Resettlement Program to provide for the effective resettlement of refugees and to assist them to achieve economic self–sufficiency as quickly as possible after arrival in the United States”.19 To effectively execute this refugee policy, the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) was forthwith established under the Department of Health and Human Services.19 Section (1) (A) of the Refugee Act stipulates the duties of the ORR Director as:

These stipulations are consistent with agencies that assist refugees with resettlement objectives; for most, employment is seen as a way to end dependence on government/sponsors and the welfare system. This is done by empowering refugees with an education, which in turn enables them to access and penetrate the U.S. job markets.

This study stresses the importance of hearing from the Lost Boys themselves. The study assesses individual assimilation process by applying Bourdieu’s cultural capital theory. Harker20 defines cultural capital as non–financial social assets that promote social upward mobility beyond economic means. This includes: education, intellect, style of speech, dress, and even physical appearance.20 The concept of cultural capital has recently been used and popularized around the world by researchers and scholars in relation to educational systems. Cultural capital was first introduced by a French sociologist, Pierre Bourdieu.21 Pierre Bourdieu first used the concept of cultural capital to study differences in outcomes in school performances of students from different class backgrounds and immigrants in the French educational system. His main hypothesis was to explore social class reproduction through family, school, and the state.21 Bourdieu made an argument that the culture of the dominant group is transmitted to students in learning institutions and therefore, embodied schools. This eventually led to social reproduction and is legitimized.22 The legitimization of education as a cultural capital allowed those who have acquired academic qualifications to enter the labor market, eventually enhancing their economic capital. Those who did not acquire academic qualifications were disadvantaged. I would agree with Bourdieu’s assertion. From primary investigations on the ‘South Sudanese Lost Boys’, there was a clear reverse trend in terms of acquisition of education (cultural capital) of the young Boys (minors) since their resettlement more than a decade ago. The Boys that were resettled as legal adults seemed to struggle with balancing work, learning the English language, and getting an education since their resettlement. The boys who were resettled as minors were placed with foster families. This opportunity allowed them to start off as dependents and to learn English with proficiency from their foster families. Their foster families also enrolled them in school to help with their education.

Bourdieu explained the process of acquiring cultural capital through his definition of habitus as “a system of durable and transposable dispositions which functions as the generative basis of structured, objectively unified practices”.23 These practices facilitate an individual’s position and self–esteem in a social space. Therefore, to Bourdieu, the habitus is a means which facilitates an individual’s position in a socio–economic social environment. Race, class, language, and ethnicity can be included in the habitus in determining an individual’s position in a social environment. For the refugee Lost Boys in Kansas City area, “race habitus,” “ethnic habitus,” “language habitus,” and “class habitus” will be the main factors that define them. That is, where they originate from and how they go around in their daily lives in the social space. Bourdieu's theoretical framework allows us to see the process of assimilation of the Sudanese Lost Boys in Kansas City area. A process of acquisition of cultural capital with various outcomes in terms of economic status, class, education attained, and expectations of each ‘South Sudanese Lost Boy’.2 Therefore, the concept of cultural capital is a tool that makes it possible for us to understand the individual Lost Boy’s positions in the social space, and how they arrived to those positions.22

Bourdieu also identifies three types of cultural capital. First is what he called embodied, in which the mind and the body of an individual are incorporated. Second is what he termed as an institutionalized state in which educational qualifications and achievements are very important. Third is what he termed as an objectified state in which an individual accumulates materials such as books, artifacts, dictionaries, and paintings.24 For the Sudanese refugee immigrants in the Kansas City area, it would be important to explore how each individual Lost Boy has applied the cultural capital model to elucidate their American experiences.2 For them, the social space is the stage of competition between the dominant and subordinate symbolic systems. Therefore, the area in which they resettled can be part of the social space in which the refugee Lost Boys come in as actors and live side by side with Americans. This mutual living side by side with the locals in the Kansas City area is facilitated by their indigenous culture from the Sudan (habitus). That is living in communities which translated into new cultural practices in the U.S. thus enhancing the refugee’s easy acculturation and assimilation process.2 This type of mutual living can be understood from Bourdieu’s point of view as “sense of one’s place” and a “sense of the place of others” in the social environment.24 For each Lost Boy, each one’s accessibility to social and economic resources will enable him to attend school in America while eventually acquiring institutionalized cultural capital (education). For Bourdieu21 and Bourdieu,22 the institutions in the United States provided a means in which the Lost Boys acquired social capital. For instance, the American credit system has enabled the Lost Boys to be financially stable. It has also allowed them to buy goods and products that they would have been unable to afford back home in Sudan or Kenyan refugee camps. It was through these institutions, including schools and familial structure, that the Lost Boys acquired cultural capital such as education. To Bourdieu,21 schools provided a source of transmission of America’s valued culture which is education. Through acquisition of education in schools as cultural capital, the Lost Boys converted their acquired cultural capital into economic capital by securing employment and earning an income.

Acquiring cultural capital in schools is not easy and straight forward. It is accompanied by what Bourdieu terms “social class.” Students from the lower class are easily “eliminated” from continuing with education to higher levels because of “economic issues” that accompany the learning process. Therefore, only a small number of students from the lower class manage to achieve academic success.21 Bourdieu’s ideas can be extended to the Lost Boys. This study found that unaccompanied refugee Lost Boys labeled as minors at the time of resettlement integrated more “successfully” than those resettled as legal adults. Minors received certain advantages over Boys who were labeled legal adults. Over time, those that resettled as minors acquired American cultural capital which helped them acquire an upward economic social mobility. Those who resettled as legal adults fell behind. The findings highlighted problems associated with age–based treatment of the Lost Boys (minors), and those who were arbitrarily classified as adults. Assigned ages significantly impacted their assimilation process into American society. Unlike those Boys resettled as minors, legal adults did not have access to structure and immersion opportunities afforded by foster families, formal education, and social activities. More so, INA: ACT 411 FN 1 Sec. 412. [8 U.S.C. 1522] section (1) (B) of the Refugee Act stipulates that, “employable refugees should be placed on jobs as soon as possible after their arrival in the United States”.19 Therefore, most legal adults did not have the opportunity to go to school and get an education like their counterparts (minors). As stated earlier, they were also required to pay back the bills they incurred during their process of resettlement.

The Sudanese Lost Boys arrived in the United States in 2000. Some of them currently live in the greater Kansas City area. More than a decade later, I want to examine their educational experiences in the Mid–West. This study uses social capital theory to assert that parental care and education are important factors in shaping the well–being and upbringing of children in a given society. Because these Boys were not accompanied by their parents when they arrived in the United States, it was important to find out how they adjusted to the new culture.

It is important to give this study an ethnographic approach given cultural elements (language, beliefs, values, and practices) of the Lost Boys are included in this study to enhance understanding of the processes of integration, assimilation, and/or marginalization of these Boys. Harris M et al.25 defines ethnography as "a descriptive account of social life and culture in a particular social system based on detailed observations of what people actually do." Hammersley et al.26 go a step further to say ethnography refers primarily to a specific method or set of methods used in research or study. This study draws from Ager et al.27 demographic and cultural/ethnographic criteria. Examining key human development indicators to elucidate the relative degree of assimilation of each participant Lost Boy since their resettlement in 2000. This indicator included whether the Lost Boys were employed, had an education, had acquired English language proficiency, participated in community activities such as politics and sports, had become U.S. citizens, participated in U. S. cultural activities, and practiced religions.27 Though the two scholars caution that achievement in any of the above indicators does not necessarily suggest successful integration, but rather serve as means to achieve integration.

I opt to use qualitative research methods in this study. Rather than seeking validation, this study seeks to retain the rich original data in detail. In this study, purely quantitative methods are unlikely to elucidate the raw primary data necessary to address the research problem. Although both qualitative and quantitative studies seek to explain causal relationships, the latter is more variable–centered. Also, since this study is based on open–ended questions, it makes sense to apply qualitative research tools. Furthermore it is hoped that an interested quantitative researcher will be able to take the conceptual tools developed in this study and apply them to isolate relevant variables in future research.

This study applies a multiple case study model, which provides the methodology for collection of data from randomly selected participants.28 The study employs an information–oriented sampling technique (snowball) in which the participants refer or name their friends or other individuals in the population as potential interviewees.29 This technique enables me to get 40 participants. Data used in this study was collected on July 25, 2009 from the participating Sudanese ‘Lost Boys’ in the greater Kansas City area. Primary investigation with the ‘Lost Boys’ participating in the study indicated that there were about 100 ‘Lost Boys’ living in the greater Kansas City area (this number was not verified because official data was not available). All participants were 18 years and above at the time of their respective interviews. The interviews were conducted at the residence of one participant, who was attending Johnson County Community College. He also acted as the liaison for the study and coordinated interviews held in his home. Data collection protocol for this study included in–depth and standard unstructured interviews, life stories, participant observation, informal conversation, and spending time with the ‘Lost Boys’.

The interviews were conducted face–to–face in English, while being recorded (later transcribed and analyzed). Face to face interviews allowed for the collection of observational data, such as facial expressions. Each interview ranged from half an hour to over two hours, with the majority being around an hour and a half. Although using an interview schedule, this study was flexible enough to allow the participants’ time to reflect and then answer (not rushing their responses). Though some participants did not respond to all questions posited to them, it remained important to make sure that further information was harnessed by making follow ups at the end of the interview. Since the study used open ended questions, it took a two–way communication where the interviewee asked for more relevant information when needed. The same questions were asked repeatedly to each participant and a saturation point was reached at 40 face–to–face interviews. This prompted the end of the interview process (reliability).

After conducting interviews with the Lost Boys, I transcribed the digitally–recorded interviews and used the data as the primary research source. I assigned the responses in a coded form, where respondents were just called participants instead of using their real names. I employed a thematic system using Ager et al.27 demographic and cultural/ethnographic criteria for my data analysis and identified common themes. A thematic system protects the confidentiality of individual participants instead of presenting individual cases. (Confidentiality of the participants in this research was of great importance, as they demanded this type of protection.) A table was designed,2 where I developed the major themes and sub–themes, which I later transformed into categories. In this case, all data was classified according to the main themes and sub–themes. A multiple case study framework was used to analyze the 40 cases. From the common themes, I derived sub–themes. The sub–themes were based on the level of education a given participant had achieved: high school diploma and/or college degree. The type of education they received was sometimes reflected in the type of job or employment secured by an individual.

However, this did not mean that those who were highly educated and had better jobs made more money than those who did manual work. Some manual jobs paid incredibly well. Those working as mechanics, in construction, and/or electricians all commanded a high hourly wage. According to Berg30 and Wolcott,31 each cautioned researchers against drawing hasty conclusions and suggested that researchers should conduct open “coding.” This would not only lead to “opening the inquiry widely,” but, also, as Wolcott put it, keep breaking down elements until they are small enough units to invite rudimentary analysis, then begin to build the analysis from there”.31 As stated by Eisenhardt,32 if all participants or most participants provide similar results then there exists substantial support for the development of a preliminary theory that describes the phenomena (validity). Three major themes emerged during this study and recurred among nearly all participants from the above eleven categories mentioned earlier. Education (cultural capital), Employment (economic empowerment), and, Citizenship (naturalization). Participants are then categorized into three themes depending on the social capital they possessed at the time of the interviews.

To reiterate, education is viewed as crucial to successful life and is highly valued as a core cultural capital in the U.S., while it has been given low priority in countries such as southern Sudan.33 Brophy asserts that, “the education system in Southern Sudan has always been under resourced”.7 The South Sudanese culture puts high value in rearing of animals over western education. For a long time the Sudanese government under resourced education in the south fearing social, structural, and political empowerment in the South.7 It is impossible to overstate the importance of education as a social capital, especially in Africa. The ‘Lost Boys’ were acutely aware that education in the U.S. was the primary means of securing a good paying job and thus a good life. Without overstating, education remains one of the most important tools of societal and human development. It is through education that individuals and societies achieve economic and social progress.34 It enhances individual integration (i.e. getting a job) that leads to self–sufficiency”.35 For the ‘Lost Boys’ this was a way to recapture control of their lives, which had depended so long on other people and organizations mostly in Africa.2

The Lost Boys came to the United States with a strong desire to acquire education and professional skills that they did not have an opportunity to get in Sudan. Academic qualification was partly a criterion used for resettlement in the U. S. by recruitment and resettlement agents. The first group of Lost Boys was resettled in the U.S. with some education as minors. They had not learned English as they were instructed in Arabic while living in Egyptian refugee camps. Therefore, acquiring proficiency in the English language was considered ‘vital capital’ for the refugee Lost Boys in the U.S. With the help of resettlement agencies, this group was placed in foster care and enrolled in schools as they were identified as minors according to U.S. laws (18 years or younger). The second group arrived in the U.S. without any English language skills or proficiency. They were expected to work upon arrival in the U.S. since they were considered legal adults under U.S. law (18 years and older). The third group consisted of ‘Lost Boys’ who arrived in the U.S. with elementary or high school education from Africa. While very few participants attended school in Sudan, all the participants in the third group received some education at refugee camps in Ethiopia or Kenya. While at refugee camps, they studied English. Once resettled in the U.S., some pursued further education while others looked for jobs and began working.

The first group

Eight participants were classified as minors upon their arrival in the U.S. and were subsequently placed in foster care. Five out of eight had acquired some form of education in the refugee camps in Africa. More so, residing with foster families gave them an early opportunity for acculturation. For instance, foster families assisted them in improving their proficiency in English, paid tuition, provided housing, and helped them with other daily living expenses. In American schools, they learned to discard capital that was not useful (e.g. holding hands that could lead to discrimination from American students and potential employees mistaking them to be gay). They replaced it with higher–valued capital in the U.S. like keeping time, being efficient, and becoming successful. They also learned to maintain high levels of hygiene (i.e. brushing teeth, wearing deodorant, and disposing of trash in designated places only). The following participant stunned me with his level of language proficiency: I can say I was very lucky to be placed in a foster family. I learned a lot through the family. They showed me a lot about American life and values. They took care of me when I was sick, paid my tuition, and bought food for me. I thank them a lot.

The second group

Eight participants in this study, considered legal adults, had not acquired English language skills prior to resettling in the U.S. This group of ‘Lost Boys’ went through the refugee camps in Egypt and were instructed solely in Arabic. This group faced greater challenges when learning English, obtaining work, and integrating with Americans. They even faced challenges with other African immigrants because they didn’t share a common language. They felt isolated from the rest of mainstream American society.

However, by the time of this study, I found that nearly all of the ‘Lost Boys’ who lacked significant proficiency in English were enrolled in English as a Second Language (ESL) courses in Kansas City. With some hard work in their studies with the English language, they hoped not only to communicate with Americans, but also with other nationalities present in the U.S. The following participant described great challenges when trying to speak English proficiently: Yea, it is difficult to get job because people from Kansas don’t trust you. Some people, they don’t need somebody who don’t know English. That one is difficult. They are good people but problem is English. You don’t know how to speak good English, you don’t want to write good English, some people don’t trust you. That one is difficult.

The third group

Twenty–four participants, considered legal adults, went through the Kenyan refugee camps of Kakuma and had received English instruction in both elementary and high school subjects. This group of ‘Lost Boys’ joined institutions of higher learning in Kansas City after resettling in the U.S. Some of them had graduated from a two–year program of study and were working, although they looked forward to furthering their education as one participant explained: In future, if I will be settled down well, I would like to continue my education to a Masters level. After settling down and having like a family or some You know what (light moment), life is not easy. You have a family!

By the time of this study (more than ten years after resettlement), nearly all participants indicated they were no longer receiving any educational support from the U.S. government, religious organizations, or other public organizations. They worked, attended school, paid their own tuition, and education–related expenses. Those that were placed in foster families had an advantage because their respective foster families helped pay some of the educational expenses. More so were easily exposed to the English language. Interactions with those families and their children increased their skills with the English language. A privilege not available to legal adults. For the minors, going to college after graduating from high school was a better choice. Thus, this increased their chances of economic success and upward social mobility (Author Citation). Those who had become U. S. citizens or permanent residents had the advantage of being able to apply for and secure federal student loans, as many American students do. Some ‘Boys’ said they had acquired a partial scholarships to help them. “Refugee children are eligible for public education in the same way as other children in the U.S., and many states receive federal funding to implement specialized educational Programming for refugee children”.36

On the other hand, the process of acquiring English language for those that were resettled as legal adults, was long and challenging. This also had a direct impact on their hiring process as most employers were hesitant to hire refugees who did not speak English. More so, it affected the academic performance for those who were enrolled in schools.2 Eventually delaying their graduation leading to low self–esteem. Legal adults also seemed less motivated to continue with college education which seemed expensive, thus affecting their acquisition of institutionalized cultural capital.2 In her research, Donkor37 indicated that it was lack of English proficiency that had led some Lost Boys to be marginalized by the American society. This caused them to only interact with other Sudanese refugees in ethnic enclaves, which provided both emotional and social support.

It is clear from this study that “successful” integration for the Sudanese refugee Lost Boys required an education. Education played a key role in acculturation and integration of the Lost Boys. Without education and language acquisition, the Boys had little hope of securing desirable employment, financial stability and/or prosperity, or acceptance into American social groups. For the Lost Boys in general, going to school in America and acquiring cultural capital varied according to age and interaction with Americans. The variations were clearly seen amongst those that were resettled as minors and those that resettled as legal adults in terms of their proficiency in English and assimilation (Author Citation). Bourdieu21 & Bourdieu22 would argue, the institutions in the United States provided a means in which the Lost Boys acquired social capital. In particular schools and family enabled the Lost Boys to gain cultural capital, such as education.

To the ‘Lost Boys’ in the greater Kansas City area, learning and acquiring English language was part of acquiring cultural capital. Thus, this determined the relationship between the dominant American society and the Lost Boys in the social space.23 In Africa, the type of education that the Lost Boys (those who had an opportunity to go to school) acquired was not English language intensive to allow fluency, use, and mastery of the language. The more the Lost Boys were exposed to English language in the American society, the more it became natural to them and thus its usage. Eventually this led to substituting their Sudanese language for English and strengthening their relationship with the American society.2 Bourdieu24 would argue that incorporating elements of American cultural practices, that the Lost Boys acquired in learning institutions and social interaction with Americans, determined the relationship the Lost Boys had with Americans in the Kansas City area (helping them form inter cultural social networks). If not, they would likely be marginalized or excluded from the mainstream Kansas City community. Interviews with participants in this study indicated, that nearly ten years after resettlement, most Boys with low levels of education and language proficiency tended not to integrate well into mainstream society; and for the most part they lived in ethnic enclaves. It was encouraging to learn that most of those who had faced language challenges were learning English language by attending schools that taught English as a foreign language (ESL).

In this case, they could be said to be on the integration process because institutions of learning are integration facilities. Conversely, Boys with high levels of education and language proficiency had integrated into mainstream U. S. society. They had jobs, where some were even supervising Americans working under them. Though I did not meet personally with those who had become highly successful in this study, other sources that I referred to indicated that some Boys around the U.S. were becoming very successful. For example, Daniel Geu38 from North Dakota State University and Gabriel Deng from the University of Missouri at Kansas City joined the military and were training as army officers at cadet ranks. After their successful training, they were going to command assigned army American units (Figure 4). Gabriel Deng is now a U.S army captain.39 According to his LinkedIn profile, Daniel Geu Brigade is a Senior Human Resource Manager for the U.S. Army in Killeen, Texas. An annual report published for the U. S. Congress in 2003, by the Office of Refugees and Resettlement (ORR), indicated that the Lost Boys (minors to be specific) had responded well to their resettlement program and that included enrolling and attending schools. At the time of the report, 65 percent of the Boys were attending school and 79 percent were becoming fluent in English.19

None.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

©2017 Mabeya. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.