eISSN: 2572-8474

Research Article Volume 6 Issue 3

1Department of Medical and Health Sciences, Division of Nursing Science and Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Linköping University, Sweden

2Department of Medical and Health Sciences, Division of Nursing Science, Linköping University, Sweden and Centre for Clinical Research Sörmland, Uppsala University, Sweden

Correspondence: Rose-Marie Isaksson, Department of Research, Region Norrbotten County, Luleå, Sweden, and Division of Nursing Sciences, Department of Medical and Health Sciences, Linköping University, Robertsviksgatan 7, S-971 89 Luleå, Sweden, Tel +4613281000

Received: May 08, 2019 | Published: June 20, 2019

Citation: Hjelm C, Andreae C, Isaksson RM. From insecurity to perceived control over the heart failure disease–A qualitative analysis. Nurse Care Open Acces J.2019;6(3):101?105. DOI: 10.15406/ncoaj.2019.06.00191

Aims and objectives: The objective in our study was to explore chronic heart failure patients’ perceived control over their heart disease.

Background: Higher levels of perceived control over one’s chronic heart disease are associated with lower levels of psychological distress and a higher quality of life.

Design: The study has an explorative and descriptive design using a directed manifest qualitative content analysis according to Marring.

Methods: The analysis was based on nine interviews with four men and five women aged between 62-85 years, diagnosed with chronic heart failure. The study followed consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ).

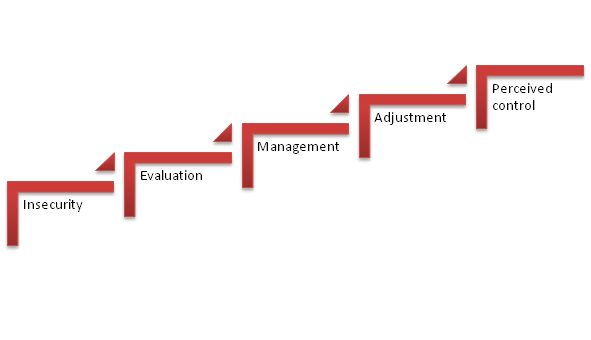

Results: Five categories emerged in the analysis, mirroring a step-by-step process. The first step, insecurity, was followed by evaluation, management and adjustment. The patients finally reached a higher level of perceived control over their lives in relation to their heart disease.

Conclusions: Most of the patients stated that they could assess and manage symptoms and had adapted to their condition, which increased their level of perceived control.

Relevance to clinical practice: These findings suggest that managing symptoms is important for strengthen the patients with chronic heart failure. The findings can help health care professionals in communication with the patient planning for self-care actions.

Keywords: control attitude scale, heart disease, heart failure, perceived control, self-care

Millions of older people worldwide suffer from heart failure (HF).1 The estimated prevalence of chronic heart failure in Sweden is 2.2%, incidence 3.8/1000 person-years, and mortality 3.1/1000 persons-years.2 There is no cure and so the cornerstone of the treatment is to reduce symptoms and improve quality of life and survival. Heart failure (acute and chronic heart failure) guidelines recommend that health care providers advise and educate patients to perform self-care.1

Background

Accordingly, health care professionals need to recognize barriers, facilitators, skills and behavior related to performing self-care. Promoting self-care is a challenge for health care professionals and patients. Numerous patients with HF do not perform sufficient self-care. Barriers include comorbidity, older age, and psychosocial factors. Furthermore, patients’ behavior in terms of having control over their disease may be a part of the reason for performing inadequate self-care.3,4

Perceived control involves the individual’s belief in the ability to cope with events to achieve health-related outcomes.5,6 It has been found that levels of perceived control are associated with levels of psychological distress. Patients with a high level of perceived control are less likely to have symptoms of depression and anxiety than patients who experience psychological distress.7−13 Perceived control has a positive impact on the decrease of emotional stress and on symptom distress in palliative care and in patients with symptomatic HF.5,14

Perceived control is a fundamental construct for predicting how successfully patients will adapt to cardiovascular diseases.5 Therefore, perceived control might be a possible target for nursing interventions in order to expand the knowledge of self-care in chronic heart failure. However, the way patients with HF perceive control over their heart disease, focusing on their lived experience, has not been investigated.

Aim

The aim of the present study was to explore chronic heart failure patients’ perceptions of their control over their heart disease.

Methods

Study design and sample

This qualitative interview study has an explorative design with a purposeful sampling. In total, nine patients (mean age 76, SD 8.9; four men (mean age 72, SD 10,9) and five women (mean age 80, SD 6,3); chronic heart failure duration New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III-IV for 1-5 years, were invited to participate. All participants were provided with written and oral study information, and they gave informed consent to participate. The participants could whenever they wanted withdraw the consent and all data was treated confidentially. The study followed the COREQ guidelines.15 The COREQ guideline is a checklist which aims to promote complete and transparent reporting among researchers and indirectly improve the rigor, comprehensiveness and credibility of interview and focus-group studies.

Data collection

Patients with chronic heart failure (CHF) were recruited from outpatient heart failure clinics at a university hospital in the south of Sweden. Patients aged 18 years and older who were diagnosed with CHF according to the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines16 were recruited to the study by HF nurses. None of the patients had assistive devices. Every patient lived in their own homes mostly in flats and everybody had a partner. Patients with a history of severe psychiatric illness, neurological disorders, i.e., Alzheimer’s disease, vascular or mixed dementia, drug abuse, short expected survival or difficulties with reading and understanding the Swedish language were excluded.

The participants chose to be interviewed at their homes and the interviews took place from March to August 2009. To obtain rich and narrative responses about the topic, the interview guide was based on the validated instrument Control Attitudes Scale Revised, developed by Moser et al.17 The participants in this study responded to five open-ended questions:

Data analysis

The interviews were analyzed using a direct manifest content analysis according to Mayring´s approach.18,19 The aim was to explore chronic heart failure patients’ actual experiences of perceived control, and for this purpose a qualitative content analysis was performed20 with first a deductive approach followed by a inductive approach.21 The procedure began deductively by formulating questions, derived from a theoretical background with a validated instrument Control Attitude scale Revised17 the research question determining the aspects of the material taken into account. Then, the material was worked through and five categories were tentatively identified, based on the interviews.

An inductive approach of content analysis is preferable when the purpose is to expand knowledge about phenomena.21−24 Therefore, a step model of inductive category development was used.20 The categories were revised and condensed to the main categories and controlled for reliability.20

Consideration of trustworthiness

The transcripts were read by all authors separately to ensure trustworthiness.20,22,24 The focus was to find differences and similarities according to the study aim. The interviews were then compared and discussed until consensus about the topic for the study was reached. The material was read through to explore the CHF patients’ perceived control of their heart disease. The first author listened to and read the interviews on several occasions before, during and after the transcription process. Thereafter, all the authors read all the interviews. The second and third author re-read the interview texts.

The interviews were analyzed in five steps, according to Mayring. In step 1, the texts were defined to select the parts that were relevant to the study aim. In step 2, the situation of the data collection was analyzed, e.g., how the texts were generated and who was involved. In step 3, the texts were formally characterized in case the transcribed texts had been influenced when they were edited. In step 4, the direction of the analysis for the selected texts was defined. In step 5, a theoretical differentiation was made by summarizing the data into categories. These categories were then paraphrased, and relevant passages and paraphrases with the same meaning units were merged (first reduction). Paraphrases that were similar to each other were bundled and summarized in a second reduction.19,20 When the explaining paraphrases were tested, five categories emerged, mirroring a step-by-step process leading to perceived control.

The analytical procedures were carried out in a distinct and transparent way with a summary, explication, structuring and interpretation of the material. This is a check of reliability to which the data analysis can be replicated. Validity was addressed by structural and sampling validity, how well the matrix for analysis reflects the concept to be studied.18 The preunderstandig among the authors all was registered nurses and researchers experienced in the research field and in the research questions. The authors did not have any previous personal relationship with any patient in this self-care context.19,24

Ethical considerations

The principles of the Declaration of Helsinki25 were followed and the Regional Ethical Review Board at Linköping University (study number Dnr 03-569) approved the study.

Findings

The analysis reached saturation and revealed that perceived control was influenced by the patients’ experiences of bodily symptoms. Five categories emerged, mirroring a step-by-step process. The first step, insecurity, was followed by evaluation, management and adjustment to finally reach a higher level of perceived control over one’s life in relation to the heart disease. The results are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Perceived control is when patients feel that they have control over their body and the symptoms and manage to handle them. They have then adapted to the disease. The figure shows the heart failure patients’ experiences of bodily symptoms in a stepwise process leading to all five categories.

During the analysis, the following explicating paraphrases emerged: affecting everyday life, handling the heart disease, having control or feeling partly in control. Body limitations played an important role in the process of changing from feeling insecure to perceiving control.

The CHF patients described that they experienced body limitations. They felt they did not have the same energy and strength as before; they were more tired and felt restricted. One patient said: “You can manage only half of the things that you managed before”.

The patients related these problems to being recently diagnosed with CHF, suffering deteriorations in symptoms, and/or being recently hospitalized. They experienced difficulties in optimizing medications. Some had problems with side effects of new medications. They tried to live as normally as possible, but experienced many bodily limitations that affected their life situation in physical, mental and social situations. One woman stated: “I like to meet people, it is the social part, meeting my family - the kids, grandchildren or friends - that I like so much. Now I do not have the strength for a fulfilled social life and I feel sad about that”.

Insecurity

Those recently diagnosed with HF felt helpless and insecure in everyday life, and they worried about many things. They did not want to travel or do the same things as before. Some of them could not go shopping alone, or take a walk with the dog.

There were many things they could not handle anymore. “I need help”, one patient said, “every day is a disaster, and you feel very ill when you come home from the hospital”. The patients always felt in need of help and felt that they were losing their energy. Most of them wanted to do more than their capacity allowed; they could not escape from the disease and the manifested symptoms, and they could not cope with stress. “Yes, it is about the disease. I can never escape from it; it is constantly on my mind. Those who had been diagnosed with HF for a longer period of time remembered the time immediately after being diagnosed and how difficult that situation was.

Evaluation

Evaluating one’s body refers to noticing changes in the body, e.g., edema. The participants felt that this increases control;” I have my reliable early signs; I check for swollen legs or other parts of my body”. The participants noticed changes in breathlessness and knew their limits, which gave them a feeling of control. Good laboratory values were seen as a sign that they were taking good care of themselves. Recognizing that others had the same disease and that other people had the same symptoms made the patients feel in control.

Managing their living situation and learning how to carry out the evaluation meant having control over their body and managing disease symptoms. This gave the participants control over their living situation, which in turn made them feel secure and strong. One patient expressed the situation like this;

“Breathlessness… I notice that immediately, and the swollenness - pretty obvious early signs…”

Other patients in the hospital with the same diagnosis provided information and comforted and supported those newly diagnosed, reassuring them that there was nothing to be nervous about.

Management

This category is about management to gain control over the body, and learning to handle the heart problem and gradually feel safer.

Management refers to actions that made the patients feel well, such as exercising instead of resting and lying in bed all day. The participants checked if their legs were swollen, took extra medications or drank less fluids, which gave them control over their body. They had their own ideas about what made them feel better in various situations. When they felt anxious, lying in bed and listening to music made them feel better. They needed to have someone with them when shopping and doing other activities. This support strengthened their management.

The participants felt that they had control when they did household work. Taking medications and temporary medications gave them control over their body. “It feels good to have something…you know…to have control over the household, as much as I can manage”.

Adjustment

The participants found it difficult to answer the question about helplessness. One patient stated: “I have learned to live with it and say thank you and take the day as it comes; there is nothing else to do”. This adjustment to learning to live with the disease was a way of trying to accept the situation. Some talked about how they could participate in the community with their children and grandchildren, and how they lived with "it", the disease. If they received help when needed, they did not feel helpless. They learned to handle other diseases such as diabetes and felt good about that. They could even do household tasks with a walker.

Several participants said that it was worse having the disease at a younger age, when they were working and had a family to take care of. Some felt old now, but they wanted to live longer. They did not talk about death but spoke indirectly about it.

“It was worse when I was younger, sometimes I wonder why I am standing here at 85 years old - it is enough. But when I get out of bed in the morning and get dressed, I think ‘a few more years’…”

They felt safe knowing that the medications were good for them; they could take a “pill” as a kind of backup, which gave them a feeling of control.

When they talked about the their younger years is when they were newly diagnosed, the past experiences over time gave them a better life situation and a feeling of having control and being able to adapt to the “disease”.

Perceived control

Perceived control refers to when the participants felt that they had control over their body and the symptoms and managed to handle them. Then, they had adapted to the disease. The steps (insecurity, evaluation, management, adjustment) towards perceived control made them feel in control over their symptoms. “I quickly notice swollen body parts, those are clear and early signs”. One patient said that “I take it as it is, I have my medication and it gives me control over my body”.

The aim of this study was to explore CHF patients’ perceived control over their own heart disease. It was found that the patients gained perceived control over their bodies through a step-by-step process moving from insecurity, evaluation, management, and adjustment and finally perceived control.

Body limitations are when patients struggle to take control and achieve body awareness, which gives them a form of control. Younger people who had recently been diagnosed and had more symptoms, such as fast or slow heart rhythm, felt insecure when they were in an acute phase of titration and change of medications. They struggled with monitoring their body, for example, to discover an edema and understanding that it is related to drinking too much water related to weight, or working out if their medications caused side effects. Riegel et al.26 have described processes of symptom perception that involve body listening, that is, the monitoring of signs as well as the recognition, interpretation and labeling of symptoms. According to Riegel et al.,26 self-care decisions are influenced by knowledge, skills, experience and values. In the present study, the participants talked about body limitation as a statement. They did not have a negative attitude and were not inconsistent in their self-care practice. Self-care monitoring is a process of routine, vigilant body monitoring, observation and body listening

The patients in this study felt in need of help and felt that they were losing their energy. Most of them wanted to do more than their capacity allowed. They could not escape from their disease and they could not cope with stress. The concept insecurity has not been expressed in prior studies or been shown to play a role in perceived control, but studies have shown that many patients with HF have physical and depressive symptoms, as well as an impaired functional status27,28 that could be related to insecurity. In this study, patients described evaluating their bodies, noticing changes and knowing their limits, which gave them a feeling of control.

They felt good and secure when they followed hospital recommendations with regard to medications or laboratory values. This is in line with the middle-range theory by Riegel et al. that states that self-care treatment may require consultation with a health care provider, depending on the message the patient is given by the provider about independent modification of therapies. The theory states that self-care maintenance involves an evaluation of changes in physical and emotional signs and symptoms in order to maintain physical and emotional stability.29

There was a distinct difference between those who had lived with their HF diagnosis for some time and those who had recently been diagnosed. Those who had recently been diagnosed with CHF experienced symptoms in symptom class New York Heart Association (NYHA) III-IV they felt insecure in their daily life and talked about feeling helpless. Those who had lived with HF in symptom class NYHA I-IV for some time had more experience and did not talk about feeling helpless. The lived experience of being a HF patient moved through different stages, depending on the patients’ NYHA class status. Two people said that they did not experience helplessness, but the underlying meaning can be interpreted as helplessness. Earlier studies have found that patients with low perceived control experience higher emotional distress (i.e., anxiety, depression and hostility) than those with high perceived control.5 Banerjee et al.8 reported that higher scores of health-related quality of life are significantly correlated with perceived control, depressive symptoms and anxiety. It is important for health care personnel to help patients with self-care actions, helping them to gain perceived control in this stepwise process (Figure 1).

Management and adjustment were steps in the process to gain perceived control. Patients worked to evaluate their body and their symptoms, and how to manage and find strategies if they felt ill. The participants described how they adapted to their heart disease and learned to live with it. According to a review by Welstrand et al.,30 patients appear to undergo processes of adopting a new identity, a “new self”. The new self could be perceptions of day-to-day life, coping behaviors, role of others, and concept of self.30

A study by Heo31 showed that perceived control was independently associated with health-related quality of life in CHF patients. The present study and other research show that perceived control is an appropriate target for nurses and other health care personnel to consider when supporting patients. Using this model can be helpful for finding out what stage patients are at in the process of gaining control over their bodies. The results of this research will be useful for the development of nursing interventions that can promote/strength perceived control in this population. Educational actions, by means of nursing consultations, can and should be used to empower patients to symptoms recognition, management and having focus on body limitations.

Studies that produce and synthesize evidence on interventions for perceived control management/maintenance in CHF patients are needed to guide therapeutic team decisions aiming a better quality of life for these patients.

Experiencing control over their bodies improves heart failure patients’ level of perceived control. Those who were recently diagnosed with CHF felt insecure and sometimes helpless in daily life and struggled with insecurity, as pointed out in the first step in the model. This could be useful information for improving self-care planning in this population.

Relevance to clinical practice

Findings suggest that managing symptoms is important for strengthen the patients with chronic heart failure. The findings can help health care professionals in communication with the patient planning for self-care actions. Our results could also be useful information for improving self-care planning in many patients groups. The new model can help health care professionals by increasing their understanding of the patients’ experiences in their communication with patients planning self-care actions.

None.

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

©2019 Hjelm, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.