MOJ

eISSN: 2573-2927

Research Article Volume 2 Issue 4

1Graduated Institute of Communication Engineering, Tatung University, Taiwan

2Department of Bioengineering, Tatung University, Taiwan

Correspondence: C Will Chen, Department of Bioengineering, Tatung University, Taiwan

Received: September 02, 2017 | Published: September 19, 2017

Citation: Hsu CY, Lee CC, Chu CF, et al. Analysis of yoga’s effect on health via electro meridian analysis system. MOJ Yoga Physical Ther. 2017;2(4):94-99. DOI: 10.15406/mojypt.2017.02.00027

This Study is the first investigation of yoga’s effect on the twelve main meridians of human body by the Electro Meridian Analysis System (EMAS). Through the three main elements of yoga’s breathing, asanas sequence and relaxing process respectively, we investigated the dedicated excitation on the twelve meridians by measuring the change of meridian currents. Participants were categorized into two groups; one group of participants was practicing yoga for more than one year (yoga senior group, YSG) and the other group was less than two months (yoga junior group, YJG). All participants were asked to practice yoga and then their meridian current was measured at 24 Ryodoraku acupuncture points in the twelve main meridians by EMAS before and after yoga’s lesson. Result of this study shows that in both of YSG and YJG, the average value of all of meridian currents (Amc) have increased, meanwhile, by pair samples t-test, there was statistically highly significant increase of Amc in YSG (p-value=0.0094). In addition, the significant increase (p-value <0.05) of meridian current for YSG was possibly in hand and foot meridians, but the significant increase (p-value <0.05) of meridian current was observed only in the hand meridians for YJG. The results show that yoga practice could stimulate the positive energy response for our body’s meridian system.

Keywords: yoga, asanas, meridians system, acupuncture, ryodoraku method

PLB, photoluminescence of bioceramic materials; BP, blood pressure; HRV, heart rate variability; HPA, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal; SNS, sympathetic nervous system; TCM, traditional chinese medicine; EEG, electroencephalography; tdcs, transcranial direct current stimulation; BMI, body mass index; YSG, yoga senior group; YJG, yoga junior group; EMAS, electro meridian analysis system

Human body meridians systems traditionally are believed to constitute channels connecting the surface of the body to internal organs. The meridian theorem hypothesizes that the network of acupuncture points and meridians can be viewed as a representation of the network formed by interstitial connective tissue.1 Based on results of the past study and our review of the literature, we suggest that the interstitial fluid concepts of the meridians and acupuncture points explains the reported transmission of current, acoustic responses, thermal responses, optical transmissions, isotope passages and photoluminescence of bioceramic materials (PLB) stimulation in meridians. The hypothesis that meridians are open channels of interstitial fluid seems to be acceptable, based on evidence-based research.2,3

Yoga is a mind-body practice from ancient Indian philosophy. Yoga and coherent breathing provides evidence that participants were associated with a significant reduction in depressive symptoms for individuals with major depressive disorder.4 Regular yoga practice may be recommended for women to cope with their depressive symptoms and stress and to improve their heart rate variability (HRV).5 Evidence is accumulating that yoga improves blood pressure (BP) control, with downregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and the sympathetic nervous system (SNS).6 By integrating yoga in therapy can be created to overcome existing impediment in current psychotherapy.7 Yoga practice has also been proved for improving older adults’ balance to prevent falling.8

In this study, we first assuming the possible connection between the meridian current (or energy) measurement and the physiological effects stimulated by the yoga practice. The meridian current measurement is based on the skin conductance at the specific acupoints. It was reported that skin conductance depends on current flow through skin due to an electro-osmotic effect and that the measurement of electro conductivity of Ryodoraku meridian points is a useful technique for evaluating sympathetic nervous activity.3 Ryodoraku method is widespread in Japan, where electro conductivity in dermatomes corresponding to the level of sickness is used to stimulate the acupoints or suppress it.3 Comparing with the Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) theorem, Ryodoraku acupoints are close to the “source point” of twelve meridians in TCM. The source points of meridian are considered as where the original energy (qi) of the visceral organs pours or stays.9 We have found the specific Ryodoraku acupoint’s current is indirectly affected by another meridian acupoint treated by the PLB irradiation. Because the meridian channels and their corresponding acupoints are located in distinct locations, typical light energy irradiation should not be able to affect the electrical resistance of the skin or other meridian channels if no interconnecting network exists.2 We found that PLB treatment on specific acupoints will result in the significant change of Amc measured from 24 Ryodoraku acupoints; besides, PLB treatment improved patient with benign facial tremor and normalized effects on Amc and meridian current levels.2,3 We have also studied the treatment of PLB with sound frequency (SF) on the specific meridian acupoints and found that there were a high percentage of subjects (91.7%) with increased electroencephalography (EEG) potentials between 15-27 Hz (beta-1 frequency band) and new application in the clinical problem of sleep disorders.10 Meanwhile, there were alternative treatments for sleep disorder, e.g. transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) treatment had been shown to increase beta-band power11 and transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) had been shown consistently evoked beta-band oscillations (13-20 Hz) in the parietal cortex.12,13 Therefore we proposed that the PLB-SF treatment on specific meridians could stimulate neuromodulation.

From the above review of studies, we realize that yoga practice could stimulate the reduction of depressive symptoms and stress, to improve their HRV or to modulate BP control with downregulation of HPA axis and SNS. We also learned that the treatment of PLB-SF on specific meridians will stimulate the change of all of meridian currents (energy), the neuromodulation, or improve patients with sleep disorders or benign facial tremor. Therefore, in this study, we propose the first investigation trying to find the possible connection of physiological benefit of yoga practice with the improvement of human meridian energy system quantified by EMAS technique.

Participants for yoga program

All participants for yoga program were volunteers recruited from the surrounding community. Sixteen participants were involved in this study. The demographic data of participants are shown in Table 1. To enroll in this study, participants had to be aged between 27 and 55 years old, have a limited range of body mass index (BMI), body weight and height as shown in Table 1. Participants were excluded if they were pregnant or nursing or had physical contraindications to exercise. The participants have been asked by our researcher to make sure they don’t have any above problems. To study the possible yoga practice time effect on the human meridian energy excitation, all of the participants had been divided into two groups: 10 persons in the yoga senior group (YSG) and six persons in the yoga junior group (YJG). The participants in YSG have practiced yoga for more than one year and the participants in YJG have practiced yoga less than two months. There are no significant differences (p-value > 0.05) of age, BMI, body weight and height between YSG and YJG as shown in Table 1.

Variables |

Total (n=16) |

YSG1 (n=10) |

YJG2 (n=6) |

p-value4 |

Females/Males |

16/0 |

10/0 |

06/0 |

- |

Age (mean±SD) |

42.7±12.8 |

44.3±14.3 |

40.0±10.5 |

0.534 |

BMI3 (kg/m2) |

20.6±2.4 |

20.9±2.9 |

20.2±1.5 |

0.548 |

Body weight (kg) |

50.8±6.5 |

50.8±7.6 |

50.8±4.8 |

0.992 |

Height (cm) |

156.6±3.8 |

156.4±2.3 |

158.5±2.6 |

0.115 |

Table 1 Demographic data of yoga participants

1YSG is yoga senior group that practiced yoga for more than one year

2YJG is yoga junior group that practiced yoga less than two months

3BMI is Body mass index

4p-values for t-test comparison of data from YSG and YJG

Yoga program

Both groups (YSG and YJG) received 50-60 minute sessions in accordance with the school program. Both YSG and YJG groups received the similar frequency and duration of instruction in their respective sessions. The yogic technique and flexibility training were taught by a yoga alliance certified instructors. The schedule for the yoga session is described in Table 2. Content for the yoga session was built on the knowledge and experience from the prior classes. General concepts were introduced and practiced early in the intervention, with progressively more poses and variations of instruction incorporated throughout the training period. Worksheets illustrating the postures were given to each student. During the class, discussion included ways to use yogic techniques outside of class or at home.

S. no. |

Yoga Class Program |

1 |

Session preparation (5-7 min) |

2 |

Breathing exercises (2-3 min): deep diaphragmatic breathing pattern: breathing from the lower belly, from the ribs and lastly from the upper chest |

3 |

Warm-up (3-4 min): moving connections between bones and major muscle groups |

4 |

Asanas sequences (approximately 30-40 min): e.g., tree; warrior I, II and III; balancing-half moon; mountain; chair; standing forward flag; seated wide angle; cobra; bridge; and rabbit |

5 |

Relaxation (3-5 min): corpse poses to release tension, distract from worry and be aware of breathing |

Table 2 Yoga Class Program

Measures

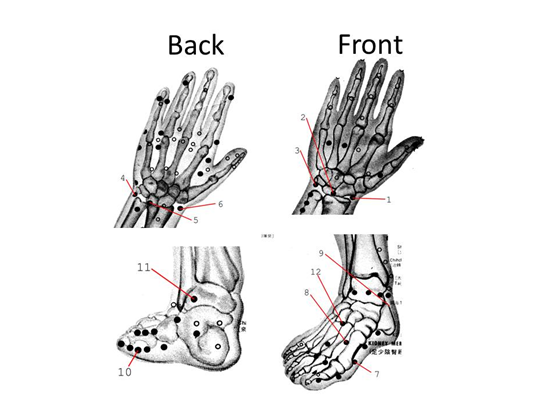

The meridian current (unit of mA) was measured by using an Electro Meridian Analysis System (EMAS) device (MEAD Me-Pro, Hanja International Co., Taiwan), which yielded electro dermal measurements of the 24 Ryodoraku acupoints (Figure 1): Lung (LU9), Pericardium (PC7), Heart (HT7), Small Intestine (SI5), Triple Energizer (TE4), Large Intestine (LI5), Spleen (SP3), Liver (LR3), Kidney (KI5), Bladder (BL65), Gallbladder (GB40) and Stomach (ST42) and was similar to the equipment used in the authors’ previous studies.2,3 The EMAS machine is composed of two electrodes: the first is a metal cylinder held in the participant’s left hand and the second is connected to a spring-loaded probe containing cotton moistened with physiologic saline solution. A trained technician applies the second electrode to the 24 acupuncture points along the 12 meridians (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Position of Ryodoraku acupoints (totally 24 points based on left and right sides of human body).

1. Lung (LU9)

2. Pericardium (PC7)

3. Heart (HT7)

4. Small intestine (SI5)

5. Triple energizer (TE4)

6. Large intestine (LI5)

7. Spleen (SP3)

8. Liver (LR3)

9. Kidney (KI5)

10. Bladder (BL65)

11. Gall Bladder (GB40)

12. Stomach (ST42)

Participants for the evaluation of EMAS stability were volunteers recruited from Tatung University, Taipei, Taiwan. Five participants were involved in this evaluation. The demographic data of participants are shown in Table 3A. The participants were measured their meridian current at 24 Ryodoraku acupoints, then measured again after about 30 min of mild activity. The comparison of the first and second measurement at same acupoint from same person was used to evaluate the stability of EMAS device.

Females/Males |

2-Mar |

Age (mean±SD) |

23.8±1.3 |

BMI (kg/m2) |

22.6±2.8 |

Body weight (kg) |

65±9.6 |

Height (cm) |

169.4±9.6 |

A. Data of participants

Variables |

1st Measurement |

2nd Measurement |

p-value2 |

Amc1 |

46.3±12.1 |

41.2±17.0 |

0.101 |

Lung (LU9) |

56.3±17.4 |

51.6±26.9 |

0.324 |

Pericardium (PC7) |

46.6±18.6 |

42.5±20.7 |

0.174 |

Heart (HT7) |

42.5±13.2 |

39.5±16.4 |

0.479 |

Small intestine (SI5) |

48.8±25.1 |

40.4±28.2 |

0.07 |

Triple energizer (TE4) |

56.4±21.8 |

50.7±27.7 |

0.238 |

Large intestine (LI5) |

51.8±16.0 |

46.9±22.3 |

0.437 |

Spleen (SP3) |

49.3±21.1 |

43.1±20.7 |

0.234 |

Liver (LR3) |

45.4±15.4 |

36.1±17.7 |

0.061 |

Kidney (KI5) |

33.2±17.9 |

27.0±17.6 |

0.158 |

Bladder (BL65) |

54.4±21.3 |

56.8±21.5 |

0.331 |

Gall Bladder (GB40) |

24.9±13.4 |

21.8±10.7 |

0.091 |

Stomach (ST42) |

46.0±16.2 |

37.5±13.5 |

0.0203 |

Table 3: Stability evaluation of Electro Meridian Analysis System

B. Repeated measurement of meridian currents (μA) without yoga practice.

1Amc is the average value of the meridian currents (24 Ryodoraku acupoints).

2p-value for pair t-test comparison of first and second measurements at specific Ryodoraku acupoints

3p-values for pair t-test comparison of first and second measurements at left and right sides of ST meridian were 0.224 and 0.063, respectively.

Statistical method

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 15.0 software (SPSS Inc., USA). We examined the individual variables by using means and standard deviations, exploring group differences by using independent or paired samples 𝑡-test.

Repeatable meridian current measurement before Yoga practice

The device for EMAS measurement maintains stable levels of current. This is advantageous because the overall current levels provide good reproducibility when the device is operated by a trained technician. Table 3 shows the repeated measurement of each Ryodoraku acupoints from volunteers without yoga practice. Table 3B shows that most of second measurements were slightly lower than the first measurements. Based on the pair-sample t-test, the p-values (Table 3B) for most of the meridian currents, including the average value (Amc) summarized from all of the Ryodoraku acupoints’ currents, are large than 0.05, means the insignificant difference between same acupoint from same person without yoga practice. There is only one meridian (Stomach, ST42) in Table 3B shows the slightly significant lowering (p-value=0.020) between the sequenced measurements. But if we separate the measurement at ST42 by left and right sides of human body, we will obtain the insignificant p-value of left and right sides as 0.224 and 0.063, respectively (Table 3). Therefore we consider the EMAS device could maintain stable levels of meridian current measurement from a specific person without yoga lesson but only mild and normal activity.

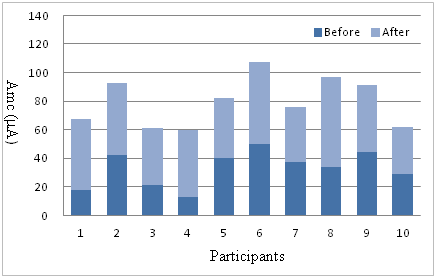

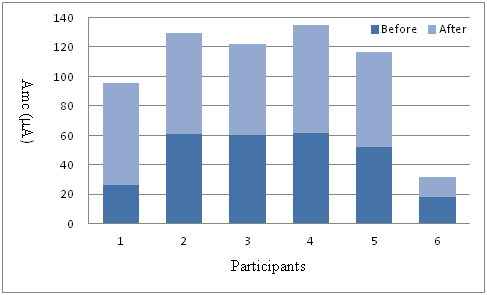

Results of meridian current change after yoga practice

Figure 2 shows that after yoga practice all of participants showed their increase of Amc. But after the statistical analysis of p-values, Table 4 & Table 5 show that the group of YJG did not pass the pair samples t-test of increased Amc (p-value = 0.144) comparing to YSG (p-value = 0.0094 of highly significant increased Amc). Therefore the better Yoga experience of YSG performed a better meridian energy increase after yoga practice. Then we further check the p-values of each meridian in both groups. Table 4 shows the obvious evidence that not only the Amc but also all of the meridian currents in YSG showed the significant to very highly significant increase. Meanwhile Table 5 shows that the significant increase (p-value < 0.05) of meridian current was observed only in the hand meridians for YJG. Results of Table 4 inspire the overall enhancement of body health by increasing all of the meridians’ energy for persons having deeper experience in practicing yoga. It is interesting to study persons of lesser yoga experience (YJG) to show their beginning benefit to human’s tissues or organs that have possible relationship to the hand meridians from TCM theorem.

A. For yoga senior group (YSG)

B. For yoga junior group (YJG)

Figure 2 Average value of the meridian currents (Amc) calculated from 24 Ryodoraku acupoints before and after yoga practice (A & B).

Variables |

Before Yoga |

After Yoga |

p-value2 |

Amc1 |

32.8±12.3 |

47.0±9.0 |

0.0094** |

Hand meridians4 |

|||

Lung (LU9) |

42.1±16.5 |

61.9±20.3 |

0.00013*** |

Pericardium (PC7) |

36.6±12.5 |

53.3±8.8 |

0.00012*** |

Heart (HT7) |

36.6±15.8 |

50.6±14.0 |

0.0072** |

Small intestine (SI5) |

43.8±19.4 |

58.7±25.3 |

0.0283* |

Triple energizer (TE4) |

53.6±22.0 |

74.1±19.5 |

0.0060** |

Large intestine (LI5) |

45.4±18.4 |

63.5±25.9 |

0.0112* |

Foot meridians4 |

|||

Spleen (SP3) |

20.9±15.0 |

34.3±15.0 |

0.00039*** |

Liver (LR3) |

18.6±17.4 |

36.5±17.3 |

0.0137* |

Kidney (KI5) |

16.7±12.3 |

27.3±19.2 |

0.00080*** |

Bladder (BL65) |

23.5±15.4 |

32.3±13.2 |

0.0092** |

Gall Bladder (GB40) |

15.3±10.6 |

26.3±17.4 |

0.00034*** |

Stomach (ST42) |

30.2±18.1 |

44.7±15.3 |

0.00064*** |

Table 4 Measurement of meridian currents (μA) for yoga senior group (YSG)

*p < 0.05 (significant)

**p < 0.01 (highly significant)

***p < 0.001 (very highly significant)

1Amc is the average value of the meridian currents (24 Ryodoraku acupoints).

2p-value for pair t-test comparison of measurements at specific Ryodoraku acupoints before and after yoga practice

4Hand meridians include: LU, PC, HT, SI, TE, and LI; foot meridians include SP, LR, KI, BL, GB, and ST.9

Variables |

Before Yoga |

After Yoga |

p-value2 |

Amc1 |

46.6±19.5 |

58.3±22.1 |

0.144 |

Hand meridians4 |

|||

Lung (LU9) |

52.4±24.5 |

66.1±27.6 |

0.0189* |

Pericardium (PC7) |

43.7±16.1 |

56.3±22.2 |

0.0031** |

Heart (HT7) |

41.6±16.9 |

59.9±23.5 |

0.0032** |

Small intestine (SI5) |

60.1±23.9 |

81.0±29.5 |

0.0090** |

Triple energizer (TE4) |

74.5±24.4 |

88.3±26.6 |

0.0519 |

Large intestine (LI5) |

60.6±27.6 |

78.5±28.5 |

0.0114* |

Foot meridians4 |

|||

Spleen (SP3) |

34.8±20.4 |

38.7±17.9 |

0.611 |

Liver (LR3) |

41.1±22.0 |

49.8±23.0 |

0.104 |

Kidney (KI5) |

34.4±24.5 |

39.8±21.3 |

0.18 |

Bladder (BL65) |

34.9±17.4 |

44.7±23.3 |

0.13 |

Gall Bladder (GB40) |

35.7±19.8 |

41.5±18.0 |

0.123 |

Stomach (ST42) |

45.3±25.0 |

55.1±20.0 |

0.146 |

Table 5 Measurement of meridian currents (μA) for yoga junior group (YJG)

*p < 0.05 (significant)

**p < 0.01 (highly significant)

***p < 0.001 (very highly significant)

1Amc is the average value of the meridian currents (24 Ryodoraku acupoints).

2p-value for pair t-test comparison of measurements at specific Ryodoraku acupoints before and after yoga practice

4Hand meridians include: LU, PC, HT, SI, TE and LI; foot meridians include SP, LR, KI, BL, GB and ST9

The hand meridians include Lung (LU), Pericardium (PC), Heart (HT), Small Intestine (SI), Triple Energizer (TE) and Large Intestine (LI).9. From the ordinary yoga program, participants were instructed to maintain their concentration and synchronize their breaths with movements during the yoga session.5 From the benefit of LU meridian (Table 4 & Table 5), it could be related to the breathing practice in all of yoga lesson. According to the TCM theorem, the meridians HT and PC relate to the heart function and also blood governed by the heart, which flows all over the body, particularly that part of blood serving as the basis for the physiological activities of the heart, including mental activities reflecting its physiological and pathological conditions. For example, the syndrome of heart blood deficiency in TCM has been considered as a pathological change of the heart that causes dizziness, insomnia, dream-disturbed sleep, palpitation and thread weak pulse9,14 Meanwhile it has been reported that the efficacy of yoga in the primary and secondary prevention of ischaemic heart disease and post myocardial infarction patient rehabilitation.15It also has been studied that the yoga group had a significant increase in high-frequency HRV and decreases in low-frequency HRV after the intervention. The yoga group also reported significantly reduced depressive symptoms, anxiety and perceived stress.5 Yoga group as compared to control group was significant reduction in systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure and serum potassium.16

According to the TCM theorem, the meridian TE is a collective term for the three portions of the body cavity, through which the visceral energy (qi) is transformed. TE is said to occupy the thoracic and abdomino-pelvic cavities as the upper, middle and lower energizers, respectively. Meanwhile the upper, middle and lower energizers, could be viewed as the energizers for lung, heart or pericardium (upper), stomach or spleen (middle) and large intestine or bladder (lower), respectively.9,14 Traditionally, based on the meridian line of TE, the acupoints of TE could be used for relieving the disorders or pain of head, ears, eyes, throat, shoulder, elbow, arm and wrist as well as diseases involving the regions through which the meridian runs.9,14 Meanwhile yoga program reduces pain, anxiety and depression and improves spinal mobility in patients with chronic low back pain more effectively than physiotherapy exercises.17 According to the TCM theorem, the meridians SI and LI relate to the digestion and excretion functions of human body, respectively. It is well known that yoga practice influences functions such as digestion, heart rate and respiratory rate as a compulsory stabilizing response to stress and other environmental challenges.18 Yoga poses work on the soft tissues of the body. When the organs of the digestive system are compressed in poses, waste-bearing fluids in those areas are encouraged out of the tissues.19

We also find a very interesting phenomenon from data of YJG. According to the theorem of TCM, the properties of twelve meridians can be divided into six pairs of viscera vs. bowels that in the relationship of Yin vs. Yang meridians, such as LU vs. LI, SP vs. ST, HT vs. SI, KI vs. BL, PC vs. TE and LR vs. GB. Each of these pairs interacts with each other to affect the physiological activity of human body.9,14,20 The six pairs of meridians have been organized in Table 6 and also show their p-values (Table 5) of YJG. Table 6 shows the consistency of similar trace of p-values in each pair meridians; especially it shall be emphasized that the simultaneously significant effects of yoga practice on the increase of meridian currents in each pairs of LU vs. LI, HT vs. SI and PC vs. TE, meanwhile, simultaneously insignificant effects on each pairs of SP vs. ST, KI vs. BL and LR vs. GB. This result could be the statistical evidence-based data, stimulated by the yoga practice, but to show the possible connection to pair-meridians theorem from TCM. The concept of Yin-Yang interaction or balance, as proposed by the pair-meridians in Table 6, is an important theorem from TCM. The stimulation of pair-meridians simultaneously to reach Yin-Yang balance is considered the effectiveness judgment of any chemical or physical medicines from TCM.14 We also investigated other physical medicines on the stimulation of pair-meridians that will be reported in the near future. From the present and unpublished data, we find the yoga practice is an effective way to stimulate pair-meridians and reach Yin-Yang balance as measured by EMAS. To consider the human body balance, Jeter et al. reported that imbalance is often the result of multiple shared risk factors, such as psychosocial factors, self-reported health status and physical fitness. Yoga is a strong candidate for therapeutic intervention, since it provides a comprehensive, integrated approach that can address multiple risk factors at once.8 The practice of yoga unifies the mind and body through coordinated breathing, movement and meditation, which has been known to promote well-being and reduce stress, cardiovascular disease, mental health, chronic pain and sleep disorders.18

Ying (Viscera) Meridians |

Yang (Bowels) Meridians |

||||||

Name1 |

Meridian2 |

p-value3 |

Name1 |

Meridian2 |

p-value3 |

||

Greater yin (Taiyin) |

Hand |

LU |

0.0189* |

Yang brightness (Yangming) |

Hand |

LI |

0.0114* |

Foot |

SP |

0.611 |

Foot |

ST |

0.146 |

||

Lesser yin (Shaoyin) |

Hand |

HT |

0.0032** |

Greater yang (Taiyang) |

Hand |

SI |

0.0090** |

Foot |

KI |

0.18 |

Foot |

BL |

0.13 |

||

Reverting yin (Jueyin) |

Hand |

PC |

0.0031** |

Lesser yang (Shaoyang) |

Hand |

TE |

0.0519 |

Foot |

LR |

0.104 |

Foot |

GB |

0.123 |

||

Table 6 Six pairs of Yin vs Yang meridians and their p-values of yoga junior group (YJG)

1Name of three Ying and three Yang meridians9

2The divided pairs of Yin vs. Yang meridians are based on the theorem of Traditional Chinese Medicine; six pairs of meridian are LU vs. LI, SP vs. ST, HT vs. SI, KI vs. BL, PC vs. TE and LR vs. GB.14,20

3p-value from Table 5

This is the first study to find the possible connection of beneficial effect of yoga practice on the health of human body by the measurement of twelve meridians current (energy) enhancement quantified by EMAS device. We found that yoga participants with deeper experience (YSG of more than one year) showed their statistically significant increased Amc energy calculated from currents of 24 Ryodoraku acupoints, as well as the increased twelve meridian energies, separately measured by EMAS. Yoga participants with lesser experience (YJG of less than two months) could not show their statistically significant increased Amc. But YJG could showed their significantly increased energies of hand meridians, e.g. LU, PC, HT, SI and LI that in TCM theorem would relate to the well-known improving human functions of breathing, blood pressure control, better heart rate variability, anti-depression, good digestion and better excretion by yoga practice. In this study, we also exemplified the possible connection between the well-known improving human body balance function of yoga practice with the balanced energy improvement in pair meridians (e.g. LU vs. LI, HT vs. SI and PC vs. TE) from the Ying-Yang balance theorem of TCM.

The authors are grateful to Miss Feng-tzu Chiu of City Yoga (Taipei) for providing technical support.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

©2017 Hsu, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.