MOJ

eISSN: 2379-6162

Research Article Volume 6 Issue 6

Department of Surgery, Aligarh Muslim University, India

Correspondence: Maulana Mohammed Ansari, Ex-Professor of General Surgery, J N Medical College, B-27 Silver Oak Avenue, Street No. 4 End, Dhaurra Mafi, Aligarh, UP, India, Tel 0091-9557449212

Received: October 27, 2018 | Published: December 10, 2018

Citation: Ansari MM. Multiple arcuate lines: live surgical anatomy during laparoscopic total extraperitoneal preperitoneal (TEP) hernioplasty. MOJ Surg. 2018;6(6):190-196 DOI: 10.15406/mojs.2018.06.00151

Background Recent studies have revised the traditional concepts of rectus sheath formation and morphological variations of posterior rectus sheath. Studies on live surgical anatomy of arcuate line, a crucial surgical landmark during Laparoscopic total extraperitoneal preperitoneal (TEP/TEPP) hernioplasty is totally lacking in literature except for the recent report by the author Ansari MM. Existence and morphology of multiple arcuate lines observed during TEPP hernioplasty are highlighted herein with their significance.

Patients and methods TEPP hernioplasty was performed for uncomplicated primary inguinal hernia in adult patients through posterior rectus canal with 3 ports in midline and direct telescopic dissection under CO2 insufflation at 12mmHg. Instant documentation and video recording was done.

Results TEPP hernioplasty was successful in 68 hernias (Unilateral 52; Bilateral, 8) in 60 adult male patients. Three patients with early conversion were excluded. Mean age and BMI of patients were 50.1±17.2 years (range 18-80 years) and 22.6±2.0 kg/m2 (range 19.5-31.2 Kg/m2) respectively. Ten patients with unilateral hernias had secondary arcuate line (3 patients with incomplete posterior rectus sheath (PRS) with primary arcuate line; 7 patients with complete PRS with absent primary arcuate line). Six patients showed multiple arcuate lines (3 patients with incomplete PRS; 3 patients with complete PRS). Secondary arcuate lie in incomplete PRS was single in 2 patients and double in 1 patient, and the secondary arcuate line in complete PRS was double in 1 patient and triple in 2 patients. Moreover, 4 patients with complete PRS had single secondary arcuate line, and 44 patients with incomplete PRS had single primary arcuate line. Secondary arcuate line was well-defined in 7 patients and ill-defined in 3 patients. Presence of secondary arcuate line(s) compounded the already complex preperitoneal anatomy and also created anatomical confusion in the mind of unwary operator with increased technical challenge to perform laparoscopic TEPP hernioplasty.

Conclusions During the TEPP hernioplasty in adult patients, multiple arcuate lines were recorded in 6 out of 60 adult patients, namely, triple secondary arcuate line with absent primary arcuate line in 2 patients, double secondary arcuate line with absent primary arcuate line in 1 patient, double secondary arcuate line with single primary arcuate line in 1 patient, single secondary arcuate line with single primary arcuate line in 2 patients. Multiple arcuate lines increased anatomical complexity and confusion as well as increased surgical challenge to perform seamless TEPP hernioplasty with ease, rapidity and safety.

Keywords: total extraperitoneal preperitoneal hernioplasty, arcuate line, multiple arcuate lines, primary arcuate line, secondary arcuate line, henle’s ligament, primary arcuate line, posterior rectus sheath, unilateral hernias, aponeuroses, rectus sheath

ERSC, effective rectus sheath canal; TEP, total extraperitoneal preperitoneal; PRS, posterior rectus sheath; ASA, American society of anesthesiologists; PAC, pre-anaesthetic check-up; C-PRS, complete posterior rectus sheath; I-PRS, incomplete posterior rectus sheath; TEPP, laparoscopic total extraperitoneal preperitoneal

Recent gross anatomic studies have revised the traditional concepts of the rectus sheath and its component aponeuroses with frequent variations in the arcuate line formation.1,2 Studies on their live surgical anatomy is totally lacking in the literature except for the recent reports by the author.3–7 This paper highlights the surgical anatomy of the multiple arcuate lines for their existence and morphological variations studied during the laparoscopic total extraperitoneal preperitoneal (TEP/TEPP) hernioplasty as well as their significance to the surgical technique of TEPP hernioplasty.

A clinical prospective study was designed and prepared under the ethical approval by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Aligarh Muslim University, India in April, 2010 to January, 2011 for award of degree of PhD (Surgery) for anatomical observations during the surgical procedure of the laparoscopic total extraperitoneal preperitoneal (TEPP) hernioplasty. The TEPP hernioplasty was performed from February, 2011 to November, 2016 in adult patients with inguinal hernia at the J. N. Medical College Hospital, Aligarh Muslim University, India under the written informed consent.

Recruitment criteria included (1) Patient’s preference for laparoscopic repair of hernia, (2) Patient’s capacity to bear additional cost of laparoscopic surgery and larger mesh, (3) Fit for general anaesthesia as assessed through pre-anaesthetic check-up (PAC) clinic in outpatient department, and (4) Timely availability of the expertise (the author) and the functioning laparoscopic equipment/instruments. Inclusion criteria in the study consisted of (1) Age 18 years or above, (2) ASA Grade I & II of American Society of Anesthesiologists, (3) Uncomplicated fully reducible primary inguinal hernia, and (4) Successful completion of TEPP hernioplasty. Exclusion criteria of the study were (1) Age less than 18 year, (2) ASA Grade more than II, (3) Recurrent/Complicated inguinal hernia, (4) Femoral or other groin hernia, (5) History of lower abdominal surgery, and (6) Patient’s reluctance for the laparoscopic hernia repair. Patients’ demographics and anatomic observations were first recorded timely in a Specific Proforma and then detailed in Microsoft Excel spread sheet. Deurenberg’s formula was used to calculate the body mass index (BMI) of the patients.8 TEPP hernioplasty was performed through the posterior rectus sheath approach with the 3-midline-port technique with patient supine under general anaesthesia. The surgical technique was consistently same as reported earlier by the author.3–7,9–11

In the present study, the primary outcome measures consisted of the morphology of the anatomical structures observed during the laparoscopic TEPP hernioplasty, and details of the double/multiple arcuate line are presented herein. The definition of the primary and the secondary arcuate line adopted in the present study was same as originally described by Mackay12 and by Walmsley13. When the Arcuate line was formed by shifting of most of the aponeurotic fibres from the posterior to the anterior rectus sheath, it was labelled as the ‘typical’ arcuate line or ‘true fold’,13 in contrast to the secondary arcuate line and Henle’s Band formed in the complete often-attenuated posterior rectus sheath between the umbilicus and the pubic bone.12 Data analysis was done with help of Statistical Package for Social Sciences (v. 21 IBM SPSS Statistics 21.0, USA). All data were expressed as mean±sd (standard deviation) and a p-value of <0.05 was taken as statistically significant.

Sixty six adult patients with uncomplicated primary inguinal hernia were recruited for the study (Male, 63; Female, 3). The three female patients could not undergo laparoscopic TEPP hernioplasty due to the exclusion criteria (lower abdominal surgery, 2; associated femoral hernia, 1) and were excluded from the study. Three male patients were also excluded from the study due to early forced conversion to TAPP (n=1) and open surgery (n=2). Causes of conversion included (1) peritoneal injury just after insertion of the first optical port, (2) instrument injury to deep inferior epigastric vessels, and (3) hypercarbia with haemodynamic unstability. Therefore, TEPP hernioplasty was completed successfully in only 60 male patients who constituted the body of the present study. There were 52 unilateral hernias (left side 35; right side17) and 8 bilateral hernias, and hence, the data analysis was performed for 68 successful hernioplasties (Unilateral TEPP 58; Simultaneous Bilateral TEPP 5). Mean age of the patients was 50.1±17.2 years (range 18-80 years), and the mean BMI was 22.6±2.0 kg/m2 (range 19.5-31.2 Kg/m2). Ten out of the 60 patients were observed to have one/more in-transit secondary Arcuate line in their posterior rectus sheath as shown in Table 1 and Table 2. Arcuate line was recorded double/multiple in 6 out 10 patients either by a combination of the primary and secondary arcuate lines in patients with the incomplete posterior rectus sheath (n=3) or by a combination of only secondary arcuate lines in patients with complete posterior rectus sheath (n=3) (Table 1)(Table 2).

S. No. |

Age (Years) |

Sex |

BMI (Kg/m2) |

ASA Grade |

Occupation |

Diagnosis |

Operation Done |

Posterior Rectus Sheath (PRS) |

Primary Arcuate Line (PAL) |

Secondary Arcuate Line (SAL) |

Multiple Arcuate Lines |

1 |

50 |

M |

23.2 |

1 |

Field Work |

Rt. DIH |

Rt. TEPP |

IPT |

Well-Defined |

Single Well-defined |

Double |

2 |

40 |

M |

22.5 |

1 |

Labourer |

Rt. IIH |

Rt. TEPP |

IPT |

Well-Defined |

Single Ill-defined |

Double |

3 |

55 |

M |

22.1 |

2 |

Office Worker |

Lt. DIH |

Lt. TEPP |

IPT |

Well-Defined |

Double Well-defined |

Triple |

4 |

35 |

M |

23 |

1 |

Labourer |

B/L IIH |

Rt. TEPP |

CGA |

Absent |

Double Well-defined |

Double |

5 |

53 |

M |

21.5 |

2 |

Office Worker |

Rt. IIH |

Rt. TEPP |

CTO |

Absent |

Triple Well-defined |

Triple |

6 |

20 |

M |

23.2 |

1 |

Student |

Lt. IIH |

Lt. TEPP |

CTO |

Absent |

Triple Well-defined |

Triple |

7 |

58 |

M |

22.9 |

1 |

Field Work |

Rt. IIH |

Rt. TEPP |

CGA |

Absent |

Single Well-defined |

- |

8 |

64 |

M |

20.9 |

1 |

Field Work |

Rt. IIH |

Rt. TEPP |

CGA |

Absent |

Single Well-defined |

- |

9 |

40 |

M |

23.5 |

1 |

Labourer |

Rt. IIH |

Rt. TEPP |

CTO |

Absent |

Single Well-defined |

- |

10 |

51 |

M |

22.8 |

2 |

Office Worker |

Rt. IIH |

Rt. TEPP |

CWT |

Absent |

Single Ill-defined |

- |

Mean±SD |

46.6±12.9 |

|

22.6±0.8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 1 Demographic characteristic of 10 patients with secondary arcuate line who underwent laparoscopic TEPP hernioplasty

TEPP, total extraperitoneal preperitoneal (hernioplasty); M, male; BMI, body mass index; ASA, American society of anaesthesiologists; PRS, posterior rectus sheath; Rt., right; Lt., left; DIH, direct inguinal hernia; IIH, indirect inguinal hernia; IPT, partly tendinous incomplete PRS; CGA, grossly attenuated complete PRS; CTO, thinned-out membranous complete PRS; CWT, whole-tendinous complete PRS

S. No |

Posterior Sheath (PRS) Rectus |

Primary Arcuate Line (PAL) |

Secondary Arcuate Line (SAL) |

Hernias N |

% |

Patients N |

% |

1 |

Incomplete PRS |

Present |

Single SAL in IC-PRS |

2/54 |

3.7 |

2/47 |

4.3 |

(n=54) |

(n=54) |

Double SAL in IC-PRS |

1/54 |

1.9 |

1/47 |

2.1 |

|

2 |

Complete PRS |

Absent |

Single SAL in C-PRS |

4/14 |

28.6 |

4/13 |

30.8 |

(n=14) |

(n=14) |

Double SAL in C-PRS |

1/14 |

7.1 |

1/13 |

7.7 |

|

Triple SAL in C-PRS |

2/14 |

14.3 |

2/13 |

15.4 |

|||

|

Total |

|

|

10/64 |

14.7 |

10/60 |

16.7 |

Table 2 Distribution of secondary arcuate lines in 10 patients who underwent laparoscopic TEPP hernioplasty

TEPP, total extraperitoneal preperitoneal (hernioplasty)

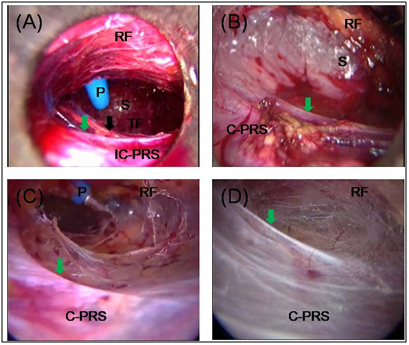

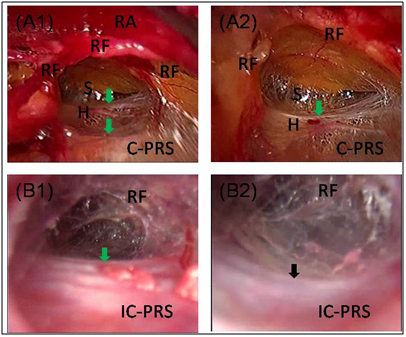

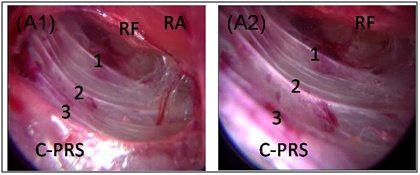

Secondary arcuate line was recorded in 7 out of 13 patients with complete posterior rectus sheath (C-PRS) with absent primary arcuate line; and the secondary arcuate line was also recorded in 3 out of 47 patients with incomplete posterior rectus sheath (I-PRS) with primary arcuate line as in Table 1 and Table 2. Secondary arcuate line was single in 6 out of 10 cases Figure 1, double in 2 cases Figure 2 and triple in 2 cases (Figure 3) (Table 2); and the secondary arcuate line was easily recognizable sharp well-defined in 7 out of 10 cases (Figure 1-3)(Table 3) and rather-difficult-to-recognize indistinct/ ill-defined in 3 out 10 cases (Figure 1) (Figure 3) (Table 3). Mean age of patients with secondary arcuate line was 46.6±12.9 years (range 20-64 years) (Table 1) and it was not different significantly from the mean age (50.8±17.9 years; range 18-80 years) of the patients without secondary arcuate line (CID, -16.140 to 7.740; t, 0.7041; df, 58; sig., 0.4842; p>0.05). Patients’ mean BMI was 22.56±0.8 kg/m2 (range 20.9-23.5 Kg/m2) Table 1 and it was not statistically different from the mean BMI (22.58±2.2 kg/m2; range 19.3-31.2 Kg/m2) of the patients without secondary arcuate line (CID, -1.4391 to 1.3991; t, 0.0282; df, 58; Sig., 0.9776; p >0.05).

Figure 1 Single secondary arcuate lines as viewed in posterior rectus canal of 4 patients: (A) single well-defined secondary arcuate line (green arrow) and well-defined primary arcuate line in incomplete posterior rectus sheath (IC-PRS); (B & D) single Ill-defined secondary arcuate line (green arrow) in membranous complete posterior rectus sheath (C-PRS); (C) single well-defined secondary arcuate line in partly-tendinous complete posterior rectus sheath; RF, rectusial fascia covering rectus abdominis muscle; S, sign of lighthouse; TF, transversalis fascia; Black Arrow, indicates well-defined primary arcuate line; P, blue plastic working port11

Figure 2 Double arcuate lines as viewed in posterior rectus canal of 2 patients: (A1 & A2) Double arcuate lines (green arrows) in grossly attenuated complete posterior rectus sheath (C-PRS); (B1 & B2) Secondary arcuate line (green arrow) and primary arcuate line (black arrow) in partly-tendinous incomplete posterior rectus sheath (IC-PRS); RF, rectusial fascia covering rectus abdominis muscle (RA); S, sign of lighthouse; H, Henle’s Band;11

Figure 3 Triple arcuate lines as viewed in posterior rectus canal of a patient: (A1 & A2) Triple arcuate lines (1, 2, 3) in partly tendinous complete posterior rectus sheath (C-PRS); RF, rectusial fascia covering rectus abdominis muscle (RA)11

S. No. |

PRS Type |

Primary Arcuate Line |

Secondary Arcuate Line |

|

|

||||||||

Morphology |

Hernias |

Patients |

Morphology |

Hernias |

Patients |

Total |

|||||||

|

|

|

N |

% |

N |

% |

|

N |

% |

N |

% |

|

|

1 |

Incomplete PRS |

Well-Defined |

40/54 |

74.1 |

34/47 |

72.3 |

Well-Defined |

2/54 |

3.7 |

2/47 |

4.3 |

3/47 |

6.4 |

Ill-Defined |

14/54 |

25.9 |

13/47 |

27.7 |

Ill-Defined |

1/54 |

1.9 |

1/47 |

2.1 |

||||

2 |

Complete PRS |

Absent |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Well-Defined |

5/14 |

35.7 |

5/13 |

38.5 |

7/13 |

53.8 |

Ill-Defined |

2/14 |

14.3 |

2/13 |

15.4 |

|||||||||

Total |

|

|

54/54 |

100 |

47/47 |

100 |

|

10/68 |

14.7 |

10/60 |

16.7 |

10/60 |

16.7 |

Table 3 Morphology of primary & secondary arcuate lines in 10 patients who underwent laparoscopic TEPP hernioplasty

TEPP, total extraperitoneal preperitoneal (hernioplasty); PRS, posterior rectus sheath

Since the secondary arcuate line in patients with either IC-PRS or C-PRS was found variable and hence unreliable criteria for entry into the preperitoneal space during TEPP hernioplasty through the posterior rectus sheath approach, as compared to the classical primary arcuate line which is situated at ⅓rd to ½ of the umbilico-pubic distance. Thus the level of entry into the preperitoneal space was found dependent on the length of the Effective Rectus sheath Canal (ERSC) as reported in detail earlier by the author Ansari.9 Therefore, in presence of longer ERSC secondary to rather long incomplete posterior rectus sheath with low primary arcuate line or complete posterior rectus sheath, the posterior rectus sheath was cut open at/just below the level of the middle working port that approximately corresponded to the midpoint of the umbilico-pubic distance in order to get an optimal ERSC and ample ergonomic working, irrespective of the position of the secondary arcuate line(s). The cut/rent in the posterior rectus sheath was made transversely so as to create a now lower border the posterior rectus sheath to mimic the classical arcuate line, and this new arcuate line was termed as the ‘artificial arcuate line’ by the author.14

Traditionally the rectus sheath, i.e., the tendinous covering of the rectus abdominis muscle is considered to be formed by the aponeuroses of the oblique (external and internal) and transversus muscles; the aponeurosis of the internal oblique splits into two laminae at the lateral margin of the rectus muscle in the upper half of the abdomen, one lamina passing posterior to the rectus muscle, to blend with aponeurosis of the transversus and the other lamina passing anterior to the rectus muscle, to blend with the aponeurosis of the external oblique. The two laminae join again at the medial border of the rectus, forming the Linea Alba.1 In the lower abdomen, the posterior rectus sheath is said to be always aponeurotic and incomplete with the formation of a well-defined, sharp, concave-downward Arcuate line (of Douglas) at its lower border, secondary to sudden shifting of the fibres of the posterior lamina from the posterior to the anterior rectus sheath.15–23 However, recent studies have demonstrated that the termination of the posterior rectus sheath is variable, often being gradual.2,24 Moreover, in addition to the bi-laminar nature of the internal oblique aponeurosis, the aponeuroses of transversus abdominis and external oblique are now proved to be bi-laminar as well,1,21,25–28 although first wished so way back by Walmsley13 in order to explain his own observation of the morphological variations in the rectus sheath formation, and each of the two walls (anterior and posterior) of the rectus sheath is tri-laminar.21 However, to the best our knowledge, there is no clinical study of the arcuate line and posterior rectus sheath during the laparoscopic surgery reported in the literature apart from the ones recently published by the author.3–7,10,11,14

In 2001, Spitz and Arregui29 rightly pointed out that “Much of the confusion regarding the preperitoneal fascia, the posterior rectus fascia, and the transversalis fascia may stem from the erroneous anatomical preoccupation that all fibres of the rectus sheath pass anterior to the rectus muscle below the arcuate line.” Present study also confirmed the observations of Spitz and Arregui29 that “however with the improved optics and magnification afforded by the laparoscope, we have seen, as mentioned earlier, that the posterior rectus sheath continues in a variably attenuated fashion below the arcuate line.” Similar findings were also recorded much earlier by Walmsley13 and Anson30. Gradual thinning of the posterior rectus sheath with absence of the arcuate was also reported by the author6 and other investigators including Cunningham.31 Mackay12 and Walmsley13 documented frequent presence of fibrous condensations in the attenuated complete posterior rectus sheath, forming the secondary arcuate line (Henle’s Band). Present study also regarded the occurrence of Henle’s Band. Serious concern was raised when the intra-operative difficulties and complications were faced by even the experienced surgeons during the laparoscopic hernia repair and the development of the post-operative sequelae, especially debilitating neuropathies, and unacceptably high failure rates in the early studies of laparoscopic hernioplasty, offsetting the obvious advantages and better outcome of the newer laparoscopic approach. Wide anatomic variations in the inguinal anatomy reported frequently in the past literature got attention of a number of recent investigators as the possible reason for the intra-operative difficulties and complications.21,23,28,32,33 In a classic publication, Anson30 documented 43 variations/ defects of the internal oblique and transversus abdominis in a study of 500 groin dissections. Identification of the anatomic variations is now regarded paramount for the success of the seamless laparoscopic hernioplasty with better outcomes.34,35

Presence of a secondary arcuate line reflects the proposition of the surgical anatomy that it is not the termination of the posterior rectus sheath which continues beyond the secondary arcuate line, and confirmed the opinion of many investigators including Moffat19, Rizk21, Spitz and Arregui29 that the arcuate line observed during the gross anatomy dissection is artificially created by inadvertently removing the lower attenuated part of the often complete posterior rectus sheath, considering it merely fascia transversalis. In the present study of the laparoscopic TEPP hernioplasty, creation of an artificial arcuate line was found a necessity to access the preperitoneal space underneath the posterior rectus sheath and the transversalis as was reported in detail earlier by the author.14 While working within the posterior rectus canal, the technique and level of entry into the preperitoneal space is always a matter of dilemma, differing markedly among the experts across the globe.3,9,36–39 The dilemma is in reality a reflection of the wide variations in the posterior rectus sheath and/or its Arcuate line.4,6 Longer ERSC (effective rectus sheath canal) is associated with limited space, poor endovision and severe ergonomic limitations secondary to the wide-fulcrum effect with markedly decreased ease of the procedure.9,36 On the other hand, too short ERSC due to high primary arcuate line is fraught with increased risk of peritoneal injury that may necessitate early conversion, although it does not interfere with exposure or port-placement.5,7,36

Surgical significance of the secondary arcuate line(s) with/without presence of the primary arcuate line has not yet been explored in any clinical studies reported in the literature. In the present study of the live surgical anatomy during the laparoscopic TEPP hernioplasty, secondary arcuate line(s) discovered during the procedure added more complexities to the already complex preperitoneal anatomy,40 and created momentary confusion in the mind of the operator as was also experienced by the author, increasing the technical challenge further in the already demanding nature of the laparoscopic TEPP hernioplasty.41 The novel concept of the ERSC (effective rectus sheath canal) propounded earlier by the author9 really helped him to develop the surgical technique and level of entry into the surgical preperitoneal space as reported elsewhere in detail recently by the author.42 In other words, presence of the multiple arcuate lines adds to the complexity of the preperitoneal anatomy of inguinal hernia and the increased challenge of the already demanding nature of the TEPP hernioplasty, warranting further refinement of the surgical technique.

In 1991, Spaw43 observed that the lack of precise knowledge of the preperitoneal anatomy is the most limiting factor for the sound laparoscopic hernia repair. In 1994, James Rosser44 declared categorically that surgeon must be equipped with the ‘crisp, precise anatomical knowledge’ and he also pointed out very rightly that “the textbook description does not provide an organized, common-sense-based map of the preperitoneal anatomy to help the surgeon to perform the laparoscopic hernia repair with ease and safety”. Therefore, anatomic research during the newer surgical approach of the laparoscopic TEPP hernioplasty will go a long way not only to refine the surgical technique based on the real-time anatomy but also to popularise the logical procedure of TEPP hernioplasty, and is strongly recommended as emphasized by Avisse.45

During the laparoscopic total extraperitoneal preperitoneal (TEPP) hernioplasty in adult patients, multiple arcuate lines were recorded in 10 out of 68 cases. Triple secondary arcuate line with absent primary arcuate line was present in 2 out of 68 cases; double secondary arcuate line with absent primary arcuate line in 1 case, single secondary arcuate line with absent primary arcuate line in 4 cases, double secondary arcuate line with single primary arcuate line in 1 case, single secondary arcuate line with single primary arcuate line in 2 cases, and single primary arcuate line with no secondary arcuate line in 51 out of 68 cases. Detection of secondary arcuate line(s) during the laparoscopic TEPP hernioplasty not only added more complexities to the already complex preperitoneal anatomy but also created momentary confusion in the mind of the operator, increasing the technical challenge further in the already demanding nature of the laparoscopic TEPP hernioplasty. Further clinical research on live surgical preperitoneal anatomy is strongly recommended to facilitate further refinement in the real-time-anatomy-based surgical technique for performing the seamless TEPP hernioplasty with ease, rapidity and safety.

All figures and content of this article are reproduced with permission from ‘Ansari MM. A Study of Laparoscopic Surgical Anatomy of Infraumbilical Posterior Rectus Sheath, Fascia Transversalis & Pre-Peritoneal Fat/Fascia during TEPP Mesh Hernioplasty For Inguinal Hernia., Doctoral Thesis for PhD (Surgery), Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, India, 2016.’

None.

©2018 Ansari. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.