MOJ

eISSN: 2379-6383

Case Report Volume 11 Issue 2

Long Island University, Grossmont-Cuyamaca Community College District, USA

Correspondence: Daryl Johnson, Long Island University, Grossmont-Cuyamaca Community College District, Public Safety, USA, Tel 619-549-9709

Received: May 19, 2022 | Published: June 27, 2022

Citation: Johnson D. Case analysis: New York City emergency planning falls short for disabled. MOJ Public Health. 2022;11(2):97-102. DOI: 10.15406/mojph.2022.11.00382

Introduction: Historically, emergency management planners have neglected to include critical stakeholders in the actual planning process, which has left thousands of vulnerable individuals who are sensory or mobility impaired open to injury and illness, during and after emergencies. Ultimately, this left gaps in both the planning and recovery phases of an emergency response for the most vulnerable. Having a clear and comprehensive understanding of the entire city, including the political landscape encompassing the citizens, the complex infrastructure, and available resources, will help inform the who, what, where, when and how to effectively develop an all-inclusive emergency plan. Over time, and as a result of many different types of disasters occurring (e.g., hurricanes, terrorist attacks, explosions), emergency managers remain challenged to continually improve upon their planning process, engaging agencies and organizations at all levels (i.e., local, state, national) to better prepare for future emergencies. One such challenge, a successful class action lawsuit brought by the Brooklyn Center for Independence of the Disabled (BCID), mandated that New York City address significant gaps in emergency planning specific to transportation, evacuation, sheltering, and unique communication needs that affect over 900,000 New Yorkers with functional disabilities.1

Methods: Extensive online search for documents, resources, court settlements, press releases all having to do with lack of emergency planning and services for disabled populations across the United States.

Discussion: The DOHMH has now implemented a Post Emergency Canvassing Operation (PECO) and could be a model for other cities and states, on how to rapidly canvass, determine needs and provide referral following an emergency for the unique needs of the vulnerable population to mitigate the risk of injury or disease. This adds yet another layer of resources and support to a population that has historically been left behind.

Keywords: DOHMH, PECO, vulnerable population, emergency planning, BCID vs City of New York

New Yorkers with disabilities continue to confront the reality of the increased risk of harm and death due to disasters because New York City has not adequately prepared in addressing their needs before, during and after emergencies.1 A class action lawsuit, Brooklyn Center for Independence of the Disabled (BCID), et al. v. Mayor Bloomberg, et al. filed in September 2011, shortly after Hurricane Irene, alleged that the City of New York’s emergency preparedness plans are non-compliant with Title II of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).1 Title II states that “a public entity (i.e., includes local governments) shall operate each service, program, or activity so that the service, program, or activity, when viewed in its entirety, is readily accessible to and usable by individuals with disabilities”.2 Furthermore, the lawsuit alleged that New York City does adequately address the needs of the approximately 900,000 people living in the city with disabilities (DRA, 2011).

Under Title II of the ADA, emergency programs, services, activities, and facilities must be accessible to people with disabilities.3 Literature indicates that older people are both more vulnerable due to health conditions, cognitive impairment, social isolation, etc. and yet, more psychologically resilient due to life experiences.4 The elderly, defined as 65 years and older, make up a disproportionately high number of deaths in disasters and have numerous overlapping concerns with other vulnerable populations.4 New In 2010, it was estimated that York City’s elderly population was approximately 931,650 (Table 1), which was 11.7% of the city’s total population (Table 2).5 As baby boomers are aging and retiring the number of elderly people will continue to rapidly increase making it much critical for the city develop and implement comprehensive plans and programs to support those most vulnerable during emergencies. Is the lawsuit a catalyst for the New York City DOHMH to change how it supports the vulnerable population after an emergency?

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

2010 |

2020 |

2030 |

|

NYC |

605,235 |

813,827 |

947,878 |

951,732 |

953,317 |

937,857 |

931,650 |

1,055,950 |

1,352,375 |

Bronx |

105,862 |

152,403 |

170,920 |

151,298 |

140,220 |

133,948 |

132,716 |

139,589 |

172,653 |

Brooklyn |

202,838 |

259,158 |

289,077 |

279,544 |

285,057 |

282,658 |

281,517 |

323,192 |

409,769 |

Manhattan |

171,323 |

207,700 |

214,973 |

204,437 |

197,384 |

186,776 |

203,101 |

234,478 |

294,919 |

Queens |

109,731 |

174,032 |

247,286 |

281,328 |

288,343 |

283,042 |

253,522 |

281,536 |

372,068 |

Staten Island |

15,481 |

20,534 |

25,622 |

35,125 |

42,313 |

51,433 |

60,794 |

77,155 |

102,966 |

Table 1 New York City Elderly Population by Borough, 1950-2030

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

2010 |

2020 |

2030 |

|

NYC |

7.70% |

10.50% |

12.00% |

13.50% |

13.00% |

11.70% |

11.10% |

12.10% |

14.80% |

Bronx |

7.3 |

10.7 |

11.6 |

12.9 |

11.6 |

10.1 |

9.5 |

9.8 |

11.8 |

Brooklyn |

7.4 |

9.9 |

11.1 |

12.5 |

12.4 |

11.5 |

11 |

12.3 |

15.1 |

Manhattan |

8.7 |

12.2 |

14 |

14.3 |

13.3 |

12.2 |

12.2 |

13.6 |

16.1 |

Queens |

7.1 |

9.6 |

12.4 |

14.9 |

14.8 |

12.7 |

11.1 |

11.7 |

14.5 |

Staten Island |

8.1 |

9.2 |

8.7 |

10 |

11.2 |

11.6 |

12.4 |

14.9 |

18.7 |

Table 2 Elderly Population as a Percent of Total Population by Borough, 1950-2030

NOTE: The data for both tables was taken from “New York City (NYC) Department of City Planning (DCP)” (2006). Retrieved from https://www1.nyc.gov/html/dcp/pdf/census/projections_report.pdf

Background

The planning and preparations for a city of New York’s size takes resources, lots of them, both human and material. In 1996, the Office of Emergency Management (OEM), now known as the New York City Emergency Management (NYC EM), was established to conduct citywide planning and preparing for emergencies such as coastal storms, earthquakes, extreme temperatures and winter storms. This occurs through educating the public about preparedness, coordinating response and recovery efforts, and the collecting and disseminating of emergency information. To accomplish this,6 “…maintains a disciplined unit of emergency management personnel, including responders, planners, watch commanders, and administrative and support staff, to identify and respond to various hazards” (About OEM, para 1). The DOHMH Office of Emergency Preparedness and Response (OEPR) acts as a liaison with NYCEM to enhance DOHMH and New York City’s ability to prevent, prepare for, respond to, and recover from health emergencies (M. Raphael, personal communication, March 18, 2015). The objective of this case analysis is to discover New York City’s significant gaps in emergency preparedness planning by failing to provide people with disabilities meaningful access to specific program services (i.e., evacuation plans, shelter system, canvassing, and communication).

A comprehensive online search was conducted in 2015 to find articles, court records, and other resources to assist with this case analysis. Sample search criteria used were terms such as “BCID v. New York, Bloomberg,” “communicating with vulnerable populations,” and “emergency planning for vulnerable populations.” Additionally, research was conducted to investigate other jurisdictions across the United States who have and are handling the same types of planning issues affecting individual with access and functional needs. For example, Westchester County, NY, recently came to an agreement with Move, Inc., Disability Rights Advocates which was negotiated without a lawsuit being filed. The agreement includes developing a comprehensive Emergency Management Plan aimed at addressing coordinating requests for temporary housing, coordinating transportation during disasters, developing accessible messaging for communication purposes during emergencies, and handling resource requests for those with disabilities.7 Similar lawsuits were filed by DRA in Los Angeles,8 and Washington DC,9 all dealing with the same types of factors (e.g., communication, transportation, sheltering, etc.). Emergency preparedness planning gaps were identified, focused on access and services for those with disabilities before, during and after a disaster, and addressed with settlements or agreements.

Physical vulnerability and social vulnerability

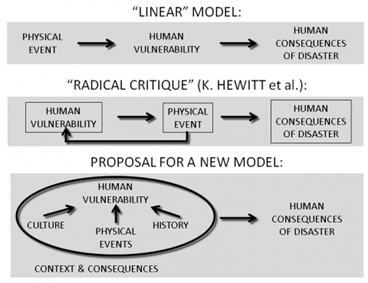

Vulnerable populations are rarely included in the emergency planning process, which leads to that population having the worst health outcomes during and after disasters.10 For the purposes of this case analysis, vulnerable populations include individuals who have serious hearing or vision difficulties and trouble walking or climbing stairs. There are a variety of terms used to identify those individuals who are at highest risk during and after an emergency. Common terms used include vulnerable populations, at-risk populations or the socially vulnerable.11 Vulnerability is a function of the exposure by explaining who or what is at risk and the degree to which people and places can be harmed.12 Theoretical models of vulnerability (Figure 1) generally are broken down by physical vulnerability and social vulnerability.13 Physical vulnerability relates to exposure (e.g., physical limitations, where you live, who you physically come into contact with). Social vulnerability is the individual and community characteristics influencing outcomes during and after an emergency. More specifically, the inability of an individual to perform the needed functions essential to maintain health in the event of an emergency.14 Encompassing both models, physical and social vulnerability, means the probability for loss (i.e., damage, injury) during and after an emergency.14 It is worth mentioning that despite the seemingly straightforward definition of vulnerability, the term’s meaning can vary dramatically depending on its context and who is using it.15 For example, Thywissen16 identifies 35 definitions for vulnerability while17 lists 18.

Figure 1 Possible evolution of models of disaster.

Retrieved from: https://journals.openedition.org/rccsar/docannexe/image/412/img-3.png

Triangulation of non-compliance

The class action lawsuit focuses on three areas where the city is in non-compliance with Title II: 1) not having accessible evacuation centers and general population shelters for the disabled; 2) not transporting and evacuating individuals with disabilities before, during and after an emergency; and 3) not communicating with individuals with disabilities before, during, and after an emergency (DRA, 2011).

Evacuation centers and shelters

A core responsibility of city government is to provide care and sheltering to those who become displaced during an emergency. Depending on the level of the disability a person has could determine whether they are able to stay with friends, family or neighbors during a disaster.1 For example, if an individual has mobility issues, friends, family and/or neighbors may not be physically able to assist either due to their own physical limitations or lack of building accommodations for disabled individuals. New York City has identified over 500 shelters throughout the city with most of them located within the New York City Department of Education (DOE) facilities. In theory, the city has the ability to shelter up to 600,000 people. However, when the City is considering which facilities to use as shelters during an emergency, there has not been a mandate in place to ensure that any of the buildings were accessible to people with disabilities.1 If a shelter happens to be set up for access by the disabled, shelter operators have not had a clear set of procedures indicating how to set up for, nor has it been required that any of the shelter areas actually are accessible (e.g. bathrooms, entrances, etc.).1

Transportation

At the time of the lawsuit, New York City had two evacuation plans in place: the Coastal Storm Evacuation Plan and the Area Evacuation Plan. The former is used when the City knows of an impending coastal storm or any other large-scale event that comes with advanced warning. The latter deals with general evacuation strategies that might occur without warning (i.e., terrorist attack) (R. Lynch, April 9, 2015). While the Coastal Storm Evacuation Plan does allow for coordination of evacuation assistance for homebound individuals who have no other options for evacuations, it fails to provide for any specific details on how the City will ensure that people with disabilities are able to evacuate. The Area Evacuation Plan does not include strategies or specifics regarding evacuating people with disabilities, and it provides little information about how such populations will be accommodated (R. Lynch, April 9, 2015). It does however include a Special Needs and Mass Care operational strategy but duplicates what is stated in the plan for coastal storms with regards to homebound individuals (I. Gonzalez, personal communication, March 24, 2015). Even in light of the fact that the City took great care to reduce the number of injuries and deaths sustained during Hurricane Sandy by shutting down all transportation (e.g., MTA, subway), they were negligent in ensuring that those who could not leave their homes on their own have an opportunity to do so and adequately provide transportation to those that needed it (M. Raphael, personal communication, March 18, 2015).

Communication

According to Paton et al (2001), the job of creating operational communication strategies (i.e., an individuals beliefs and their ability to act according to those beliefs) is potentially more complicated due to the diversity and distribution of vulnerable groups throughout a city. Developing adequate or effective strategies for notifying and communicating with such populations before or during emergencies is critical to ensuring their safety.1

Obligations to provide for vulnerable populations

More than two decades ago, Congress enacted the ADA to implement a broad mandate eliminating the discrimination against individuals with disabilities. That coupled with Title II states that a city’s obligation, at a minimum, must ensure that any individual deemed to have a disability have viable access to city services, help and events offered to the public.18 Another words, any such service, benefit or activity that is offered to the general public must also be available and accessible for an individual with a disability to receive or attend. If current policies and procedures do not exist to ensure or meet these criteria, then they should be modified.

Vulnerability landscape

There are three main needs addressed in the lawsuit: susceptibility, comprehensive emergency plan and addressing the needs of people with disabilities. For the city to understand how they must change current practices related to individuals with disabilities and emergencies, they must comprehend the current vulnerability landscape and how it historically has responded to this population during times of crisis.

New York City, the most densely populated in the United States, has more than 8.2 million people residing in an area of only 305 square miles. It is large, dense and has a complex infrastructure.19 Given the magnitude of this multifaceted city and system, the potential for significantly and negatively impacting people, places and systems, is greatly increased during an emergency making the city as whole more susceptible to damage and death (DRA, 2011). The events of September 11th, and the resulting deaths of those with mobility disabilities, essentially put the city on notice. They failed the disabled population both in preparedness and in their ability to recover from the events of that day.18 For example, individuals were trapped in the World Trade Center towers because they were unable to evacuate due to having no access to evacuation chairs or evacuation assistance. Furthermore, shelters that were in the frozen zones were not accessible affecting people with disabilities ability to carry out daily activities of life (e.g., dressing and eating). For those with vision impairments, they wandered about in confusion unable to decipher messages printed on signs or handouts. Those individuals needing supplies or medical equipment were left hanging with no access to transportation unlike their fully functional counterparts.18

Nine components of an effective emergency preparedness program

This case specifically addresses nine essential components that must be included in any emergency preparedness program: 1) the development of a comprehensive emergency plan; 2) the development of an assessment tool for the efficacy of those plans; 3) conducting an advanced needs assessment; 4) providing public notification and communication; 5) the development of procedures for sheltering in place; 6) provide shelter for those who need it; 7) provide evacuation and transportation assistance; 8) provide temporary housing for evacuees; and 9) the development of provisions for assisting in the recovery and remediation efforts post disaster.1 This list of necessary components would cover and assist not only the able-bodied residents but the disabled as well. The plaintiffs noted that while the city attempts to address each item, they have not done a thorough enough job to date.1

Addressing unique needs of persons with disabilities

The DOHMH recognizes the challenges in defining, identifying, and reaching vulnerable populations and acknowledges that these populations will often be defined by the nature and scope of the specific public health emergency. The DOHMH has developed a framework for identifying vulnerable populations determining vulnerability based on exposure, susceptibility, and functional abilities. The framework considers groups that are likely to be exposed or susceptible to a hazard. During a coastal storm, for instance, those living within a flood zone would be particularly at risk for exposure to damaging flood waters. Similarly, during an outbreak of pandemic flu, those who are obese, pregnant, or immune-compromised may be more susceptible to contracting the flu. Groups may also have limited functional abilities in which they are unable to perform particular tasks to maintain their health and cope during and after an emergency (I. Gonzalez, personal communication, March 24, 2015).

It is a core responsibility for the city to care for its vulnerable population. Therefore a more focused approach, with the development and implementation of a comprehensive plan, would help to ensure current gaps are filled leaving no individuals behind during an emergency. DOHMH has established relationships with partner organizations and strongly encourages them to reach out to their clients before, during and after emergencies. This network of partnerships needs to continue to be expanded with DOHMH supporting organizational efforts and assisting them with links to resources while providing clear and immediate actions that can be taken by communities, families and individuals.

Initial policy steps

One of the current challenges faced by the DOHMH is around policy. While it is the government’s responsibility to care for its citizens in response to an emergency, how long should such a response continue, (i.e., canvassing) who is responsible for it and when does it become enabling versus resilience building? Emergency planning and implementation in a city of New York’s size is a daunting undertaking. Given its complex make-up (i.e., multi-agency, egos, politics, etc.) it can be difficult to move agendas forward if all parties involved do not view the proposed change to be of benefit. (M. Raphael, personal communication, March 18, 2015). The fact is that before this lawsuit was finalized, the DOHMH was in the process of making plans to develop a canvassing operation. In speaking with one representative from the DOHMH, who wished to remain anonymous, he implied that he was satisfied with the outcome of the lawsuit. This was due to the fact that the city was obligated and mandated to make the required changes ultimately resulting in more resources, both human and material, to develop the comprehensive canvassing plan.

How hurricane sandy changed the landscape

Hurricane Sandy hit the city on October 29, 2012, causing massive amounts of water, electrical and structural damage in the city’s most vulnerable areas (i.e., subway, tunnels, buildings lining the waterfront, etc.). As a result of the storm, thousands of people were negatively affected with issues related to displacement, flooding and no heat (M. Stripling, personal communication, April 1, 2015). Given the impact of the storm it became alarmingly clear that door-to-door canvassing, citywide, needed to happen and happen quickly. The question became which agency would lead and coordinate this massive undertaking? DOHMH stepped up and led the efforts, which went on for weeks, going door-to-door checking on the status of people and their immediate needs (e.g., food, water, medical services, etc.). This would be the event that really validated and ignited the need and value for a canvassing operation to be developed and implemented (M. Stripling, personal communication, April 1, 2015).

After a disaster, the greatest risk of injury and death may be to those who were at-risk before the disaster (e.g., those with chronic medical conditions). Some people will have organizations that were providing essential medical or social services but many may not. New York City should coordinate outreach to these populations after a disaster (I. Gonzalez, personal communication, March 24, 2015). Currently, there is an Advanced Warning System (AWS) that exists where organizations sign up and receive alert messages about potential or existing emergencies (e.g., extreme heat conditions, cold weather, etc.). In 2015, there were many issues with that system. It had a limited reach since there was no current mandate that all organizations that are service providers sign up for it. Additionally, there was no tracking system in place to ensure those that were sent a message actually passed it onto their clients or if their clients actually got the message (T. Hadi, personal communications, April 2, 2015). Often there is a divide between government and community organizations. In order to reduce confusion and discontent, we need to do better at clearly outlining the roles and responsibilities of our partners and of our agencies. Ultimately, this will lead to better coordination of services which will lead to a strengthened response rather than a diminished one (I. Gonzalez, personal communication, March 24, 2015).

More than a decade after 9/11, there were no significant improvements with New York’s emergency preparedness and response program putting the cities disabled population continually in jeopardy of substantial harm and death during disasters. Hurricane Irene make this evident, and Hurricane Sandy soon demonstrated,20 once again why the lawsuit was filed. An outcome from that settlement was the development and implementation of a comprehensive canvassing program led by the DOHMH called the Post Emergency Canvassing Operation (PECO) which is a citywide door-to-door knocking program staffed by DOHMH staff and volunteers to rapidly identify populations post disaster and determine if they need services and connect them with those services. As stated earlier, while the need to develop this was known some time ago and initial planning was underway, the necessary human and material resources like money and equipment were not available. With this lawsuit came resources in large quantities. It is worth noting that this case was not filed for monetary reasons but to save the lives of the city’s most vulnerable. It was estimated the cost to fully develop PECO was about $4 billion or more. There are approximately 30,000 staff, from all over the city, assigned to PECO in the event of activation. The city was mandated to have PECO completely up and running by 2017 (R. Rotanz, personal communication, March 19, 2015).

At least one critical city service, building 60 accessible emergency shelters for people with disabilities, was late by two years. By September 2017, only 49 were completed.

Source:

The City. City Nearly Two Years Late on Making 60 Evacuation Shelters Accessible. 2019

https://www.thecity.nyc/2019/7/30/21210904/city-nearly-two-years-late-on-making-60-evacuation-shelters-accessible.

There are various models around the country currently using PECO-based canvassing. Here are a few:

NYC City Council Bill Int. No. 1065-A was signed into law on August 12, 2013 and states, in part, that NYC shall develop “a Door-to-Door Task Force that will be responsible for developing and implementing a strategy to locate and assist vulnerable and homebound populations, provide such individuals with information, and maintain a list of such individuals to assist with any recovery efforts that take place after such conditions and incidents, including the delivery of necessary supplies and services” ????. While canvassing of populations made vulnerable after a disaster is a key jurisdictional function there is no national ownership model. Furthermore, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Public Health Emergency Preparedness grant required that response strategies addressing the accessibility and functional needs of at-risk individuals be developed.23 Based on the unclear National Standard for canvassing, and political difficulty of assigning this to another...to another agency, and the health department’s comparatively robust emergency management program simultaneously, it was recommended that the DOHMH continue to manage door knocking to the vulnerable populations (M. Stripling, personal communication, April 1, 2015).

Having read and researched the city’s recent history and its lack of coordinating efforts specific to the vulnerable population, there are a variety of recommendations based on the canvassing plans moving forward. They are as follows:

The author declares there is no conflict of interest.

©2022 Johnson. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.