MOJ

eISSN: 2379-6383

Research Article Volume 12 Issue 1

1Health Systems Consult Limited (HSCL), No. 856 Olu-Awotesu Street, Jabi, 900101, Abuja, Federal Capital Territory, Nigeria

2Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, No. 43 Agadez Cres, Wuse 2, 904101, Abuja, Federal Capital Territory, Nigeria

3Head of Operations, Lagos State Health Management Agency (LASHMA), No. 17 Kafi Street, Alausa Ikeja, 101233, Lagos State, Nigeria

Correspondence: Maxwell Obubu, Health Systems Consult Limited (HSCL), No. 856 Olu-Awotesu Street, Jabi, 900101, Abuja, Federal Capital Territory, Nigeria, Tel +2348031951850

Received: October 27, 2022 | Published: March 22, 2023

Citation: Obubu M, Chuku N, Ananaba A, et al. Bed space, referral capacity and emergency response of the healthcare facilities in lagos state: a key to improving healthcare. MOJ Public Health. 2023;12(1):67-72. DOI: 10.15406/mojph.2023.12.00412

Background: A health system comprises various elements such as infrastructure, human resources, data systems, and financial systems. Adequate infrastructure, including buildings, equipment, supplies, and communication, is crucial to health services. In Nigeria, some healthcare facilities do not have the needed human and infrastructure resources to manage specific conditions, causing multiple referrals and endangering patients' lives. The present study assessed the availability of in-patient beds and the referral capacity and emergency response of the healthcare facilities in Lagos State.

Methods: This study leveraged Noi Polls census data on Health Facility Assessment for Lagos state conducted between November 2020 and December 2021. The survey was conducted in 1256 health facilities which are 53.8% of the entire health facilities in Lagos State, and 53.8% of the population of Lagos State was used to compute the bed/population ratio. A descriptive analysis was done to present the findings.

Result: Findings revealed that Lagos State has eight (8) beds per 10,000 population which is below the global average of twenty-six (26) beds per 10,000 population and the recommended five (5) beds per 1,000 population by the World Health Organisation. The results further reveal that healthcare facilities in Lagos State need additional 2,861 beds to reach the Sub-Saharan average in-patient beds of twelve (12) per 10,000 population and an additional 31,953 beds to reach the recommended five (5) per 1,000 populations by the World Health Organization.

Conclusion: Infrastructures such as beds, emergency rooms, and the emergency transportation services needed to transport patients to other facilities are lacking in most of the healthcare facilities in Lagos State. Secondary healthcare facilities in the State cannot discharge their roles, especially handling referred patients, as they lack bed space to care for in-patients and emergency rooms to carter for emergency cases.

Keywords: health infrastructural assessment, healthcare facilities. Lagos State, bed space, referral and emergency response, emergency rooms

The World Health Organization (WHO) Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research defines six building blocks of healthcare systems, the infrastructure constituting one component of the building block "service delivery".1 Adequate infrastructure, which includes buildings, equipment, supplies, and communication equipment, is crucial for health services.2,3 Poor service quality typically results from poor infrastructure, which wastes resources and threatens the health and welfare of patients and the general public.4,5 Skilled and motivated staff are essential for preventive and curative medical services, and drugs and vaccines are essential for maintaining people's health. However, the role of healthcare facility infrastructure as a major component of a healthcare system must not be underestimated. The term 'infrastructure' is used in manifold ways to describe the structural elements of systems.3 Defined infrastructure as the underlying foundation that supports a larger structure, the intrinsic framework of a system or organization, and the 'substructure' that underpins the 'superstructure.' It determines the system's capacity and capability to carry out its core functions and delivers on its core mandates and the corresponding quality of care and accessibility to health care delivery in society. In the context of a healthcare system and healthcare facilities, it can be seen as a major component of the structural quality of a health care system.6,7 The same applies to healthcare facilities, i.e., functionality, quality, and extent of such components and assets determine the accessibility, availability, quality, and acceptability of healthcare services as well as the working conditions of facility staff.8–13 Health infrastructure is understood in qualitative and quantitative terms to mean the quality of care and accessibility to health care delivery within a country.14 However, the authors of this article have defined "healthcare facility infrastructure" as the total of all physical, technical, and organizational components or assets that are prerequisites for delivering healthcare services.

To ensure quality service delivery, the World Health Organization (WHO) has recommended that health care infrastructure be 'formal and enduring,' requiring a strategic focus that is maintained over time on a sustainable basis.15 Formal and enduring infrastructure expects that their sustenance and maintenance should be endorsed as the statutory and systematic responsibility of government; rather than ad hoc or disjointed.3 The policy brief by Omuta, et al.,3 considers four (4) physical amenities, namely: sources of water supply, sources of electricity, number of available hospital beds, and type of communication facilities. Infrastructure must integrate the hospital, as the centre for acute and in-patient care, into the broader health care system and should facilitate the seven domains of quality: patient experience, effectiveness, efficiency, timeliness, safety, equity, and sustainability.3 Many amenities are required for optimal performance in the healthcare system, but this study is concerned with bed space, referral, and emergency response services of healthcare facilities in Lagos State.

According to the World Health Organization,16 a hospital bed is a bed that is regularly maintained, staffed, and used to accommodate and provide full-time care for a succession of in-patients. It must also be located in a ward or other area of the hospital where in-patients receive ongoing medical attention. The aggregated total constitutes the normally available bed complement of the hospital. In-patient hospital care beds accommodate patients formally admitted (or 'hospitalized') to a hospital for treatment and care and who stay for a minimum of one night. Beds in hospitals available for same-day or day-care patient care are usually not included in figures for total in-patient care beds—the WHO recommends five (5) beds for every one thousand (1000) population.16 In India, the bed: population ratio is 0.9 beds per 1000 population,17 while in Nigeria, it is 5 beds per 10,000 population,18,19 which is far below the global average of 2.9 beds per 1000 population.17 With an estimated 5 beds per 10,000 population, Nigeria will need an additional 117,000 beds costing approximately $12 billion, to reach the Sub-Saharan African average of 12 beds per 10,000 and an additional 350,000 beds costing approximately $37 billion to reach the global average of 26 beds per 10,000.18 This shortage of hospital beds in Nigeria could lead to an increased rate of mortality since patients are liable to be discharged prematurely.19

Bed management is the assignment and provision of beds, especially in a hospital where beds in specialist wards are scarce resources.20,21 Prompt distribution of beds to hospital patients can transform a stressful experience into a comforting and positive experience that will improve patients' well-being. The bed management role is in the vanguard of effectively utilizing vital but constrained hospital resources.22 Effective Bed management is critical to enabling the successful movement of patients through a hospital. It involves the medical care, physical resources, and internal systems needed to get patients from admission to is charge while maintaining quality and patient and provider satisfaction.23 Managing beds might seem simple, but bed management involves continuously monitoring hospital admissions, discharges, and hospital utilization indices to identify vacant beds across wards.17 Health facilities and the services they provide to the population must be managed based on available beds.21 The population's healthcare is impacted by the overcrowding of emergency services and the lack of available beds.24 In the continuum of medical care, hospital emergency departments continue to hold a highly strategic position in every society.25 Emergency rooms, which are open twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, are an essential part of healthcare, especially for those who need immediate attention.25 The emergency department (ED) is one of the few institutions that is always accessible and ready to help anyone; its services are offered without regard to one's social or economic standing and without an appointment.26 Overcrowding in accident and emergency departments (AEDs) has been a severe health issue for more than ten years.26 The inability of Nigeria's emergency departments to meet current demands is growing among the public and healthcare professionals.26 Makama, et al.,26 noted that AED use has increased, it should be noted that many communities now have more AE cases than they can handle. The resultant phenomenon, known as AED overcrowding, now poses a threat to those who are most in need of emergency services being able to access them.

WHO,27 developed a hospital emergency response checklist to assist hospital administrators and emergency managers in responding effectively to the most likely disaster scenarios. This checklist has nine components: command and control, communication, safety and security, triage, surge capacity, continuity of essential services, human resources, logistic and supply management, and post-disaster recovery. Each of the components has a list of priority actions to help hospital managers and emergency planners achieve the following goals: (1) continuity of essential hospital services; (2) well-coordinated implementation of hospital operations at every level; (3) clear and accurate internal and external communication; (4) quick adaptation to increased demands; (5) the effective use of scarce resources; and (6) a safe and conducive environment for healthcare workers. The growing concerns arising from the poor emergency response in Nigerian hospitals prove that the country's healthcare system is operating at a capacity far below what is expected of a healthcare system.26 The hospital system's incapacity raises severe public health concerns in responding to emergencies. The biggest obstacle to hospitals' emergency intervention is the lack of pre-emergency, emergency preparedness plans and coordination of the hospitals' response mechanisms.28 Some hospital emergency cases happen to be referrals from other health facilities lacking the capacity to handle such cases. The national health system provides three tiers of healthcare; primary, secondary, and tertiary.29,5 The three should benefit from client patronage, and their primary connection is a strong referral network. In Nigeria, many secondary and tertiary health facilities are crowded with patients with minor illnesses that can be treated at primary health centers. Many of these facilities' staff members are doing nothing.29 Patients are to make their initial contact at the primary health centers and thereafter, referred to higher tiers of medical care. A referral is a process in which a health worker at a level of the health system (initiating facility) seeks the assistance of a better or differently resourced facility at the same or higher level (receiving facility) to assist in, or take over, the management of the client's case".30,31 Sometimes, a patient might require multiple referrals before reaching an adequately resourced health facility. Some healthcare facilities do not have the human and infrastructure resources to manage specific conditions, causing multiple referrals. This, coupled with traffic and poor road conditions, could lead to delays in getting appropriate and timely care, putting a patient's life in danger in an emergency. This study addresses the reality of the health policies of large organizations such as the WHO and appropriately addresses details such as infrastructure and resolution capacity. Therefore, there is a need for more outstanding infrastructure to have a greater resolution capacity in emergencies. This study, therefore, assesses the bed space and the referral and emergency response services of the healthcare facilities in Lagos State.

The study leveraged primary data collected on health facilities assessment in Lagos state by Noi Polls between November 2020 and December 2021.32 The COVID-19 pandemic situation that existed in Lagos State at the time of the assessment influenced the technical approach used to evaluate the health facilities in the State. A telephone interview method was adopted for data collection, which decreased the risk of contracting and spreading the coronavirus. NOI Polls adopted a quantitative research methodology for the health facility assessment. At the same time, HSCL developed a list of health facilities using information from the State Ministry of Health (SMOH). The list served as a sample frame for health facilities in Lagos state. The sampling frame consisted of 2,398 health facilities, and a census approach was adopted. The data collection method used was Computer Assisted Telephone Interview (CATI). Health facilities' target respondents (chief medical directors, medical directors, and facility administrators) were interviewed over the telephone using a Questionnaire Processing Software for Market Research (QPSMR). The telephone interview call protocol specifies that each health facility in the sample frame is attempted six times for an interview before the health facility falls into the category of an unsuccessful call. Noi Polls engaged vital stakeholders to refine the technical assistance plan for the health facility assessment. These stakeholders included the State Ministry of Health (SMOH), Lagos State Health Management Agency (LASHMA), the Health Facility Monitoring and Accreditation Agency (HEFAMAA), Association of General and Private Medical Practitioners of Nigeria (AGPMPN), and other relevant professional bodies. The final health facility assessment dataset contains information on Facility Ownership, Facility level of Care, Accrediting body, Human Resources for Health, Basic Medical & Infection Prevention Equipment, Infrastructure, Available Services, Health Insurance Coverage, Medicines & Commodities, Financial Management Systems, Clinical Governance, and Covid-19 Response.

Lagos is one of the 36 states in Nigeria with an estimated population of 14,368,000 for the year 2020,33 only second to Kano States and with a population of 2,500/km2 and a human development index of 0.673.33 Lagos State has a total hospital/clinic population of 2,333; 458 public and 1875 private, of which 1574 are primary health facilities, 756 are secondary, and three are tertiary. Of this number, public/primary is 412, private/primary is 1162, public/secondary is 44, private/secondary is 712, public/tertiary is two, and private/tertiary is one (Federal Ministry of Health, 2021). The estimated population of Local Government Areas in Lagos State for 2020 used in the study was computed using a constant national growth rate of 3.3%34 and the geometric growth projection method adopted by City Population.34 The survey was conducted in 1256 health facilities which are 53.8% of the entire health facilities in Lagos State, and 53.8% of the population of Lagos State was used to compute the bed/population ratio.

The result in Table 1 shows that of the 1256 facilities considered for this study, 73.7% have overnight/in-patient and observation beds for adults and children, while 23.6% do not. The result further shows that 71.6% and 80.8% of facilities situated in urban and rural areas of the State have in-patient beds. Considering that only 22.9% of the facilities in this study situated in rural Lagos State, we cannot out rightly conclude that facilities in the rural areas of the State have more beds than those in urban. Ordinarily, one would expect the 1.7% of facilities owned by NGO's/Faith-Based organizations to have 100% in-patient and observation beds (Figure 1). However, this is not the case, as the study reveals that only 76.2% of these facilities have in-patient and observation beds compared to 74.2% of government/public and 73.6% of private-for-profit noting that the total percentage of healthcare facilities owned by government/public and private-for-public is 15%, and 82.9% respectively. Thus, the result reveals that private-for-profit healthcare facilities have more in-patient beds for adults and children. Surprisingly, 60.5% of the secondary healthcare facilities in Lagos State do not have in-patient beds.

Facility Ownership Type |

Facility's Level of Care |

Facility's Locality |

||||||

Total |

Government/ Public |

Private-For-Profit |

Others (NGOs, Mission/Faith-Based) |

SHC Facility |

PHC Facility |

Urban |

Rural |

|

Beds |

73.7 |

74.2 |

73.6 |

76.2 |

39.5 |

85 |

71.6 |

80.8 |

No Beds |

23.6 |

28.4 |

26.4 |

23.8 |

60.5 |

15 |

28.4 |

19.2 |

Table 1 Percentage of Facilities with overnight/in-patient and observation beds for both adults and children (excluding delivery beds/couches)

Figure 1 Percentage Distribution of Health Facilities Assessed by 'Locality' and 'Facility Ownership Type'.

By comparing the population of each local government to the bed available in the healthcare facilities, Ibeju/Lekki local government has the highest number of seventeen (17) beds per ten thousand (10,000) populations. Ikeja, Eti-Osa, and Surulere follow this with fourteen (14) beds per ten thousand (10,000) populations. In the third position, with eleven (11) beds per ten thousand (10,000) populations, are Alimosho, Ifako-Ijaye, and Ikorodu. Local government areas with the least average number of beds per ten thousand populations are Agege and Epe having three (3) beds. The result in Table 2 further shows that the number of beds per ten thousand (10,000) populations for Lagos State is eight (8), and this is far below the WHO recommendation of five (5) beds for every one thousand (1000) population.

LGA |

Population |

Number of beds |

Beds/10,000 Population |

Agege |

394300 |

127 |

3 |

Ajeromi-Ifelodun |

586925 |

414 |

7 |

Alimosho |

1126832 |

1205 |

11 |

Amuwo-Odofin |

280924 |

244 |

9 |

Badagry |

203007 |

194 |

10 |

Ifako-Ijaye |

365261 |

417 |

11 |

Ikeja |

271222 |

376 |

14 |

Mushin |

539567 |

189 |

4 |

Ojo |

520196 |

356 |

7 |

Oshodi-Isolo |

537179 |

404 |

8 |

Apapa |

190416 |

88 |

5 |

Eti-Osa |

242340 |

332 |

14 |

Lagos Island |

181633 |

81 |

4 |

Lagos Mainland |

278982 |

118 |

4 |

Surulere |

429415 |

611 |

14 |

Epe |

155189 |

49 |

3 |

Ibeju/Lekki |

100588 |

167 |

17 |

Ikorodu |

450808 |

508 |

11 |

Kosofe |

583045 |

440 |

8 |

Shomolu |

344623 |

201 |

6 |

Total |

7,782,452 |

6521 |

8 |

Table 2 Number of Beds per 10,000 populations in Lagos State

We examined Lagos State healthcare facilities with emergency rooms, and the result shows that 51% (641 health facilities) of the studied facilities have emergency rooms while 49% (615 health facilities) do not (Table 3). The result shows that 60.8% and 47.1% of government/public and private-for-profit health facilities do not have emergency rooms. Also, 73.8% and 40.9% of secondary and primary healthcare facilities in the State do not have emergency rooms. These statistics are no different when observed from the standpoint of the facility's locality.

Facility Ownership Type |

Facility's Level of Care |

Facility's Locality |

||||||

Total |

Government/ Public |

Private-For-Profit |

Others (NGOs, Mission/Faith-Based) |

SHC Facility |

PHC Facility |

Urban |

Rural |

|

Emergency Room |

51 |

39.2 |

52.9 |

61.9 |

26.2 |

59.1 |

51.5 |

49.1 |

No Emergency Room |

49 |

60.8 |

47.1 |

38.1 |

73.8 |

40.9 |

48.5 |

50.9 |

Table 3 Percentage of Facilities with emergency rooms

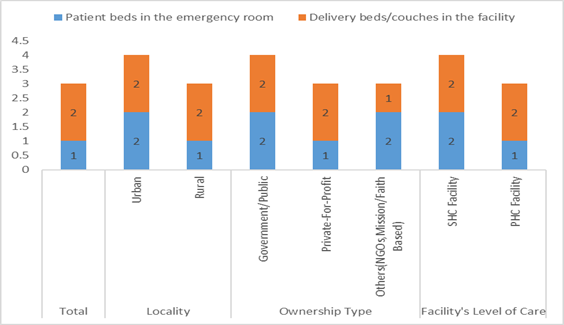

We examine the average number of patient beds in the emergency room and delivery beds/couches. The result in Figure 2 shows that, on average, there are two delivery beds/couches in the facilities and one patient bed in the emergency room. The same is obtainable in rural healthcare facilities, private-for-profit facilities, and primary healthcare facilities in the State. In contrast, the reverse is obtained in mission/faith-based facilities with one delivery bed/Couche in the facilities and two patient beds in the emergency room. Secondary healthcare facilities, government-owned facilities, and those in the urban areas have two beds on average in the emergency rooms and two delivery beds/couches in each facility.

Figure 2 Average number of patient beds in the emergency room and delivery beds/couches in the facilities.

Table 4 shows that 67.2% of the facilities with emergency rooms offer referral and emergency response services. 70.4% and 63.6% of the facilities in the rural and urban areas offer referral and emergency response services. We cannot say that facilities in the State's rural areas are doing better, considering the number of rural facilities considered for this study. 76.6% of the studied primary healthcare facilities offer referral and emergency response services compared to 38.8% of the secondary facilities. Secondary healthcare facilities having a Service Level Agreement (SLA) with other health facilities for managing trauma or emergency cases beyond the scope of service rendered are 38.8%, while primary is 61.9%. More secondary facilities (83.5%) than primary (63.4%) receive referred patients from other facilities, while 59.9% and 70.9% of the facilities in the rural and urban areas, respectively, receive referred patients from other facilities.

Total |

Locality |

Facility Ownership Type |

Facility's Level of Care |

|||||

Urban |

Rural |

Government/ Public |

Private-For-Profit |

Others (NGOs, |

SHC Facility |

PHC Facility |

||

Offering emergency services |

67.2 |

66.3 |

70.4 |

59.3 |

68.6 |

71.4 |

38.5 |

76.6 |

Having a Service Level Agreement (SLA) |

56.3 |

53.5 |

56.3 |

86.6 |

50.4 |

66.7 |

38.8 |

61.9 |

Having an emergency transportation service |

30 |

30.5 |

28.2 |

28.9 |

30 |

42.9 |

17.5 |

34.1 |

Refer patients out to other facilities |

94.3 |

93.9 |

95.8 |

97.4 |

93.8 |

95.2 |

85.1 |

97.4 |

Receives referred patients from other facilities |

68.4 |

70.9 |

59.9 |

43.3 |

73 |

71.4 |

83.5 |

63.4 |

Table 4 Percentage of facilities with referral and emergency response services

The average number of beds in the healthcare facilities in Lagos State is eight (8) per 10,000, which is more than the five (5) reported by Pharm Access Foundation,18 and Adeniyan,19 in Nigeria. This is, however, far less than the global average of twenty-six (26) beds per 10,000 population and the recommended five (5) beds per 1,000 populations by the World Health Organisation.17 Based on the findings of the present study, the healthcare facilities in Lagos State need additional 31,953 beds to reach the recommended five (5) per 1,000 populations by the World Health Organisation.17 Findings reveal that Agege and Epe local government areas (LGAs) have an average of three (3) beds per 10,000 population, while Mushin, Island, and Mainland have four (4) beds per 10,000 population each, which is far less than the state average of eight. Other local government areas on the left hand of the State's average of eight are Ajeromi-Ifelodun, Ojo, Apapa, and Shomolu.

Findings reveal that 26.3% of the studied facilities are without overnight/in-patient and observation beds for adults and children (excluding delivery beds/couches). These facilities cannot manage patients whom doctors and nurses must examine closely. This complete lack of hospital beds in some facilities could lead to the early discharge of patients since there is no place to keep and manage them; this could increase the mortality rate.14 The secondary healthcare facilities meant to receive referred patients from primary healthcare facilities.29 Lack beds, as 60.5% do not have overnight/in-patient and observation beds for adults and children. 85% of primary and 39.5% of secondary healthcare facilities studied have in-patient beds, suggesting that primary healthcare facilities are better equipped than secondary ones.

In contrast with health facilities with a wide emergency capacity, managing emergency cases in a healthcare facility without emergency rooms could be challenging. Findings reveal that 49% of the healthcare facilities studied may not effectively manage emergency cases since they operate without emergency rooms. This absence of emergency rooms is more pronounced in the second tier of healthcare, as 73.8% of them do not have emergency rooms when they should receive referrals from the first tier.5 60.8% of the government-owned facilities are also without emergency rooms, while 50.9% of the rural facilities have their share of the dearth of emergency rooms. These worrying statistics show that those facilities do not have emergency preparedness plans to respond to emergency cases.28 Emergency cases cannot be referred to such facilities because they cannot manage such.35 Though the statistics show that a higher percentage of healthcare facilities in the rural areas (70.4%) offer emergency services, this cannot be said to be higher compared to the facilities in the urban (66.3%), considering that this study considered more urban than rural healthcare facilities. 71.4% of the mission/faith-based facilities offer emergency services compared to 59.3% government and 68.6% private-for-profit. Considering the number of healthcare facilities for this study, one can conclude that private-for-profit health facilities offer emergency services more than government-owned and faith-based healthcare facilities. Only 38.5% of secondary healthcare facilities offer emergency services.

The importance of human health is reflected in the availability of human and infrastructural resources in healthcare facilities. Where these are lacking or in short supply, the few available ones are overcrowded, and it becomes challenging, if not impossible, to attend to the healthcare needs of the people. The study aimed to assess the bed space, referral capacity, and emergency response capacity of the healthcare facilities in Lagos State. The study has revealed that the infrastructure, such as beds, emergency rooms, and emergency transportation services needed to transport patients to other facilities, are lacking in most of the healthcare facilities in Lagos State. Secondary healthcare facilities in the State cannot discharge their roles, especially handling referred patients, as they experience a shortage of bed space to care for in-patients and lack emergency rooms to carter for emergency cases. Lagos State is far below the recommended beds per 1,000 population by the World Health Organisation and even less than the Sub-Saharan average, which indicates that the State healthcare system needs revitalization.

Adequate infrastructural facilities are needed to reposition the healthcare system in Lagos State to cater to its teaming population. Therefore, the local and State governments should prioritize the people's health by providing the necessary facilities at the primary and secondary healthcare levels to function optimally. The government of Lagos State, partners, donors, and all relevant stakeholders in the healthcare sector need to come together to ensure that Lagos state gets the required additional 31,953 hospital beds to reach the recommended five (5) per 1,000 population by the World Health Organization. For equitable distribution of healthcare infrastructure, the local government areas having far less than the State's average of 8 beds per 10,000 population should be given priority attention.

None.

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

©2023 Obubu, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.