MOJ

eISSN: 2379-6383

Review Article Volume 7 Issue 2

1Clinical Psychologist and Professor, Birmingham City University &Stockholm, Sweden

2Clinical Psychologist, Hugh Koch Associates, England

Correspondence: Hugh Koch, Chartered Psychologist, Hugh Koch Associates, Cheltenham, Visiting Professor, Faculty of Law, Birmingham City University & Stockholm University, Sweden, Tel +01242-263715

Received: November 05, 2017 | Published: March 27, 2018

Citation: Koch HCH, Parmar B, Savage J, et al. Understanding customer-supplier chains: - conflict resolution psychology & civil litigation. MOJ Public Health. 2018;7(2):65 – 68. DOI: 10.15406/mojph.2018.07.00207

Developing the theme of how psychology and organisational theory can influence the practice of civil litigation, this paper addresses how the concept of ‘customer-supplier’ chains can apply to conflict resolution in civil compensation claims. The authors unique experience of psychology, quality management and civil claims, offers an innovative insight into how conflicts occur and can be resolved, and how advanced communication skills can be used intentionally to produce ‘win-win’ solutions to legal and medico-legal problems.

Keywords: Customer-supplier chains, psychology, conflict resolutions, impartiality, micro skills, communications, intentionality

Recent articles1–3 have outlined how the many branches of psychology can influence civil law processes there are in relation to the organisational culture of courts and justice, claimant experience, expert experience and experience of judges, barristers and lawyers. Organisational concepts like Continuous Quality Improvement and Therapeutic Jurisprudence, (a positive approach to the delivery of justice), have also been recently considered.4 This innovative paper addresses these concepts further, both psychological and organisational, in the context of two crucial ideas: customer-supplier chains and conflict resolution.

The psychology of customer-supplier chains

In civil litigation, interactions occur between a variety of people, both claimant and professionals, to reach an outcome or settlement for the claimant and insurer. It involves and necessitates coordination and collaboration between each other, involving multi-factorial processes. Many of the exchanges may involve people who have little or no knowledge or interest in the other ‘players’ in the medico-legal supply chain. It is necessary to integrate these several processes and disseminate the awareness and knowledge of these processes to all involved. It attests to the success of civil litigation in the UK that the medico-legal supply chain can cope with change, is resilient, and both claimant and insurer-centric. Those whose career is fully in this area develop flexible supply chains, continuously anticipating and adjusting to ‘crises’, discontinuities and focus, especially, on ultimate and multiple customer-centricity,5 whilst maintaining a responsibility to the court.

What is the medico-legal supply chain?

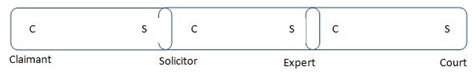

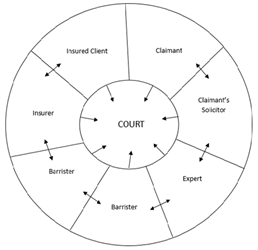

Two images can clearly illustrate how the supply chain operates in civil litigation. We are all ‘customers’ (i.e. expecting a service of high quality from another person(s) and ‘suppliers’ (i.e. expected to provide a high-quality service to someone). However, we typically are concerned and interested in one customer and one supplier directly to each side of our own activities as reflected in Figure 1 below. This figure indicates how, for example, an instructing solicitor has to manage his relationship with both his client and an expert Figure 2.

Positive culture in civil litigation

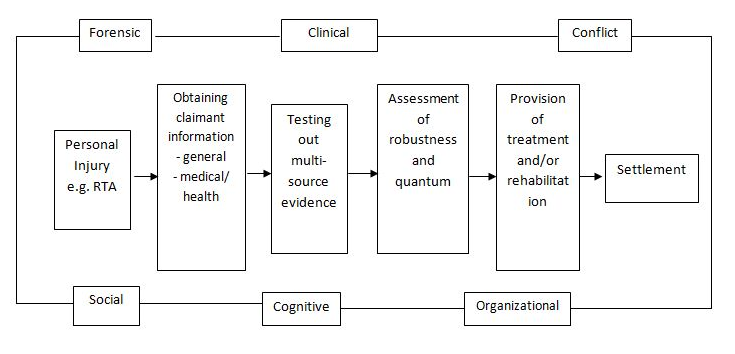

Whether using the professional and ethical language of any one profession (e.g. lawyer, psychologist, barrister) or adopting the language used in quality management practices,6,7 it is widely acknowledged that there are significant benefits for a strong culture of beliefs, values and visions which are both intuitive and supported by psychological and social science. Positive values including the following (Figure 3):

The skills of confrontation: supporting while challenging conflict

It is necessary to confront discrepancies of information, opinions and values in civil litigation. An understanding of confrontation skills is crucial including:

Positive, advanced communication skills

In addition to being an effective and socially skilled communicator, it is important that each person involved in the civil litigation trail can manage the following circumstances sensibly, effectively and wherever possible to mutual benefit with the other person(s) involved.

Typical Problem |

Potential Solution |

|

i. Expert Witness – Claimant |

Listening to claimant; acknowledge their concerns; accommodating new information; maintaining expert opinions whilst simultaneous being seen to take on board claimant’s comments. |

ii. Expert Witness – Instructing Solicitor |

Listening to each other’s viewpoints; Establishing the opinion as robust and unlikely to alter except with new evidence. Maintaining expert’s ultimate responsibility ‘to the court’. |

iii. Case Conference Discussion |

Maintenance of Impartiality Skills9 |

iv. Part 35 Questions and Responses |

Maintenance of Impartiality Skills10 |

v. Expert – Expert Joint Statement |

Highly logical and effective communication between experts and willingness to consider appropriate range of opinions.11 Willingness to consider new evidence. |

vi. Court Hearing |

Importance of professional to accommodate and consider all evidence and range of opinion and to help the court arrive at most robust opinion. |

vii. Post Hearing Conflict |

An understanding by all parties of the complexity of litigation and the role of expert evidence. |

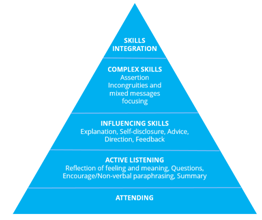

Figure 6 The skills need to reduce problems can increasingly be used ‘intentionally’ and result in ‘win-win’ situations.

This paper continues the first author’s theme in the past 1–2 years of applying psychology and organisational management ideas to the practice of civil litigation and especially medico-legal aspects. Professionals, whether they be experts, solicitors, barristers or judges, encounter conflict regularly in their day-to-day work and have differing levels of communication skills and emotional regulation abilities.12 This paper emphasises the importance of developing a greater ‘intentionality’ in which the professional knows and can elect, consciously, to apply a particular skill to reduce interpersonal tension and conflict in order to arrive, more often, at a ‘win-win’ solution. The idea of the Single Joint Expert (SJE) originally suggested within the Civil Procedure Rules13 back in 1998/9 has never taken off to any substantial extent. When occasionally approved as an S.J.E, such experts experience a different type of communication and impartiality. This role may become more frequent. In the meantime, experts alongside all the other people involved in civil litigation need to understand customer-supplier chains and their effects on conflict resolution. This paper has applied the concept of customer-supplier chains to the specific area of civil claims within personal injury in a UK-based population. Further research could usefully address their specific areas in more detail and with a larger sample, which could also include self-report or psychometric data. It could also usefully address a criminal law sample to compare and contrast fluidity between civil and criminal populations.

None.

None.

©2018 Koch, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.