MOJ

eISSN: 2379-6383

Research Article Volume 6 Issue 1

1Department of Nursing, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Arba Minch University, Ethiopia

2Department of Public Health, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Arba Minch University, Ethiopia

Correspondence: Addisu Alemayehu Gube, Arba Minch University, Ethiopia, Tel +251912119726, Fax +251468810279

Received: April 08, 2017 | Published: June 14, 2017

Citation: Gube AA, Godana W. Quality of care for sexually transmitted infections (STIS) syndromic case management at public health facilities of gamo gofa zone, Southern Ethiopia. MOJ Public Health. 2017;6(1):261–266. DOI: 10.15406/mojph.2017.06.00159

Background: Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs) and their associated complications are regarded as one of the top five reasons for which adults avail themselves for health care services in developing countries.

Objective: This is study was aimed to assess quality of care for STIs Syndromic case management at public health facilities of Gamo Gofa Zone, Southern Ethiopia.

Methods: Facility based cross sectional study that used both quantitative and qualitative methods of data collection was conducted from Jan 1 to Feb 28, 2015. The study included 10 health centers and 2 hospitals selected by simple random sampling, their respective 12 heads, 250 clinicians selected by simple random sampling from the health facilities after proportional allocation to size and 26 mystery clients. The data were entered into EPI info version 7.0.1 and exported to SPSS version 20 for analysis.

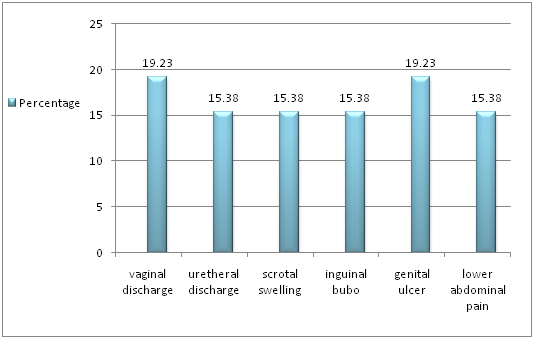

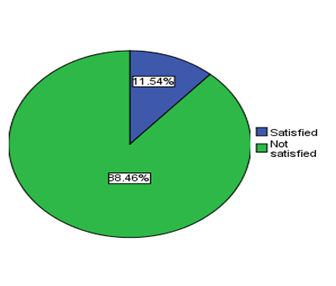

Results: Overall there were no STI Syndromic management guidelines in all health facilities, only 12.8% of clinicians have taken training on Syndromic management of STIs, highest knowledge of clinicians was of urethral discharge (27.2%). Profession of clinicians and type of health facility (AOR= 0.194; 95% CI= 0.092, 0.412) were determinants of urethral discharge knowledge. Only in 8.3% of cards did the clinicians correctly follow the guideline. Only 11.54% of mystery clients were satisfied with the services and only 15.38% will recommend the provider to a friend.

Conclusion: The quality of care for STIs Syndromic case management at public health facilities of Gamo Gofa Zone was poor.

Keywords: STI, std, HIV/aids, syndromic management, quality care, mystery client, gamo gofa zone, gonorrhea, chlamydial infection, syphilis, trichomoniasis, chancroid, genital herpes, hepatitis

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are infections that are mainly transmitted from person-to-person through sexual contact. Almost 30 types of causative bacteria, viruses and parasites have been isolated, which are responsible for multiple STDs such as gonorrhea, chlamydial infection, syphilis, trichomoniasis, chancroid, genital herpes, HIV infection and hepatitis B infection.1,2 They are important because of their magnitude, potential complications and their interaction with HIV/AIDS.3‒6 Even though there is little information on the incidence and prevalence of STIs in Ethiopia, the problem of STIs is generally believed to be similar to other developing countries.4,7 The aim of Syndromic approach is to identify and treat a syndrome with combination therapy which will also take care of the main causative pathogen. Ethiopia has been promoting Syndromic approach since 2001 by adopting the WHO generic guide lines to serve as a national guideline for the management of STIs: since then, trainings on Syndromic approach have been given for health care workers.4,8‒10 The complications caused by failure to diagnose and treat STIs include infertility, congenital abnormality, adverse neurological condition, cardiovascular risks, ectopic pregnancy, anogenital cancer and even premature death of neonates to mention but a few.11,12 One means of reducing the impact of STIs is the management of STIs using the Syndromic approach.4 Many factors play a part in the successful control of STIs, including availability of effective and affordable drugs, accessible and acceptable health services, training and supervision of healthcare workers, and behavioral interventions to prevent new infections by promoting safer sex.13 Quality is measurable. A system is usually made up of three components: input(structure), process and output/outcome.14,15 In order to provide quality care for sexually transmitted infections, Ethiopia has been giving training on Syndromic approach for health professionals but whether the professionals are working accordingly or not need to be explored. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to assess quality of care for sexually transmitted infections Syndromic case management at public health facilities of Gamo Gofa Zone, Southern, Ethiopia.

Study setting

Study was conducted in public health institutions of Gamo Gofa Zone which is located about 505kms South West of Addis Ababa, and about 275km from Hawassa, the capital of the Southern Ethiopian. It has 15 Woredas and 2 Town administrations: within these there are 3 hospitals and 68 health centers. Facility based cross-sectional study design with both quantitative and qualitative methods of data collection was conducted from January 1 to February 28, 2015.

Study population

All public health facilities in Gamo Gofa Zone currently treating STIs, health professionals working there and STI patients in catchment area of these public health facilities.

Sample size and sampling techniques

Sample size was calculated using stat calc program of Epi Info and considering the following assumptions: 18% (knowledge of health care provider),16 95% confidence level and 5% level of precision. Then by adding 10% non-responses rate, the final sample size was found to be 250. For observation, 12 health institutions & 120 STI patient cards were observed and 12 heads of respective health institutions were interviewed. And for mystery clients, total of 26 clients were hired. Of the health facilities in the Zone, 2 hospitals and 10 health centers were selected by SRS technique and sample size was proportionally allocated to health institutions. Then by using cluster sampling all eligible health professionals in the selected health institutions were selected. For mystery client interview, 3 clients/hospital and 2 clients/health centers were interviewed.

Data collection instrument and procedures

For observation, the data were collected using District STI quality of Care Assessment (DISCA) tool17,18 and 12 heads of the health facilities have responded to it. For knowledge assessment, self administered questionnaire which is part of DISCA and for mystery clients, adapted semi structured questionnaire was used.

Data analysis

The data were coded and entered into EPI info version 7.0.1 and data was exported to SPSS version 20 for analysis. Descriptive statistics, vicariate and multivariate analysis was done using binary logistic regressions. Statistical significance was set at P<0.05 and adjusted odds ratio was computed to assess the association between explanatory and outcome variables.

Ethical considerations

Ethical clearance was obtained from ethical review committee of College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Arba Minch University. Permission to conduct the study was also sought from the administrative authority of the respective health institutions. Before enrollment, informed written and verbal consent was taken from respondents.

Socio demographic characteristics

The overall response rate was 100%. Regarding clinicians, 174 (69.6%) were Diploma Nurses, 142(56.8%) were male and More than half of the clinicians, 141 (56.4%) were below the age of 30 years and only quite a small proportion 15 (6%) were at the age of 50 and above. 50% of the clinicians have a median of six years of experience (Table 1).

Variables |

Number (n=250) |

Percentage (%) |

Profession |

||

Diploma Nurse |

174 |

69.6 |

BSc Nurse |

22 |

8.8 |

Health officer |

42 |

16.8 |

Medical Doctor |

12 |

4.8 |

Sex |

||

Male |

142 |

56.8 |

Female |

108 |

43.2 |

Age |

||

Less than or equal to 29 |

141 |

56.4 |

30 to 39 |

70 |

28 |

40 to 49 |

24 |

9.6 |

50 to 59 |

13 |

5.2 |

60 and above |

2 |

0.8 |

Mean+ SD (31.43+ 8.31) |

||

work experience |

||

Less than 1 year |

5 |

2.0 |

1 to 5 years |

115 |

46.0 |

6 to 10 years |

71 |

28.4 |

greater than 10 years |

59 |

23.6 |

Median (6.0) |

||

Table 1 Socio demographic characteristics of clinicians in public health facilities of Gamo Gofa Zone, Southern Ethiopia, Jan 1 to Feb 28, 2015

Structure

Examination facilities

All 12 health facilities have examination coach and only 1 health center has examination light in consultation room which itself was not functional. None of health facilities has vaginal specula in consultation rooms. 10 out of 12 health facilities have examination gloves in consultation rooms. There were no National STI Syndromic management guidelines in health facilities. Client education materials about STI/HIV prevention and treatment were available only in 2 health facilities and were not written in local language. The health centers have on average 3 adult consultation rooms and the hospitals have 3 and 4 adult consultation rooms.

Health personnel

In health centers, the number of clinicians ranged from 17 to 41 with average of 31clinicians in each health center and the total number of clinicians in 10 health centers was 312 where as the number of clinicians in Hospitals was 267. According to the heads, of the clinicians working in health facilities, only 15 (4.8%) and 7 (2.6%) were trained on Syndromic management of STIs in health centers and hospitals respectively. Of the total trained clinicians, 9 (60%) and 3(42.9%) clinicians were working in health centers and hospitals respectively during the study time. But of 250 clinicians participated in the study, only 32 (12.8%) were trained on Syndromic management of STIs and 50% of these had received their training before a median of 4.5 years prior to this study.

Knowledge of clinicians

Of 250, clinicians who mentioned the name of the drug, dosage, frequency and duration correctly according to National guideline were for urethral discharge 68 (27.2%), for vaginal discharge 48 (19.2%), for genital ulcer 5 (2%) and for pregnant women with vaginal discharge only 4 (1.6%) (Table 2). And finally clinicians who mentioned the name of the drug, dosage, frequency and duration correctly for the drug in place of doxycycline for discharge management were 75 (30%). Further analysis to assess determinants of knowledge of urethral discharge shows that profession of clinicians and type of health facility they were working in were significant determinants (Table 3). Health officers have knowledge of urethral discharge 4 times more likely than Diploma Nurses (AOR= 4.326; 95% CI= 2.019, 9.268). Likewise the odds of having knowledge of urethral discharge for Medical Doctors was 8 times higher than Diploma Nurses (AOR= 7.788; 95% CI= 2.021, 30.006). And clinicians working in Health Centers have knowledge of urethral discharge 5 times more likely than clinicians working in Hospitals (AOR= 0.194; 95% CI= 0.092, 0.412).

Knowledge of Syndromes |

Trained (32) |

Untrained (218) |

Total |

Has Knowledge of Urethral Discharge |

|||

Yes |

12 (37.5%) |

56 (25.7%) |

68 (27.2%) |

No |

20 (62.5%) |

162 (74.3%) |

182 (72.8%) |

Has Knowledge of Vaginal Discharge |

|||

Yes |

5(15.6%) |

43(19.7%) |

48(19.2%) |

No |

27(84.4%) |

175(80.3%) |

202(80.8%) |

Has Knowledge of Genital Ulcer |

|||

Yes |

1(3.1%) |

4(1.8%) |

5(2.0%) |

No |

31(96.9%) |

214 (98.2%) |

245(98.0%) |

Has Knowledge of Pregnant Women with Vaginal Discharge |

|||

Yes |

2(6.2%) |

2(0.9%) |

4(1.6%) |

No |

30(93.8%) |

216(99.1%) |

246(98.4%) |

Table 2 Clinicians knowledge of treatment for STI syndromes: trained and untrained in public health facilities of Gamo Gofa Zone, Southern Ethiopia, Jan 1 to Feb 28, 2015

Determinants |

N (%) |

Have Knowledge N(%) |

Crude Odds Ratio |

Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

Profession of Clinicians |

||||

Diploma Nurse |

174 (69.6) |

39 (22.4%) |

1 |

1 |

BSc Nurse |

22 (8.8) |

2 (9.1%) |

0.346(0.78,1.546) |

0.427(0.092,1.987) |

Health Officer |

42 (16.8) |

22 (52.4%) |

3.808(1.886,7.688)* |

4.326(2.019,9.268)* |

Medical Doctor |

12 (4.8) |

5 (41.7%) |

2.473(0.743,8.223) |

7.788(2.021,30.006)* |

Type of Health Facility Clinicians Working in |

||||

Health center |

138(55.2%) |

52 (37.7%) |

1 |

1 |

Hospital |

112(44.8%) |

16 (14.3%) |

0.276(0.147,0.518)* |

0.194 (0.092,0.412)* |

Table 3 Determinants of knowledge of urethral discharge in public health facilities of Gamo Gofa Zone, Southern Ethiopia, Jan 1 to Feb 28, 2015

*= significant results

STI Drug Availability

It is all in Table 4

Drug |

Currently in Stock? |

Currently Out of Stock? |

In Stock in Last Month |

Out of Stock in Last Month |

||||

Number |

% |

Number |

% |

Number |

% |

Number |

% |

|

Ciprofloxacin |

12 |

100 |

0 |

0 |

11 |

91.7 |

1 |

8.3 |

Metronidazole |

12 |

100 |

0 |

0 |

12 |

100 |

0 |

0 |

Doxycycline |

12 |

100 |

0 |

0 |

12 |

100 |

0 |

0 |

Benzanthine Penicillin |

11 |

91.7 |

1 |

8.3 |

11 |

91.7 |

1 |

8.3 |

Spectinomycin |

8 |

66.7 |

4 |

33.3 |

8 |

66.7 |

4 |

33.3 |

Tetracycline |

6 |

50 |

6 |

50 |

5 |

41.7 |

7 |

58.3 |

Erythromycin |

11 |

91.7 |

1 |

8.3 |

11 |

91.7 |

1 |

8.3 |

Acyclovir |

8 |

66.7 |

4 |

33.3 |

8 |

66.7 |

4 |

33.3 |

Table 4 The drug supply for the syndromic management of STIs in 12 public health facilities of Gamo Gofa Zone, Southern Ethiopia, Jan 1 to Feb 28, 2015

Structural quality

The above findings indicate that the structural quality in all 12 health facilities for treatment of STIs syndromically was poor.

Services for STI patients

All health facilities do not provide services for STI patients privately. In 11 (91.7%) of health facilities, RPR testing is done on site in the facility. In 7(58.3%) health facilities, there was no occasion over the last month condoms ran out and 8(66.7%) health facilities do not show STI clients how to use condom in their facility. 9 (75%) health facilities have penile model for condom demonstration in their facility. Only 2 (16.7%) health facilities have condoms put in some place in the compound of the facility for individuals who want to use it. 11 (91.7%) health facilities do not have partner notification cards in their facility and only 1 (8.3%) health facility has partner notification card. Concerning syphilis screening on pregnant mothers, in only 7(58.3%) health facilities it was done for all pregnant mothers who come to health facility for ANC first visit. Of the total reviewed 120 cards of STI patients, only in 10 (8.3%) cards did the clinicians correctly followed the national guidelines and treated the patients correctly using the Syndromic approach.

Process quality

The above findings indicate that the process quality for treatment of STIs syndromically in all 12 health facilities was poor.

Output

Of 26 mystery clients, only 1 (3.8%) mystery client was asked to show the diseased part for physical examination. For them, the maximum waiting time was 3 hrs and the minimum waiting time was 2 minutes. And 50% of clients have waited for 15 minutes. About the length of time they waited to the see the provider, 15 (57.69%) said not satisfied and the left 11 (42.31%) said they were satisfied. On the other hand, the maximum time they spent with provider was 30 minutes and the minimum was 2 minutes. And the mean time they spent with provider was 15.46 minutes. When asked about the length of stay with the provider, 16 (61.54%) said not satisfied and the other 10 (38.46%) said satisfied. The number of clients greeted by the provider when arrived in consultation room was only 7 (26.92%). In consultation room only 8 (30.77%) clients were satisfied with the provider’s behavior. And only 7 (26.92%) received advice. 20 (76.92%) said they were not satisfied with the privacy of the service. Only 8 (30.77%) were told to bring their partner and 20 (76.92%) said they weren’t asked by the provider to return for another visit. Regarding the overall satisfaction with the consultation session, majority 23 (88.46%) said they were not satisfied (Figure 1 & 2). Concerning recommending the provider to a friend, majority 22 (84.62%) said they will not recommend.

Output quality

The above findings indicate that output quality for management of STIs syndromically in all 12 health facilities was poor.

Structural quality

According to HIV/AIDS Prevention and Control Office, In order to treat STI patients, National STI Syndromic management guidelines should be available in all public health facilities of Ethiopia.4 But findings of this study show that there were no guidelines in all health facilities. This is consistent with the finding of study conducted in Zaria, Northern Nigeria which showed no center had the Syndromic management manual or chart.19 However, this finding is far lower than that of the finding from study conducted in South Africa where 3 out of 4 Regional clinics have guideline in each consultation rooms.20 This may be attributed to the fact that South Africa has been working hardest to control STIs more. In order to follow the guideline and treat patients accordingly, clinicians have to have training on Syndromic management of STIs but in our study only 12.8% of clinicians were trained. This finding is higher than that of the finding from the study conducted in Windhoek, Namibia among private General Practitioners where none of them had specific training on Syndromic management.12 This could be attributed to our study was among clinicians working in public health facilities where government give priorities whereas the study in Namibia was among clinicians working in private health facilities. However, the finding from this study is completely below the finding of the study conducted in South Africa where all clinicians working in 3 out of 4 clinics were trained.20 In this study even if overall knowledge of clinicians varied by syndrome type it was all lowest that is the maximum knowledge the clinicians have was about treating urethral discharge that was 27.2%. This result is lower than that of the study conducted on KAP of General Practitioners in Karachi, Pakistan and among private General Practitioners in Windhoek, Namibia where the knowledge for urethral discharge was 55.3% and 56.5% respectively.21,12 This might be because of these studies only focused on knowledge of General Practitioners while our study included lower level clinicians like Diploma Nurses also.

Process quality

In this study of the total reviewed 120 cards of STI patients, only in 10(8.3%) cards did the clinicians correctly followed the national guidelines and treated the patients correctly using the Syndromic approach.

This finding is almost consistent with the finding of the study conducted in Pakistan where most providers practiced personal empiricism.22 However, this finding is slightly lower than the finding of the study conducted in six countries in West Africa where effective treatment was given to 14.1% of patients in conformity with national Syndromic STD management algorithms.23 This might attributable to the fact that this study covers the health facilities in six countries in West Africa which may include specialized health facilities while our study only included public health facilities in Gamo Gofa Zone of South Ethiopia. Similarly in the study, of 26 mystery clients, only 5(19.23%) were treated correctly according to the National guideline. When seen superficially, this finding seems to be a little bit higher than the finding of the study conducted in Pokhara, Nepal where chemists and druggists treated correctly according to guideline in 10.8% of simulated client cases24 but in fact chemists and druggists were not allowed to treat patients expect referring them to doctors. So the finding of the current study shows low performance according to national guide line.

Output quality

Of 26 mystery clients seen, only 1(3.8%) of mystery client was asked to show the diseased part for physical examination. This finding is far behind the finding of the study conducted in six countries in West Africa where an adequate physical examination was carried out in 60.8% of cases.23 This might be because this study shows the findings from health care facilities in six West African countries while our study only shows the finding from public health facilities of a single Gamo Gofa Zone in South Ethiopia. In this study, of the mystery clients participated in the study, 57.7% were not satisfied with the length of time they waited to see the provider. This finding shows large number of clients not satisfied with the length of the time compared to the finding of the study conducted in Abidjan, Co ˆte d’Ivoire where 44% of interviewed clients complained about a long waiting time.24 This might be attributed to the fact that since participants in study conducted in Co ˆte d’Ivoire were female sex workers, in steady of complaining of the time they may shift to other health facilities where as the participants in current study were member of general population who may wait and complain of time rather than rushing to other health facilities. In this study the number of mystery clients greeted by the provider when arrived in consultation room was only 7(26.9%) and the number of those satisfied with the provider’s behavior in consultation room was only 8(30.77%). This finding is far lower than the finding from the study conducted in Pokhara, Nepal where the providers talked with patient with a friendly face in 73% of simulated client, gave attention and showed interest in 83.8%.25 This might be because this study was done on health workers post training where as our study was done on health professionals randomly. In current study, of mystery clients seen in health facilities, only 23.1% were satisfied with the privacy of the service. This finding is similar with the finding of the study conducted in Pakistan where no public facility had enough space/privacy to effectively counsel clients on behavioral risk reduction.22 In the study, of mystery clients seen in health facilities, only 30.77% were told to bring their partner. The finding is higher than the findings of the study conducted in Pakistan where Partner treatment was never discussed or administered22 and Windhoek Namibia where when managing a male patient on medical aid with urethral discharge for the first time, only 26% Doctors prompt partner notification.12 Whereas the finding is lower than the findings of the study conducted in Pokhara, Nepal where chemists and druggists notify the partner of the patient in 43.2% of simulated client24 and six countries in West Africa where patients were encouraged to advise their partners to seek treatment in 50.8% of cases.23 This might be because of the study in Pokhara, Nepal was done on health workers post training and for the study in six countries in West Africa, the study shows the findings from health care facilities in six West African countries. In this study, of mystery clients, only 11.54% were satisfied with the services and only 15.38% will recommend the provider to a friend. This finding is far lower than the finding of the study conducted in Abidjan, Co ˆte d’Ivoire where most clients were happy with the clinic and with the attitude of the health care provider, and would return to the same place for the next health problem.25 This could be attributable to the fact that these health facilities in Abidjan, Coˆted’Ivoire were the facilities female sex workers chosen for themselves and made a regular customer where as in current study the mystery clients were gone to random health facilities.

In general the study indicated that quality of care for Sexually Transmitted Infections syndromic case management at public health facilities of Gamo Gofa Zone was poor which may be explained by the lack of National STI syndromic management guidelines, examination lights and vaginal specula in health facilities, inadequate knowledge of clinicians, inability of clinicians to treat STI patients correctly and unsatisfied clients.

Our sincere thank goes to Arba Minch University for provision of the opportunity to conduct the research. We also like to give our deepest gratitude for Gamo Gofa zone health departments for providing baseline information. Lastly our thanks go to data collectors and all research participants who took part in the study, without whom this research wouldn’t have been in to existence.

Author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

©2017 Gube, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.