MOJ

eISSN: 2379-6383

Research Article Volume 5 Issue 5

Department of Pediatric Surgery, Saint Louis University and Cardinal Glennon Children

Correspondence: Yana Puckett, Department of Pediatric Surgery, Saint Louis University and Cardinal Glennon Children’s Medical Center, USA, Tel 7067210427

Received: April 07, 2017 | Published: May 3, 2017

Citation: Puckett Y. Reassessing post-hospital conditions of section 3025 hospital read missions reduction program in the affordable care act. MOJ Public Health. 2017;5(5):176–181. DOI: 10.15406/mojph.2017.05.00144

The Patient Protection and Affordability Care Act (PPACA) brought many changes to the delivery of the U.S. Health Care System since its inauguration on March 23rd, 2010 (Medicare & Services, 2013a). A change within the Affordable Care Act (ACA) is Title III, part III, Section 3025 policy, adopted in 2012. This policy implemented the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) requiring the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to reduce payments to hospitals with higher than expected 30day readmission rate for acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia. Hospitals with higher-than-predicted readmission rates have their total Medicare reimbursement for fiscal year reduced by up to three percent based on these calculations. This paper reviews the policy in detail and proposes changes that need to be made to the policy to avoid penalizing hospitals unnecessarily.

Keywords: medicare services, medical diagnoses, heart failure; pneumonia, medication reaction, improper discharge instructions, sleeplessness, bedsores, infections, COPD

PPACA, patient protection and affordability care act; ACA, affordable care act; HRRP, hospital readmissions reduction program; CMS, centers for medicare and medicaid services; GDP, gross domestic product; AHRQ, agency for healthcare research and quality; Med PAC, medicare payment advisory committee; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; THR, total hip replacement; TKA, total knee arthroplasty; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary Disease; AHA, american hospital association; IHA, Illinois hospital association

The U.S. spent an average of $9,086 per person on health care in 2013, which translated to more than 17% of the gross domestic product (GDP). This has been the trend in U.S. health care spending for over a decade. Despite the U.S. having the highest health care cost in the world, the health outcomes in the U.S. are ranked 22nd out of the 23 developed nations.1 A contributor to the high health care cost in the U.S. is hospital readmissions. According to several sources, approximately 20% of hospital readmissions were estimated to be potentially avoidable.2‒6 The Medicare Payment Advisory Committee (Med PAC) estimated that of the 20% of Medicare discharge readmissions, 12% of these could be prevented. Med PAC’s study concluded a potential to save Medicare $12billion of the total $15 billion in health care costs due to readmissions (Med PAC, 2014). A study on hospital readmissions conducted by the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) reported a spending of $17.4 billion for unplanned re hospitalizations from a total $102.6 billion spent in hospital payments by Medicare in 2004. NEJM also suggested 78.5% of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries were re hospitalized for medical diagnoses; with heart failure, pneumonia, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease being the most prevalent diagnoses for readmission.7

In addition to the high financial costs of re-hospitalization, readmissions is also associated with poor health care quality and causes detrimental health effects to the elderly, who are readmitted more often.8,9 Post-hospital Syndrome is a condition, occurring within the first 30days of hospital discharge, whereby the readmission medical diagnosis is different from the initial cause of hospitalization. Reasons for Post-hospital Syndrome include adverse medication reaction, improper discharge instructions, sleeplessness, bedsores, infections, and the negative impact on mental health.8 Studies show hospital readmissions not only occur due to clinical reasons. Lack of coordination and communication within the health care system itself also plays a big role.10

Data from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) estimates the hospital cost of preventable readmissions during 6months amounts to approximately $730 million dollars. Risk factors for high readmission rates include the social determinants of health, lower socioeconomic status of patients, and minorities.11 The data is consistent across the United States and affects millions of people.

Medicare defines readmission rates as:

Patients who are admitted to the hospital for treatment of medical problems sometimes get other serious injuries, complications, or conditions, and may even die. Some patients may experience problems soon after they are discharged and need to be admitted to the hospital again. These events can often be prevented if hospitals follow best practices for treating patients (CMS, 2013). High readmission rates within 30days of discharge have been synonymous with inadequate treatment and post-discharge follow up care, high complication rate from the treatment received by hospital stay, and a high mortality rate.11

A related policy initiative involved direct payment incentives for providing high quality of health care.12 Pay-for-performance directly incentivizes quality by making a portion of payments to providers or hospitals dependent on quality-related outcomes. Medicare’s current payment system places no emphasis on whether the care delivered is of high or low clinical quality or is appropriate. The system provides few disincentives for overuse of often high cost medical services and does little to encourage coordinated, preventive, and primary care that could save money and produce better health outcomes. Pay-for-performance incentives, which reward providers for delivering high quality care, are thought to help speed the process of implementing best practices.

This policy did not result in better performance however, as it did not lead to reaching those goals of high health care quality based on given metrics. Some have sighted this failure to difficulty in changing physician behavior and even when physician behavior changed, it did not lead to quality.13 The continued rise in costs of readmission, negative impact of readmission on health, and the potential to save CMS 75% in hospital readmission spending led to the development to section 3025.14

The primary goal of Section 3025 is reducing hospital readmission rates. Incremental goals of CMS spending reduction and improving quality of health care will help fulfill the primary goal of Section 3025. A discussion on the goals of Section 3025 is outlined below.

Goal 1: Reduce hospital readmission rates to achieve readmission reduction, medical conditions with a high readmission prevalence and cost are included in the metric system of Section 3025. In 2013, the medical conditions penalized for excessive 30-day hospital readmissions included Pneumonia, Acute Myocardial Infarction (AMI), and Heart Failure. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), Total Hip Replacement (THR), and Total Knee Arthroplasty (TKA) are additional conditions added to the metric in 2015.15

Constraints: Section 3025 lacks political support and acceptability from healthcare related interest groups such as American Hospital Association (AHA), Illinois Hospital Association (IHA), and Healthcare Association of New York State (HANYS). Many hospitals disapprove the metric used to calculate the 30-day readmission penalty fee in Section 3025. Criticism include unfairly penalizing hospitals without considering the hospital’s teaching status, inner-city location, rural location, and safety-net status.16

Evaluation criteria: The reported 20% readmission rate by Med PAC will be used as a baseline for comparison while the reported 12% preventable readmissions will be used as the end goal of Section 3025 (Med PAC, 2014). The percentage decrease analyzed by the CMS Office of Information Products and Data Analytics will determine the effectiveness of Section 3025 in reaching its intended goal.

Goal 2: Reduce CMS spending the collection of penalty fees incurred to hospitals with high readmission rates will reduce CMS spending. CMS will use these savings to reduce Medicare Part B premiums by up to $200 annually by 2019.15,17

Constraints: There is a lack of political support and acceptability from interest groups and providers since the penalization hospitals incur leads to a loss of hospital revenue.

Evaluation criteria: The Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) analyzes the Hospital Readmission Reduction Dataset reported by Medicare. The analysis estimates the total CMS penalization, the percentage of total hospitals penalized, and a percentage of hospitals incurring the maximum penalization. The reduction in CMS spending determined by the KFF analysis will be compared to Med PAC’s reported spending reduction of $1.2billion a year for CMS. Reports obtained from CMS on changes or reductions in Medicare Part B premiums will clarify if CMS is reaching its intended goal of premium reduction.

Goal 3: Improve quality of health care. Medicare’s Quality Improvement Organization (QIO) assists hospitals in reducing readmissions by improving coordination of care and communication between patients, providers, and long-term care facilities.18 Enhancing coordination and communication creates a smooth transition of care, decreases medical errors, provides for better patient experience, and improves quality of care (QIO, 2015).

Constraints: There is a lack of administrative feasibility and a high cost of EHR implementation. The high cost of installing an EHR system to improve care coordination may dissuade hospitals from reducing readmissions and accept the penalty. For example, safety-net and rural hospitals may not have the financial resources to utilize EHR systems to reduce readmissions and thus be penalized through Section 3025.19 If the penalization cost is lower than the cost of preventing readmissions or installing an EHR system, the hospital may decide to accept the penalty instead.20

Evaluation criteria: An analysis completed by the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) on the effectiveness of CMS’s QIO initiative in reducing readmission rates is reviewed. The effectiveness of other initiatives indirectly supporting the goals of Section 3025 is also discussed.

Current policy

Section 3025 financially penalizes hospitals with high readmission rates to prevent future readmissions and decrease CMS spending.21 The policy makes hospitals accountable for the care it provides on a national level and shifts the focus of hospitals nationwide from a fee-for-service to patient centered outcome care.22,23 The high volume and costs of the conditions incorporated into the metric system provides room for readmission reduction and CMS health care spending.24 The metric system used by the Therefore, a policy alternative is not needed; instead, policy modifications needs to be made.

The main modification to be made is altering the metric system to take into account socioeconomic factors of the population being served, status of the hospital (teaching, large, safety-net, rural), and the medical complexity of the patients. For example, hospitals with majority of patients with multiple comorbidities may not be fairly penalized with other hospitals serving a much healthier population to the “30” day hospital readmission rate. For these hospitals, the readmission rate needs to be adjusted to be more lenient. In addition, a different metric must take into account the medical complexity of the patient as well as the social determinants of health. Teaching hospitals have a higher readmission rate compared to non-teaching hospitals while geographic variation of hospitals impacts the demographics of population served. Teaching hospitals often exist in urban regions with a large and medically complex population.18,25‒27 Data does not support poor decision making by the provider accounts for higher than average readmission rate compared to nonteaching hospitals, but rather the availability of resources was cited as an explanation when adjusting for age, race, sex ("Community collaboration helps cut readmits," 2012).

The metric should also account for poor neighborhood hospitals serving a more indigent population which tends to be more medically complex.28,29 This can be attributable to many factors not related to provider treatment such as disease epidemiology and patient lifestyle habits.

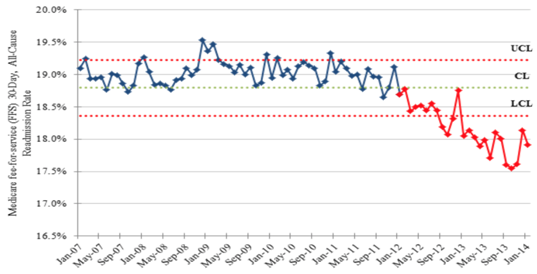

Goal 1 Evaluation: The policy, in just two years of implementation, has successfully reduced hospital readmission rates by two percent. The first year Section 3025 was enacted, the readmission rate among Medicare beneficiaries fell from 19.5% to 18.5% or approximately 150,000 fewer hospital readmissions. As shown in Figure 1 below, during the second year, from 2013 to 2014, the readmission rate declined another percent from 18.5% to 17.5%.15 Although the two percent decline in readmissions does not correlate with a full reduction of MedPAC’s estimated 12% preventable readmissions, the decline supports the effectiveness of Section 3025 in meeting its intended goal17 and is likely on its way to achieve the 12% readmission goal with time.

Figure 1 Medicare fee-for-service, all-cause, and 30-day readmission rates. CL indicates control limit; LCL, lower control limit; and UCL, upper control limit. Copyright 2014 by US Department of Health and Human Services. Reprinted with permission.

Goal 1 Violations: An analysis on the success of Section 3025 made by Joynt and associates used the publicly available HRRP Supplemental Data File to evaluate the types of hospitals being penalized. Of the 3,282 hospitals analyzed, approximately 67% received payment cuts as a result of Section 3025.16 While large hospitals were more likely to be penalized compared to smaller hospitals, smaller hospitals were less likely to receive payment cuts.

Small hospitals tend be privately owned with for-profit status. In addition, teaching hospitals were found more likely to be penalized than nonteaching hospitals along with safety-net and rural hospitals. A safety-net hospital or health system provides a significant level of care to low-income, uninsured, and vulnerable populations.28‒30 Thus, this review is evidence that hospitals serving high-risk populations are being penalized more than private owned, for-profit hospitals.31 It is unclear why non-profit, large hospitals, safety-net hospitals, rural and teaching hospitals are receiving higher penalties under Section 3025, but studies suggest it is likely due to the medical complexity of the patient and socioeconomic factors of the patient population.32,33

Goal 2 Evaluation: From 2013 to 2015, CMS collected approximately $290, $227, and $428 million, respectively, in total penalties. The penalties collected supports the effectiveness of CMS’s goal to reduce spending as CMS regains some of the cost they spent on health services. The significant rise in penalty collection for the fiscal year 2015 was due to the addition of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) and Hip or Knee replacement measures to the metric in Section 3025. For example, estimates indicate a $66 million net penalty collection by CMS for COPS readmissions alone.24 In addition to these conditions, there was an increase of 385 penalized hospitals (Kaiser, 2015). Though the collected penalties failed to reach the intended $1.2 billion in cost reduction, the addition of more conditions in 2017 will aid CMS in achieving its goal.17

The reduction in CMS spending over the past three years has yet to reach its incremental goal of lowering Medicare Part B premiums. Medicare premiums have remained unchanged as noted by the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Sylvia Burwell.15 CMS has decreased spending through penalty fee collection, however, evaluating CMS’s incremental goal of reducing Medicare premiums is too soon as the projected timeframe to reach this goal is still four years away.

Goal 2 Violations: The goal of reducing CMS spending violated political support and acceptance of the policy as the policy leads to a loss of revenue. Payment cuts have been made on approximately 67% of all the hospitals in the U.S. with highest penalizations going to safety-net hospitals, rural hospitals, large hospitals, and teaching hospitals.16 The rural hospitals had the highest average penalty rate of 0.50% in 2013 of which 65% of all rural inpatient prospective payment system (IPPS) hospitals were penalized.

Large hospitals faced a slightly lower penalty fee of 0.36% of which 69% of all large hospitals were penalized in 2013. A three percent penalty to rural hospitals, which have an average revenue income of $10million, could be $300,000. A $300,000 loss in revenue is a significant cost that would have otherwise been used for patient care (Licht, 2013). Although rural hospitals tend to provide services to the population’s most disadvantaged patients with limited resources, Section 3025 is penalizing these hospitals with the highest penalty fee.34

Goal 3 Evaluation: Section 3025 did succeed in lowering readmissions and CMS spending but failed to improve quality. While patient quality improved for non-readmitted patients, the policy failed to improve care coordination and communication (Brock, 2013). Implementing and maintaining Electronic Health Records (EHR), which helps prevent readmission by improving health care information transfer among acute and sub-acute facilities, comes at a high cost that Section 3025 does not provide resources for. The estimated cost for such a system is around $250,000 with an annual maintenance cost of over $85,000 (AHRQ, 2011). A cost-effective analysis evaluating readmission rate reduction with EHR implementation is warranted.

Even though CMS does not provide resources for hospital interventions and care restructuring aids in reducing readmissions, CMS provides funding to other ACA efforts in improving transition of care to achieve the goals of Section 3025. The Community-Based Care Transition Program (CCTP), section 3026 of the ACA, provides $300 million to qualifying hospitals in improving patient care transition between health care facilities and providers while decreasing readmission rates (CMS, 2012). Another program indirectly supporting the goals Section 3025 is called the Transitional Care Management Services (TCMS). TCMS streamlines the transition of care for highly complex patients and for patients lacking decision making capability. It also facilitates the care of the patient from a hospital setting to a community setting, such as the patient’s home or assisted living. Although CCTP and TCMS aim to improve quality of care, they require hospitals to have full integration of inpatient and outpatient care to counterbalance the penalty by Section 3025.15 Results from the JAMA analysis on the effectiveness of the QIO initiative showed an insignificant reduction in all-cause 30 day re-hospitalizations as a percentage of hospital discharges (Brock, 2013).

Goal 3 Violations: Section 3025 violated the constraint of hospital acceptability and political support. Failure of CMS to address this constraint, hospitals have to decide on whether to abide by the policy rules. Some hospitals may accept the penalty if the cost of readmission prevention is greater. Since the penalty fee is capped at a percentage of payments from acute inpatient care, the penalization may be less than the cost of re-hospitalization prevention (Naylor, 2015). Given the penalty fee is not significantly detrimental to the hospital’s income or if the income received from re-hospitalizations due to conditions other than those measured in Section 3025 is greater, the hospital may choose to accept the penalty (Stone & Hoffman, 2010).

Since its inception, Section 3025 has enjoyed moderate success. The latest data from the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) data shows a 2% decline in readmission rates from 19.5% to 17.5%. However, the policy has room for improvement. Once public reporting and payment penalties to reduce readmission rates were implemented, criticism poured in from hospitals, professional societies, and independent organizations. Section 3025 has been criticized for one main issue: the metric system penalizes hospitals for readmission within 30days does not accurately take into account various factors behind those readmissions. To be specific, it harshly penalizes hospitals serving indigent populations lacking access to care. The metric also penalizes hospitals serving populations with complex medical problems, rural hospitals, and teaching hospitals. Penalization of such hospitals leads to loss of revenue for hospitals needing it most and pressuring hospitals to forego patient safety to preserve reimbursement.32 This decreases the quality of hospital facilities, depletes resources and manpower, and results in worse outcomes for patients.19

The current metric is also criticized for being too rigid. The fixed “30” day rule applies to every hospital without taking into account socioeconomic factors, location of hospitals, available resources of the hospital, rural versus urban population, and the health status of the population the hospital serves.19 The proposed amendment to Section 3025 is politically feasible, but may receive some resistance to implementation from CMS. Both Republicans and Democrats should support the amendment, as it would continue to decrease health care spending by decreasing the rate of readmission by continuing to penalize hospitals under performing as per the new metric. Likewise, the CMS should not be opposed to the amendment, as it will keep Medicare spending low. However, because hospitals are likely to be penalized less with implementation of the new metric; Medicare will have to pay more money for healthcare. This is especially true in light of the rise in the aging population.. This may cause CMS to resist passing the amendment to change the metric. Interest groups such as the American Medical Association (AMA) and the AHA are likely to support the amendment for the metric system to more accurately assess readmission rates. With the current Section 3025 metric failing to account socio demographic factors depriving the neediest hospitals and patients; the AHA stated “Section 3025 was flawed and must be reformed to account for socioeconomic factors of communities and appropriately exclude unrelated readmissions that are not related to the initial admission” (AHA, 2014). Section 3025 was established with the goal of improving health care for Americans by making hospitals accountable for their readmissions. Hospitals are penalized if their readmission rate is too high. The policy amendment recommended in this paper is politically feasible as it supports the underlying goals of the ACA, namely improvement in quality of health care in the United States and promotion of safety. The recommendations made in this paper are not overarching of the crux of Section 3025.

An analysis of Section 3025 key stakeholders including patients, CMS, and providers is discussed in greater detail below.

Section 3025 winners: With the current Section 3025, patients receiving care for conditions stand to benefit by receiving better health care by their providers with aim to reduce readmission. The increased caution by providers will ensure minimizing the risk of patient readmission, improve patient discharge instructions and health outcomes, and enhance transition of care (KFF, 2015). Through Section 3025, CMS stands to gain with the reduction in patient readmissions and health care spending. With a reported $290, $227, and $428 million in penalties collected over the past three years, CMS has saved a total of $945 million. Since CMS does not reward hospitals for having a low readmission rate while making hospitals aware of the penalization, CMS will continue to see a decrease in health care spending and a reduction in readmission rate (KFF, 2015). Although CMS has seen a reduction in spending, the associated cost expenditure from an increase in Medicaid beneficiaries through the ACA and Medicare, will lead to an increase in CMS health care spending (CMS, 2014).

Section 3025 losers: Patients receiving care at a disadvantaged hospital may receive low quality of care due to lack of hospital resources. With the exclusion of socio demographic factors, the metric used by Section 3025 has garnered much criticism from hospitals in penalizing hospitals for uncontrollable factors. The Illinois Hospital Association (IHA) opposed Section 3025 and stated “IHA strongly recommends CMS amend the HRRP to adjust patient readmissions that are influenced by demographic factors and other circumstances resulting in readmissions that are beyond the hospital's control”.17 The President and CEO of BJC HealthCare, Steven Lipstein, said hospitals lose through the Section 3025 by “diverting money away from teaching and safety-net hospitals that care for disadvantaged patients, the hospital readmission reduction program has the unintended consequence of worsening disparities between rich and poor”.35 Hospitals, in particular safety-net and teaching hospitals, falter due to the high penalty fees incurred from having a high readmission rate. The added financial burden to these hospitals causes a reduction in health care services or can lead to hospital closures.35 The reduction in a patient’s access and quality of health care due to Section 3025 further undermines the goal of the ACA.

Physicians will indirectly lose due to Section 3025. A physician employed at a rural hospital may have a reduction in salary or be laid off if the hospital does not have the financial resources to staff their salary due to a large penalty fee. Section 3025 causes physicians to lose their autonomy as more regulations impacting their medical judgment are finalized.

Proposal winners: With the proposed policy amendment, patients receiving care at underprivileged hospitals will benefit through the increased available hospital financial resources and access to care.35 Patients will receive higher quality of care by not being discharged sooner than later. Health care facilities, specifically safety-net hospitals, will benefit with AHA’s proposal for Section 3025. The consideration of patient socio demographic and socioeconomic factors in the policy’s metric system will decrease the impact of Section 3025 to disadvantaged hospitals, and narrow the gap between health care and socioeconomic disparities. The AHA’s policy proposal would also increase hospital support as “the inclusion of socioeconomic factors would acknowledge the reality that hospitals cannot always control or change structural barriers to accessing resources that can help prevent readmissions”.17 The reduced financial burden on safety-net hospitals will improve medical care for the disadvantaged population. This in turn, will increase overall health care outcomes and health care quality in the United States propelling it to the top of the list of best health care providers in the developed countries. The amendments to Section 3025 will help physicians retain their autonomy and trust on behalf of their medical decisions.

Proposal losers: Medicare beneficiaries may also see a decrease in their insurance benefits or an increase in premiums due to the reduction in the penalty collection by CMS. The proposed Section 3025 metric modifications will further lead to a loss of revenue for CMS. With the penalty metric accounting for socioeconomic factors, CMS will have a reduction in the hospital penalties collected.36 Through the decrease in penalty collection and an increase in Medicare beneficiaries, CMS may have to charge higher Medicare premiums or provide less benefits to the beneficiaries.37‒48

Section 3025 of the ACA has made hospitals accountable for the care it provides on a national level. It has also shifted the focus of hospitals nationwide from fee-for-service to patient centered outcomes care. In addition, it has resulted in decreased health care spending by CMS. However, analysis of the most likely hospitals penalized shows rural, large, inner-city, teaching, and safety-net hospitals are penalized the highest amount. They are also penalized unfairly as the current metric system does not take into account the medical complexities and socioeconomic factors of the patient population served. Such unfair penalization is leaving hospitals needing revenue the most with net losses. This in turn decreases health care quality in the United States – a contradiction to ACA overarching goals. Racial disparities, medical complexity of patients, and social determinants of health are all factors influencing readmission rates. The current metric system adjusting for readmission rates is flawed as it penalizes hospitals serving medically complex patient populations. The metric system for readmission rate needs to be modified to include socioeconomic factors and medical complexity of patients the hospitals requiring the most support and resources do not get penalized erroneously. Further analysis needs to be made on how to develop a metric system taking into account the complexities of medical population being served as well as the role of socioeconomic factors. Adjusting the metric to reduce penalization of large, inner city hospitals, rural hospitals, teaching hospitals, and safety-net hospitals will improve health care quality and safety of medicine in the United States to match other developed nations. The inclusion of socio demographic and socioeconomic factors in AHA’s proposed policy provides a means to reduce health care disparities, improve access and quality of health care for patients, and realigns Section 3025 in reaching the goal of the ACA. While the current Section 3025 negatively affects stakeholders such as health providers and patients, the proposed AHA policy decreases the impact of Section 3025 to stakeholders. AHA’s proposal also continues to strive in reaching the goals of Section 3025 of reducing readmission rate, CMS spending, and improving quality of care. AHA’s proposed policy includes a readjusted metric which takes into consideration the socioeconomic and socio demographic factors which cause hospital readmissions. This in itself helps reduce health disparities, improves access and quality of care, and continues to reduce readmission rates. The AHA’s proposal is recommended as it helps Section 3025 and the ACA in re-aligning the goals of improving quality, access, and reducing costs.

None.

Author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

©2017 Puckett. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.