MOJ

eISSN: 2379-6383

Research Article Volume 2 Issue 1

1Research and development, County Council Vasternorrland, Sweden

2Department of Nursing Sciences, Mid Sweden University, Sweden

Correspondence: Niclas Olofsson, Department of Research and Development, Vasternorrland County Council, Sundsvall Hospital, Sweden, Tel +4661180078

Received: November 05, 2014 | Published: January 28, 2015

Citation: Olofsson N, Holmstrom MR, Kristiansen L. Assessing the construct validity and reliability of school health records of the ‘health dialogue questionnaire,’ in 7th grade in compulsory school. MOJ Public Health. 2015;2(1):9–18. DOI: 10.15406/mojph.2015.02.00010

Background: The aim for this study was to assess the construct validity and reliability of the Health Dialogue Questionnaire (HDQ), 7th grade in compulsory school through comparison of the HDQ, with Paediatric Quality Of Life Inventory (PedsQLTM), Local monitoring of youth policy questionnaire (LUPP®) and Health behaviour in Swedish school-aged children (HBSC).

Design and methods: A sample was created from HDQ (n= 2008), PedsQLTM (n=477), LUPP (n=2648), HBSC, (n=1500) andan exploratory factor analysis was performed in order to evaluate the construct validity of HDQ of the school children´s health in school settings.

Results: The results supported the HDQ as a valid 24 items factorial model, for girls a five factorial model and for boys a four factorial model for school children aged 13years old (grade 7). The girls’ model explained 63 % of the variance, while the boys’ model explained 58 % of the variance. A majority of the questions showed an agreeable concurrent and discriminant validity.

Conclusions: The HDQ questionnaire is a valid instrument for measuring 13-year-old school children’s self-reported-health.

Keywords: adolescents, construct validity, factor analysis, health dialogue questionnaire, health promotion

HDQ, health dialogue questionnaire; PedsQLTM, paediatric quality of life inventory; LUPP®, local monitoring of youth policy questionnaire; HBSC, health behaviour in Swedish school-aged children; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation; TLI, tucker-lewis index; CFI, comparative-fit-index; GFI, goodness-of-fit index; ITC, item-total-correlation; M, mean value; SD, standard deviation; SMC, squared multiple correlation

In a WHO study including 40 countries, Sweden was identified as one of the countries where the majority of children live healthy and safe lives, eat healthy foods regularly, are physically active and play and go to school in a safe environment.1 Schoolchildren’s Health in Sweden has improved for many years, with increasing life expectancy and decreasing health problems. This increased health can be linked to increased financial resources, enhanced level of education and better health care and knowledge of how to promote health and prevent illness.2 Children’s health is a broad concept, incorporating much more than a simplistic freedom from medical illness. In this study the World Health Organizations3 definition is used. Time trends from 1985/86 to 2005/06 among Swedish boys and girls; show that the risk of mental health problems such as nervousness, feeling low and sleeping difficulties has increased steadily.1,4,5 Childhood health and development is affected by the environment and the child’s genetic heritage, but first and foremost by the family, living conditions, lifestyles, school and friends.6

Thirteen year olds

School-children in 7th grade are in the middle of the greatest development process in their life; puberty. There is a major puberty gender difference, in that girls are approximately two years ahead of boys. Both genders develop their sexuality and they go through a great cognitive ability development. They are striving to answer important questions: ‘Who am I?’ and ‘What will become of me?’. During this period of time there is also an increasing workload with homework and higher academic demands from school. The social activities often include sports clubs etc. and a closer friendship within and across gender often develop. Parallel to this the school environment changes in different ways, for instance, with larger school units. All together this period of time is very demanding period for most teens.7–9

The health dialogue questionnaire(HDQ)

The HDQ has been tested for 10-y-olds in grade 4and proved to be reasonably valid.10The HDQ specific for the 13-y olds in 7th grade is not yet tested for validity and reliability.

Aim

The aim was to assess the construct validity and reliability of the HDQ 7th grade in compulsory school through comparison of the HDQ with Paediatric Quality Of Life Inventory (PedsQLTM), Local monitoring of youth policy questionnaire (LUPP®) and Health behaviour in Swedish school-aged children (HBSC).

Research context

The data originate from the school nurses HDQ in 7th in compulsory school in the county of Vasternorrland. Each year registers about 8,000health consultations in the county. The county contains of seven municipals, and the region is characterized by large rural areas and few cities approximately 250,000 inhabitants located in the middle/north of Sweden. Furthermore the county has lower middle income, education level and proportion of residents with foreign background compared with the national average. The county’s school students have slightly lower average level of grades compared with the national average.11

Sample

The validity and reliability calculation were investigated based on the data from the HDQ in 7th grade in compulsory school (n= 2008), the HBSC questionnaires (n=1500), the “LUPP®”questionnaires (n=2648) and the PedsQLTM (n=477), in the academic year 2009/2010. The sample size for HDQ corresponded to 77 % girls and 79 % boys of all 7thgrades school girls and boys in the county.11

Data collected

The text regarding the used instruments was presented as follows:

The health dialogue questionnaire, the HDQ: The County Council and the seven municipalities reached consensus on a systematically structured approach to the collection of school children’s health data. The HD represents a cross-sectional image of the child’s SRH regarding physical, mental and social health. The HDQ was offered to all school children at four occasions: in preschool, in fourth grade, in seventh grade, the first year of high school, and follows the child’s development and growth from 6 to 16years old and therefore repeat the content with age appropriate questions.12–14 The HDQ consisted of a structured questionnaire covering three dimensions of health physical, mental and social. The physical dimension included six questions/items. The mental dimension included five questions/items, while, the third dimension was social and included four questions/items. The school nurses who conduct the HDQ was situated at the school and shared the school environment with the school children at a daily base and were responsible for the data collection at each separate school i.e. distribution of written as well as oral information to all children and parents regarding voluntary participation and the registration of each HDQ. The school nurses were also responsible for the individual feedback to the students.

Health behavior in Swedish school-aged children (HBSC): The HBSC was a part of the WHO global survey and since 1985/1986 this study has taken place around the world every four years, most recently in over 40 different countries. The international standard questionnaire enables the collection of common data across participating countries and thus enabled the quantification of patterns of key health behaviours, health indicators and contextual variables. School children aged 11, 13 and 15 were asked to answer different health questions during their ordinary school classes and give a cross-sectional image of school children’s health.15 The HBSC consisted of a structured questionnaire with 82 questions covering four dimensions of health behaviour among school aged children. The dimensions were ‘Self-rated health and general well-being’, ‘Lifestyle’, ‘Social relationships’ and ‘School’.

The sampling method for participating school children was carried out in a two-step cluster design. First, a national representative cluster of schools was randomly selected. Second, a selection of schools or classes in each grade was included in the study, with at least 1500 school children in each grade; data consisted of school children 13years old from the academic year 2009/2010. The cluster of schools differs for each occasion the HBSC is conducted. Furthermore the HBSC was a school-based survey with data collected through self-completion questionnaires administered in the classroom by teachers. The HBSC did not include individual contact, dialogue or feedback concerning the questionnaires with the school children. The teacher is responsible for distribution of information concerning the study, such as parental agreement and school children´s voluntary participation.

Pediatric quality of life inventory (PedsQLTM): The PedsQLTM was a modular approach to measuring health-related quality of life in children and adolescents. The PedsQLTM consisted of brief, practical, generic core scales suitable for use with healthy school and community populations. Accordingly, the PedsQLTM consisted of developmentally appropriate forms for children ages 2-4, 5-7, 8-12 and 13-18years. Paediatric self-report was measured in children and adolescents ages 5-18years. The PedsQLTM was not used on a regular base in school environment, but mostly used in the research context.16 The PedsQLTM encompassed the essential core domains for paediatric health related quality of life measurement:

The questionnaires were distributed by the school nurses in one of the municipalities in the county, in addition to the HDQ to the same individuals.

Knowledge about young people-LUPP®: The LUPP® (a local follow-up of youth policy) was a cross-sectional survey that enabled municipalities to gather knowledge on the living situation of young people, as well as information on their experiences and opinions, since 2001. The Swedish Agency for Youth and Civil Society has developed the LUPP® survey in consultation with municipal representatives and researchers. The survey was adapted for different age groups: young people at compulsory school aged 13-15; young people at upper secondary school aged 16-18; and young adults 19-25years old. The LUPP® survey contains approximately 80 questions was divided into different modules with questions concerning the perception of influence and democracy, wellbeing school, leisure activities, work, health and future plans. The survey was mainly intended to be conducted electronically in school. In order to reach young people outside school it could be supplemented with a mail survey, in either electronic or paper form.

The LUPP® survey could be carried out electronically or on paper, by the latter age group, a web-based survey, while the younger age group typically use questionnaires implemented during a lesson hours in school by teachers. Distribution was like the HBSC. LUPP® survey was analysed and reported at a municipal and national level and used in the research context.

Statistical analyses

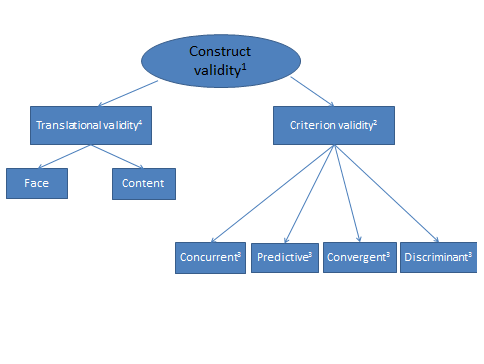

Assessing the usefulness of school health records demands a structured approach to validity. A schematic picture of the construct validity1 model was used as the analysing structure could be seen in Figure 1. A variety of ways exists to evaluate the construct validity and in general the order of analysis follows chronologically 1 to 3 (Figure 1). Construct validity consisted of Translational validity4, though in the model not analysed and henceforward not mentioned, while Criterion validity2 consisted of concurrent3 (Table 1), predictive3, convergent3 and/or discriminant3 (Table 2) validity.

Related items defined a part of a construct and were grouped and modelled together as a factor/s or a latent construct/s. A structural equation model approach was used to develop and test the factor models. In the first structure analyses models, all the items were modelled as indicators of the intended underlying latent constructs. A two-step structural equation model procedure was applied. In the first step, an exploratory factor analysis was conducted to determine a model where the constructs measured the underlying latent variables. The factor analysis assumed each manifest variable/item to be a distinct indicator of an underlying latent construct, whereby different constructs were permitted to be inter correlated. In the second step a Mann Whitney U test was carried out to determine if the latent variables were acceptable as independent constructs that could be sufficiently distinguished from each other. Significant Mann-Whitney test values indicate discriminate validity. The appropriateness of a specific factor analysis model was assessed by measures of global and local fit. Global fit indicated whether the empirical associations among the manifest variables were appropriately reproduced by the model. For a variety of these global fit measures, certain criteria have to be met in order to accept the model under study as plausible and parsimonious. For the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), the model can be classified as good if the RMSEA is <= 0.05, and is acceptable if it is <=0.08. Furthermore, measures of incremental fit were used namely the comparative-fit-index (CFI) and the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI). A rule of thumb for incremental fit measures is that values >=0.97 are indicative of good fit, while values >=0.95 may be interpreted as acceptable. The goodness-of-fit index (GFI) is the measure of the relative amount of variance in the sample that was explained by the model. The index range from zero to one, and values close to one represented good fit. Measures of local fit evaluated whether each construct can be reliably estimated from its indicators and whether the constructs within the model are sufficiently distinguishable. The item-total-correlation (ITC) was a correlation between the question and the overall assessment, and in this cases the manifest items and their latent variables. Values for an item-total correlation between 0 and 0.19 may indicate that the question was not discriminating well, values between 0.2 and 0.39 indicate good discrimination and values 0.4 and above indicate very good discrimination.18–20

Ethics

This study followed the ethical principles recommended by the Research Council and was approved by the Ethics Committee at the Medical Faculty, Umea University, to be evaluated the (Dnr 2008-122M).

The HDQ was salutogenic and the percentages of positive answers are presented in Table 1. Measuring the concurrent validity are done by comparing the percentages emanating from the HDQ with similar questions from different but resembling questionnaires HBSC, PedsQLTM and LUPP®. Describing and analysing the percentages in Table 1, the percentages were averagely underestimated 9 percentages (Table 1); the items “daily physical activity”, “eating breakfast every school day”, and “sleep” differ mostly between HDQ and the population proxies.

13-14 years |

HDQ |

HBSC |

PedsQLTM |

LUPP® |

||||

Girl |

Boy |

Girl |

Boy |

Girl |

Boy |

Girl |

Boy |

|

Always concentrate |

75 |

71 |

76 |

73 |

||||

Not bullied |

90 |

92 |

87 |

87 |

94 |

95 |

78 |

91 |

Feeling pressured by schoolwork sometimes or less |

87 |

90 |

81 |

87 |

88 |

87 |

33 |

62 |

Rather good or better school satisfaction |

89 |

90 |

89 |

96 |

||||

Eating breakfast every school day |

74 |

81 |

68 |

76 |

56 |

67 |

||

Drinking soft drinks once a week or less |

18 |

15 |

11 |

12 |

||||

Daily physical activity |

24 |

32 |

4 |

8 |

15 |

11 |

||

Less than 1 hour TV a day |

42 |

37 |

32 |

34 |

||||

Less than 1 hour computer a day |

42 |

37 |

42 |

54 |

||||

Rather good or better self-reported health |

90 |

96 |

98 |

99 |

70 |

81 |

||

Headache |

58 |

77 |

59 |

74 |

54 |

54 |

||

Stomach ache |

67 |

84 |

70 |

83 |

66 |

87 |

||

Back/neck/shoulder ache |

69 |

77 |

79 |

84 |

71 |

87 |

||

Feeling low/sad |

70 |

92 |

57 |

70 |

76 |

92 |

||

Nervousness |

86 |

95 |

60 |

80 |

85 |

97 |

||

Irritable/bad tempered |

53 |

68 |

37 |

49 |

78 |

87 |

||

Someoneto talk with |

96 |

97 |

||||||

Sleep |

86 |

88 |

36 |

44 |

85 |

87 |

50 |

62 |

Never tried smoking |

90 |

91 |

78 |

76 |

86 |

89 |

||

Never tried snuff |

96 |

94 |

94 |

84 |

95 |

92 |

||

Never tried alcohol |

88 |

85 |

82 |

85 |

||||

Table 1 Percentages of positive answers from the 7th grade HDQ and their population proxy scores (n=2008). Only HDQ items with comparable proxies are shown (Concurrent validity)3

Items in HDQ exploratory factor analysis models with insufficient model compatibility were sequentially eliminated from the model until criteria for good model fit were reached. The resulting models each comprised of 24 items and exhibited an all in all acceptable fits (Tables 3 & 4), acceptable fit threshold (actual model fit index value) χ2/df <3 (2.86); RMSEA<=0.08 (0.031); CFI>=0.95 (0.926); TLI>=0.95 (0.914); GFI >=0.90 (0.94). RMSEA even reached the good fit threshold (<=0.05) while the CFI and TLI levels just reached suggested less restrictive fit thresholds (>=0.90).18,19

Environment |

Psychology |

Behaviour |

Work |

Physical_Girls |

Physical_Boys |

Peds QL Psychological |

Peds QL Physical |

|

PedS QL Total score girls |

-.33 (4132) |

-.68 (3856) |

-.31 (1196) |

-.55 (351) |

-.58 (1422) |

.96 (1100) |

.80 (793) |

|

Environment |

0.42 |

.10 (n.s.) |

0.33 |

0.36 |

-0.35 |

-0.19 |

||

Psychological |

0.38 |

0.54 |

0.64 |

-0.72 |

-0.4 |

|||

Behaviour |

0.26 |

0.31 |

-0.31 |

-0.22 |

||||

Work |

0.44 |

-0.59 |

-0.33 |

|||||

Physicalgirls |

-0.56 |

-0.46 |

||||||

Peds QL psychological |

0.6 |

|||||||

PedS QL Total score boys |

-.31 (3430) |

-.66 (3174) |

.-05 (n.s.) (1180 (n.s.)) |

-.68 (548) |

.97 (435) |

.86 (237) |

||

Environment |

0.51 |

.01 (n.s.) |

0.42 |

-.34 |

-0.2 |

|||

Psychological |

.11 (n.s.) |

0.62 |

-.68 |

-0.49 |

||||

Behavior |

0.19 |

-.06 (n.s.) |

-.00 (n.s.) |

|||||

Physical boys |

-0.68 |

-0.54 |

||||||

Peds QL psychological |

0.71 |

Table 2 Bivariate correlations and results of the convergence and discriminant validity test (in parenthesis: Mann Whitney U-values) of the scales from the exploratory factor analysis (Figure 1 & 3). All results significant with P<.001 otherwise stated as (n.s.)

In the girl’s model (Figure 2), items 1 (psych 1) and item 2 (psych 2) showed content overlap. Item 4 (psych 4) and item 6 (psych 6) also appeared to overlap as well as item 1 (psych 1) and item 5 (psych 5). Each manifest item was mutually correlated >0.50. Error covariance parameters were included in the model to manage the item content overlaps in the girl model. In the boy’s model (Figure 3), items 1 (psych1) and item 2 (psych 2) also showed content overlap. Item 16 (phys 7), item 19 (phys 9) and item 13 (phys 1) and item 15 (phys 4) correlated >0.40. Alas to modify the model, error covariance parameters were added in the boy model. Turning to the unstandardized model estimates, all were significant in both models as could be seen in Table 3 & 4. In the girls model the standardized parameter estimates were generally high (lowest psych 4-0.31 vs. highest behave 1 0.90) as well as in the boy model (lowest psych 3 0.18 vs. highest behav 2 0.84) (Table 3 & 4).

Items |

Item labels |

Unstandardized |

Standardized |

P |

||

Feeling low/sad |

Sad |

<--- |

Psychology |

1 |

0.722 |

|

Nervousness/afraid |

Afraid |

<--- |

Psychology |

.734 (.038) |

0.615 |

*** |

Someoneto talk with |

Talk |

<--- |

Psychology |

.108 (.011) |

0.364 |

*** |

Not bullied |

Bully |

<--- |

Psychology |

-.146 (.017) |

-0.313 |

*** |

Rather good or better self-reported health |

SRH |

<--- |

Psychology |

.810 (.037) |

0.764 |

*** |

Rather good or better school satisfaction |

Satisfy |

<--- |

Psychology |

.662 (.040) |

0.63 |

*** |

School yard |

S-yard |

<--- |

Environment |

1 |

0.523 |

|

Showers |

Shower |

<--- |

Environment |

1.253 (.107) |

0.543 |

*** |

Canteen |

Canteen |

<--- |

Environment |

1.027 (.086) |

0.565 |

*** |

Classrooms |

Classroom |

<--- |

Environment |

1.148 (.087) |

0.692 |

*** |

Sporthall |

Sport hall |

<--- |

Environment |

.966 (.087) |

0.505 |

*** |

Restroom |

Restroom |

<--- |

Environment |

1.029 (.101) |

0.446 |

*** |

Headache |

Head |

<--- |

Physical |

1 |

0.631 |

|

Stomacheache |

Stomach |

<--- |

Physical |

.840 (.058) |

0.58 |

*** |

Back/neck/shoulderache |

Ache |

<--- |

Physical |

.869 (.066) |

0.52 |

*** |

Painkillers |

Pharm |

<--- |

Physical |

.643 (.049) |

0.51 |

*** |

Irritable/bad tempered |

Angry |

<--- |

Physical |

.984(.062) |

0.653 |

*** |

Sleep |

Sleep |

<--- |

Physical |

.747 (.051) |

0.596 |

*** |

Never tried smoking |

Smoking |

<--- |

Behavioral |

1 |

0.905 |

|

Never triedsnuff |

Snuff |

<--- |

Behavioral |

.410 (.024) |

0.686 |

*** |

Never triedalcohol |

Alcohol |

<--- |

Behavioral |

.576 (.039) |

0.551 |

*** |

Always concentrate |

Conc |

<--- |

Work |

1 |

0.782 |

|

Feeling pressured by schoolwork sometimes or less |

Quiet |

<--- |

Work |

.752 (.057) |

0.491 |

*** |

Quiet in the classroom |

Stress |

<--- |

Work |

.920 (.051) |

0.733 |

*** |

Table 3 Unstandardized, Standardized and Significance Levels for Model in Figure 1 (girls) (Standard Errors in Parentheses; n = 942) Χ1 (476)=1362; p<0.001; Χ2/df=2.9; RMSEA=.031; CFI=.926; TLI=.914; GFI=.94

Items |

Item labels |

Unstandardized |

Standardized |

P |

||

Feeling low/sad |

Sad |

ß- |

Psychology |

1 |

0.636 |

|

Nervousness/afraid |

Afraid |

ß- |

Psychology |

.738 (.042) |

0.545 |

*** |

Someoneto talk with |

Talk |

ß- |

Psychology |

.060 (.012) |

0.179 |

*** |

Not bullied |

Bully |

ß- |

Psychology |

-.216 (.025) |

-0.335 |

*** |

Rather good or better self-reported health |

SRH |

ß- |

Psychology |

.974 (.060) |

0.725 |

*** |

Rather good or better school satisfaction |

Satisfy |

ß- |

Psychology |

.876 (.063) |

0.574 |

*** |

School yard |

S-yard |

<--- |

Environment |

1 |

0.599 |

|

Showers |

Shower |

<--- |

Environment |

1.110 (.085) |

0.579 |

*** |

Canteen |

Canteen |

<--- |

Environment |

.837 (.067) |

0.545 |

*** |

Classrooms |

Classroom |

<--- |

Environment |

.754 (.057) |

0.598 |

*** |

Sporthall |

Sport hall |

<--- |

Environment |

.777 (.069) |

0.473 |

*** |

Restroom |

Restroom |

<--- |

Environment |

1.019 (.082) |

0.537 |

*** |

Headache |

Head |

<--- |

Physical |

1 |

0.539 |

|

Stomacheache |

Stomach |

<--- |

Physical |

.912 (.076) |

0.52 |

*** |

Back/neck/shoulderache |

Ache |

<--- |

Physical |

1.042 (.089) |

0.503 |

*** |

Painkillers |

Pharm |

<--- |

Physical |

.549 (.054) |

0.34 |

*** |

Irritable/bad tempered |

Angry |

<--- |

Physical |

1.181 (.089) |

0.611 |

*** |

Sleep |

Sleep |

<--- |

Physical |

.853 (.069) |

0.549 |

*** |

Feeling pressured by schoolwork sometimes or less |

Stress |

<--- |

Physical |

.922 (.078) |

0.514 |

*** |

Quiet in the classroom |

Quiet |

<--- |

Physical |

.580 (.057) |

0.424 |

*** |

Always concentrate |

Conc |

<--- |

Physical |

.659 (.057) |

0.492 |

*** |

Never tried smoking |

Smoking |

<--- |

Behavioral |

1 |

0.821 |

|

Never triedsnuff |

Snuff |

<--- |

Behavioral |

.911(.059) |

0.835 |

*** |

Never triedalcohol |

Alcohol |

<--- |

Behavioral |

.589 (.049) |

0.439 |

*** |

Table 4 Unstandardized, Standardized and Significance Levels for Model in Figure 3 (boys) (Standard Errors in Parentheses; n = 951) Χ2 (476)=1362; p<0.001; Χ2/df=2.9; RMSEA=.031; CFI=.926; TLI=.914; GFI=.94

The item total correlations between the manifest item and their latent variable (factor) were generally high for both girls and boys. One item (psych 3) though, in the boy model only managed to reach 0.14 (Table 5). All the other values, at least indicated good discrimination (0.2>=ITC<=0.39), with a majority of the values (90%) 0.4 and above indicating a very good discrimination (Tables 5 & 6).18,19 Furthermore, indices of local-fit proved that each latent construct was agreeably reliably measured by its indicators/items 0.42 % of the manifest items in the girl model and 17% in the boy model was measured acceptably by its underlying construct (indicator reliability, >=0.40) (SMC R2in Tables 5 & 6).18,19

Items |

Item labels |

ITC |

M |

SD |

SMC (R2) |

Scale dimension |

Cronbach’s alpha |

Feeling low/sad |

Sad |

,59 |

4,52 |

,76 |

0.4 |

||

Nervousness/afraid |

Afraid |

,50 |

4,69 |

,65 |

0.3 |

||

Someoneto talk with |

Talk |

,14 |

,97 |

,16 |

0.03 |

||

Not bullied |

Bully |

-,34 |

,11 |

,31 |

0.11 |

||

Rather good or better self-reported health |

SRH |

,54 |

4,54 |

,64 |

0.53 |

||

Rather good or better school satisfaction |

Satisfy |

,39 |

4,21 |

,73 |

0.33 |

Psychology |

0.6 |

School yard |

S-yard |

,50 |

3,71 |

,85 |

0.36 |

||

Sporthall |

Sporthall |

,45 |

4,19 |

,83 |

0.22 |

||

Showers |

Shower |

,47 |

3,52 |

,97 |

0.34 |

||

Canteen |

Canteen |

,40 |

3,93 |

,78 |

0.3 |

||

Classrooms |

Classroom |

,49 |

3,93 |

,64 |

0.36 |

||

Restroom |

Restroom |

,44 |

3,11 |

,96 |

0.24 |

Environment |

0.72 |

Headache |

Head |

,58 |

4,16 |

,90 |

0.29 |

||

Stomacheache |

Stomach |

,53 |

4,35 |

,85 |

0.27 |

||

Back/neck/shoulderache |

Ache |

,45 |

4,16 |

1,00 |

0.25 |

||

Painkillers |

Pharm |

,47 |

4,13 |

,78 |

0.12 |

||

Irritable/bad tempered |

Angry |

,51 |

3,92 |

,94 |

0.37 |

||

Sleep |

Sleep |

,45 |

4,27 |

,75 |

|||

Feeling pressured by schoolwork sometimes or less |

Stress |

,65 |

3,54 |

,87 |

0.26 |

||

Quiet in the classroom |

Quiet |

,57 |

3,74 |

,66 |

0.18 |

||

Always concentrate |

Conc |

,49 |

3,83 |

,65 |

0.29 |

Physical |

0.76 |

Never tried smoking |

Smoking |

,60 |

3,73 |

,72 |

0.68 |

||

Never triedsnuff |

Snuff |

,63 |

3,88 |

,74 |

0.7 |

||

Never triedalcohol |

Alcohol |

,39 |

3,44 |

,88 |

0.19 |

Behavioral |

0.71 |

Table 5 Overview of the scales and items of the confirmatory factor analysis model (boys) ITC, item-total-correlation; M, mean value; SD, standard deviation; SMC, squared multiple correlation

Items |

Item labels |

ITC |

M |

SD |

SMC (R2) |

Scale dimension |

Cronbach’s alpha |

Feeling low/sad |

Sad |

,69 |

4,08 |

,95 |

0.52 |

||

Nervousness/afraid |

Afraid |

,58 |

4,43 |

,81 |

0.38 |

||

Someoneto talk with |

Talk |

,31 |

,96 |

,20 |

0.13 |

||

Not bullied |

Bully |

-,32 |

,11 |

,32 |

0.1 |

||

Rather good or better self-reported health |

SRH |

,66 |

4,43 |

,72 |

0.58 |

||

Rather good or better school satisfaction |

Satisfy |

,48 |

4,32 |

,71 |

0.4 |

Psychology |

0.69 |

School yard |

S-yard |

,46 |

3,8 |

,75 |

0.27 |

||

Sporthall |

Sport hall |

,41 |

4,20 |

,75 |

0.26 |

||

Showers |

Shower |

,49 |

3,53 |

,90 |

0.3 |

||

Canteen |

Canteen |

,46 |

4,04 |

,71 |

0.32 |

||

Classroom |

Classroom |

,53 |

4,00 |

,65 |

0.48 |

||

Restroom |

Restroom |

,39 |

3,31 |

,90 |

0.2 |

Environment |

0.72 |

Headache |

Head |

,58 |

3,81 |

1,02 |

0.4 |

||

Stomacheache |

Stomach |

,53 |

3,99 |

,93 |

0.34 |

||

Back/neck/shoulderache |

Ache |

,45 |

4,02 |

1,08 |

0.27 |

||

Painkillers |

Pharm |

,47 |

3,73 |

,81 |

0.26 |

||

Irritable/bad tempered |

Angry |

,51 |

3,64 |

,97 |

0.43 |

||

Sleep |

Sleep |

,45 |

4,18 |

,81 |

0.36 |

Physical |

0.76 |

Never tried smoking |

Smoking |

,65 |

4,90 |

,40 |

0.82 |

||

Never triedsnuff |

Snuff |

,57 |

4,97 |

,22 |

0.47 |

||

Never triedalcohol |

Alcohol |

,49 |

4,88 |

,38 |

0.3 |

Behavioral |

0.71 |

Quiet in the classroom |

Quiet |

,52 |

3,73 |

,72 |

0.54 |

||

Always concentrate |

Conc |

,58 |

3,88 |

,74 |

0.61 |

||

Feeling pressured by schoolwork sometimes or less |

Stress |

,36 |

3,44 |

,88 |

0.24 |

Work |

0.67 |

Table 6 Overview of the scales and items of the confirmatory factor analysis model (girls) ITC, item-total-correlation; M, mean value; SD, standard deviation; SMC, squared multiple correlation

A confirmatory factor analysis confirmed a five factor model for the girls and a four factor model for the boys in school (7th grade) using the items from HDQ (construct validity). The analyses resulted in two finals Table structures (girls and boys) that were tested and confirmed on another HDQ seven graders sample (academic year 2010/2011, n=1979). The five factor girl’s model resulted in a 63% cumulative variance explained and the four factor boy’s model in 58% cumulative variance explained (principal axis factoring with varimax rotation). In Table 2, the bivariate correlations of all scales from the exploratory factor analyses models (Figures 2 & 3) and the results of the convergent and discriminant validity test is shown. The tests were done on a new sample of seven graders from another year (academic year 2010/2011, n=1979) to test stability of the scales. The internal consistency measured by Cronbach’s alpha, were generally high (behaviour 0.47 girls and 0.75 boys; environment 0.76 girls and 0.79 boys; psychology 0.78 girls and 0.67 boys; work 0.82 girls; physical 0.74 girls and 0.73 boys).

The aim was to psychometrically test HDQ for measuring the self-reported health in 7thgraders in compulsory school. The major finding was that it was possible to adequately model five (girls) respectively four (boys) hypothetical dimensions of the health In girls health these were psychological, environmental, physical, behavioral, and working environment (work) and the four hypothetical dimensions in boys health were psychological, environmental, physical and behavioral (Figures 2 & 3). A confirmatory factor analysis confirmed that it was possible to adequately model girls and boys health (construct validity) in 7th grade using the items from HDQ. The analyses resulted in two finals Table structures (girls and boys) that were tested and confirmed on another HDQ seven graders sample (academic year 2010/2011, n=1979). The five factor girl’s model resulted in 63% cumulative variance explained and the four factor boy’s model in 58% cumulative variance explained (principal axis factoring with varimax rotation). The concurrent criterion related validity was analysed when the HDQ was compared with answers from three other questionnaires similar questions and similar sample (for HDQ and PedsQLTM actually identical). Ambiguous questions showed less criterion related validity, but most of the questions in the HDQ related highly with their proxy counterparts.

Convergent and discriminant validity was examined using the newly produced scales from the structural equation modelling factor analysis and correlating the scales resulted in understandable and expected associations. To further strengthen the validity of the HDQ would be to test the questionnaire in a highly different sample. The fact that we analyzed a regional cohort composed of mostly white children, living predominantly rural, with low or middle class parents mean that the population was well-defined. The questionnaire results might not be generalizable, for instance, to a more heterogenic urban area.

Methodological consideration

Since all results were assessed using self-reports, results may have been biased by common method variance. The common method variance may state a real bias in survey-type of studies and enhance the observed correlation between variables.21 Despite the above mentioned, the overall findings suggests that structured validation studies helps developing sound and usable questionnaires.

Children “learn health” through role models (mainly parents but also other adults close to the children).22 Therefore, the school is an important arena for health promotion, as all children attend school and all adults within a school have an opportunity to serve as role models.23,24 A health promoting school strengthens children’s self-esteem and school performance25 and learning and health are known to be generated by the same factors.26,27 The questionnaire may be used in health promoting practices in school, serving as a feedback instrument for assessing the health of school children in 7th grade.

The authors would like to acknowledge all the school children and school nurses.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

©2015 Olofsson, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.