MOJ

eISSN: 2381-179X

Case Report Volume 12 Issue 3

Service de Réanimation P33, CHU Ibn Rochd de Casablanca, Morocco

Correspondence: Maghrabi O, Service de Réanimation P33, CHU Ibn Rochd de Casablanca, 17 rue amyot Appt 18, Casablanca, Morocco, Tel +212616202715

Received: October 13, 2022 | Published: October 21, 2022

Citation: Hafiani Y, Maghrabi O, Lakrafi A, et al. Thyrotoxicosis complicating a COVID-19 infection. MOJ Clin Med Case Rep. 2022;12(3):38-39. DOI: 10.15406/mojcr.2022.12.00416

The SARS-COV-2 infection, in the typical case, results in acute forms of pneumonia, the severe forms of which can be life-threatening. However, it can also cause various extra-pulmonary attacks (cutaneous, neurological, cardiovascular, ophthalmological, etc.) but also endocrine (pancreatic, pituitary, etc.), and in particular thyroid disorders associated with COVID-19. In this case report, we display the unusual case of a thyrotoxicosis due to the COVID-19 in a woman of 57 years of age with a severe pneumonia, which appeared on the ninth day of her infection. The thyrotoxicosis was suspected in front of a sudden tachycardia with no apparent cause, associated with a swollen neck. The diagnosis is confirmed by an elevation of thyroid enzymes T4 and T3, with a thyroid ultrasound revealing multiple hypoechoic area. The patient was treated with steroids and the symptoms have gradually lessened. In conclusion, subacute thyroiditis secondary to SARS-COV-2 infection is a hitherto poorly described complication that may go unnoticed because of its delayed onset. A clinical examination for signs of thyrotoxicosis and pain in the anterior neck region is usually sufficient to evoke this diagnosis. Thyroid hormone assay may be useful to confirm and treat this entity.

Keywords: COVID-19, thyrotoxicosis, subacute thyroiditis, steroids, tachycardia, fever

COVID-19, corona virus disease; FT4, free thyroxin; FT3, free triodothyronine; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; CRP, C-reactive protein; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine transaminase; TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone; IL6, interleukin-6

The COVID-19, caused by the coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is the infection resulting in severe acute respiratory distress syndrome that has spread rapidly since December last year and led the World Health Organization to announce the COVID-19 epidemic as a pandemic on March 11, 2020.1 This SARS-COV-2 infection, in the typical case, results in acute forms of pneumonia, the severe forms of which can be life-threatening. However, recent clinical and epidemiological data report various extra-pulmonary attacks (cutaneous, neurological, cardiovascular, ophthalmological, etc.) but also endocrine (pancreatic, pituitary, etc.), and in particular thyroid disorders associated with COVID-19.2 Several studies report the correlation between SARS-COV-2 infection and thyroid hormone depletion.3-5 Certainly, the association between COVID-19 and Thyrotoxicosis is still poorly elucidated in the literature. Thyrotoxicosis is the constellation of clinical signs that occur when peripheral tissues are exposed and respond to excess thyroid hormone: FT4 and FT3.6

On November 22, 2020, a 57-year-old woman presented a dry cough and respiratory discomfort with a reported fever of 38.2C, which motivated her to undergo a nasal swab PCR that came back positive on March 26, 2022.

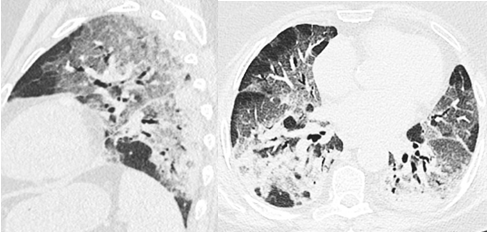

A thoracic CT scan performed on March 29, 2022 revealed ground glass lesions reaching 40% of the lung parenchyma (Figure 1). In view of these lesions and the worsening respiratory distress, the patient was referred to us on March 30, 2022 for specialized management of her SARS-COV-2 respiratory infection. On admission, the patient presented with respiratory distress, asthenia, and a fever of 38.4ºC. However, the patient did not report any significant pathological history.

Figure 1 Axial (right) and sagittal (left) sections in the parenchymal window without contrast injection, showing bilateral asymmetric ground-glass areas, mainly subpleural, some of which are crazy paving associated with localized condensation and bronchiectasis.

Clinically, the patient was conscious with a Glasgow score of 15/15, hemodynamically stable with an estimated heart rate of 74bpm, blood pressure of 120/70 and pulse saturation of 77% on 15L of oxygen on a high concentration mask.

The complete clinical examination did not reveal any particularities except for signs of respiratory struggles such as intercostal pulling and slight crackling of the lungs predominantly on the pulmonary bases. The examination of the ears, nose and throat did not reveal any pain or swelling related to the thyroid gland. Her biological workup showed an elevated CRP (140mg/L), mild hepatic cytolysis (AST/ALT=84/79), lymphopenia (740) and an elevated IL6 level (51.6).

A specific treatment of COVID-19 was started on the day of her admission, consisting of oxygen therapy with Optiflow (30L/min + FIO2=100%), azithromycin, corticosteroid therapy (Dexamethasone 6mg/d) and a vitamin intake.Her evolution is marked by an improvement of her respiratory symptoms, a progressive decrease of her oxygen needs and a lowering of her fever.

However, on April 3, 2022, at the fifth day of her treatment, the patient reported asthenia, palpitations, pain in the anterior part of the neck and a reappearance of a fever plateau at 38.7ºC. A thorough clinical examination revealed tachycardia at 97bpm, marked pain on palpation of a swollen thyroid. There were no respiratory symptoms; pulse saturation was 93% under 10L/min of O2. Biologically, there was an elevated FT4 and FT3 level (29.2nmol/l and 9.1pmol/l respectively), a collapsed TSH level lower than 0.05mIU/l and a hyperleukocytosis at 11200. Thyroid ultrasound revealed multiple hypoechoic areas. The diagnosis of subacute thyroiditis was therefore retained.

We did not need to change the therapy; the patient was already on steroids for the pneumonia. The symptomatology of subacute thyroiditis had gradually regressed 3 days after its onset. There was still a slight pain on palpation of a still swollen thyroid. On April 12, 2022, the patient was declared discharged after clinico-biological improvement and a complete weaning from oxygen therapy.

The term "thyroiditis" describes inflammatory changes of the thyroid gland, which can be induced by different pathologies. Among these pathologies, subacute granulomatous thyroiditis is noteworthy. Since the majority of patients report a viral infection of the upper respiratory tract about 2-8 weeks before the occurrence of this form of thyroiditis, it is accepted that it is triggered by a viral infection or a post-viral inflammatory process.7,8

In the case of SARS-COV-2 infection, several mechanisms can cause damage to the thyroid gland. Thyroiditis may be due to the viral origin of the infection which causes destruction and thus inflammation of the thyroid gland. A significant number of patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS-CoV) have shown abnormalities in thyroid function. The follicular architecture of the gland was altered.9

ACE2 plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of coronavirus-induced lung injury as it is the host cell receptor from which the invasion occurs.10 More recent studies based on SARS-CoV-2 in 2020 showed that ACE2 expression levels were highest in the thyroid among other organs, such as small intestine, kidney, heart, and adipose tissue, providing insight into a plausible mechanism of thyroiditis pathophysiology in COVID-19.11,12

Thyroiditis may also be the consequence of the cytokine storm with elevated IL6 levels.2 This last hypothesis may explain the occurrence of Subacute Thyroiditis in our case, since the IL6 level was higher than 7 times normal.

Subacute thyroiditis is characterized by an episode of thyrotoxicosis that may last a few weeks, followed by hypothyroidism and finally a return to euthyroid conditions. Its diagnosis is based essentially on a set of clinical arguments. In the acute phase of the disease there is also an elevation of systemic markers of inflammation,13 which is difficult to judge in our case, given the largely inflammatory nature of the COVID-19 infection.

In our case, we notice the appearance of symptoms of subacute thyroiditis at day 12 of the beginning of the symptomatology of COVID-19, with no prior history of thyroid disfunction and an increase of the thyroid hormones and collapse of the TSH. All those combined reinforces the diagnosis of subacute thyroiditis and its viral origin SARS-COV-2.

The treatment is symptomatic and involves non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for pain. If there is no improvement after 2 to 3 days or if the initial pain is severe, prednisone (0.5 mg/kg/day) can be used. With corticosteroid therapy, a marked improvement in symptoms should occur after 1 to 2 days.14,15 Indeed, in our case, whom were already on corticosteroids for SARS-COV-2 infection, the symptoms related to subacute thyroiditis regressed rapidly after 3 days of their onset.

In conclusion, subacute thyroiditis secondary to SARS-COV-2 infection is a hitherto poorly described complication that may go unnoticed because of its delayed onset. A clinical examination for signs of thyrotoxicosis and pain in the anterior neck region is usually sufficient to evoke this diagnosis. Thyroid hormone assay may be useful to confirm and treat this entity.

None.

The authors report no conflict of interests.

©2022 Hafiani, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.