MOJ

eISSN: 2381-179X

Case Report Volume 7 issue 1

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Mohammed V University, Morocco

Correspondence: Salma Ouassour, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, National Center for Reproductive Health Ibn Sina, Mohammed V University, Morocco

Received: July 07, 2017 | Published: July 28, 2017

Citation: Ouassour S, Alami MH, Tazi Z, et al. Isolated fallopian tube torsion in pregnancy: an uncommon event. MOJ Clin Med Case Rep. 2017;7(1):186-188 DOI: 10.15406/mojcr.2017.07.00192

Isolated torsion of a fallopian tube in the third trimester of pregnancy is an uncommon event. Expedient diagnosis warrants a prompt management in view of better postoperative well-being for both mother and the fetus. Therefore, it can be challenging because the symptoms are relatively non specific. The ultrasound findings may be suggestive but the diagnosis is only made after the surgical exploration and histopathology.

We present a case of isolated tubal torsion in a primigravida occurring in the third trimester managed by laparotomic salpingectomy.

Keywords: fallopian tube torsion, acute abdomen, pregnancy, laparotomy

Isolated fallopian tube torsion is an uncommon cause of acute, lower abdominal pain in women of reproductive age and even more rare during pregnancy. The incidence is approximately one in one-and-a-half million females.1 The etiologies of torsion of the fallopian tube are unknown. The clinical characteristics and the imaging studies are not specific, diagnosis can be challenging and difficult which may delay managing this condition in a timely fashion. Laparotomy and laparoscopy are important tools in the diagnosis and prognosis of isolated torsion of a fallopian tube, and can help to preserve the fertility of this patients.2 We present a case of 30 weeks pregnancy with a right Fallopian tube torsion which was managed successfully in our institution by laparotomic salpingectomy.

A 23-year-old healthy primigravida was admitted to the Center of Reproductive Health atthe 30thweek of pregnancy with complaints of lower abdominal pain for 3days. The patient had no previous history of a similar pain or of any previous illness. The pregnancy had been uneventful until the occurrence of the pain which was constant, acute and situated in the right lower abdomen. The patient's vital signs were stable, and she was afebrile. Physical examination revealed tenderness in the right lower abdomen without palpable masses and a soft abdomen. The uterine fundal height corresponded to the period of gestation.

The ultrasound study revealed a single, life fetus, with a biometry compatible to a 30weeks pregnancy, with normal amniotic fluid volume and with a normal placenta with no signs of abruption. Kidneys and renal tract were normal. The appendix was also normal but we visualised a 60*30mm hypoechoic mass probably with a right adnexal origin. Color flow Doppler ultrasonography showed the circular vessels within this mass, presenting a whirlpool sign of twisted vascular pedicle. The left adnexa and ovaries were reported as normal. No free fluid was detected in the pouch of Douglas.

The laboratory blood parameters were normal with 11.7×103/L white blood cells (WBCs) and parameters for urine and liver function were also normal. The acute onset of pain, physical finding, and detection of an adnexal mass with whirlpool sign on ultrasonography raised suspicion of torsion of the right adnexal structures.

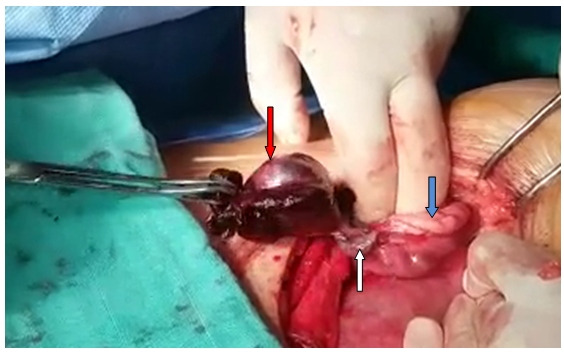

The patient was informed of the risk of maternal morbidity and mortality and of premature labour. Consented for an exploratory diagnostic and therapeutic surgery. So, we performed an urgent Pfannenstiel laparotomy (lack of laparoscopic equipment). On the right adnexa, the tube was dilated, twisted about its longitudinal axis and necrotic (Figure 1). Left tube, ovaries and the appendix were normal in appearance. The torted hydrosalpinx was detorted; however, the fallopian tube had been compromised because of the gangrenous aspect and it was necessary to proceed with removal. A right salpingectomy was performed. Intra operative period was covered with injection of terbutalin 0.5mg to prevent premature uterine contraction.

Figure 1 Per operative view. White arrow, the pedicle torsion of the right Fallopian tube; Blue arrow, normal right ovary; Red arrow, the gangrenous fallopian tube

The diagnosis of Fallopian tube torsion and hydrosalpinx was confirmed by the histopathological examination

The patient was discharged on the third day after surgery without any complains or surgical and obstetric complication. A control of fetal well-being was performed.

Fortunately, the pregnancy advanced smoothly with a regular follow-up, ending in aspontaneous vaginal delivery of a healthy, 2900g, female baby at the 39thweek of pregnancy. Postpartum recovery was unremarkable.

Isolated torsion of the fallopian tube is a rare but noteworthy cause of lower abdominal pain in women of reproductive age.3 Since 1933 only 25 cases of Fallopian tube torsion in pregnant women were described.4–6 The exact mechanisms that lead to torsion of the fallopian tube are not well understood. It occurs without ipsilateral ovarian involvement. It is associated with many conditions such as pregnancy, haemosalpinx, hydrosalpinx, ovarian or paraovarian cysts and other adnexal alteration or it can even occur with an otherwise normal fallopian tube.7

The risk of isolated tubal torsion increases in pregnancy. The right fallopian tube is commonly affected. This may be due to the presence of the sigmoid colon on the left side to slow venous drainage on the right side which may result in congestion.8,9

In our case, the underlying mechanism of tubal torsion was probably caused by a sequential mechanical event. This process begins with mechanical blockage of adnexal veins and lymphatic vessels by the pregnancy. This obstruction caused pelvic congestion and local edema which resulted in the enlargement of the adnexa, and induced partial or complete torsion.10

The most common presenting complaints of the Fallopian tube torsion is lower abdominal pain, generally with a sudden onset and accompanied by nausea, vomiting or urinary urgency.4,11 Physical findings include abdominal tenderness, with or without peritoneal signs and an in constant palpable mass.4,11 Laboratory findings are usually nonspecific. Necrosis can cause leukocytosis. The sedimentation rate or CRP can be elevated. Occasionally, the patient may have fever.11

The sonographic findings of isolated Fallopian tube torsion are not pathognomonic and are quite variable,3 especially in second and third trimesters of pregnancy, where the adnexas are more difficult to visualize. The most consistent finding on ultrasound is a midline cystic mass, associated with a normal ipsilateral ovary.4,12 Origoni et al.,4 suggest the use of Doppler flow ultrasound technique to make a differential diagnosis in case of total adnexal torsion. An isolated tubal torsion should be considered when a detailed Doppler flow ultrasound shows a normal ovary and a pelvic cyst.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is also reported as a valuable diagnostic tool in recognizing adnexal torsion with most common findings of tube thickening, ascites, and uterine deviation to the twisted side.13 MRI and ultrasound examination are especially helpful in the young or pregnant patients, because reliable information is provided without ionizing radiation.

In our case ultrasound was the only imaging modality used, as the patient’s pain was quite severe and warranted immediate surgical intervention. As the symptoms, signs and physical findings are associated with more than one condition such as ovarian torsion, acute appendicitis, ectopic pregnancy, acute salpingitis, tubo-ovarian abscess, ruptured ovarian cyst, degenerated leiomyoma, urolithiasis, intestinal obstruction or perforation,3 the main diagnosis is often established atlaparoscopy or laparotomy. Surgical management, whatever the cause determined, is always needed.

Laparoscopy is currently the most specific diagnostic tool for evaluating torsion and treating this condition. Early surgical intervention is recommended for pregnant women presenting with an acute abdomen irrespective of their gestation. Premature labour is far more likely, and the risk of maternal morbidity and mortality higher, if infection of the abdominal cavity is allowed to occur.14 A torted adnexal mass undergoing necrosis has potential to cause serious infection similar to that of a perforated appendicitis.14 Therefore in pregnant women the risk of complications associated with an acute abdomen outweighs the risks associated with abdominal surgery. Additionally, early intervention can sometimes salvage torted tissue by detorsion if it is performed in time.15

In this case, laparotomy was performed given the enlarged uterine size and the experience of the operating team which appears essential in the decision making. Despite these considerations, we believe that laparoscopy represents a valid treatment option until 32–34weeks of gestation.4 The salpingectomy was ideal for the gangrenous fallopian tube as a result of torsion.16

Our patient underwent a laparotomic salpingectomy because of the gangrenous fallopian tube. The post-operative period was uneventful and the patient successfully completes her pregnancy with no further complications.

Isolated fallopian tube torsion occurring in pregnancy is an uncommon event. This condition should be considered in the differential diagnosis of acute pelvic pain with cystic adnexal mass associated with a normal ipsilateral ovary. Imaging techniques may be suggestive but not conclusive. The laparoscopy is the gold standard for its definitive diagnosis and can also be used simultaneously to manage the disorder. Laparotomy should be relaxed in the third trimester of pregnancy. A timely diagnosis is important to prevent adverse sequelae and preserve fertility.

None.

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

©2017 Ouassour, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.