Journal of

eISSN: 2373-4426

Research Article Volume 10 Issue 1

1Department of Nursing, Arbaminch University, Ethiopia

2School of Nursing, Hawassa University, Ethiopia

Correspondence: Tomas Yeheyis, Department of Nursing, College of Medicine and Health Science, Hawassa University, Ethiopia, Tel +251975708574

Received: July 31, 2019 | Published: January 3, 2020

Citation: Mustefa A, Abera A, Aseffa A, et al. Prevalence of neonatal sepsis and associated factors amongst neonates admitted in arbaminch general hospital, arbaminch, southern Ethiopia, 2019. J Pediatr Neonatal Care. 2020;10(1):1-7. DOI: 10.15406/jpnc.2020.10.00404

Background: There are an estimated 2.9 million deaths worldwide from sepsis every year (44% of them in children under 5 years of age) and one quarter of these are due to neonatal sepsis. According to global burden of neonatal sepsis about 6.9 million neonates were diagnosed with possible serious bacterial infection needing treatment from these 2.9 million cases of neonates needing treatment occur in sub-Saharan Africa.

Method: An institution based cross sectional study with retrospective document review was conducted among neonates admitted to neonatal intensive care unit from December 2017 to December 2018 in arbaminch general hospital. Sample size was calculated by using single population proportion sample formula with a final sample size of 351. Data were collected a checklist. Using SPSS version 21 Binary and multiple logistic regressions have been used to observe the association between independent variables and dependent variable.

Result: The magnitude of neonatal sepsis was 78.3%. APGAR<6,PROM> 18 hours and duration of labour>12 hours were positively associated with neonatal sepsis where as gestational age > 37 weeks and birth weight >2500 grams were protective factors as evidenced by statistical result of 2.33(0.205-0.33), 1.32(0.71-0.84), 1.20(0.70-0.95), 0.85(0.34-0.815) and 0.12(0.04-030) respectively.

Conclusion and recommendation: The finding of this study shows that neonatal sepsis accounts the highest proportion cases amongst neonates admitted in the hospital. Gestational age, birth weight, APGAR score, PROM and duration of labour were found to be determinants of neonatal sepsis. Therefore, service utilization of mothers, early detection of risky situations and appropriate practice of newborn care can halt the problem.

Keywords: neonatal sepsis, neonates, neonatal intensive care unit

AMU, arba minch university; ANC, antenatal care; CS, caesarean section; DM, diabetic mellitus; EDHS, ethiopian demographic health survey; ELBW, extremely low birth weight; EONS, early onset of neonatal sepsis; GA, gestational age; GTP, growth and transformation plan; HIV, human immune virus; HSDTP, health sectors development transportation plan ; HTN, hypertension; LBW, low birth weight; LONS, late onset of neonatal sepsis; MAS, meconium aspiration syndrome; MDG, millennium development goal; MSAF, meconium stained amniotic fluid; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit; NMR, neonatal mortality rate; PROM, premature rapture of membrane; RH, reproductive health; SVD, spontaneous vaginal delivery; UTI, urinary tract infection; VLBW, very low birth weight; WHO, world health organization

Neonatal sepsis defined mostly as an infection occurring within the first 28days of life and it is characterized by signs of infection or presence of a microbe in the blood stream. The estimated global burden for neonatal sepsis was 2,202 per 100,000 live births; Neonatal sepsis contributes substantially to neonatal morbidity and mortality.

Generally speaking the epidemiology of sepsis is better known in adults than in children, yet neonatal and child mortality due to sepsis is a major problem. There are an estimated 2.9 million deaths worldwide from sepsis every year (44% of them in children under 5years of age) and one quarter of these are due to neonatal sepsis. The main pathogens of neonatal sepsis are gram-negative bacteria (Klebsiella, Enterobacter, Acinetobacter) and gram-positive bacteria (Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus [MRSA]).1–5 In neonatal intensive care units in LMICs a higher frequency of gram-negative bacteria is found, though in paediatric intensive care units the proportions of gram-negatives and gram-positives are similar and is an ongoing major global public health challenge.6,7

Regarding the current united nation estimate, the neonatal death in Ethiopia is reduced by 48% from the 1990 estimate to 28 per 1000 live births in 2013 and, the reduction rate of under-five mortality rate was about 67 % by the same year.8 The 2016 EDHS reported that neonatal mortality rate is 29/1000 live birth. Which has a reduction from the 2005 EDHS report of 39/1000 live births and 2011 EDHS report of 37/1000 live birth and by comparison The reduction from 2000 EDHS is estimated to be 41%.9

Preterm birth, asphyxia, tetanus and sepsis are reported to be the major causes of neonatal mortality in Ethiopia. Many women do not generally seek formal health care during pregnancy, child birth and puerperal. Less than third of women receive antenatal care and 90% are assisted by unskilled attendants: TBAs (26%) relatives (58%) or alone (6%).Almost no one (3.5%) receives postnatal care.10–23 In addition limited care for new born in health facilities and inadequate new born seeking practice contribute a lot to these problems.4,6,20

The first 28 days of life are times of opportunity and risk to a future life. Good nourishment and health will serve as a spring to healthy child hood where as illness will bring risks not only to this period but also to future child and adult hood. This issue will be under a shadow when it comes to developing countries. Care for the neonate have been given little attention in maternal and child health programs for many decades but now the world has turned face to neonates. Various efforts have been made by Ethiopian government as well supporting nongovernmental and international organizations to reduce neonatal mortality in the country. In addition some studies in Gondar, Mekele, tikur anbsa, Bahir dar, shashemene and debrezeit have been conducted focusing on neonatal mortality and sepsis. Results of this studies shows that neonatal sepsis still takes the first rank in admitting neonates to the neonatal intensive care units across different regions of the country. So it is important to do repeated additional researches regarding this topic and possibly synthesizing a meta analysis which in turn will help in identifying determinants of the condition.

Therefore this study was conducted deep in the southern part of the country, Arbaminch, to find the current prevalence of neonatal sepsis among neonates admitted in the hospital in the past one year and to determine the determinants of the problem. The study will give a picture from south Ethiopia and will create opportunity for stake holder to reduce it based on factors identified.

Study setting, design and period

Institutional based cross-sectional study was conducted in arbaminch town from February 1to 15, 2019. Arbaminch town is the administrative sit of Gamo zone located at 505km in south of Addis Ababa the capital city of Ethiopia and 275 km south west of Hawassa the capital city of south nations nationality people of regional with a population of 74,879. Arbaminch general hospital provides for inpatient and outpatient service for 200,747 people. 495 neonates were admitted and has been given care in the neonatal intensive care Unit during the study period.

Sample size determination and sampling technique

Sample size was determined using single population proportion formula by considering P-value of 33.8% from previous research in wolita zone, Ethiopia [29] 95%Confidence interval (CI), and 5% margin of error. Sample size was calculated as follows

Where

n= required sample size

Z= the standard normal deviation at 95% confidence interval; =1.96

P= proportion of neonatal sepsis among neonates admitted in NICU with prevalence of 33.8

d= margin of error that can be tolerated, 5% (0.05)

1-p = proportion of population that do not possess the character of interest.

Therefore,

By considering non response rate 5%, our total sample size was 399 neonates.

Total number of our study population was less than 10,000 mean that a total number of neonates admitted to this two hospital within one year was 626, so correction formula was used, that the final sample size was 244 neonates.

To select samples the total number of neonates who has been admitted in the NICU during the study period has been taken from the registration book in the unit. After that the charts has been reviewed for the presence of a complete data within them which gives us 480 charts with a complete data. Charts’ matching the number of the sample size required has been then selected by computer generated random sampling method. In this study neonatal sepsis is asserted when a medical diagnosis of the neonate has been stated as neonatal sepsis in his/her medical record chart by the physician who has examined the infant at that time.

Data collection tool and technique

The data was collected using record review check list adapted by reviewing relevant literature, the appropriate to address the study objectives. The check list contains questions and statements in four parts assessing: Socio-demographic characteristics; maternal obstetrics history, maternal medical condition and part which assesses neonate’s general birth and health related conditions. This involves going through Log book records of neonates in the study period and then medical files were traced using the patient card numbers on the log book registry. If there was incomplete maternal information on the neonatal card, the maternal card was traced by using neonatal card number. Two diploma nurses have been recruited as data collectors and were supervised by two Bsc nurses.

Data analysis

The collected data were cleaned, coded and entered into Epi info version 7 statistical software package. The statistical analysis was done using SPSS version.21 Frequency distribution for selected variables was performed. The statistical significance and strength of the association between independent variables and an outcome variable was measured by Bivarate logistic regression model. A variable P value less than 0.25 was transferred to multivariable logistic regression model to adjust confounders’ effects and a p value less than 0.05 was considered as significantly associated in this model. Finally, the results of the study were presented using tables, figures and texts based on the data obtained.

Data quality control

Before the data collection, Intensive training for data collectors was given for two days. Continues supervision of data collection process was carried out to assure the quality of data. Finally, the collected data was carefully checked on daily basis for completeness, outlier and missing value as well as consistencies. Moreover, the collected data were coded, cleaned and explored before analysis.

Ethical Consideration

Ethical clearance was sought from Arbaminch University, college of medicine and health science ethical review board. After explaining about the purpose and the possible benefit of the study, permission to gather data was obtained from the medical director of the hospital and head of the neonatal intensive care unit. The respondent’s privacy and confidentiality of the data were assured throughout the study.

Socio demographic characteristics

351 chart of neonates have been reviewed in this study, among this 208 (59.3%) were male and 143 (40.5%) were female, 292(83.2%) were age less than or equal to 7 days and 59(16.8%) were age greater than 7 days. Majority 274(78.1%) of mothers and care givers of neonates were in the age group between 21 and 35. From all mothers and care givers 204(58.1%) came from urban and 147(41.9%) were from rural (Table 1).

Variable |

Frequency (%) |

Percent (%) |

Age of mother |

|

|

<20 |

27 |

7.7 |

Residence |

||

Urban |

204 |

58.1 |

Age of neonate |

|

|

</=7 day |

295 |

84 |

sex of neonate |

||

Male |

208 |

59.3 |

Female |

143 |

40.5 |

Table 1 Socio demographic profiles of study participants in Arba Minch general hospital, 2018

Maternal and neonatal health related characteristics

Among the total 351 neonates recruited to the study only 6(1.7%) of the mothers of neonates had Urinary Tract Infection on admission of the neonate. From all the mothers of neonates in the study mother who had history of Meconium Stained Amniotic Fluid during delivery were 29(8.26%). Concerning duration of labour majority 227(64.7%) had a labour lasting less than 12 hours and the rest 124(35.3%) had a labour taking greater than or equal to 12 hours. 206(58.69) of the neonates in this study had normal birth weight and 145 (41.31%) had low birth weight. 104(29.62%) have had low APGAR score<6 and 247(70.38%) had an APGAR>7. From the total participants in the study 210 (59.83%) and 141(40.17%) were term and pre term babies respectively (Table 2).

Variable |

Frequency(n) |

EONS |

LONS |

History of UTI(STI) |

6 |

5 |

1 |

Antenatal care history |

351 |

217 |

58 |

History of foul smelling liquor |

1 |

1 |

0 |

History of choroamenionitis |

|

2 |

0 |

History of MAS |

25 |

22 |

3 |

Gestational age<37 weeks |

141 210 |

82 135 |

7 51 |

Time of rupture of membrane<18 hour >/=18hour |

237 114 |

140 77 |

45 13 |

Duration of labour<12 hour >/=12hour |

224 124 |

143 84 |

40 18 |

Sex |

209 |

132 |

27 |

Birth weight <2500gm |

145 |

81 |

6 |

APGAR score </=6 score |

132 219 |

96 121 |

8 50 |

Gestational Age </=36week |

141 |

82 |

7 |

Type of neonatal sepsis EONS LONS |

217 58 |

|

Table 2 Maternal and neonatal health related characteristics of study participants in arbaminch general hospital, 2018

Prevalence of neonatal sepsis

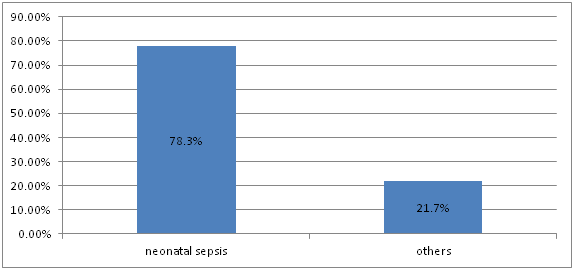

Among 351 neonates who were admitted in NICU of Arbaminch general hospital 275(78.3%) had neonatal sepsis and the rest 76(21.7%) have been admitted for other diseases. From those 275 neonates who have been admitted for neonatal sepsis 217(78.9%) were admitted for Early Onset Neonatal Sepsis and 58(21.1%) for Late Onset Neonatal Sepsis (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Prevalence of neonatal sepsis among neonates admitted in arbaminch general hospital from December 2017 to December 2018.

Factors associated with neonatal sepsis

Bivarate and multivariate logistic regression analysis had been done to identify pridictors of neonatal sepsis. In bivariate analyses, neonatal sepsis was significantly associated with female sex, birth weight, gestational age, meconium stained amniotic fluid, APGAR score, duration of labour and PROM. After adjusting for confounders with multivariable logistic regression model birth weight, gestational age, APGAR score, duration of labour and PROM were significantly associated with neonatal sepsis. Based on the finding in this study neonates born at a gestational age>37 wks had 15% reduction in the risk of developing neonatal sepsis compared to babies born preterm. (AOR (95%CI=0.85(0.34-0.815) Neonates born from mothers who had a labour with a PROM>18 hrs were 1.32 times more likely to develop neonatal sepsis compared to those neonates whose mothers had a labour with a PROM<18 hrs. (AOR (95%CI=1.32(0.71-0.84)). Likewise neonates born from mothers who give birth by a labour lasting>12 hours were 1.2 times more likely to develop neonatal sepsis compared to neonates born from mothers who give birth by a labour lasting <12 hours. (AOR (95%CI=1.20(0.70-0.95)). Regarding birth weight neonates who had a birth weight >2500gms had 88% reduction in the risk of developing neonatal sepsis compared to neonates who had a birth weight<2500grams. (AOR(95%CI=0.12(0.04-030)). On the contrary neonates who had an APGAR score<6 were 2.3 times more likely to develop neonatal sepsis compared to neonates who had an APGAR score>7. (AOR(95%CI=2.33(0.205-0.33)) (Table 3).24–45

Variable |

Sepsis |

COR 95%CI |

AOR95%CI |

|

|

No |

Yes |

||

Gestational age |

52(68.4)

|

89(32.4) |

1 |

0.85(0.34-0.815)** |

Birth weight |

58(76.3 |

87(31.6) |

1 |

0.12(0.04-030)** |

PROM |

52(68.4) |

185(67.3) |

1 |

2.33(0.205-0.33) |

APGAR </=6score |

28(36.8) |

104(37.8) |

3.71(0.57-1.62) |

2.33(1.25-4.33)** |

Sex |

49(64.5) |

160(58.2) |

4.25(0.45-1.29) |

0.79(0.46-1.35) |

MSAF |

5(17.2) |

24(82.8) |

3.43(0.50-3.68) |

1.36(0.49-3.80) |

Duration of labour |

29(23.4) |

95(76.60) |

3.28(0.69-1.97) |

1.20(0.70-0.95)** |

Table 3 Determinants of neonatal sepsis among neonates admitted in arbaminch general hospital, 2018

As to the first objective of the study the prevalence of neonatal sepsis is 78.3%. The magnitude of neonatal sepsis found in this study is congruent with the studies conducted in Shashamene, Nigeria and Debrezeit.34,43,46 But the result in this study is higher than the studies in Gondar, and Egypt.28,37 This deference could be due to the socio-demographic differences in the study areas and differences in the way neonatal sepsis has been asserted because some of the studies have used confirmatory blood culture to assert neonatal sepsis to the study which is difficult to apply in this study area due to unavailability of the facility. In this study, there were different factors that determine neonates’ chance of developing neonatal sepsis.47,48 In this regard neonatal sepsis was significantly lower among neonates born at term compared to those neonates who were born pre term. This finding is similar with the studies conducted in Mexico, Tanzania, Tikur Anbsa, Gondar.13,28,37,49 This might be because pre term babies are underdeveloped, having a compromised immune system and poor breast suckling which predisposes them poor nourishment and body defense.

In this study PROM>18 was positively associated with neonatal sepsis. Which is similar with Mekele, Mexico and Nigeria.13,43,45 Likewise neonates born from mothers who give birth by a labour lasting>12 hours were more likely to develop neonatal sepsis compared to neonates born from mothers who give birth by a labour lasting <12 hours. Which is a factor not identified in a previous studies. This can be explained by the fact that in mothers with a labour prolonging longer than 18 hours after rupture of membrane increases neonates chance of suffering from infection from the genital tract. In addition a prolonged labour will predispose the new born to suffocation and aspiration of amniotic as well other fluids in the way; which intern increases the risk for neonatal sepsis. This study found out those neonates who had a birth weight >2500gms had significant reduction in the risk of developing neonatal sepsis compared to neonates who are low birth weight. This result is similar to the findings in studies done in Mexico, Tanzania, Gondar and tikur anbesa.13,28,37,49 This might be because neonates who are low birth weight have reduced subcutaneous fat, increased risk of hypothermia due to high body surface area to weight ratio, and poorly developed immune system related to low birth weight.

On the contrary an APGAR score<6 have been positively associated with neonatal sepsis compared to an APGAR score>7. It is congruent with the finding from studies conducted in Gondar and Mekele.37,45 This can be explained by the theory that a neonate who had a compromised APGAR score might have been exposed to infection causing microbes at birth or might have a decreased respiratory other body function at birth which pose a risk to infection later in life compared to those neonates functioning well at birth.

The finding of this study shows that neonatal sepsis accounts the highest proportion cases amongst neonates admitted in the hospital. This problem was determined by Gestational age>37, Birth weight>2500gms, PROM>18,APGAR<6 and Labour lasting more than 12 hours. Well tailored identification of risks during labour, triaging those labours and managing the labour to decrease labour du ration as well Prolonged rapture of membrane can decrease the risk of neonatal sepsis. In addition early detection and prevention of infection should be strictly applied to pre term, low birth weight and poor APGAR scoring babies.

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available with some restrictions for ethical reasons from the corresponding and Co- authors.

AM, AA, AA and TA conceived and designed the study and analyzed the data. TY prepared the manuscript. ND and TY assisted with the design conception and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors have read and approved this manuscript.

The authors are grateful for the data collectors and study participants.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

There is no source of funding for this research. All costs were covered by researchers.

©2020 Mustefa, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.