Journal of

eISSN: 2373-4426

Research Article Volume 12 Issue 2

1Assistant Professor, Department of Paediatric Haematology and Oncology, National Institute of Cancer Research and Hospital, Bangladesh

2Associate Professor, Department Radiology, Gleneagles Hospital Hong Kong, Bangladesh

Correspondence: Ashis Kumar Ghosh, Assistant Professor, Department of Paediatric Haematology and Oncology, National Institute of Cancer Research and Hospital, Bangladesh

Received: December 24, 2021 | Published: March 11, 2022

Citation: Ghosh AK, Al-Amin ANM, Fan H. Pediatric primary mediastinal lymphoma – a descriptive study of a single cancer center of Bangladesh. J Pediatr Neonatal Care. 2022;12(2):50-56. DOI: 10.15406/jpnc.2022.12.00454

Lymphomas involving the mediastinum occur in a wide age range and represent heterogeneous histological subtypes with various clinical symptoms and complex radiological findings. However, this cross sectional study that describes the clinical, pathological and radiological features of Bangladeshi pediatric patients aged less than 18 years. The study conducted in National Institute of Cancer Research and Hospital with 71 primary pediatric mediastinal masses, diagnosed between 2014 and 2018 and evaluated at enrollment or admission in the department of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology (PHO). The presence of extra thoracic lymph node involvement was excluded from the study. All patients were underwent computerized tomography (CT) or ultra sound (USG) guided needle biopsy. Only diagnosed cases of lymphoma (N-38) with mediastinal mass on chest radiography or CT scan were taken for analysis.

Mediastinal lymphoma was 38 in number which, 16.30% of total (N-233) pediatric lymphoma of PHO. The median age of the patients was 11.43 years with mostly (68.42%) in 10-17 years age group. Males and females were equal in number. Common symptoms of the patients were fever, cough, dyspnea, chest pain. Most common side involved by tumors were anterior mediastinum 68.42% (N-26) followed by middle mediastinum 50% (N-19), Posterior mediastinum 10.53% (N-4) and superior mediastinum 7.9% (N-3). More than one mediastinal anatomical side involvement was in 34.21% (N-13) cases. Tissue biopsy revealed non Hodgkin Lymphoma were 86.84% (N-33), Hodgkin Diseases 10.53% (N-4) and T-lymphoblastic lymphoma (LBL) 2.63% (N-1). All tumors were malignant with 73.68% metastasis.

Pediatric mediastinal mass is a troublesome condition for doctors during emergency management at presentation, for interventional radiologists during tissue biopsy, pathologists during histopathological examination and oncologists during treatment planning. A few publications narrated the pediatric mediastinal oncological conditions but in Bangladesh no such study has conducted before addressing the pediatric mediastinal lymphoma. So we conducted this study to show the importance of development of infrastructure to manage these type of tumors successfully.

Keywords: Mediastinal, tumors, childhood

Primary mediastinal lymphoma is the lymphoma involving thymus, mediastinal lymph nodes, and mediastinal organs like heart, lung, pleura, and pericardium without any evidence of involvement of distant organs at the time of presentation.1 But for all practical purposes, primary mediastinal lymphoma refers to the lymphoma arising from the central lymphoid organ, thymus.2 So it is also sometimes called primary thymic mediastinal lymphoma. Tumors arising from the mediastinum are rare in children or adolescents and most such tumors are malignant in nature.2 Mediastinal lymphoma may be primary or secondary and are usually involved secondarily as a part of the systemic disease.3 Lymphoma comprises about 12% of all the mediastinal tumors in adults,4 however it constitutes 50% of the pediatric mediastinal mass.5

Hodgkin lymphoma( HL) is more common in adolescents, while Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) occurs more frequently in childhood6,7 and HL has been reported 33% to 56% of pediatric mediastinal lymphomas8,9 but Tansel et al. reported an adult mediastinal lymphoma like prevalence of Hodgkin’s lymphoma (60%, N-6/10) and Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (40%, N-4/10) among the pediatric population.10 Lymphomas of the mediastinum can originate either from the thymus or the lymph nodes. Thymic lymphomas show unique pathologic characteristics distinct from common nodal lymphomas.11 Two primary representative T- and B-cell lymphomas arise in the thymus: precursor T-lymphoblastic lymphoma/leukemia (T-LBL) and primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma (PMLBCL). T-LBL can be relatively easily excluded because of its uniform histologic features and by confirmation of the pathognomonic marker TdT by immunohistochemistry (IHC). On the contrary, the differential diagnosis of B-cell lymphomas is much more complicated.12 Lymphoblastic lymphoma (LBL) are a group of mediastinal lymphoma which are aggressive neoplasms of the precursor immature cells of lymphoid lineage either committed to the T- or B-lineage. LBL is the second most common subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma in children.13 Of note, only approximately 10% of LBL express B-cell markers in contrast to approximately 85% of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).14 The distinction between leukemia and lymphoma is arbitrary and based on the extent of involvement of bone marrow (BM). It is usual to diagnose patients with ≥ 25% lymphoblasts in BM as having ALL, whereas patients with extra-medullary disease and less than 25% blasts in BM are diagnosed as LBL.15,16

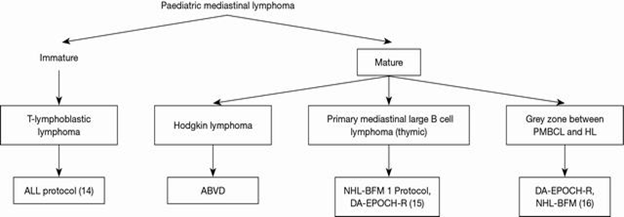

Pediatric mediastinal lymphoma is a bit different than adult mediastinal lymphoma. Among the pediatric mediastinal lymphomas, primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma (PMLBCL) and classic Hodgkin lymphoma (CHL) represent two major types of mature B-cell lymphomas of the mediastinum,17 although other types of B-cell lymphomas such as marginal zone lymphoma do occur at a low incidence.12 Other types of aggressive and indolent non-HLs (NHLs) can occur in mediastinal lymph nodes and mediastinal organs (heart, lung, pleura, and pericardium) in adults; however, they are extremely rare in pediatric age group.2 Mediastinal lymphomas can be broadly divided based upon the cell of origin into the immature (blastic) type and mature (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Common pediatric mediastinal lymphoma and Treatment protocols.18-20 PMBCL, primary mediastinal large B cell lymphoma; HL, Hodgkin lymphoma; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

Mediastinal masses have always been a diagnostic as well as therapeutic dilemma for medical professionals. More over interpretation of mediastinal biopsy is often challenging even for experienced pathologists especially when a hematolymphoid neoplasm is suspected.17 Most of the studies publish in literatures reflecting adult mediastinal lymphoma. But we know that the clinical profile, diagnostic challenges and types of mediastinal lymphoma in children is different as compared to adults. For example, distinguishing Hodgkin lymphoma from PMBCL can be challenging. Both diseases can affect younger adults and both entities can be similar histologically. Flow cytometry studies can be helpful, as many patients with classic Hodgkin lymphoma have neoplastic cells that express CD15 and CD30, while they lack expression of B-cell markers but PMBCL patients express B-cell markers and have weak CD30 expression.21

To the best of our knowledge, there have been no prior studies in Bangladesh involving the pediatric populations focusing on the epidemiology, diagnostic challenges and disease pattern. Therefore, we conducted this study to identity the common mediastinal lymphomas, their mode of presentations, common complications, which will be helpful for understanding the burden of this cancer, their differential diagnosis and emergency management by clinicians.

We collected data for this cross-sectional study at the edge of enrollment or admission of patients in our department after taking written consent from participants or parents. Patients aged less than 18 years with pathologically proven mediastinal tumors of all types from January 2014 to December 2018 at Department of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology (PHO) of National Institute of Cancer research and Hospital (NICRH) were included in this study but only lymphoma cases were taken for analysis.

Data such as patient’s sex, age of disease onset, initial clinical symptoms, diagnostic procedure and complication at presentation such as airway obstruction, pleural effusion, pericardial effusion, superior vena cava (SVC) syndrome were collected. As a part of the workup, ultrasonography and CT scan of the mediastinum were helpful in identifying the location, size and subsequent core biopsy or open biopsy if needed were performed. Diagnosis was confirmed by histology, immunohistochemistry, immunophenotyping (flow cytometry) and bone marrow examination.

Statistical analysis was done by PSPP software.

Inclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria

There were 71 cases having abnormal mediastinal masses detected on initial diagnostic workup on the chest radiology. Among them hematological malignancy were 38 case and non- hematological were 33 cases (Figure 2). Total pediatric tumors during the 5 years (2014-2018) were 2242. Total hematological tumors were 18.91 % (N-424) of total pediatric tumors. During the 5 years total lymphoma (HL &NHL) at PHO were 233, which were 54.95% of total pediatric hematological tumor and mediastinal lymphoma were 38 in number which were 16.30% of total lymphoma.

Table 1 depicted the median age of onset was 11.43 years (age range: 2.5–16 years). Males and females are equally (Male/Female-19/19). Common age group was 10-17 years (68.42%) followed by 5-10 years (23.68%) and 0-4 years (7. 90%). Most of the patients came from Dhaka and Mymenshing division (N-8, 21.05%), least number of child came from Sylhet division (N-1, 2.63%). Almost all patients were poor (N-30, 78.95%), rest were in middle income group (N-8, 21.05%). Maximum patients were village dwellers (N-34, 89.47%), others from town (N-4, 10.53%). Diagnostic delay that means from start of symptoms to final diagnosis or start of treatment was 2.92 months (Range- 6 to 144 months).

Sl.no |

|

Frequency |

% |

1. |

Age |

11.43 years |

7.90 |

2. |

Gender |

Male -19 |

50 |

3. |

Division |

Dhaka - 8 |

21.05 |

4. |

Village dweller Town dweller |

Village 34 |

89.47 |

5. |

Socio economical Condition |

Poor 30 |

78.95 |

6. |

Family History of Cancer |

Present 1 |

2.63 |

7. |

Diagnostic delay |

Mean 2.92 |

|

Table 1 Baseline clinical characteristics of Mediastinal Lymphoma

Clinical presentations of children with mediastinal lymphoma have been demonstrated in Table 2. The most common presentation of our study were symptoms like fever and cough both were 81.58%, respiratory distress (76.32%), chest pain (50 %) and chest deformity (36.84 %). Less common findings were Limb weakness, features of hypothyroidism, lung collapse. hemoptysis, B-Symptoms, superior vena cava syndrome (SVCs).

Sl.no |

Signs and Syndromes |

Frequency |

% |

1. |

Fever |

31 |

81.58 |

2. |

Cough |

31 |

81.58 |

3. |

Respiratory distress |

29 |

76.32 |

4. |

Chest Pain |

19 |

50 |

5. |

Chest deformity |

14 |

36.84 |

6. |

Upper limb weakness |

3 |

7.89 |

7. |

Hypothyroid features, Lung collapse |

2 |

5.26 |

8. |

Hemoptysis, B-Symptoms, SVCs |

1 |

2.63 |

Table 2 Clinical features of mediastinal lymphoma

For diagnosis of mediastinal mass standard chest radiograph (100%), Chest ultrasound (2.63%) and Computed tomography (92.11%) were used (Table 3). Tumor tissue was collected by ultrasound-guided biopsy in 28.95 % (N-11) and CT guided biopsy in 71.05% (N-27) of cases. Immunophenotype needed in 7 cases (18.42%) and bone marrow study reports were available in 78.95% (N-30) cases.

Sl.no |

Investigations/Procedure |

Frequency |

% |

1. |

CXR |

38 |

100 |

2. |

Tissue Biopsy Collection- |

11 |

28.95 |

3. |

Immunophenotype done |

7 |

18.42 |

Table 3 Procedures for diagnosis of mediastinal lymphoma

The individual tumor occupied the mediastinal anatomical area was shown in Table 4. Summarizing the table, anterior mediastinal involved in 26 cases (68.42%), followed by middle mediastinal 19 (50%), posterior mediastinal 4(10.53%) and superior mediastinal 3(7.9%). Among them 34.21% (N-13) patients involved more than one side. Most common effusion were in pleural cavity 60.5% (N-23) followed by pericardial effusion 10.5 % (N-4).

Sl. no |

Location, diagnosis & complications |

Frequency |

% |

1. |

Tumor location |

16 |

42.11 |

2. |

Effusion |

4 (1:2:1) |

10.53(2.63: 5.26: 2.63) |

3. |

Pneumothorax |

1 |

2.63 |

4. |

Diagnosis |

33 |

86.84 |

5. |

Benign |

0 |

0 |

6. |

Metastasis (NHL:HL:ALL) |

28 (24:3:1) |

73.68(63.15:7.90:2.63) |

7. |

Metastatic sides |

23 |

60.53 |

Table 4 Location, diagnosis and complications of mediastinal lymphoma

Final diagnosis was made by tissue biopsy, Flow cytometry and immunohistochemistry where needed. Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma were 86.84% (N-33), Hodgkin lymphoma 10.53% (N-4) and T-lymphoblastic lymphoma (LBL) 2.63% (N-1). All tumors were malignant with 73.68% metastasis, where in Pleura 60.53% (N-23), Pericardium10.53 %( N-4), Lung 5.26% (N-2) and Rib 2.63% (N-1)

Lymphomas represent 13% of all pediatric cancers and most commonly occur in the prevascular mediastinum.6,7 but in our study Lymphomas represent 10.39% (233/2242) of all pediatric cancers. This data is nearer to previous study. In our finding mediastinal lymphoma was 53.52% (N-38) of total mediastinal tumors (N-71). But in a Japanese study, lymphomas comprise about 12% of all the mediastinal tumors.4 Few studies show lymphomas forming a huge burden (50%) of the pediatric mediastinal masses.5 Our study correlate with second one. In the present study mediastinal lymphoma were 38 in number which, 16.30% of total lymphoma (N-233) of our department. But Duwe BV et al revealed 10% of lymphomas which involve the mediastinum are primary.22 Our incidence is higher than the report of Duwe et al. In present study median age of onset was 11.43 years (age range: 2.5–16 years). Males and females were equally in number i.e. M:F=1:1. In a study by Temes et al found 59% were male (13/22) and 41% were female (9/22) with median age was 11 years.23 Our observation is nearer to these findings. An American study showed that common age of childhood lymphoma was 10-20 years.24 In our finding the common age group of mediatinal lymphoma was 10-17 years (68.42%).

Most of the patients came from Dhaka and Mymenshing division (both were N-8, 21.05%), least number of child came from sylhet division (N-1, 2.63%). Most possible cause of this disparity of patient’s number was distance of patient’s house from our center. Maximum patients were economically poor (N-30, 78.95%) and village dweller (N-34, 89.47%). In a previous study of our Institute by Jabeen S et al.25 reported that the most of the children with cancer came from the rural areas (67%) compared to 33% from urban areas. Early diagnosis remains a key factor and a fundamental goal in pediatric oncology and delayed diagnosis may also be associated with huge economic cost.26 We defined “Diagnostic delay” that means from start of symptoms to final diagnosis or start of treatment. In our study diagnostic delay was 2.92 months (Range- 6 to 144 months). A study from Nigeria by Chukwu et al. median total lag time to diagnosis of cancer in a study was 15.8 weeks.27 But in the developed nation like Singapore diagnostic median total delay was 5.3 weeks (range 0.1–283.1 weeks).28 Diagnostic delay depend on parent’s understanding about the diseases, parents economical condition, type of cancer, health delivery system.

The clinical and radiological presentations of lymphomas involving the mediastinum are complex and nonspecific.22,29 The most common presentation of our study were symptoms like fever and cough both were 81.58%, dyspnea 76.32% and chest pain 50 %. Chen L et al.30 of china, estimated cough in 67.7%, chest pain 22.6% fever 32% and dyspnea 38.7%. But in a child hospital of Taiwan the symptoms like fever was 31.5%, cough 57.9%, dyspnia 68.4% and chest pain was 26.3%.31

Thoracic lymphoma may present as deformity of chest wall due to large tumor mass or lymph node enlargement. In our finding chest wall deformity was 36.84 % but in France it was only 2%.32 Others less common findings of our study were limb weakness, features of hypothyroidism, lung collapse, hemoptysis, B-Symptoms, superior vena cava syndrome (SVCs).

For diagnosis of mediastinal lymphoma, all the patents initially assessed by Chest X-ray, one patient done Ultra sonogram and 92.11% (N-35) patients were evaluated by CT scan. CT guided fine-needle biopsy were used in 71.05% (N-27) patients by an interventional radiologist to obtain tumor tissue, rest of the patients (28.95%, N-11) underwent ultrasound guided Needle biopsy. In this study bone marrow examination were done in 78.95% (N-30) cases and immunophenotype in 18.42% (N-7) tissue to confirm this diagnosis. Ultrasound-guided biopsy is a useful technique for anterior mediastinal lesions with a good diagnostic yield and minimal complications. As most of the mass of our patients were in anterior mediastinal, so radiologists used less expensive USG guided needle biopsy in 28.95% cases.

Immunohistochemistry is more important in mediastinal lymphoma. In histopathology examination of tissue, primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma (PMBL) shares a number of features with classical hodgkin lymphoma (CHL), particularly the nodular sclerosis type.33. So the diagnosis of mediastinal lymphoma involves a multimodal approach and includes a meticulous histological examination followed by IHC evaluation. Rare cases may require even cytogenetic and molecular diagnosis.34 Due to financial constraint of our patients we have to do poor number (N-7) of Immunophenotype of our samples.

In the present study anterior mediastinal involved in 26 patients (68.42%), followed by middle mediastinal 19(50%), Posterior mediastinal 4(10.53%) and superior mediastinal 3(7.9%). Regarding pediatric mediastinal lymphoma Gun F et al reported that anterior mediastinal involved in 77.27 % (N-17) followed by middle mediastinal 22.73% (N-5) cases.35 A large mediastinal lesion may appear to involve multiple compartments or extend from one compartment to another.36 In our study lymphoma of 13 children (34.21%) involved more than one compartments.

In our study non Hodgkin Lymphoma were 86.84% (N-33), Hodgkin lymphoma 10.53% (N-4) and T-lymphoblastic lymphoma (LBL) 2.63% (N-1). We know Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) is more common in adolescents, while non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) occurs more frequently in childhood.6 In a report from china by Chen et al showed childhod HL and NHL were 22.6% and 77.4% respectively.30 Our findings correlate the data of Chen et al but different types of observation made by Tansel et al.10 where HL was 60% and NHL was 40% in pediatric age group.

Complications of lymphomas involving the mediastinum commonly included pleural and pericardium effusion. Sometimes Pericardial effusion may be the presenting sign in NHL.37 In present study plural and pericardial effusion were 60.53% and 10.53% respectively. Mallick et al2 reported involvement of adjacent organs—lung and pleura and may present as a pleural and pericardial effusion, which in 30% of cases. Chen L et al.30 outlined pleural effusion in pediatric mediastinal lymphoma were 78.3%, pericardial effusion 47.7%. Our data regarding plural effusion is nearer to second study but incidence of pericardial effusion of Chen et al is much more than our finding. All the tumors were malignant in nature with 73.68 % (N-28) metastasis and maximum metastasis was due to NHL (63.15%, N-24) followed by HL (N-3, 15.7%) and LBL (N-1, 2.63%). Other less common sides of metastasis were Lung 5.26% (N-2) and Rib 2.63% (N-1). Some tumors did metastasis in more than one side.

One patient diagnosed as T-lymphoblastic lymphoma (LBL). Precursor T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma (LBL) and T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) are considered same disease with different clinical presentations. World health organization classification includes both T-LBL and acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) under a common umbrella, precursor T-ALL/LBL. Precursor T-cell LBL occurs most frequently in late childhood, adolescence or young adulthood, is considered a type of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and constitutes 2% of these tumors.38 Our patient revealed a normal hematological and bone marrow study but X-ray and CT scan chest showed almost complete opacification of the left lung with pleural effusion and shift of mediastinum. Bone marrow examination was normal. The histopathological findings were consistent with the diagnosis of malignant lymphoid neoplasm. On immunohistochemical analysis mediastinal tumor cells expressed the LCA, CD3, CD4, CD7, CD99, and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdΤ). Tumor cells were negative for CD20, CD79a, CD30, CD15, CD56. The Ki67 proliferative index was approximately 73%.

Greatest drawback of our study was the limited number of cases from a single hospital. Though the low incidence of mediastinal tumors in general populations, there were only 38 cases of mediastinal lymphoma. Diagnostic approach including extended panel of IHC, in-situ hybridization, flow cytometry and molecular profiling for all cases were not possible to use in this study. Pediatric mediastinal lymphomas presented distinctive histological subtypes, which is essential for proper diagnosis and management. So further studies are needed for more detailed understanding.

Pediatric mediastinal lymphomas constitute a significant proportion of pediatric mediastinal tumors. Clinically and radiologically the major mediastinal lymphomas are NHL in our study, followed by Hodgkin Lymphoma and leukemia (T-ALL) also. The clinical presentation ranges from a simple fever to severe life-threatening respiratory distress. In our study Lymphomas represent 10.39% of all pediatric cancers and mediastinal lymphoma was 53.52% of total mediastinal tumors. Among Lymphomas major tumors were Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma (86.84%) and the common age group of mediastinal lymphoma was 10-17 years. These findings will be helpful for diagnosis of mediastinal lymphoma in clinical practice in future.

The diagnosis of lymphoma can be difficult to make when a biopsy specimen is small. Mediastinal tissue collection and diagnosis was a great problem in our country even a decade ago. Till now tissue collection and diagnosis are not possible in all the pediatric oncology centers of Bangladesh. Due to limited availability of tissue (core needle biopsy), care of handling of tissue samples is required for optimal utilization.

To overcome the diagnostic difficulties of mediastinal lymphoma in future, we have to establish adequate sample collection centers with rich diagnostic tools like IHC, in-situ hybridization, flow cytometry and molecular profiling for all cases. We also need more technological development in the field of mediastinal Lymphoma management.

Authors report no conflicts of interest.

©2022 Ghosh, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.