Journal of

eISSN: 2373-4426

Review Article Volume 5 Issue 6

1Seaside Pediatrics, USA

2Department of nursing, Columbia University Medical Center, USA

Correspondence: Rita Marie John, Columbia University School of Nursing, Associate Professor of Nursing at CUMC, Director, Pediatric Primary Care Nurse Practitioner Program, USA

Received: November 09, 2015 | Published: November 23, 2016

Citation: Owen EK, John RM (2016) Overcoming Barriers to Treatment Adherence in Adolescents with Cystic Fibrosis: A Systematic Review. J Pediatr Neonatal Care 5(6): 00204. DOI: 10.15406/jpnc.2016.05.00204

Aims and objectives: To examine the recent literature on the barriers to adherence in adolescents with cystic fibrosis (CF) and to propose recommendations for providers to improve adherence and overcome these obstacles.

Background: Non-adherence in chronically ill adolescents has become a public health concern as it contributes to a significant increase in morbidity and mortality. CF is a progressive, genetic disease with a particularly complex and time-consuming treatment regimen. Adolescent patients with CF fail to achieve optimal adherence goals.

Design: Systematic review using the guidelines of the Cochrane Collaboration described in the 2009 PRISMA statement.

Methods: PubMed, Web of Science and Google Scholar were searched from 1/2009 to 10/2014. A systematic review of the literature was done to identify the primary barriers to treatment adherence in adolescents with CF.

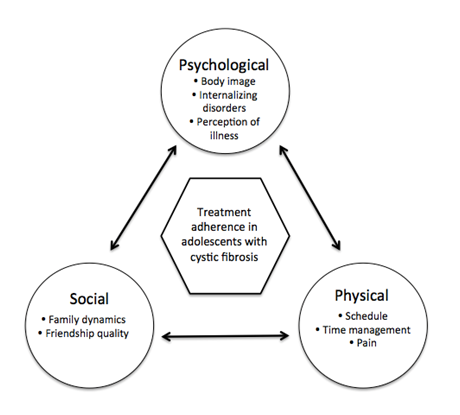

Results: Ten studies involving 512 participants with an average age range of 12.0 to 19.3 years across 4 countries were included. We classified the data into three main categories of barriers to adherence: psychological barriers (body image, internalizing disorders, perception of disease), physical barriers (schedule, time management, pain) and social barriers (family dynamics, friendship quality).

Conclusions: There are numerous potential obstacles to adherence for adolescents with CF. Whether the barriers are physical, psychological or social, the aim of the provider is to identify areas of strength and weakness in the treatment regimen, customize the interventions in the context of their lifestyle, and then set realistic goals for improvement.

Relevance to clinical practice: Screening adolescents with CF for potential psychological, physical or social obstacles to treatment compliance will allow the provider identify problematic areas and prioritize their clinic visits accordingly.

Keywords:adolescents, compliance, systematic review, chronic illness, genetics, therapeutic relationships, psychological, social coping, pediatrics

CF, cystic fibrosis; CFTR, CF trans-membrane conductance regulator; ECFS, European cystic fibrosis society’s; SAGE, sample size, age, gender, and ethnicity; MPR, medication possession ratio; MARS, medication adherence report scale; TARS, treatment adherence rating scale; TAQ-CF, treatment adherence questionnaire-cystic fibrosis; CCFMP, confidential cystic fibrosis management profile; DSM, diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders; MICS, mealtime interaction coding system

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a progressive genetic disease affecting multiple body systems. CF is a result of a mutation in the CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene. The progression of CF can be slowed through the patient’s commitment to rigorous, time-consuming daily treatments. The recommended therapies include inhaled antibiotics, inhaled mucolytics, chest physiotherapy, oral vitamins, and pancreatic enzyme supplementations.1 While there have been developments in gene modulating therapies to alter the underlying defect, the emphasis of management remains symptom control and the deceleration of irreversible injury. The primary goals of the CF treatment regimen include prevention of lung damage and pulmonary exacerbations; optimization of nutritional status; early identification and treatment of comorbidities; relief of pain and associated symptoms; and the improvement of quality of life.2 The substantial number of therapies and the associated intricacies challenge providers, patients, and their families to achieve optimal adherence goals.2 Non-adherence contributes to a significant increase in morbidity and mortality of individuals with CF and is a top priority for future CF research.3

Rationale

The number of people living with CF is increasing due to improvements in disease management.2 The median predicted survival age is 41.1 years old.4 Developmental changes, including a greater amount of time invested in peer relations, emerging responsibilities, heightened body image, and changing family dynamics affect the adolescent’s commitment to treatment. More independence allows for more time spent away from caregivers and a shift in responsibility to the adolescent.5 Social isolation due to infection control guidelines and therapies leads to adverse effects on the CF patient’s psychosocial status, perpetuating non-adherence.6,7 Multiple studies demonstrated that age is inversely linked to adherence and that nonadherence peaks around 16 years old.8,9 Due to the progressive nature of CF, disease severity usually worsens as the child transitions to adolescence. The health benefits of daily therapies usually provide positive reinforcement, but this effect diminishes with disease advances and intensive regimen complexity.

It is difficult to accurately and objectively measure adherence to CF therapies. Thirty-five percent of CF centers do not assess medication adherence at every visit, and when the assessment is done, it is based on patient interview.10 Self-report of adherence is subject to over estimation therefore, electronic monitoring is considered the gold standard.11 Objective electronic monitoring technologies, such as electronic pharmacy records, cell phone applications, smart devices, and the iNeb are starting to emerge to assess adherence.12,10 Quittner et al.13 exposed the consequences of nonadherence on healthcare use and cost. Patients with lower pulmonary medication adherence have more exacerbations that require emergency room visits, hospitalizations, and intravenous antibiotics. Health outcomes in CF are dependent on the patient’s dedication to their therapeutic regimen. The 2014 update of the European Cystic Fibrosis Society’s (ECFS) best practice guidelines for CF care stated that improving adherence is essential for slowing the progression of disease. According to the ECFS, CF care teams can address non-adherence by encouraging patients to complete treatments and identify individual adherence barriers.1

Previous systematic reviews of non-adherence in adolescents with cystic fibrosis

Two recent systematic reviews investigated the obstacles and experiences that impact chronically ill adolescents and adherence to therapeutic regimens.14,15 Hanghoj & Boisen14 surveyed 28 studies with chronically ill adolescents and their perceived barriers to medication adherence. Chronic diseases included in the review varied in complexity and burden; however, the self-reported barriers to adherence were similar among all chronic illnesses. They concluded that the most common obstacles were current physical well-being; coincidental forgetting; normality needs and peer influences (including stigma, embarrassment); and family dynamics (dysfunction, desire for autonomy, conflict).14 The authors only included one study with a population of adolescents with a CF diagnosis, and CF treatment demands exceed most chronic diseases in the review.

In a qualitative systematic review, Jamieson et al.15 assessed the experiences among youth with CF that contribute to nonadherence and a lower quality of life. The significant themes extracted from 43 articles included were as follows: social isolation, falling behind on schoolwork, self-consciousness, time limitations, resentment of chronic treatments, and powerlessness. This study lacked a clear distinction between different age brackets and failed to specify barriers specific to the patients at highest risk for nonadherence: adolescents. Qualitative data is valuable for research on adherence and compliance, but thematic extrapolation is subject to bias. The review offers insight into the emotional vulnerabilities and challenges that contribute to a reduced quality of life in pediatrics patients with CF. The current literature lacks a thorough review of all factors, actual or perceived, that contribute to alarmingly low rates of adherence to CF therapies in adolescents, the group at highest risk.

Adherence is influenced by a multitude of variables, some of which serve as facilitators and others that act as barriers. As the identities of these variables emerge in research, it is critical for the CF team to develop strategies for monitoring and improving adherence in adolescents. Establishing healthy self-care behaviors in CF adolescent patients promotes a more successful transition to adult care and enhances disease prognosis.16 The primary objective of this review is to assess the physical, social and psychological factors that affect adherence to treatment in adolescents with cystic fibrosis. Using information from studies from 2009 to 2014, we aim to summarize unique characteristics and struggles of adolescents with CF and suggest plausible implementations for providers that can improve compliance and quality of life for these patients.

This review was conducted according to the guidelines of the Cochrane Collaboration described in the PRISMA statement updated and published in 2009.17

Eligibility criteria

A study was included in this review if it met the following inclusion criteria:

Studies were excluded if they were qualitative; if they were commentaries, reviews, letters, or case reports; if they focused only on children or adults with CF, or were conducted with caregivers only; were written in a non-English language; or if they included other chronically ill adolescents.

Search strategy

We conducted a comprehensive literature search in PubMed, Web of Science and Google Scholar. We used the following search terms and keywords for searching PubMed: (medication adherence or treatment adherence) and (adolescents, teens, teenagers) and (cystic fibrosis). We restricted the date from 1/1/2009 to present in order to capture the most up to date recommended therapies for adolescent CF patients. The electronic databases were last searched October 30, 2014.

Study selection and review procedures

EndNote X7 was used to manage all citations. Independently, EKO and RMJ reviewed and screened all citations identified by the searches by title and abstract. Full text articles were obtained for potentially eligible studies and reviewed by EKO and RMJ for final inclusion based on criteria mentioned earlier. Disagreement was handled by discussion and consensus opinion.

Data extraction

The information that was extracted from each study included reference information (author, year); country; the study population including sample size, age, gender, and ethnicity (SAGE); the study purpose/aim; the study design and type of methodological analyses utilized; study outcome, and clinical implications for improving adherence in adolescent patients with CF.

Methodological quality

The methodological quality of the studies was assessed independently by EKO and RMJ according to the criteria questions from the RTI Revised Item Bank for Bias in Observational Studies as developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.18 The list, pictured in Box 1, includes 13 items for identifying potential sources of bias, which include: selection bias (3 items), performance bias (1 item), detection bias (2 items), attrition bias (2 items), selective outcome reporting (2 items), confounding variables (2 items), and overall assessment (1 item).

|

Item # |

Criteria questions |

Type of bias assessed |

|

1 |

Do the inclusion/exclusion criteria vary across the comparison groups of the study? |

Selection bias |

|

2 |

Does the strategy for recruiting participants into the study differ across groups? |

Selection bias confounding |

|

3 |

Is the selection of the comparison group inappropriate? |

Selection bias confounding |

|

4 |

Does the study fail to account for important variations in the execution of the study from the proposed protocol? |

Performance bias |

|

5 |

Was the assessor not blinded to the outcome, exposure, or intervention status of the participants? |

Detection bias |

|

6 |

Were valid and reliable measures not used or not implemented consistently across all study participants to assess inclusion/exclusion criteria, intervention/exposure outcomes, participant benefits and harms, and potential confounders? |

Detection bias confounding |

|

7 |

Was the length of follow up different across study groups? |

Attrition bias |

|

8 |

In cases of missing data (e.g., overall or differential loss to follow up for cohort studies or missing exposure data for case-control studies), was the impact not assessed (e.g., through sensitivity analysis or other adjustment method)? |

Attrition bias |

|

9 |

Are any important primary outcomes missing from the results? |

Selective outcome reporting |

|

10 |

Are any important harms or adverse events that may be a consequence of the intervention/exposure missing from the results? |

Selective outcome reporting |

|

11 |

Did the study fail to balance the allocation between the groups or match groups (e.g., through stratification, matching, propensity scores)? |

Confounding |

|

12 |

Were important confounding variables not taken into account in the design and/or analysis (e.g., through matching, stratification, interaction terms, multivariate analysis, or other statistical adjustment such as instrumental variables)? |

Confounding |

|

13 |

Are results believable taking study limitations into consideration? |

Overall assessment |

Box 1 Item bank for bias in observational studies.

Note. From “Assessing Risk of Bias and Confounding in Observational Studies of Interventions or Exposures: Further Development of the RTI Item Bank” by M. Viswanathan, N. D. Berkman, D. M. Dryden, & L. Hartling, 2013, Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US).

Each criterion was scored with ‘yes’, ‘no’ or ‘unclear’. ‘No’ indicates that the criteria have been met and suggest a low risk of bias, and therefore, suggest high methodological quality. ‘Yes’ or ‘unclear’ suggest the potential for high risk of bias, and therefore, suggest low methodological quality. If 6 or more criteria were marked ‘no’, then the study was considered high methodological quality. If less than 6 criteria were marked as ‘yes’, then the study was deemed low methodological quality. Any disagreements between the reviewers were resolved through discussion.

Classification of study outcomes

The barriers to treatment adherence fell into three categories: psychological, physical and social. Any factor that was considered a barrier or impacted the adolescent’s adherence required statistical significance (p<0.05) in the context of the study. Using the results of studies, we established possible clinical implications for each category and suggest future research.

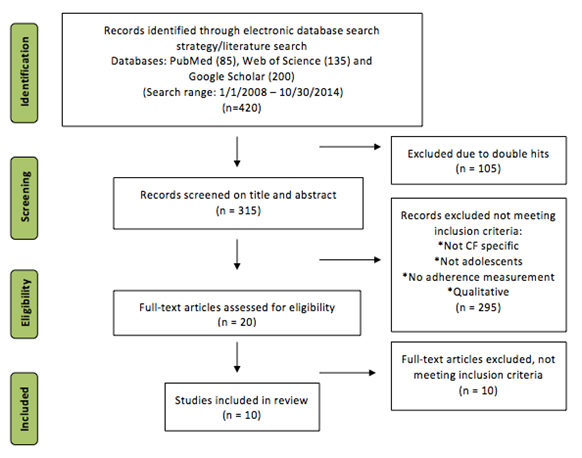

A total of 420 hits, 315 of which were unique, resulted from the initial electronic database searches. After screening the title and abstract, 295 of the studies were excluded because they were not specific to cystic fibrosis, included age categories outside of adolescence, did not analyze treatment adherence and/or challenges to adherence or were qualitative in nature. Of the remaining 20 records, the full text was obtained and assessed for inclusion for review. Ten more studies were excluded based on poor sample size, use of qualitative methods for analysis, or because they included only adults or children (or mean age under 11 years old). Finally, a total of 10 studies were agreed upon and met all inclusion criteria (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Flowchart of study retrieval.

Note. Adapted From “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses: The PRISMA Statement,” by D. Moher, A. Liberati, J. Tetzlaff, D. G. Altman, & the PRISMA Group, 2009,Annals of Internal Medicine, 151(4), p. 267. Copyright 2009 by Moher et al. Unrestricted use permitted.

Description of studies

Table 1 is a detailed review of the 10 included studies. The combined sample size is 512 adolescents with CF. The research subject’s age range varied, but means age was between 12.0 and 19.3 years old. The smallest sample size was 19 participants while the largest was 95. Six studies included adolescents’ caregivers in order to obtain more information on the patients’ adherence to CF therapies.19-24 Three studies did not take place in the United States and included participants from the United Kingdom, Denmark and Australia.25,21,26 Ten studies were observational, and therefore, analyzed quantitative data. Four studies used a cross sectional approach, primarily by means of administering a questionnaire.19,22,25,27 One study used retrospective analysis from the previous 12 months to obtain adherence data26 while another study used a prospective design to collect adherence and associated data for 7 days.28 Four studies used mixed methods design and obtained their data in a variety of modalities.19,21,23,24

|

Reference .author and year |

Country |

SAGE |

Purpose |

Study design and |

|

|

|

Ball et al. 2013 .26 |

United Kingdom |

24 participants

|

To determine weekday/ weekend and school/holiday adherence to inhaled nebulizer treatment in adolescents with CF |

Observational retrospective study |

Ÿ Significantly greater adherence during weekdays (67%, P = 0.001) and school year (66%, P < 0.001) |

Ÿ Review the importance of adherence around holidays and/or increase therapies leading up to holidays |

|

Blackwell & Quittner 2014 .28 |

United States |

95 participants |

Ÿ To measure the prevalence, intensity, frequency and location of pain, evaluate how patients cope with pain |

Observational prospective study |

Ÿ Adolescents report frequent, but relatively mild, pain |

Ÿ By understanding pain triggers, providers can target their adherence interventions at supporting their patient’s need for pain management |

|

Bregnballe et al. 2011 .21 |

Denmark |

88 participants (CF patients) and 161 caregivers |

To explore barriers to treatment perceived by adolescents with cystic fibrosis and their caregivers |

Observational mixed methods study |

Ÿ Adolescents and parents are in agreement regarding most common barriers, which are lack of time, forgetfulness and unwillingness to take medication in public |

Ÿ The atmosphere within the family may shape adolescent patient’s perception of barriers to adherence and their level of adherence |

|

Bucks et al. 2009 .25 |

Australia and United Kingdom |

38 participants |

To explore whether the personal model of illness held by adolescents with CF is associated with their use of three principle forms of treatment: chest physiotherapy (CPT), pancreatic enzyme supplements (ES) and nebulized antibiotics |

Observational cross-sectional design |

Ÿ Older adolescents were more likely to agree they would have CF the rest of their life, fewer negative emotions about illness, less likely to think CPT was necessary and had fewer concerns about adherence to enzyme supplementation |

Ÿ The Self-Regulation Model may be useful framework to explore adherence |

|

Dziuban et al. 2010 .27 |

United States |

60 participants |

To identify the barriers to treatment adherence and attitudinal patterns in adolescents by exploring the effects of: |

Observational cross-sectional design |

Ÿ Adolescents report that the treatment most acceptable to miss is airway clearance (vest) and that the treatment least acceptable to miss is inhaled tobramycin (antibiotic) |

Ÿ Target future adherence interventions on condensing treatment time and combining therapies |

|

Everhart et al. 2014 .23 |

United States |

19 participants + caregivers |

Ÿ To determine the level of family functioning among families with an adolescent child with CF |

Observational mixed methods study |

Ÿ All families scored in unhealthy range of MICS scoring except for the Roles subscale suggesting that families with a child with CF are more task orientated at mealtime at the expense of more emotional and interpersonal interaction |

Ÿ Family functioning may improve as child ages and matures |

|

Helms, Dellon & Prinstein 2014 .24

|

United States |

42 participants + caregivers |

Ÿ To examine friendship quality in adolescents with CF and the association with treatment adherence, HRQOL and health status |

Observational mixed methods study |

Ÿ Adolescents with CF have fewer friendships with other people with CF (P < 0.001) and less interaction with friends with CF (if they even have a friend with CF) (P < 0.01) |

Ÿ The study suggests that there is no clear indication that friendship dynamics actually have an effect on treatment adherence goals, however, clinicians should be aware of the social needs of their patients |

|

Simon et al. 2011 .22 |

United States |

54 participants + caregivers |

To examine the relationship between body satisfaction, nutritional intake and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in male and female adolescents with CF |

Observational cross-sectional design |

Ÿ Poor body image, especially in females, is associated with lower caloric intake (even in patients with below guideline-recommended BMIs) |

Ÿ Nutritional adherence could be improved by focusing on improving body image |

|

Smith et al. 2010 .20 |

United States |

39 Participants + caregivers

|

Ÿ To determine the rate of depressive symptoms in patients and caregivers |

Observational mixed methods study |

Ÿ Adolescents with CF and their caregivers report higher rates of depressive symptoms than general population |

Ÿ Screen for depression in patients with CF and their caregivers annually and refer for a more comprehensive family assessment accordingly |

|

White et al. 2009 .19 |

United States |

53 participants + caregivers |

To determine the rates of psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents with CF and to explore the relationship between psychopathology and family function on adherence rates |

Observational cross-sectional design |

Ÿ 57% of children met criteria for at least one psychiatric diagnosis, with 34% with more than one diagnosis; no control group used |

Ÿ Evaluate patients for presence of psychiatric disorder and how it may affect adherence |

|

Barker et al. 2012 |

USA |

11 – 18 years (mean = 15.73) |

|

Semi-structured interview – list social support network, closeness, person’s awareness of CF and then supportive and non-supportive behaviors the person exhibits |

- Treatment related – reminders, helping with them, monitor |

|

Table 1 Review of the literature from 2009 – 2014: summaries of studies (in alphabetical order).

Adherence was measured through an array of methods including electronic inhaled medication device to record data.26 Medication Possession Ratio (MPR) from pharmacy refill records28 reported questionnaires or recall methods developed by the authors.27,22,20,21 Medication Adherence Report Scale (MARS).25 Treatment Adherence Rating Scale (TARS),23 Treatment Adherence Questionnaire-Cystic Fibrosis (TAQ-CF)24 and Confidential Cystic Fibrosis Management Profile (CCFMP).19 The adherence barriers of interest varied across the studies including the schedule/day of the week26 pain associated with treatments in CF28 family dynamics21,23 patient’s perception of their own illness25,27 peers focused24. body image22 depressive symptoms20 and co-morbid psychiatric disorders.19 Various types of pre-existing questionnaires with proven reliability and validity were used to assess other parameters of interest such as the quality of life, psychosocial behaviors, and psychosocial symptoms.

Methodological quality of included studies

The methodological quality (risk of bias) of the 10 studies included in this review was assessed. Five studies were classified as high quality, with low risk for bias, and five studies were classified as low quality, with high or unclear risk for bias (Table 2).

|

Study |

Type of Bias |

Overall Methodological Quality |

|

Ball et al., 2013 |

A2, A19, B4, C6, E11, E12,G13 |

Low |

|

Blackwell & Quittner, 2014 |

D8 |

High |

|

Bregnballe et al., 2011 |

A3, B4, C6, D8, E12, G13 |

Low |

|

Bucks et al., 2009 |

A1, A3 , B4, C6, E12, G13 |

Low |

|

Dziuban et al., 2010 |

A2, C6 |

High |

|

Everhart et al., 2014 |

A3, A19, C5, C6, D8, G13 |

Low |

|

Helms et al., 2014 |

A2, C6, E12 |

High |

|

Simon et al., 2011 |

E11 |

High |

|

Smith et al., 2010 |

C5, D7, E12 |

High |

|

White et al., 2008 |

A3, C6, D8, E6, E12, G13 |

Low |

Table 2 Methodological quality of included studies.

Note. If 6 or more criteria from RTI item bank (Box 1) were marked ‘yes’, then the study was considered low methodological quality. If less than 6 criteria from RTI item bank (Box 1) were marked as ‘yes’, then the study was deemed high methodological quality.

A = Selection bias (A1, A2, A3,)

A1 = Selection outcome reporting (A19, A110)

B = Performance bias (B4)

C = Detection bias (C5, C6, C11, C12)

D = Attrition bias (D7, D8)

E = Confounding (E6, E11, E12)

F = Selective outcome reporting (F9, F10)

G = Overall assessment (G13)

Hindrances to adherence in adolescents with cystic fibrosis

The synthesis of the study data was classified into three main categories of barriers to adherence, including subclasses:

Table 3 summarizes the categories of the barriers to adherence, the specific barrier to adherence, and the methodological quality of the study.

|

Study |

Category |

Specific barrier |

Study quality |

|

Simon et al.22 |

Psychological |

Body image |

High |

|

Bucks et al.25 |

Psychological |

Perception of disease |

Low |

|

Smith et al.20 |

Psychological, Social |

Internalizing disorders, Family dynamics |

High |

|

White et al.19 |

Psychological, Social |

Internalizing disorders, Family dynamics |

Low |

|

Dziuban et al.27 |

Psychological, Social |

Perception of disease, Family dynamics |

High |

|

Everhart et al.23 |

Social |

Family dynamics |

Low |

|

Helms et al.24 |

Social |

Friendship quality |

High |

|

Ball et al.26 |

Physical |

Schedule |

Low |

|

Bregnballe et al.21 |

Physical |

Time management |

Low |

|

Blackwell & Quittner28 |

Physical |

Pain |

High |

Table 3 Classification of barriers to treatment adherence.

Note: Multiple studies were classified as more than one category.

Psychological barriers

Body image: Psychological factors play an integral role in adherence in adolescents with CF. Living with CF is cumbersome for both the adolescent and their caregivers. Adherence is heavily influenced by adolescents’ capacity to cope with both the stresses of adolescence and management of a chronic disease. Simon et al.22 reported that poor body image in teenage females is associated with lower caloric intake, even with a low BMI. Females were significantly more likely have a poorer physical health-related quality of life than their male counter parts. On the contrary, the males desired to be heavier with more muscle mass, and their nutritional recommendations were more likely to be followed.22

Internalizing disorders: Adolescents with CF and their caregivers reported higher rates of depressive symptoms than the general population, and significant negative associations between depressive symptoms and adherence to treatment.20 White et al.19 examined the rates of psychiatric diagnoses in adolescents with CF. The results indicated that 57% of the patients met Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) criteria for at least one psychiatric diagnosis, primarily an internalizing disorder such as depression or anxiety. While the presence of a psychiatric diagnosis did not exhibit a statistically significant effect on measured adherence rates, the patients with anxiety disorders reported higher adherence to treatment.

Perception of disease: An adolescent’s personal model of illness including perceptions of the efficacy, necessity of treatment, and current health status concerns is associated with medication use and adherence. Bucks et al.25 demonstrated that if the adolescent accepts CF as a permanent and chronic disease and believes in the usefulness of a specific treatment, then they have better adherence to that treatment. The older participants were more likely to agree that they would have CF for the rest of their life, had fewer negative emotions about the illness, were less likely follow chest physiotherapy recommendations, and enzyme supplementation guidelines.25 Dziuban et al.27 examined the relationship between attitudinal patterns and adherence and found that the subjectively less healthy group was more likely to agree with the following statements: “having to follow the treatments for cystic fibrosis means I have less freedom in my life,” “my primary team does not fully understand how difficult it is for me to follow the treatments,” and “I have trouble sticking to my treatments when I have no physical symptoms”.

Physical barriers

Schedule: One follow-up study demonstrated that children with CF demonstrate greater adherence to therapies in the evening rather than the morning.29 Adolescents’ average weekday adherence was significantly greater than weekend adherence, and their average adherence on school days was greater than over the holidays, suggesting that having a structured schedule improves adherence.26

Time management: Bregnballe et al.21 determined that both the adolescent and their caregivers reported the primary barrier to adherence was lack of time. Adolescents with poor adherence often report issues with time management centered around forgetting treatments, being too busy, and having too many treatments to manage.27

Pain: Adolescents report that pain and discomfort contribute to poor treatment adherence. Blackwell & Quittner.28 showed that adolescents with CF have significant, but mildly intense pain all the time and the location of the pain is most commonly in their stomach, head/neck and chest. Adolescents rated pain associated with treatments as significantly more intense than general pain, and that airway clearance therapies cause the most pain and discomfort.

Social barriers

Family dynamics: White et al.19 determined that families with higher levels of cohesion were significantly associated with higher rates of youth and parent-reported adherence, and a reduction in the number of missed treatments per child. Smith et al.20 showed that adolescents who were insecurely related to either parent had significantly more depressive symptoms than securely related adolescents, resulting in a decrease in adherence to airway clearance therapies. Secure relatedness was measured by the child’s desire to be near the parent and the positive and negative emotions the child feels in the presence of the parent. Secure relatedness with caregivers was associated with good adherence. In contrast, Smith et al.20 showed the caregivers’ depressive symptoms were associated with better adherence.

Everhart et al.23 used the Mealtime Interaction Coding System (MICS) to assess family function at mealtime with a child with CF. They found that all the families included in the study scored in the unhealthy range except for the Roles subscale, which suggests that families may be more task orientated at mealtime at the expense of more emotional and interpersonal interactions. Better scores on family function were associated with worse scores on pancreatic enzyme adherence and better scores on antibiotic adherence. Adolescents who reported a higher number of barriers to adherence also report more arguments with caregivers and less feelings of family support.21

Friendship quality: Helms et al.24 revealed that higher positive friendship qualities were associated with lower treatment adherence levels, most likely due to the amount of time spent with peers; however, adolescents with positive friendships also reported a higher quality of life, despite the lack of adherence. A major challenge for CF adolescents centers on infection control policies, which discourage CF patients from spending time in person with one another.7 Despite the psychosocial benefits of having friends with CF, adolescents reported fewer friendships, fewer interactions with friends with CF, and reported that their best friend is someone without CF.24

The findings in this review highlight three major areas of personal wellness that contribute to treatment adherence of adolescents with cystic fibrosis: psychological, physical and social. Disruptions in any of these areas create barriers to achieving optimal adherence (Figure 2). Accurate identification of the problematic area(s) is the initial step in breaking down the barriers to adherence. This review provides insight into the contributory factors to treatment noncompliance in adolescent patients with CF. Despite the low methodological quality of five of the 10 studies included, all 10 studies acknowledged the key relationship between adherence and a potential or actual obstacle in the adolescent’s life.

Figure 2 Targets for Interventions for Treatment Nonadherence in Adolescents with CF.

Note. Disturbances in any of these areas impedes optimal adherence in adolescents with CF. Each dimension has the potential to affect the other two.

Psychological support is recognized as a key component of CF management for both the patient and caregivers. The updated ECSF best practice guidelines included a large section on psychosocial support, which should be prioritized and incorporated into the medical management of CF patients.1 Adolescence is a time when their bodies are changing promoting heightened awareness of how they are perceived by peers. A negative body image and decreased self-esteem contributes to nonadherence in teens with CF.22,6 CF affects multiple body systems and results in overt symptoms, such as chronic coughing, short stature, steatorrhea, causing distress and embarrassment.30 Differences from their peers may predispose the teen to develop anxiety and depression. While prevalence rates vary, the rates of depression are higher in adolescents with CF than the general population.31,20 Co-morbid psychiatric conditions such as depression or oppositional disorders are associated with poor adherence.6 The association between depression and worse adherence demonstrated across many chronic diseases and suggests the important of routine screening for mental health disorders. The adolescent with CF and anxiety disorders reported significantly higher rates of adherence, although it is not clear if their anxiety actually influenced their compliance to daily treatments or created a tendency to over report.19 Regardless, if a co-morbid psychiatric disorder exists and is negatively contributing to the adolescents’ quality of life and well-being, then screening, detection, and management of mental health disorders must be a priority in these patients.

Our review showed that an adolescent’s perception of their illness and their belief in the efficacy of treatment impacts adherence. An adolescent who recognizes the health threat posed by nonadherence, and appreciates the necessity of the assigned therapies has better adherence and health outcomes.25 The relationship and level of trust between the CF care team and the adolescent is crucial in establishing effective communication. Adolescents who perceived themselves as less healthy are more likely to have maladaptive attitudes about CF, including freedom restriction, and difficulties with adherence during times of relatively good health.27 Motivational interviewing may promote self-care behaviors.8 Self-management education, a type of intervention that equips patients and families with the knowledge, confidence, and skills necessary to manage their illness has not demonstrated significant long-term effects on adherence; however, this is an area that warrants more research as studies have demonstrated that it increases knowledge of disease and treatments in the short-term.32

The physical demands of CF therapies are strenuous and uncomfortable. Airway clearance, an aspect of CF management with notoriously low adherence rates, causes the most pain and discomfort.28 There is a high prevalence of pain in adolescents and it appears to interfere with treatment adherence, as well as the patient’s overall functioning. Identifying pain triggers and adequate management of pain can help providers tailor treatment regimens for each patient.

Structured schedules with an established treatment routine facilitates adherence. Adolescents with CF value time as they become more aware of their shortened life expectancy.15 Adolescents have higher rates of adherence on school days and in the evenings, whereas adherence decreases during the holidays and on weekends.29,26 Balancing the time between treatments, educational, social, and personal commitments remain an ongoing challenge for CF care teams as forgetfulness and being busy are common excuses for missed treatments.27,21 Electronic reminders and improvements in technology may be useful for adolescents as they become more independent with their self-care.12,2

Adolescents have higher rates of adherence with the support of a positive social network. A positive family dynamic and healthy caregiver relationship is associated with good adherence.11 The burden of CF weighs heavily on caregivers and has a significant impact on family function and cohesion. Caregivers of children with CF have higher rates of depression than those of healthy children; however, the effect on adherence remains unclear.20 Adolescents with unstable family dynamics are less likely to be ready for the transition to independent self-management.16 During adolescence, friends become the primary social support for treatments and parents have less influence on their disease management. Barker et al.5 reported that only 58% of CF adolescents had informed everyone in their support group about their disease. The lack of awareness within a peer group may create scheduling conflicts and result in reduced adherence around peers. Positive friendships improve the quality of life, but also decrease commitment to treatments.24 Encouraging adolescents to be open about their diagnosis allows for the peers to engage in supportive behaviors such as treatment reminders, encouragement, and assistance with the treatments.5

Limitations

The sample sizes of studies included in the review were small. This review focuses on a specific age bracket, further narrowing the search and potential sample sizes. With this limitation it is difficult to achieve statistical significance and many studies reported trends and associations, rather than statistically significant correlations or effects. Due to the progressive nature of CF, there are not many studies on adolescents with the disease. As longevity improves, the data is expected to continue to expand. In many circumstances, researchers must rely on convenience sampling for these types of studies. Many studies lack longitudinal data on adherence trends, which makes it difficult to accurately identify true barriers to adherence. The studies in this review were focused on identifying barriers rather than testing interventions to improve adherence in this age group.

The inconsistency of adherence measurement tools does not allow for cross study comparisons. The majority of studies looked at adherence at one time point or during a short term period, rather than long term patterns, which would have more of an effect on health outcomes. Adherence is typically self-reported, which increases the risk for over or under estimation. Objective measurement tools for adherence are critical for future studies on adherence and for integration into clinical practice.

There is a significant need for high quality studies in the literature on interventions to improve adherence. The most common limitation is a small sample size and lack of a standardized way to measure adherence and health outcomes. The studies in this review include reliable and validated tools used for assessing various dimensions of health, such as the CF-HRQOL tool.

A high quality relationship between the CF health care team and the patient opens up communication and allows for the personalization of disease management. Assessing the patient’s regimen annually and identifying strengths and weaknesses may improve long-term adherence.2 As new treatments emerge, team members should seek opportunities to simplify the regimen while maintaining effectiveness. Psychological screening tools should be used for both adolescents and caregivers annually and psychological stressors should be addressed at every single visit.11 Parents with a stronger locus of internal control have improved psychological health and often use prayer to empower themselves to take care of their child.33 Encouraging families and patients to explore how faith and spirituality impact their ability to cope is another way to improve adherence.

It is important for providers to spend one on one time with adolescents during clinic visits to strengthen rapport and embolden the adolescent toward independent. The provider should address anticipatory guidance issues for general adolescence, as well as review how lifestyle changes will affect their treatment regimen. It is especially important to go over the importance of each therapy near the holidays or periods of vacation. Using motivational interviewing techniques, provide may help the patient explore ways to improve adherence to therapies. Many providers only confront patients about adherence when the lung function is reduced or they are sick, which can be viewed as confrontational rather than educational.10 Using technology, such as secure text messages through secure servers, is an area of provider-patient communication that can be developed to improve access to the CF team and treatment reminders. If the patients believe the treatments are essential and beneficial, they are more likely to prioritize those treatments.34 The provider can help set small, realistic goals in the context of the patient’s lifestyle to allow them to feel confident and less resistant to change.8

Barker et al.5 demonstrated that family tends to provide more tangible support while friends tend to offer more emotional support. Assessing the family dynamic and characteristics of their peer group allows the provider to recognize adherence problem areas and intervene accordingly.35

Educational opportunities

Adolescent care curriculums should include information regarding the management of adolescents with chronic illnesses. Nonadherence has a significant impact on the adolescent’s long-term health outcomes. Primary care providers should deliver appropriate counseling, track compliance, and develop personalized interventions to prevent adverse long-term effects of non-adherence.10

Future research

The research on treatment adherence in this population is limited to studies with low levels of clinical evidence, and therefore, low statistical power. The measurement of adherence, whether it is subjective or objective, requires standardization in order to improve the quality of data. Due to the inconsistencies in data collection, there are insufficient high quality research studies in the literature, such as randomized control trials. Larger sample sizes can be attained through the collaboration of CF care centers nationally and internationally to expand recruitment reach and standardize data collection. By including an age, race and gender-matched control group of adolescents, researchers can find out more about the crucial physical, psychological, and social differences in adolescents with CF. Further research focusing on adherence with adolescents with CF will promote evidence-based practice.

Non-adherence in chronically ill adolescents has become a public health concern and, therefore, is an area that should be targeted for future high quality improvement research.14 The articles included in this systematic review identified noteworthy barriers that adolescents with CF encounter as they strive towards independent self-management. There are psychological, physical and social obstacles that contribute to nonadherence and will serve as targets in future interventions that aim to improve upon adolescents’ commitment to their daily therapies. A multidisciplinary approach may be useful as challenges to adherence are present in several areas of patient’s lives.

None.

The authors disclose no conflicts of interest.

©2016 Owen, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.