Journal of

eISSN: 2373-4426

Review Article Volume 13 Issue 3

Mother and Child Department of the Faculty of Medicine, University of Parakou, Benin

Correspondence: Noudamadjo Alphonse, Mother and Child Department of the Faculty of Medicine -University of Parakou, Parakou, Borgou, Benin, Tel (229) 90049007, 94794149

Received: August 07, 2023 | Published: November 1, 2023

Citation: Noudamadjo A, Agbeille MF, Kpanidja MG, et al. Nutritional profile of hospitalized children aged 1 to 59 months in the pediatric department of the CHU of Parakou from 2018 to 2020. J Pediatr Neonatal Care. 2023;13(3):201-206. DOI: 10.15406/jpnc.2023.13.00517

Introduction: Malnutrition remains a public health problem affecting especially children. The objective of this study was to describe the nutritional profile of hospitalized children aged 1 to 59 months in the pediatric department of the teaching hospital (CHU) of Parakou in Benin from 2018 to 2020.

Framework and method: This was a descriptive study with retrospective data collection. Data were collected from the medical records of children aged 1 to 59 months, admitted to the pediatric department of the CHU of Parakou from January 1, 2018 to December 31, 2020. Epi data 3.1 fr, Microsoft Excel 2016 and Epi Info version 7.2 softwares were used to describe variable.

The research protocol was submitted to the local ethics committee of the University of Parakou and obtained its approval under the reference: 0540/CLERB-UP/P/SP/R/SA

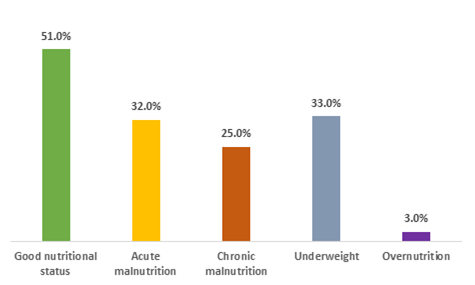

Results: A total of 6789 children met the inclusion criteria out of 9285 children admitted during the study period. 3433 children had a good nutritional status, representing a frequency of 51.0%. Children were suffering from acute malnutrition (wasting), chronic malnutrition (stunting) and underweight in 32.0%, 25.0% and 33.0% of cases, respectively. The frequency of over nutrition was 3.0%.

Conclusion: The frequency of pathological nutritional status, especially undernutrition is high in the pediatric department of the CHU of Parakou. Community actions are necessary to reverse this trend.

Keywords: nutritional profile, hospitalized children, Benin

Infant and child mortality remains high in sub-Saharan Africa despite the efforts made by States in the context of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).1

According to the fifth Demographic and Health Survey in Benin (DHSB-V),2 this mortality was 9.6%.

Malnutrition is one of the main causes of infant and child mortality in Africa.3

It is directly or indirectly associated with the death of children under 5 in 45% of cases,4 underlining its importance in infant-child morbidity and mortality.

Globally, according to UNICEF in 2018,4 21.9% of children suffered from stunting and 7.3% from wasting.

According to Massen et al,5 in Algeria, the prevalence of malnutrition, acute malnutrition (wasting) and chronic malnutrition (stunting) was 23.55%, 13.45% and 10.2%, respectively.

In West and Central Africa, according to UNICEF in 2018,4 growth retardation and emaciation affected 33.1% and 9% of children, respectively.

In Benin, according to the DHS-V,2 stunting, wasting and underweight affected 32%, 5% and 17% of children under five years of age, respectively.

The objective of this study was to describe the nutritional profile in hospitalized children aged 1 to 59 months in the pediatric department of the teaching hospital (CHU) of Parakou from 2018 to 2020 in order to planify the management of cases.

Framework, type and period of study

This was a descriptive cross-sectional study with retrospective data collection, conducted in the pediatric department (child sector) of the CHU of Parakou in Benin Republic. The data were collected from the medical records of children admitted from January 1, 2018 to December 31, 2020.

Study population

The target population was represented by hospitalized children aged 1 to 59 months in the department.

The source population consisted of hospitalized children aged 1 to 59 months in the pediatric department of the CHU of Parakou, admitted during the study period.

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows:

Exclusion criteria

Information that could interfere with the diagnosis of undernutrition or over nutrition (cases of nephropathy, heart disease, liver disease or any other situation with symmetrical edema).

Sampling

This was an exhaustive and consecutive census of the medical records of hospitalized children aged 1 to 59 months during the study period.

Study variables

The main variable was the nutritional status including three subclasses namely: a good nutritional status, a poor nutritional status (undernutrition) and an excess of nutritional status (over nutrition).

The nutritional status is good when the following anthropometric parameters and indices are all normal:6

Undernutrition included acute malnutrition (wasting), chronic malnutrition (stunting) and underweight.6

Over nutrition includes overweight and obesity:6

The secondary variables were socio-demographic (age of the child, sex, socio-professional status of the parents); clinical (mode of admission, reason for consultation, anthropometric parameters on admission, diagnosis, vaccination); nutritional (exclusive breastfeeding, food diversification) and evolutionary (vital status at hospital discharge).

Regarding food diversification, which is a nominal qualitative variable, it included three categories (Good, Bad and not specified). Food diversification was of good quality if and only if the following seven (07) conditions were met:

Diagnosis

A qualitative nominal variable, representing the child's health problem. The health problems were grouped into five diagnoses: severe malaria, sepsis, acute respiratory tract infections, gastro-intestinal tract infections with diarrhea and other diagnoses. The diagnoses were retained as notified in the medical records.

Vital status at hospital discharge

Qualitative dichotomous variable corresponding to the state of the child’s health at discharge and has two categories: Alive and Deceased.

Method and process of data collection

Data collection was carried out using a survey form, the medical record of each child, and hospitalization registers. From the hospitalization registers, all medical records of children aged 1 to 59 months that met the inclusion criteria were identified using the medical records and the survey forms were filled.

Data processing

The data collected were entered into Epi Data 3.1fr software. After the entry, the consistency of data and eventual entry errors were checked. Then these data were exported into Microsoft Excel 2016 software for analysis. The analysis was also done with Epi Info version 7.2. The parameters of central tendencies (Mode, Mean, and Median) and dispersions (Standard Deviation) were used for the description of the quantitative variables. Proportions with confidence intervals were used for qualitative variables.

Ethical considerations

The data were collected and processed with respect for anonymity and confidentiality. The research protocol was submitted to the local ethics committee of the University of Parakou and obtained its approval under the reference: 0540/CLERB-UP/P/SP/R/SA.

A total of 9285 children aged 1 to 59 months were admitted to the pediatric department during the study period. 7204, 6789 and 415 of them were included, studied and excluded, respectively.

Among the 415 (4.47%) children excluded, 99 (1.07%) were aged 1 to 5 months and 316 (3.40%) aged 6 to 59 months. The diagnoses made in the children excluded from the study were: heart failure (126 cases), nephrotic syndrome (96 cases), acute renal failure (75 cases), acute glomerulonephritis (58 cases) and hepatic failure (29 cases).

Sociodemographic, clinical and evolutionary characteristics of children

1) Sex

Boys were the most represented (54.4%). The sex ratio was 1.2%.

2)Age

The average age of the children was 21.5 ± 13.4 months with the extremes of 1 and 59 months. 549 (8.09%), 6240 (91.91%) and 44.7% of children were 1 to 5 months, 6 to 59 months and 24 to 59 months old, respectively (Table 1).

|

Size |

% |

95% CI |

[1 ; 6[ |

549 |

8.1 |

[7.0- 9.2] |

[6 ; 12[ |

1400 |

20.6 |

[19.9- 21.3] |

[12 ; 24[ |

1806 |

26.6 |

[25.9- 27.2] |

[24 ; 59] |

3034 |

44.7 |

[44.2- 45.2] |

Total |

6789 |

100 |

|

Table 1 Distribution of hospitalized children aged 1 to 59 months by age groups in the pediatric department of the CHU of Parakou from 2018 to 2020

3) Children's diet

Exclusive breastfeeding up to 6 months was specified for 3452 children. The children's mothers had declared having practiced exclusive breastfeeding up to 6 months in 54.4% of cases.

The quality of complementary feeding was specified for 2881 children (42.4%). All of these 2881 children had a poor food diversification.

Nutritional profile of hospitalized children from 2018 to 2020

3433 out of 6789 children had a good nutritional status, i.e. 51.0%. The frequency of wasting, stunting, underweight and over nutrition (overweight and obesity) was 32.0%, 25.0%, 33.0% and 3.0%, respectively.

Figure 1 shows the nutritional profile of the children included in the study.

Figure 1 Distribution of hospitalized children aged 1 to 59 months according to the nutritional status in the pediatric department of the CHU of Parakou from 2018 to 2020.

Nutritional status according to anthropometric parameters and indices

Among 4701 children aged 6 to 59 months, whose MUAC had been specified, 613 (13.1%) had moderate wasting, 439 (9.3%) had the severe form (Table 2).

WH index and BMI/age were normal, greater than or equal to -2 SD in 3182 children. Among them, the diagnosis of wasting was made only on the basis of MUAC in 8.5% of cases, including 7.5% of moderate type and 1.0% of severe type (Table 2).

|

MUAC (mm) |

Size |

% |

CI (95%) |

All children included (N= 4701) |

||||

Good nutritional status |

≥125 |

3649 |

77.6 |

[77.1- 78.0] |

Moderate wasting |

[115; 125[ |

613 |

13.1 |

[12.0-14.1] |

Severe wasting |

<115 |

439 |

9.3 |

[8.0- 10.5] |

Total |

4701 |

100 |

||

Children with normal WH index and BMI/Age (n= 3182) |

||||

Good nutritional status |

≥125 |

2912 |

91.5 |

[91.0- 91.9] |

Moderate wasting |

[115; 125[ |

238 |

7.5 |

[5.8- 9.2] |

Severe wasting |

< 115 |

32 |

1 |

[0.6- 1.5] |

Total |

|

3182 |

100 |

|

Table 2 Distribution of the nutritional status according to the mid-upper arm circumference of hospitalized children aged 6 to 59 months in the pediatric department of the CHU of Parakou from 2018 to 2020

According to the WH index, 1077 children (15.9%) and 841 (12.4%) had moderate and severe wasting, respectively. The number of children with overweight and obesity according to the WH index was 98 (1.4%) and 67 (1.0%), respectively (Table 3).

2928 children had a normal MUAC (≥ 125mm) and a BMI/age greater than or equal to -2 SD. Among them, only 16 had a WH Index < -2 SD. The diagnosis of moderate wasting had therefore been made only on the basis of WH index (normal MUAC and BMI/Age) in 0.5% of cases (Table 3).

|

WH Index (SD) |

Size |

% |

CI (95%) |

All children included (N= 6789) |

||||

Obesity |

≥3 |

67 |

1 |

[0.7- 1.9] |

Overweight |

[2 ; 3[ |

98 |

1.4 |

[1.0- 2.1] |

Good nutritional status |

[-2 ; 2[ |

4706 |

69.3 |

[68.9- 69.7] |

Moderate wasting |

[-3 ; -2[ |

1077 |

15.9 |

[15.1- 16.7] |

Severe wasting |

<-3 |

841 |

12.4 |

[11.5- 13.3] |

Total |

6789 |

100 |

||

Subjects with normal MUAC and BMI/Age (n= 2928) |

||||

Obesity |

≥3 |

33 |

1.1 |

[0.5- 2.1] |

Overweight |

[2 ; 3] |

70 |

2.4 |

[1.9- 3.0] |

Good nutritional status |

[-2 ; 2[ |

2809 |

96 |

[95.5- 96.5] |

Moderate wasting |

[-3 ; -2[ |

16 |

0.5 |

[0.1- 0.9] |

Severe wasting |

<-3 |

0 |

0 |

--- |

Total |

|

2928 |

100 |

|

Table 3 Distribution of the nutritional status according to the weight-for-height index of hospitalized children aged 1 to 59 months in the pediatric department of the CHU of Parakou from 2018 to 2020

SD: Standard Deviation

According to the BMI/Age, 1111 children (16.4%) had moderate wasting and 926 (13.6%) had a severe type. According to BMI/Age, the number of children with overweight and obesity was 115 (1.7%) and 68 (1.0%), respectively (Table 4).

2987 children had a normal MUAC (≥ 125mm) and a normal WH Index (≥-2 SD). Among them, 75 had a BMI/age < -2 SD. The diagnosis of wasting was therefore made only on the basis of BMI/age in 2.5% of cases, all of moderate type (Table 4).

|

BMI/Age (SD) |

Size |

% |

CI (95%) |

All children included (N= 6789) |

||||

Obesity |

≥3 |

68 |

1 |

[0.6- 2.3] |

Overweight |

[2 ; 3[ |

115 |

1.7 |

[1.3- 2.5] |

Good nutritional status |

[-2 ; 2[ |

4569 |

67.3 |

[66.8- 67.7] |

Moderate wasting |

[-3 ; -2[ |

1111 |

16.4 |

[15.6- 17.2] |

Severe wasting |

<-3 |

926 |

13.6 |

[12.7- 14.5] |

Total |

6789 |

100 |

||

Children with normal MUAC and WH index (n= 2987) |

||||

Obesity |

≥3 |

37 |

1.2 |

[0.8- 1.9] |

Overweight |

[2 ; 3[ |

68 |

2.3 |

[1.9- 2.8] |

Good nutritional status |

[-2 ; 2[ |

2807 |

94 |

[93.5-94.5] |

Moderate wasting |

[-3 ; -2[ |

75 |

2.5 |

[2.1- 3.1] |

Severe wasting |

<-3 |

0 |

0 |

--- |

Total |

|

2987 |

100 |

|

Table 4 Distribution of the nutritional status according to the body mass index for age of hospitalized children aged 1 to 59 months in the pediatric department of the CHU of Parakou from 2018 to 2020

SD: Standard Deviation

The children in this study had chronic malnutrition (stunting) in 24.9% of cases, including 11.3% of severe type (Table 5).

|

HA Index (SD) |

Size |

% |

CI (95%) |

Good nutritional status |

≥-2 |

5097 |

75.1 |

[74.7- 75.5] |

Moderate stunting |

[-3 ; -2[ |

926 |

13.6 |

[12.7- 14.4] |

Severe stunting |

<-3 |

766 |

11.3 |

[10.3- 12.2] |

Total |

6789 |

100 |

|

|

Table 5 Distribution of the nutritional status according to the height-for-age index of hospitalized children aged 1 to 59 months in the pediatric department of the CHU of Parakou from 2018 to 2020 (n = 6789)

SD: Standard Deviation

The children in the study were underweight (UW) in 33.1% of cases, including 15.3% of severe type (Table 6).

|

WA Index (SD) |

Size |

% |

CI (95%) |

Good nutritional status |

≥-2 |

4538 |

66.9 |

[66.5- 67.3] |

Moderate UW |

[-3 ; -2[ |

1211 |

17.8 |

[17.0- 18.5] |

Severe UW |

<-3 |

1040 |

15.3 |

[14.5- 16.1] |

Total |

6789 |

100 |

|

|

Table 6 Distribution of the nutritional status according to the weight-for-age (WA) index of hospitalized children aged 1 to 59 months in the pediatric department of the CHU of Parakou from 2018 to 2020, (n = 6789)

SD: standard Deviation

Diagnosis

The most common diagnosis was severe malaria in 4386 children (64.6%) (Table 7).

|

Size |

% |

CI (95%) |

Severe malaria |

4386 |

64.6 |

[64.2- 65.0] |

Sepsis |

1005 |

14.8 |

[13.9- 15.6] |

Acute respiratory tract infections |

706 |

10.4 |

[9.4- 11.4] |

Gastro-intestinal tract infections with diarrhea |

495 |

7.3 |

[6.1- 8.5] |

Others |

197 |

2.9 |

[1.0- 4.8] |

Total |

6789 |

100 |

|

Table 7 Distribution of hospitalized children aged 1 to 59 months according to the diagnosis in the pediatric department of the CHU of Parakou from 2018 to 2020 (n = 6789)

Others: epileptic seizure (37 cases), encephalitis (27 cases), meningitis (88 cases), urinary tract infection (31 cases), nutritional rickets (5 cases), measles (17 cases), acute renal failure (22 cases).

Vital status at discharge

Among the 6789 children studied, 693 died, i.e. an intra-hospital mortality of 10.2%. The remaining 6096 children were discharged alive (89.80%).

Validity of the study

A descriptive study was carried out with retrospective data collection from January 1, 2018 to December 31, 2020, i.e. a period of 03 years.

An exhaustive and consecutive census of the medical records of hospitalized children aged 1 to 59 months during the above-mentioned period was carried out. The retrospective nature of this study led to biases related to the non-documentation or lack of precision of certain information in children's medical records.

In fact:

Despite these inherent limitations of this type of study (retrospective), this work has the merit of approaching a very large sample of hospitalized children in the pediatric department over three years, with a rigorous method respecting ethical standards and ethics. In addition, the diagnosis of pathological nutritional status was made using several complementary anthropometric parameters, making our results more objective.

Nutritional profile

The study showed that only one out of two hospitalized children had a good nutritional status. This is a worrying situation which may partly explain the high proportion of deaths in the department (10.20%). This poses the problem of children’s feeding both in the community and in the department where the management of eutrophic sick children does not systematically take into account the dietary component.

Acute malnutrition (wasting)

Among the children included, 32% had acute malnutrition. In studies carried out in sub-Saharan Africa, variable frequencies from one region to another have been reported. Thus, Milcent et al,8 in Benin in 2008 and Thiam et al,9 in Senegal in 2016 had observed similar frequencies of 33% and 32.9%, respectively. Kouamé et al,10 in Ivory Coast in 2017 and Sinanduku et al,11 in the DRC in 2020 had found higher frequencies of 55.86% and 81.2%, respectively. In Togo, Mali and Burkina Faso, Lawson-Evi et al,12 Sangho et al,13 Ouédraogo et al,14 found lower frequencies of 12.5%, 14% and 15%, respectively.

According to the DHS-V in Benin,2 5% of children suffered from wasting. The high frequency in our study could be explained by the effect of concentration of cases in the hospital environment. In addition, the use of MUAC alone made it possible to diagnose 8.5% of cases. This easy-to-use tool, which is little used in several studies including the DHS, deserves to be promoted because it is a good indicator of survival apart from its contribution to the diagnosis of acute malnutrition.7

Chronic malnutrition (stunting)

Hospitalized children were affected by chronic malnutrition in 25% of cases. Musenge et al15 in Zambia, Thiam et al9 in Senegal, Djomo et al16 in DRC had noted higher frequencies of 31.5%; 32% and 86%, respectively. On the other hand Massen et al5 in Algeria and Ouédraogo et al14 in Burkina Faso, in 2016 reported lower frequencies of 10.2% and 13%, respectively.

This frequency of chronic malnutrition in our study is high and could be explained by the high prevalence of chronic malnutrition in the community according to the DHS-V in Benin which is 32%2 and the effect of concentration of cases in the hospital.

Underweight

Our study shows that 33% of hospitalized children were underweight; results similar to those of Thiam et al9 in Senegal (35.5%). On the other hand, Ouédraogo et al14 in Burkina Faso and Musenge et al15 in Zambia had reported lower frequencies of 7% and 13.8%, respectively. Similarly, Djomo et al16 in the DRC reported a higher frequency (48.8%). According to the DHS-V in Benin,2 17% of children are underweight at the community level.

The high frequency of underweight in our study could be explained by the high prevalence of underweight in the community, the effect of concentration of cases in the hospital and the high frequency of acute and chronic malnutrition cases ; underweight being a composite status of the latter.

Over nutrition

Overweight and obesity accounted for 1.6% and 1.1% of cases, respectively. Mabiala-Babéla et al,17 in Congo and Sbai et al,18 in Morocco had reported higher frequencies of 7.1% and 20%, respectively.

These proportions are low and could be explained by the fact that overweight and obesity occur more often in children over 5 years old, whereas the target population of our study was children under five years old. However, the status of overnutrition must be followed up in our context where the double nutritional burden is gradually being established.

At the end of the study, it appears that one in two children has a poor nutritional status in the pediatric department at the CHUD of Parakou, one in three children has acute malnutrition, one in four children has chronic malnutrition and one in three children was underweight. This result reflects the situation at the community level and suggests that bold actions should be taken to reverse this trend. This situation can largely explain the high child mortality rate in Benin. Prospective studies on child feeding needed to understand the poor nutritional status of the children.

None.

By the authors.

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest..

©2023 Noudamadjo, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.