Journal of

eISSN: 2373-4426

Case Report Volume 6 Issue 3

1Department of Pediatrics, Division of Neonatalogy, Saint George Hospital University Medical Center, University of Balamand, Lebanon

2Department of Pediatric Surgery, Saint George Hospital University Medical Center, University of Balamand, Lebanon

3Department of Pediatrics, Division of hematology, Saint George Hospital University Medical Center, University of Balamand, Lebanon

4Department of Pathology, Saint George University Hospital, University of Balamand, Lebanon

Correspondence: Smart Zeidan, MD, Department of Pediatric Surgery, Saint George University Hospital, Achrafieh, Beirut, Lebanon, Tel 96171575625

Received: February 02, 2017 | Published: February 21, 2017

Citation: Zeidan S, Hamzeh R, Bechara E, Hamod DA, Ghandour F, et al. (2017) Gastric Perforation: Unusual Presentation of Gastric Lymphoma in Pediatric Population. J Pediatr Neonatal Care 6(3): 00243. DOI: 10.15406/jpnc.2017.06.00243

Gastric perforation is a potential fatal condition rarely occurs in children. We report a rare case of gastric perforation in a 3year old boy who was found to have gastric T cell lymphoma. Gastric lymphoma should be considered in the differential diagnosis of gastric perforation in children.

Keywords: gastric perforation, gastrointestinal non- hodgkin’s lymphoma, gastric t-cell lymphoma

Gastric perforation is a rare entity in pediatric population. This case highlights the fact that gastric T-cell lymphoma should be considered in front of gastric perforation in children. A delayed diagnosis could be lethal.

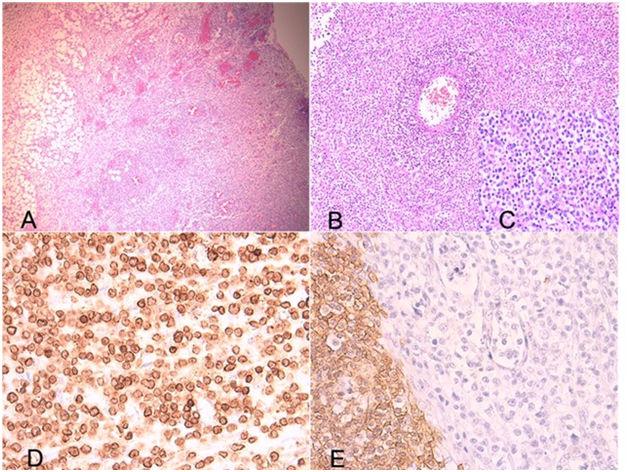

A 3years old boy presented at the hospital with abdominal pain and severe abdominal distension after 5days history of fever treated with Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Abdominal x-ray was done and raised the suspicion of pneumoperitoneum. Abdomen/ pelvis CT showed huge intraperitoneal ascites with pneumoperitoneum, normal liver and spleen with suspected perforation of the stomach (Figure 1: A: Pneumoperitoneum and Ascites. B: Suspected Gastric perforation). Patient underwent urgent laparotomy; gastric perforation was found and repaired. Gastric biopsies were done. Patient kept having fever post-operatively with distended and tender abdomen, abdomen/pelvis CT was repeated to rule out any abscess collection, and showed moderate amount of fluid in the abdomen, mainly anterior to the left colon. Collections showed compartmentalization, a CT- guided drainage done and 100cc of fluid were obtained and culture grew after 48hours in Leuconostoc and streptococcus mitis so Ceftazidime and Metronidazole were switched to Imipenem/Cilestatin. On Day 5 post-op, patient started to have severe abdominal pain with tachypnea and desaturation; abdomen/pelvis CT showed large amount of fluid in the peritoneal cavity, associated with thickening of the parietal peritoneum and re-perforation was suspected. Patient underwent urgent laparotomy where clear fluid was obtained, drain was placed, and biopsies from the liver, omentum and spleen were performed. Immunohistological examination of the gastric biopsies revealed an abnormal T cell lymph proliferation in favor of non-Hodgkin’s T-cell lymphoma (Figure 2: Histopathology of the Gastric Biopsies. A: Low power view from ulcer base showing a diffuse infiltrate involving the full thickness of the gastric wall (H&E x 40). B: Diffuse monotonous infiltrate involving the vessel wall (H&E x 100). C: Medium sized convoluted nuclei with clear cytoplasm and scattered eosinophils (H&E x 400). D: Diffuse membranous positivity of tumor cells with anti-CD3 (IHC x 400). E: Staining with anti-CD20 shows negative tumor cells with positive residual germinal center. Few glandular Lumina with effaced epithelial lining are seen in the middle (IHC x 400). )

Figure 2 Histopathology of the Gastric Biopsies. A: Low power view from ulcer base showing a diffuse infiltrate involving the full thickness of the gastric wall (H&E x 40). B: Diffuse monotonous infiltrate involving the vessel wall (H&E x 100). C: Medium sized convoluted nuclei with clear cytoplasm and scattered eosinophils (H&E x 400). D: Diffuse membranous positivity of tumor cells with anti-CD3 (IHC x 400). E: Staining with anti-CD20 shows negative tumor cells with positive residual germinal center. Few glandular Lumina with effaced epithelial lining are seen in the middle (IHC x 400).

Patient received one cycle of chemotherapy (COP: Cyclophosphamide, vincristine prednisone) however patient was clinically and hemodynamically unstable and he was declared dead at day 12 of admission.

Primary gastrointestinal (GI) tumors are rare entity in infancy and childhood and accounts for less than 5% of tumors in pediatric age group.1 Gastrointestinal lymphomas represent 1.0–1.2 % of all pediatric malignancies, and compose 74-82% of GI-related malignancy.2 Primary non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the GI tract is the most common extra nodal lymphoma in pediatric age group; however, most of them are of B-cell origin. T-cell lymphomas of the gastrointestinal tract are rare and most of the reported cases originated in the small intestine.1,3 The majority of gastrointestinal tumors are non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, however studies on gastric lymphomas in childhood are limited to isolated case reports and most of these cases are Burkitt lymphoma and are associated with Helicobacter pylori infection.4 Gastric perforation is a rare entity in childhood. Peptic ulcer perforation, chronic steroid administration, NSAIDs, severe underlying illness, trauma, iatrogenic perforations are all reported as a differential diagnosis of gastric perforation.5 Perforation is a serious life-threatening complication of gastrointestinal lymphoma, for which high index of suspicion and early diagnosis is essential to avoid death.

The presentation of gastric lymphoma is often unspecific and more suggestive of gastritis or an ulcerous condition rather than a neoplasm; this is why its diagnosis is often delayed. Gastro-intestinal hemorrhage (hematemesis or melena) occurs at the outset in 20–30% of patients, while gastric occlusion and perforation are quite uncommon.6

To our knowledge, this is the first reported gastric perforation due to T-cell gastric lymphoma in pediatric population. A broad literature review of English-language relevant articles published in the last twenty years about pediatric gastric lymphoma revealed no reported Gastric T cell lymphoma and no reported gastric perforation due to lymphoma in pediatric population (Table 1).

|

|

Gastrointestinal tumors Number of cases |

Gastric tumors (%) |

Histopathology of Gastric Tumors |

Presentation: Gastric perforation (%) |

||||||

|

Curtis JL, et al.,4 |

21 |

21(100%) |

Gastric lymphoma 4(19%): Burkitts 3 |

0 |

||||||

|

MALToma 1 |

||||||||||

|

Zhuge Y, et al.,8 |

105 |

64(61%) |

Carcinoma 43 (41%) |

Not assigned |

||||||

|

Sarcoma 46 (43.8%) |

||||||||||

|

Neuroendocrine tumors 11 (10.5%) |

||||||||||

|

Others 5(4.7%) |

||||||||||

|

Kassira N, et al.,9 |

265 |

25(9.4%) |

Burkitt (53%) |

0 |

||||||

|

Other Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma (43%) |

||||||||||

|

Mature T cell Lymphoma 1* |

||||||||||

|

Morsi A, et al.,10 |

54 |

4 (9.2%) |

Burkitts lymphoma 55.8% |

0 |

||||||

|

Others(small cell non cleaved lymphoma, large B cell lymphoma, and mixed type) |

||||||||||

|

Ladd AP, et al.,11 |

58 |

1(1.7%) |

Gastric leiomyosarcoma |

0 |

||||||

|

Bethel C, et al.,12 |

55 |

3(5.4%) |

Gastric sarcoma 2 66.6% |

0 |

||||||

|

Non-Hodgkin’s Burkitts lymphoma 1 33.3% |

||||||||||

|

Zheng N, et al.,13 |

15 |

15(100%) |

Immature teratoma 1 |

0 |

||||||

|

Vascular tumor 1 |

||||||||||

|

Gastric adenomas 2 |

||||||||||

|

Adenocarcinoma 1 |

||||||||||

|

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor 5 |

||||||||||

|

Epitheliomesenchymal biphasic tumor1 |

||||||||||

|

Mixed germ cell tumor 1 |

||||||||||

|

Leiomyosarcoma 2 |

||||||||||

|

Stromal tumors (epithelioid cell type) 1 |

||||||||||

|

Khurshed A, et al.,14 |

60 |

3(5%) |

Signet Ring Cell Carcinoma 2 (66.7) |

0 |

||||||

|

|

|

|

Adenocarcinoma, NOS 1 (33.3) |

|||||||

Table 1 Literature review: Pediatric Gastrointestinal Tumors

*One case of mature T cell lymphoma that was not assigned if in the stomach or other site of the GI tract.

To date there is no ideal treatment approach in gastrointestinal lymphoma. A conservative approach consists of limited resection of obstructed or perforated segment, and biopsies to confirm the diagnosis.2 However recent studies suggest that organ-preservation strategy using chemotherapy alone can be successfully employed in a significant number of patients with primary GI non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.7

Although gastric perforation is a rare entity in childhood, surgeon should consider gastric lymphoma in the differential diagnosis of gastric perforation and should take multiple biopsies in any suspicious case.

None.

Author declares there are no conflicts of interest.

None.

©2017 Zeidan, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.