Journal of

eISSN: 2373-4426

Research Article Volume 10 Issue 2

1Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Mount Kenya University, Kenya

2Department of Biochemistry & Biotechnology Pwani University, P.o. Box 195-80108 Kilifi, Kenya

3Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Mount Kenya University, Kenya

Correspondence: Richard Kipkemoi Lang’at, Mount Kenya University, School of Public Health, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics. Thika (main) campus, General Kago Rd P.O. box 342-01000 Thika, Kenya

Received: December 10, 2019 | Published: April 30, 2020

Citation: Langat R. Determinants of low immunization coverage among children aged 12-23 months in narok south narok county kenya. J Pediatr Neonatal Care. 2020;10(2):52-66. DOI: 10.15406/jpnc.2020.10.00413

Childhood immunization remains one the primary health care core component and the most effective public health interventions for controlling and eliminating life-threatening vaccine preventable diseases in the world. According to 2014 Kenya National Demographic and Health Survey (KDHS), a few children of ages 12 to 23 months in Kenya presented below average in terms of vaccination coverage of children who are fully immunized. Delayed vaccinations would increase the risk for vaccine preventable diseases in the community, therefore the information obtained from this study is to help policy makers come up with sound strategies to increase immunization coverage from 57%- 90% as recommended by World Health Organization. The broad objective of the study was to determine reasons influencing low vaccination coverage between children of ages 12 to 23 months in Narok South sub-county, Narok County in Kenya. This is to contribute to the reduction of morbidity and mortality caused by infectious diseases of public health importance related to vaccine preventable disease.

Methods: This was a cross-sectional descriptive study. The study used mixed methods, both quantitative and qualitative. A structured questionnaire was used to collect data on social demographic and social cultural factors, maternal health care utilization and knowledge. Key informative Interviews and Focus Group Discussions were used to collect qualitative data on 454 mothers/caretakers with children aged between 12-23 months reached in Narok South sub county.

Results: The total number of mothers/caregivers who were interviewed were 454, with a response of 100%. Results of immunization coverage; BCG 73%, OPV1 59%, OPV2 51%, OPV3 49%, Penta1 58%, Penta2 51%, Penta3 50%, Measles 54% and Fully Immunized Children 47%. Further, 47% of the children in the sub-county were fully immunized and 53% were unimmunized. The SD mean for mothers/caregivers and children 31.4 and 17.0 respectively and over 70% of the mothers/caregivers had no formal education. There were significant association predictors with immunization coverage included maternal education (X2 =11.75, df=4 p value=0.02), distance to health facility (X2 =62.30, df=2 p value=0.00), also, there was strong significant association with childbirth ranking (OR=1.218, p value=0.04). Bivariate analysis, there was an association with mothers/caregivers’ who had more than one visits with fully immunized children (χ2=13.54, df =2 and p value =0.001), source of the immunization information OR=0.75 and p value=0.02 and, ultimately, there was association between mother’s/caregiver place of delivery with non-fully immunized children (X2=74.40,df=1 p value=0.01). Predictors of non-fully immunized children in the study population were; place of delivery, family size, education level, source of income, none attendance of Antenatal clinics, distance to the health facility, source of the vaccination information was associated with incomplete fully immunized children.

Conclusion: The immunization coverage for the fully immunized child in the sub county was very low 47%, compared to national 77%. Key players in the immunization sector should identify children who are at risk, deploy reach every child strategy, encourage pregnant mothers to attend ANC, expand outreach services, increase funds allocation to health sector and build more health facilities to improve immunization coverage.

ANC, ante natal care; BCG, Bacillus Calmette Guerin; CHEW, community health extension workers; CHMT, county health management team; CHV, community health volunteers; CI, confidence interval; DHIS2, district health information system; DTP3, diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis; DVI, division of vaccines immunization; EPI, expanded programme on immunization; FGD, focus group discussion; FIC, fully children immunized; GIVS, global immunization vision and strategy; HBR, home-based records; HCW, health care workers; IM, intramuscular; IQR, interquartile range; KDHS, kenya national demographic and health survey; KII, Key informant interview; MCH, maternal child health; MCV, measles vaccine coverage; MDG, millennium development goals; MKU, mount kenya university; MoH, ministry of health; NACOSTI , national council of science & technology; OPV, oral polio vaccine; PCV10, pneumococcal conjugate vaccine; PNC, post-natal care; SCHMT, sub county health management team; SD, standard deviation; SDG, sustainable development goals; SI, sampling interval; TT, tetanus toxoid; UNICEF, united nations children’s fund; VPD, vaccine-preventable disease; WHO, world health organization

According to World Health Organization,1 vaccination is the utmost effective way of averting and controlling life threating childhood illness, disability and death, of which it’s the most cost-effective way. The 4th Millennium Development Goal (MDG) lay emphasis on the importance of children health and mortality. In 2014, World Health Organization (WHO) broadcasted that, vaccination can avert two to three million deaths every year, so it’s crucial to use the vaccine regularly. Furthermore, immunization have led to eradication of smallpox in the world. WHO (2014).1 Furthermore, by forecasting the impact of immunization on mortality, it’s estimated that more than 23 million vaccine preventable diseases deaths would be averted, if vaccination is administered between 2011 and 2020 GAVI (2014). Progress has been made since 2014, but the number of missed opportunities is estimated to be 18.7 million infants not reached with routine immunization services such as penta3, OPV3 and measles vaccines (WHO, 2014).2,3

The fully immunized child is the infant who has been given one dosage of BCG, three dosages of oral polio vaccine (OPV), three dosages of Diphtheria-Tetanus-Pertussis (DPT) and one dosage of measles as per the Division of Vaccine & Immunization Kenya immunization schedule. The number of infants estimated to be vaccinated with diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis (DTP3) containing vaccine are 112 million (84%) (WHO 2013).4,5

In the same vein, the Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI) was started in 1974 by World Health Organization with the role to avert diseases and mortality which are preventable and related to vaccines in the world. Further, the Division of vaccine and immunization unit in Kenya was started in 1980, with its mandate to vaccination against killers’ preventable diseases and deaths, namely; Tuberculosis, Polio, Diphtheria, Whooping Cough, Tetanus and Measles.

According to the 2014 Kenya National Demographic and Health Survey (KDHS 2014) shown below average in terms of vaccination coverage amongst children of ages between 12 to 23 months in Kenya (KDHS 2014). Therefore, the main aim of this study is to determine factors influencing low immunization coverage among children of ages amongst 12 to 23 months in Narok South Sub-County, Narok County in Kenya.

Study design

This was a cross-sectional study, where both quantitative and qualitative methods was used in collecting data. A structured questionnaire was used to collect data on social demographic and social cultural factors, maternal health care utilization and knowledge. Further, Key informant interviews and focus group discussions were used to collect qualitative data and 454 mothers/caregivers with children aged between 12-23 months were reached in Narok South sub county.

Study area

Narok South is situated in Narok county bordering Narok North to the North, Bomet county to the west, Kajiado to the east and Tanzania to the south. The Narok County lies between latitude 0° 50’ and 1° 50´ south and longitude 35° 28´ east.

Target population

The study population involved households with children between 12 to 23 months during the study period (cohort birth).

Sample size determination

Target population was 372,157 (Narok South) according to projected Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (2016), and the under one-year old were 4.6% (15,200). The sample size was arrived as follows, as per Kenya Demographic and Health Survey (KDHS) 2014, Narok South fully immunized children is 57%.

p= the proportion of the target population estimated to have a characteristic being measured taken as 57% (proportion of completely immunized children as per KDHS 2014)

z= Standard normal deviation which is 1.96 at 95 % level of confidence.

P= prevalence of immunization 57%

q=1 – p =1-0.73 =0.27

d=Desired precision is +/- 0.05

DE =Design effect =1.5

The sample size was determined using the formulae below

n = Z2 x p x (1-p)

1.962 x 0.57x (1-0.57) = 377 plus 20% non-response

0.052 = 454 Sample size =377 children

The researcher added 20% non-response proportion to the already determined sample size to give the total number of 454 children aged 12-23 months involved in the study. As per (WHO 2005)6 modified immunization coverage cluster survey, which recommends that the minimum cluster for surveys is 30 villages. Therefore, the sample size of 415 children was given as; children in each cluster =sample size ÷ number of clusters, 454÷ 30= 15.1, therefore 16 children per cluster of 454 sample size.

Sampling procedure

The researcher deployed a multistage sampling, then simple random sampling followed. First, four out of six wards were selected randomly, namely Mulot, Sogoo, Naroosura/Majomoto and Loita with children aged between 12-23 months. Further, the following sub-locations were selected under various wards, namely; Mulot ward (Mulot, Kuto, Enelerai, Rongena, Ilmotiok, Sagamian, Tendwet Sogoo and Nkaroni) sub-locations. Additionally, under Ololulunga ward the following sub-locations were selected; Nkakori, Lemeck, Olkiriane, Ololulunga, Melelo, Oloshapani and Ereteti. Furthermore, Naroosura/Maji moto ward; Maji Moto, Elengata Enterit and Naroosura sub-locations were selected. Lastly, under Loita ward, the following sub-locations were selected to be included in the study; Entasekera, Olmesutie and Morijo loita. Then transcribe a corresponding number beside the first community listed on the Cluster identification form, that assisted in administering questionnaires in which the cumulative population equals or exceeds the cluster population. Additionally, the sampling interval was important concept in identifying clusters, where it was arrived via the following;

Sampling interval (SI) = entire population to be studied.

So, the sampling interval was determined by dividing the target population that was surveyed (15,200) by the number of clusters (30). Further, the sampling interval was 507 which was used in systematically selecting wards from the sampling frame. The first sub-location was selected at random using computer excel generated random number and it was less or equal to sampling interval, where random sampling interval was (357). Then, identity the first village in which cluster one was located. This was done by identifying the starting village in the list where cumulative population was not expected to exceed or equal to random number.

For the second cluster, sub-location was determined by adding number which identified the location of the previous cluster and sampling interval. Below are how the clusters is going to be computed.

Cluster 1 population =357 (random number)

Cluster 2 population =357 + 507=864 (random number + sampling interval)

Cluster 3 population =864 + 507= 1371 (number for cluster 2 + sampling interval)

Cluster 4 population =1371 + 507= 1878 (number for cluster 3 + sampling interval)

Where the following wards were selected plus their populations that formed sampling frame (appendix 1). Eventually, the same process was repeated until 30 clusters are reached in the populations, as illustrated in appendix 1.

General characteristics of the study population

There were 454 mothers/caregivers who completed interviews for household surveys and immunization questionnaires in five wards of Narok South Sub County. The overall household response rate was 100% across all the wards in the study area. As illustrated in Figure 1 the ages of the mothers/caregivers were normally distributed with a mean age of 31 years and standard deviation of 6.6. In addition, the total number of children sampled during the period of review were 454, with a mean of age 17 months, SD ±3.15, range (12-23 months) and the median age was 17 months (interquartile range [IQR]: (12-23). There was no association between age groups and fully immunized children χ2 =3.6195, df=4, and p value=0.460.

The status of immunization coverage in Narok South subcounty

In respect to immunization status, fully immunized children were 47%, followed by partially immunized number of children with 131 (29%) and the least was unvaccinated children with 110 (24%) as shown in pie chart below (Figure 2). Immunization coverage results as per Narok South sub county (Figure 3) showed BCG coverage was 73% (CI 51%-56%), OPV1 59% (CI 48%-50%), OPV2 51% (CI 41%-44%), OPV3 49% (CI 31%-35%), Penta1 58%, Penta2 51%, Penta3 50%, MCV1 54% PCV1 58%, PCV2 50%, PCV3 50% and FIC 47% as illustrated in the graph below. BCG 73% had the highest coverage while fully immunized children (FIC) were the lowest with 47%, as illustrated in the graph below.

Immunization status coverage by card in the study area

In relation to immunization by card only, BCG coverage was 73%, OPV1 65%, OPV2 64%, OPV3 63%, Penta1 66%, Penta 2 64%, Penta3 63%, PCV1 66%, PCV2 64%, PCV3 63% MCV 60% and FIC 59% as illustrated in the graph below (Figure 4).

Immunization dropout rate status in the study area

High dropout rate was observed across all the immunization strata, as illustrated in Figure 5. The dropout rate of Penta 1 to Penta 3 was (14.33%), OPV1 to OPV 3 (17.5%) and BCG to MCV was 25.8%. The highest dropout rate was observed in BCG to measles vaccine coverage with 25.8%, followed by OPV1 to OPV3 with 17.5%, then Penta1 - Penta3 (14.3%) and the least was penta1 to measles with 13.8%. One of the questions asked to KIIs was “What are some of the reasons that contribute to incomplete vaccination status of children?” One of the KII (Epi nurse SCHMT member) said, “Stock-outs of antigens (i.e BCG, MR and OPV), stock-outs of immunization devices, missed opportunities, lack of defaulter tracking mechanisms at health facility and cold chain breakdown” (Table 1).

Variables |

N=454 |

Fully immunized |

Partially/Un immunized children |

OR |

P value |

||||

Age of mothers/caregivers |

Coverage |

LCL |

UCL |

Coverage |

LCL |

UCL |

|||

15-19 years |

4.69% |

2.27% |

8.46% |

3.32% |

1.44% |

6.44% |

0.959 |

0.75 |

|

20-29 years |

32.86% |

26.60% |

39.61% |

37.34% |

31.22% |

43.78% |

|||

30-39 years |

53.52% |

46.58% |

60.36% |

47.72% |

41.27% |

54.23% |

|||

40-49 years |

8.45% |

5.09% |

13.03% |

10.79% |

7.17% |

15.41% |

|||

Above 50 years |

0.47% |

0.01% |

2.59% |

0.83% |

0.10% |

2.97% |

|||

Education level |

None |

8.45% |

5.09% |

13.03% |

58.09% |

51.59% |

64.39% |

4.737 |

0.00 |

Primary |

7.51% |

4.35% |

11.91% |

27.39% |

21.86% |

33.48% |

|||

Secondary |

72.30% |

65.77% |

78.20% |

7.88% |

4.81% |

12.04% |

|||

College/university |

11.74% |

7.74% |

16.84% |

6.64% |

3.84% |

10.56% |

|||

source of wealth |

Business |

31.46% |

25.28% |

38.15% |

19.09% |

14.33% |

24.63% |

0.693 |

0.00 |

Farming |

28.64% |

22.67% |

35.21% |

39.42% |

33.21% |

45.90% |

|||

formal employment |

14.55% |

10.11% |

20.02% |

5.39% |

2.90% |

9.05% |

|||

Housewife |

4.23% |

1.95% |

7.87% |

7.47% |

4.49% |

11.55% |

|||

Pastoralism |

19.25% |

14.18% |

25.19% |

26.56% |

21.09% |

32.61% |

|||

Student |

1.88% |

0.51% |

4.74% |

2.07% |

0.68% |

4.77% |

|||

Religion |

R. Catholics |

21.60% |

16.27% |

27.73% |

27.39% |

21.86% |

33.48% |

1.042 |

0.67 |

Protestants |

56.34% |

49.39% |

63.10% |

50.62% |

44.13% |

57.10% |

|||

Islam |

7.04% |

3.99% |

11.35% |

4.98% |

2.60% |

8.54% |

|||

None |

15.02% |

10.51% |

20.54% |

17.01% |

12.49% |

22.36% |

|||

Marital status |

Divorce |

1.41% |

0.29% |

4.06% |

2.07% |

0.68% |

4.77% |

1.034 |

0.77 |

Married monogamous |

83.57% |

77.90% |

88.28% |

83.82% |

78.55% |

88.23% |

|||

Separated |

0.94% |

0.11% |

3.35% |

4.15% |

2.01% |

7.50% |

|||

Single |

6.57% |

3.64% |

10.78% |

5.81% |

3.21% |

9.55% |

|||

Widow |

7.51% |

4.35% |

11.91% |

4.15% |

2.01% |

7.50% |

|||

Table 1 Socio-demographic characteristics of the mothers/caregivers in relation to immunization completion in the study area

Socio-demographic of the respondents (mothers/caregivers)

A total of 432 (95%) mothers and 22 (5%) fathers of children aged 12-23 months were interviewed during the study period. The mean age for mothers/caregivers was 31.4 years. Mothers/caregivers aged between 30 to 39 years had the highest immunization coverage, 229 (53.5%). In respect to marital status, majority of respondents were married and their children fully immunized status was at 84% with the least was those mothers/caregiver’s who had already separated with less than 1% (FIC). Further, there was no association between marital status and the proportion of fully immunized children (OR=1.034002, p value= 0.7712). There was no association of mothers/caregivers age groups with proportion of fully immunized (OR= 0.959, p value=0.7467). In regards to religion, there was no association between religion and fully immunized children (OR=1.042457, p value =0.667). On the other hand, maternal education and socio-economic status had significant associations between them with the proportion of fully immunized children (OR=4.74, p value =0.02 and OR =0.69, p value =0.001 respectively).

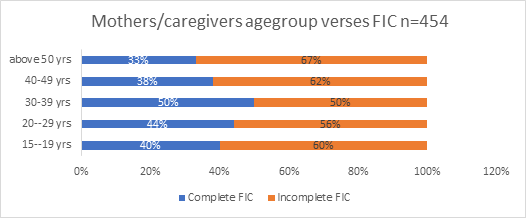

Relationship of mothers/caregivers’ education and immunization status in the study population

Regarding the mothers/caregiver’s education level (Figures 6&7), majority of the caregivers (215, 47%) had not gone to school, followed by primary educated ones at 107 (24%) and the least in proportion were the university educated (62, 14%). Of which, fully immunized children for mothers/caregivers with no education was low as compared to the educated ones. There was significant association between education level, where mothers/caregivers with nil or primary-only education are strongly associated with non-fully immunized children (χ2=11.7483, df=4 and p value=0.002). Majority of the respondents in the households were largely female (95%). As displayed in Figure 8 mothers. Caregivers whose age groups were between 30-39 years had the highest proportion of fully immunized children (229, 50%), followed by mothers/caregivers of age range 20-29 years (160, 44%). In respect to age group, there was no association between maternal age groups with proportion of fully immunized children (χ2=0.959, df=4 and p value=0.75) (Figures 9&10).

Figure 8 Age group of mothers/caregivers with children aged 12-23 months against fully immunized children.

Figure 10 Relationship of mothers/caregiver’s source of wealth and immunization status in the study population.

Association of religion of mothers/caregivers of children aged 12-23 months against full immunization

In terms of religion, majority (242, 53%) of the mothers/caregivers were protestants, then Catholics with 112 (25%) and the least was Islam religion with 32(7%). There was no association between religion and fully immunized children (χ2=1.042, df= 3 and p value= 0.67. As illustrated in Figure 11, majority 34.4% were farmers, followed by business (24.9%), then nomadic pastoralists with 23.1% and the least was students with 2%. There was significant association between source of wealth and fully immunized child (χ2 =25.19, df=5 and p value= 0.00). Related to marital status, more than three-quarters of the mothers/caregivers ,370 (81%) were married, followed by single 34 and divorce been the least as per the respondents, as demonstrated in Figure 12. There was no significant association between marital status and fully immunized child (χ2 =1.034, df=5 and p value= 0.77) (Table 2).

Variables |

N=454 |

Fully immunized |

Partially/Un immunized children |

OR |

P value |

||||

Coverage |

LCL |

UCL |

Coverage |

LCL |

UCL |

||||

Sex of children |

Females |

51.17% |

44.25% |

58.06% |

53.53% |

47.01% |

59.95% |

0.912 |

0.616 |

Males |

48.83% |

41.94% |

55.75% |

46.47% |

40.05% |

52.99% |

|||

Birth ranking |

1st |

10.85% |

7.00% |

15.83% |

12.08% |

8.24% |

16.89% |

1.218 |

0.0411 |

2rd |

27.83% |

21.91% |

34.38% |

33.33% |

27.40% |

39.68% |

|||

3rd |

28.77% |

22.78% |

35.37% |

32.92% |

27.01% |

39.25% |

|||

4th |

32.55% |

26.29% |

39.30% |

21.67% |

16.63% |

27.42% |

|||

Size of the family |

1 |

17.84% |

12.95% |

23.65% |

16.60% |

12.13% |

21.91% |

0.984 |

0.8994 |

2 |

43.19% |

36.44% |

50.14% |

42.32% |

36.01% |

48.83% |

|||

3 |

35.68% |

29.25% |

42.51% |

40.25% |

34.00% |

46.74% |

|||

4 |

3.29% |

1.33% |

6.65% |

0.83% |

0.10% |

2.97% |

|||

Age group in months |

12-17 months |

61.03% |

54.13% |

67.62% |

53.94% |

47.43% |

60.36% |

0.748 |

0.127 |

18-24 months |

38.97% |

32.38% |

45.87% |

46.06% |

39.64% |

52.57% |

|||

Table 2 Association of completion of immunization with socio-demographic characteristics of the children in the study area

Socio-demographic characteristics of the index child

The total number of eligible children who sampled during the study period were 454, of which 232 (51%) were female, 49% (222) are from rural area. Majority of children (61%) were aged between 12-27 months and the rest were 18-24 months. Further, there was no association between sex of the child and fully immunized (χ2=0.2511, df=1 and p value=0.616). As shown in Figure 9, regarding birth ranking of the children in the households, majority 400 (88%) were ranked two and above and least 52 (12%). There was a significant association with child birth ranking with fully immunized children χ2=1.218, df=3 and p value =0.0411.

Maternal health care utilization

Table 3 Majority of respondent (mothers), 319 (71%) delivered their children at home while 135 (29%) at health facility. Majority of the respondents in the households were largely female 95% and 5 % males. Other the other hand, 176 (71%) of caregivers had visited ante-natal clinic visits at least once, 54 (20%) had visited more than two times and 24 (9%) had visited more than three times in the health facilities around the sub county. As shown in figure 15, slightly more than three quarters, 298 (76%), mothers had attended ANC services at least once, followed by none 129(28%) and the least was mothers who had at attended mother than three times with 25 (6%). Bivariate analysis, there was an association with mothers/caregivers’ who had more than one visits with fully immunized children (χ2 =13.54, df =2 and p value =0.001). As shown in Figure 13, under the ante natal care (ANC), most mothers 233 (51%) attended one-time ANC visit, followed by none with 129 (28%) and the least was 25 (%). This implies that mothers/caregivers utilized the ante natal services in health facilities in the study area. There was no relationship between fully immunized with mother/caregivers attending ANC (χ2=13.3939, df=1 and p value=0.2938) (Figure 14).

Variables |

Categories |

Fully immunized |

Partially/Un immunized children |

OR |

p value |

||||

Coverage |

LCL |

UCL |

Coverage |

LCL |

UCL |

||||

ANC visits |

No |

21.6% |

15.8% |

28.4% |

26.2% |

20.4% |

32.5% |

1.286 |

0.292 |

Yes |

78.4% |

71.6% |

84.2% |

73.9% |

67.5% |

79.6% |

|||

Parity |

One Child |

13.6% |

9.3% |

19.0% |

13.3% |

9.3% |

18.2% |

1.050 |

0.801 |

Two children |

53.1% |

46.1% |

59.9% |

45.2% |

38.8% |

51.8% |

|||

Three children |

28.2% |

22.2% |

34.7% |

39.4% |

33.2% |

45.9% |

|||

Four children |

5.2% |

2.6% |

9.1% |

2.1% |

0.7% |

4.8% |

|||

place of delivery |

Health facility |

56.8% |

49.9% |

63.6% |

17.8% |

13.2% |

23.3% |

0.165 |

0.000 |

Home |

43.2% |

36.4% |

50.1% |

82.2% |

76.7% |

86.8% |

|||

PNC visit |

No |

53.3% |

46.3% |

60.2% |

72.3% |

66.1% |

77.9% |

2.283 |

0.000 |

Yes |

46.7% |

39.8% |

53.7% |

72.3% |

22.1% |

33.9% |

|||

ANC visits |

1-time |

66.3% |

58.4% |

73.5% |

77.1% |

70.0% |

83.3% |

1.794 |

0.002 |

2-times |

20.6% |

14.6% |

27.7% |

20.5% |

14.6% |

27.4% |

|||

more than 3 times |

13.1% |

8.3% |

19.4% |

2.4% |

0.7% |

6.1% |

|||

Contraceptive use |

Yes |

57.6% |

50.6% |

64.3% |

58.7% |

52.1% |

65.1% |

1.050 |

0.801 |

No |

42.5% |

35.7% |

49.4% |

41.3% |

34.9% |

47.9% |

|||

Table 3 Percentages of mothers/caregivers who utilize maternal health services against FIC

Association of mothers' place of children delivery against fully immunized children

More than three-quarters of mothers, 71% (319) most mothers delivered at home while 29% (135) delivery at health facility as portrayed in the graphical presentation below (Figure 15). In relation to infant immunization coverage, Mothers who delivered at health facility had 74% fully immunized children compared to those who delivered at home with 68%. From bivariate analysis, there was an association between place of delivery of infants with non-fully immunized children (χ2=74.40, df =1 and p value 0.001).

Mothers/caregiver’s contraceptive use with immunization status in the study area

Slightly more than half, 57% (257) of mothers/caregivers were using contraceptive for family planning, while 43% (197) were not using contraceptive in the study area. From bivariate analysis, the results implied that there was no association between contraceptive use and non-fully immunized children in the study area, p value=0.801 (χ2 = 0.0634, df=1 and p value=0.801) (Figure 16).

Reasons for incomplete vaccination

On the other hand, slightly half 50% of the mothers/caregivers indicated unmindful of essentials for vaccination, followed by not important return for immunization dosage and not knowing place/time of vaccination with 22%, whilst the least is wrong ideas about contraindications with 2% (Figure 17). Slightly more than half, 173 (53%) of mothers/caregivers had no faith in immunization, followed by those who suspended immunization until another time (busy) with 100 (30%), then cultural/religions beliefs 30 (9%) and the least was rumors with 25 (8%) (Figure 18) (Table 4). Slightly more than half of the respondents, 235 (52%) have heard about immunization while 215 (48%) had not. Further, on source of immunizations to respondents, majority 183(51%) have heard about immunization through community health workers, followed by health workers at the health facility 68 (19%) and the least was through newspapers 5(1%). Regarding to knowledge on vaccine preventable diseases, majority of respondents, 278 (61%) have heard of measles, and polio 161(36%). Under knowledge on the number of times a child is supposed to be immunized, half of the respondents did not know 229 (51%), followed by one time 91(21%) and the least was three times 29 (6%). In regards to whether vaccination may cause harm to your child, majority, 45% cited yes while 11% said no and the rest, 39% did not know. As per the FGD, most of them were in agreement that, creating time for vaccination was problematic and also, been busy with household errands. Other the other hand, the key informants mentioned that, at times health facilities would be out of vaccines, have inadequate staffing and the striking of health care providers. One of the KII, said a few of the health facilities in the sub county had one staff per health facility and if the same staff goes for leave, the facility would remain closed, hence no immunization services (Figure 19).

Variables |

Categories |

Fully immunized |

Partially/Unimmunized children |

OR |

P value |

||||

Coverage |

LCL |

UCL |

Coverage |

LCL |

UCL |

||||

Age for vaccination start |

Just after birth |

42.7% |

35.9% |

49.6% |

33.1% |

27.0% |

39.5% |

0.90 |

0.13 |

Four weeks after a birth |

19.0% |

13.9% |

24.9% |

21.9% |

16.8% |

27.8% |

|||

Six weeks after a birth |

5.7% |

3.0% |

9.7% |

10.3% |

6.7% |

14.9% |

|||

No idea |

32.7% |

26.4% |

39.5% |

34.8% |

28.7% |

41.3% |

|||

ever visited health facility for any service |

No |

45.2% |

38.3% |

52.2% |

64.3% |

57.8% |

70.4% |

2.18 |

0.00 |

Yes |

54.8% |

47.8% |

61.7% |

35.7% |

29.6% |

42.2% |

|||

source of the information for vaccination |

Immunization card |

70.0% |

63.3% |

76.0% |

51.5% |

45.0% |

57.9% |

0.72 |

0.00 |

Recall |

12.2% |

8.1% |

17.4% |

17.0% |

12.5% |

22.4% |

|||

Immunization card + recall |

5.2% |

2.6% |

9.1% |

5.8% |

3.2% |

9.6% |

|||

None |

12.7% |

8.5% |

17.9% |

25.7% |

20.3% |

31.7% |

|||

Number of vaccination times |

One time |

19.1% |

14.0% |

25.0% |

21.5% |

16.5% |

27.3% |

0.97 |

0.58 |

Two times |

8.6% |

5.2% |

13.2% |

5.5% |

3.0% |

9.2% |

|||

Three times |

6.7% |

3.7% |

10.9% |

6.3% |

3.6% |

10.2% |

|||

Four times |

18.1% |

13.1% |

24.0% |

12.2% |

8.4% |

17.1% |

|||

no response |

14.8% |

10.3% |

20.3% |

17.3% |

12.7% |

22.7% |

|||

Don’t know |

32.9% |

26.6% |

39.7% |

37.1% |

31.0% |

43.6% |

|||

child start for vaccination |

just after birth |

38.7% |

32.1% |

45.6% |

|

23.0% |

34.9% |

0.88 |

0.08 |

four weeks after a birth |

23.1% |

17.6% |

29.4% |

28.7% |

20.7% |

32.2% |

|||

Six weeks after a birth |

25.5% |

19.8% |

31.9% |

26.2% |

24.2% |

36.2% |

|||

No idea |

12.7% |

8.6% |

18.0% |

30.0% |

10.9% |

20.4% |

|||

Awareness of vaccine preventable diseases |

Measles |

59.4% |

52.5% |

66.1% |

|

57.7% |

70.2% |

1.03 |

0.74 |

Diphtheria |

0.9% |

0.1% |

3.4% |

64.1% |

0.1% |

3.0% |

|||

Polio |

38.7% |

32.1% |

45.6% |

0.8% |

27.4% |

39.7% |

|||

Tetanus |

0.9% |

0.1% |

3.4% |

33.3% |

0.1% |

3.0% |

|||

Where did you hear about vaccination |

Community health volunteers |

50.9% |

43.2% |

58.5% |

51.9% |

44.4% |

59.3% |

0.94 |

0.43 |

Health workers at health facility |

20.8% |

15.0% |

27.6% |

17.5% |

12.3% |

23.8% |

|||

Community health extension workers |

7.5% |

4.1% |

12.5% |

6.6% |

3.4% |

11.2% |

|||

Radio |

18.5% |

13.0% |

25.1% |

18.6% |

13.2% |

25.0% |

|||

TV |

1.2% |

0.1% |

4.1% |

2.7% |

0.9% |

6.3% |

|||

Newspaper |

1.2% |

0.1% |

4.1% |

1.6% |

0.3% |

4.7% |

|||

Vaccination may cause harm to your child |

Yes |

45.5% |

38.7% |

52.5% |

36.5% |

30.4% |

42.9% |

0.92 |

0.12 |

No |

11.3% |

7.4% |

16.3% |

13.3% |

9.3% |

18.2% |

|||

Don’t know |

39.0% |

32.4% |

45.9% |

43.2% |

36.8% |

49.7% |

|||

Table 4 Association fully immunized children and Mother/caregivers’ knowledge on immunization

Figure 19 Association of Mothers/caregivers’ proximity to a health post and proportion of fully immunized children.

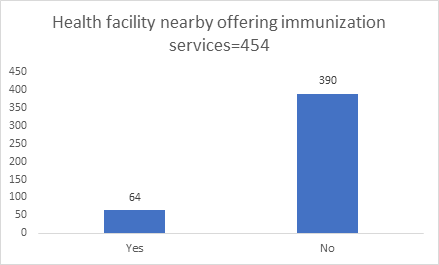

As shown in Figure 20, more than three quarters of the caregivers from the study population 390 (86%) have no health facilities or vaccinations post near them. While, 64 (15%) had health facilities or vaccination post close to them. Regarding to KII (health care providers) and FGDs (mothers/caregivers/opinion leaders), all of them concurred that, communities do complain of distance in accessing the health facilities and terrain with scarce transport. In regard to distance to health facility, majority of caregivers 200 (44%) had to cover over 11 kilometers to access immunization services within the sub-county, 174 (38%) mothers/caregivers had to travel between (6-10 kilometers) and 80 (18%) covered less than five kilometers to reach vaccination post. As per the Pearson chi test, there was significant association between distance to the health facility and fully immunized children χ2=62.30, df=2 and p value=0.00 (Figure 21).

Most mothers/caregivers 300 (68%) would prefer to use boda boda (motorcycle taxi) as means of transport to take their children to vaccination health facility, followed by walking by foot with 107 (24%) and the least would choose 37(8%) to use matatus. As illustrated in figure 24 ,the graph demonstrates mode of transport by mothers/caregivers to the health posts. As per the Pearson chi test, there was an association between distance to the health facility and fully immunized children χ2= 26.55, df=2 and p value=0.00 (Figure 22).

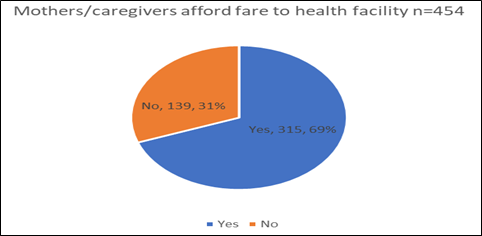

Figure 22 Relationship between mothers/caregivers with affordable fare to access health facility with immunization status.

As shown in Figure 23 mothers/caregiver’s transport fare to the health facility, majority, 315 (69%) mothers/caregivers cannot raise transport fare to take their children for immunization services in the study area, while 139 (31%) of the respondents could afford transport fare to the vaccination health facility for the immunization services. There was significant association between fully immunized child and affording transport to the health facility (χ2= 6.1341, df=1 and p value=0.013).

Majority of mothers/caregivers as per the graph above (figure 26), 245 (54%) indicated that, it takes between 21 to 30 minutes to be served in a given health facility, followed by less than 20 minutes 174(38%) and the least 35 (8%) was over 45 minutes to be served in the facility. In regards of number of vaccinations that the child should receive, majority of mothers/caregivers did not know the number of times a child can be immunized, followed by one-time vaccination and the least was three times. The Pearson chi test (χ2= 14.8209. df=2 and p value=0.01), implied that, there was association between time to be served by health care worker with fully immunized children (Table 5). As publicized in Table 5 above, the multivariate logistic regression analysis was done to test the association between fully immunized children and predictors for non-immunization. As a result, the following factors were associated to low immunization coverage in Narok South sub county were as follows; education level (p value=0.02, O.R=1.38) , place of delivery (p value=0.00, O.R=0.26), size of the family (p value=0.86, O.R=1.04), source of income (p value=0.01, O.R=0.69) , Source of the immunization information (p value=0.02, O.R=0.75), distance to the health facility (p value=0.02, O.R=1.38) . Children who are born at the health facility are four times likely to be fully immunized as compared to those born at home. Further, mothers who attended at least one ANC visit are three times likely to be fully immunized. Further, mothers/caregiver’s education status, ANC visits, poor knowledge on immunization, size of the family, distance to the facility and place of delivery were forecasters of fully immunized children in the study area.

Predictor indicators |

Odds Ratio |

95% |

C.I. |

P-Value |

Education level |

1.3826 |

1.0480 |

1.8240 |

0.0219 |

Place of delivery |

0.2568 |

0.1165 |

0.5657 |

0.0007 |

Size of the family |

1.0360 |

0.6940 |

1.5465 |

0.8627 |

Source of income |

0.6903 |

0.5186 |

0.9188 |

0.0111 |

Source of the information immunization |

0.7453 |

0.5865 |

0.9472 |

0.0162 |

Distance to the facility |

0.1919 |

0.1062 |

0.3468 |

0.0000 |

No of children in the household |

0.8887 |

0.6056 |

1.3040 |

0.5463 |

Ever had about vaccination |

1.3054 |

0.7329 |

2.3250 |

0.3655 |

Table 5 Multivariate logistic regression of predictors of non-immunization in the study area

Immunization coverage in narok south sub county

The aim of the study was to understand the Determinants of low immunization coverage status among children aged 12-23 months in Narok South Sub County. Further, this chapter presents results, conclusions and key recommendations to the key stakeholders. The study findings indicated that the Penta 1 coverage was 58%, penta3 55%, measles 55 % and fully immunized child was 47% while the unimmunized children coverage was 53% in the sub county. The fully immunized coverage (FIC) for the sub county was 47% which is very low compared to the national immunization coverage target which is 80%, further the World Health Organization (WHO) recommendation target is 90%. For children to achieve maximum protection, there was need for children to be given timely vaccines to prevent them from getting vaccine preventable diseases.7–34

Socio-demographic factors of mothers/caregivers in the study area

A total of 432 (95%) mothers and 22 (5%) fathers of children aged 12-23 months were interviewed during the study period. The overall household response rate was high across all the wards was 100%. As per this study mother/caregivers with wealth tend to be [AOR = 1.1467 (95% CI: 0.9497, 1.3845)] times likely to be fully immunized compared to poor mothers/caregivers who had low immunization coverage in respect to fully immunized children. Similarly, this is a congruent with a study carried out by Kiptoo that revealed that mothers/caregivers who earned less than Kshs. 5000 (USD 50) were three times not likely to have their children fully immunized. Other congruent studies conducted by Dikiema et al.,11 and Wado et al,.33 also corresponds with this study, where there was predictor between wealth and fully immunized children (FIC). Furthermore, distance to the health facility was a forecaster to full immunization coverage in the study area. Of the mothers/caregivers, 73% could not afford transport fare to take children to immunization health post, hence affecting the fully immunized coverage in the study area. In respect to this study, there was significant association between fully immunization children with mothers/caregivers who did not have fare to access transport to the health facility (χ2= 6.1341, df=1 and p value=0.013). In addition, another predictor which contributed to low coverage of fully immunized children in the study area was nomadic lifestyle, where nomadic pastoralist moves from one place to another in search of pasture to their cattle. Other study conducted by Kiptooo, correspond with the findings of this study, where one of the predictors of low immunization coverage was nomadic lifestyle. Majority of the respondents in the study area were farmers, followed by nomadic pastoralists, their major livelihood being cattle rearing, where they travel from one place to another looking for pastures. A similar study carried out by Kiptoo, concurred with the same findings of low immunization coverage to be 23%. In addition, other studies with similar studies were carried out by Ethiopia by Sisay et al.,19 with lower fully immunized child results of 38.3%, and Mohamud et al.,25 had also lower results of 36.3% concurred with the findings. Furthermore, other studies that were in congruence were an Ethiopian study which showed low fully immunized children coverage of 66% Lakew et al.,21 and 55% by Nozaki.

In regard to the dropout rates, the proportion of children with evidence of valid dose vaccination varied across geographical zones, mothers/caregiver’s education and age and wealth index quintile. There were high dropout rates between penta1 to penta3 and BCG to measles 14.3% and 25.8% respectively. Similarly, a study carried out by Baguune et al.,8 showed high dropout rates of BCG to measles of 31.5%. Girmaye et al.,23 concurred with the same findings, where penta1 to Measles dropout was at 16%. Basically, high dropout rates between penta1 and measles suggested that most mothers/caregivers are not utilizing the health facilities within the sub county on immunization services. According to this study, penta1 to penta3 dropout rate was high with 14.3%, which was concurrent with the results of a study carried out by Girmaye et al.,23 with a high dropout rate of 25.6%. Further, a survey conducted by JSI et al.,17 in Werega, Ethiopia showed that, there was drop out of penta1-penta3 of 15%. Generally, the children with higher crude coverage and card availability have higher proportion of children with evidence of valid dose and vice versa.

In the same breath, Penta1 to Penta3 dropout rates was high, which could be due to the fact that mothers/caregivers are having challenges in accessing the health facilities for second or third doses of vaccine.

Slightly over fifty percent of the mothers/caregivers showed being unmindful of essentials for vaccination, this means that majority of mothers don’t mind returning their children for second or third vaccine doses. Most respondents during focus group discussion said that they only know of BCG and measles vaccines. In fact, on the of the mothers said “mtoto akishapewa chanjo ya mkono na miguu, tunajua chanjo imekwisha”. (If a child has been given BCG and measles vaccines, then the child has completed immunization). Other respondents said they feared side effects and they had no faith in immunizations. Regarding to KII, most of the respondents seemed to concur with mothers who said that, they only know of BCG and measles vaccine. Furthermore, majority 42% of caregivers/mothers mentioned that health facilities for offering immunization services was too far. Majority of respondents who reside close to health facility were 15 times likely to have their children fully immunized compared to those who travelled or walk more than one hour to the nearest immunization facility. So, distance to the health facilities was associated with incomplete vaccination of children (χ2=62.30, df=2 and p value=0.00). This finding was consistent with other studies conducted by Kiptoo, Dikiema et al.,11 and Wado et al,.33 pertaining to distance to near health facilities offering immunization services. Further, most the respondents a long Loita are Naroosura /Maji Moto are nomadic pastoralist, thus the immunization coverage was low because most of the mothers/caregivers had relocated for grazing. This was also supported by both key informant interviews (KII) and focus group discussants (FGDs) who agreed that, during dry seasons most residents relocate to look for greener pastures in the neighboring county Tanzania, hence children missed out on second and third doses of vaccine.

One of the focus group discussion respondents said, “Sisi wakati wa kiangazi tunaenda tutafutia ngo’mbe nyasi na maji, mambo ya chanjo inasaulika” During dry seasons travel with our animals in search of pastures and ignore children immunization. Overall, the factors which were associated with low immunization coverage in Narok South sub county were as follows; education level (p value=0.02, O.R=1.38) , place of delivery (p value=0.00, O.R=0.26), size of the family (p value=0.86, O.R=1.04), source of income (p value=0.01, O.R=0.69), source of the immunization information (O.R=0.75 and p value=0.02,), distance to the health facility (P value=0.02, O.R=1.38). Respondents with children whose education was a little or nil primary education had a significant association with not fully immunized children (p value=0.02). Similarly, a survey study carried out in Nepal on immunization inequalities displays that children with non-educated parents are associated with not fully immunized.32

In respect to multivariable logistic regression logistic between fully immunized children and maternal education level, ANC visits, size of the family, birth ranking age of the mother/caregivers with age more than 21 years indicated that, there was significant association with a p value < 0.05). This correspond with other studies carried out by Kiptoo and Girmay at al.,23 which showed a relationship between FIC and, mothers/caregiver’s education status, ANC visits, poor knowledge on immunization, size of the family, distance to the facility and place of delivery. One of the KIIs cited the following reasons for low immunization coverage in the sub county. “Shortage of skilled healthcare worker/ inappropriate staff skill gaps on EPI among the existing workforce. Erratic supply of EPI logistics for instance syringes, antigens, sparse distribution of health facilities which affects access of health care services to most women and children in the area. Inadequate funds for facilitation of mobile out-reach services in hard to reach areas. Lack of facilitation to conduct preventive cold chain maintenances of cold chain equipment’s. Poor monitoring and evaluation institutionalization in the sub county and county, in adequate supportive supervision both by the County and Sub-County teams due to inadequacy in funding. Lack of storage sites for immunization logistics at both County and Sub-county levels”.

EPI sub county focal person.

Maternal health care utilization

Under maternal health care utilization services, slightly more than half 71% mothers had at least visited health facility once for Ante Natal Services (ANC); therefore, mothers would utilize the services offered in the health facilities. Moreover, relating to delivery, 30% of the mothers delivered in a health facility while, majority 70% of the mothers delivered at home inferring that mothers do not utilize delivery services in the health facilities. This implied that, most mothers delivered at home than at the hospital, hence they missed services like health education on importance of immunization services to the infants. This concurred with participants of FGDs, where most of them cited that most mothers delivered at home, citing distance to the health facilities, long travelling hours covered by mothers/caregivers to seek immunization services, lack of transport to access the services, lack of money by mothers/caregivers for transport payments and rough terrain. One of the focus group discussants said, “Hospitali ya serikali huwa mbali sana na pia milima na tunaogopa wanyama wa porini” translating to “The government health facility was far, the area was hilly which makes accessibility difficult and in addition there are wild animals on the way to the facility. On the other hand, the KII, also mentioned rough terrain, vaccines stock outs, shortage of health care workers and inadequate funds to support outreach immunization services. For instance, one of the KII stated: “the partner who was funding outreach services has pulled out because of stoppage of funding by the donor”. One of the key informants said “There was only one health facility in Ilmotiok ward to support the community with health service delivery”.

This study revealed that children aged 12-23 months who were born in a health facility were more {AOR = 0.2332 (95% CI: 0.1467, 0.3708} likely to be fully immunized compared to those are born at home. A similar study results by Kiptoo also showed that children who are born at health facility are five times more likely to be fully immunized compared to those born at home. On the other hand, another study carried out in Ethiopia by Mesfin, indicates that children aged 12-23 months born at the health facility are likely [AOR = 2.4 (95% CI: 1.38, 3.65)] to be fully immunized compared to those children who are born at home. A study by Awino, was also coherent with our results indicating that index children born at health facility are more likely to be fully immunized that those born at home. In addition, other studies which share analogous results were conducted by Diekema et.al.,11 with relationship of place of delivery and fully immunized children. Pertaining to contraceptive, majority 57% of mothers were using modern contraceptive for family planning.

Knowledge on immunization services and vaccine preventable diseases (VPDs)

Most of the respondents (52%) had heard of immunization while 48% had not. Mothers/caregivers knowledge of immunization and vaccine preventable diseases had significant relation with fully immunized children in the study. Those mothers/caregiver’s with good knowledge on immunization and vaccine preventable diseases were more likely to be fully immunized as compared to those with poor knowledge on immunization and vaccine preventable diseases. A similar study was carried out by Mesfin which showed that mothers/caregiver’s with children aged 12-23 months had good knowledge of immunization and vaccine preventable are 6.18 times likely to be fully immunized compared to those with poor knowledge on immunization and vaccine preventable diseases. A study by Barhane also revealed there was relationship between fully immunized children with good knowledge on immunization compared to those mothers/caregivers with poor knowledge on immunization. Two thirds of KII respondents cited the following reasons for incomplete immunization; distance to the facility, stock-outs of vaccines, drought, migration of nomadic pastoralist, staff attitudes, ignorance by community members and long waiting hours during immunization services.

In summary, the immunization coverage for the fully immunized child in the sub county was very low 47%, compared to national 77%. So far, mothers’ low educational status, long distance to immunization site, poor mothers’ knowledge about immunization, living in large family size, not attending ANC, and non-health facility delivery were hindering the achievement of full immunization coverage in the sub county. Based on the findings there was strong association of illiteracy with non-immunization of children in the sub county. Also, the study showed low utilization and access of immunization services by communities to the health facilities. Based on the research findings the chances of the county getting vaccine preventable diseases are very high because of low immunization coverage in the region coverage. Finally, public responsiveness on the importance of immunization in prevention of vaccine preventable morbidity and mortality was crucial.

None.

The authors declare there are no conflicts of interest.

None.

©2020 Langat, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.