Journal of

eISSN: 2373-4426

Case Report Volume 9 Issue 4

1Department of Pediatric Surgery, Royal Hospital, Oman

2MCh( Ped Surgery) FACS, Royal Hospital Muscat, Oman

Correspondence: Madhavan P Nayar MS, MCh( Ped Surgery) FACS, Royal Hospital Muscat, Oman

Received: June 28, 2019 | Published: July 4, 2019

Citation: Aseel HSMD, Madhavan PNMS. Complex cystic abdominal mass in an adolescent girl. J Pediatr Neonatal Care. 2019;9(4):92-95. DOI: 10.15406/jpnc.2019.09.00385

Ovarian tumors are rare in children with a reported incidence of 2.6 cases per 100000 population per year1 Cystic masses in abdomen are commonly seen in children and the differential diagnosis include ovarian cysts, cystic mesenchymal hamartoma of liver, duplication cysts of the alimentary tract, omental cysts, retroperitoneal cystic teratoma and large lymphangiomatous lesions. In addition there are many organ specific cysts seen with a lesser frequency. When the cysts are too large to be assessed by an US scan- first imaging modality currently used–diagnostic errors are common. If the child has presented with respiratory embarrassment, leading to orthopnea, a diagnostic or therapeutic paracentesis may be required, if there is doubt as to the organ of origin, especially in the absence of facility for an urgent MRI scan. Once the diagnosis is confirmed as an ovarian cyst, all attempts are made to perform a fertility preserving surgery; the recommended surgery is a Unilateral Salpingo Oophorectomy in cases of a Borderline Tumor of the Ovary.2 The following case report exemplifies the difficulties in initial assessment and management.

BA, a 12 years old girl was admitted through the ER, for inability to lie flat on the bed for approximately two weeks associated with some reduction in appetite in the preceding month. She had no bowel or urinary symptoms; and her LMP was on the day of presentation; with menarche 11months earlier. She denied any history of jaundice or bleeding disorder in the past. She weighed 39.7 KG, which was in the 3rd centile for her age. On examination she was not anemic and had no significant peripheral lymphadenopathy. Her abdomen was massively distended and one could not discern any organomegaly. The abdomen appeared fluid filled and was dull on percussion with minimal dilated veins on the abdominal wall. Investigations showed normal white cell count and ESR. The Serum AFP, Beta HCG, LDH and Liver function tests and renal function tests were normal. As the mass was not highly suspected to be ovarian in origin, a Ca 125 level or CEA level were not done at this stage. Next an US scan was done. This showed a giant fluid filled mass filling almost the entire abdomen, measuring over 38cms in the longitudinal axis and over 24cms in the transverse axis. The “cyst” was extending from pelvis to xiphi-sternum, compressing bowel loops and liver, moreover, appeared to show either loculation or septa. A clear “cyst” was not identified and the fluid filled mass was inseparably juxtaposed against the lower abdominal wall. The urinary bladder was seen partially filled. As an MRI scan was not immediately available, a CT scan with contrast was done (Figure 1 & 2).

Figure 1 CT scan image AP view showing the giant “cyst” with no clear walls and incomplete septation.

This showed a giant fluid filled mass, non-enhancing and without any calcification. The mass had faint septa; but did not show multi-loculation. The mass was compressing the liver and the diaphragm upwards and the bowel loops to the left upper quadrant of the abdomen. One could discern a normal ovary on the left side; but none on the right side. The radiologist felt that a fluid filled mass of lymphangiomatous origin was the first of the possibilities; with ovarian pathology as the next. This was in view of multiple septa seen on US scan, and normal biochemistry and normal tumor markers. As the fluid filled mass was causing orthopnea, it was decided to do a percutaneously drainage using a small tube, at the part where the mass was closely adherent to the abdominal wall, in the low right iliac fossa, using a 6F pigtail catheter. The procedure was uneventful and over the next 3 days, about 7800ml fluid drained. The fluid was almost colorless and cytological examination of the fluid done showed NO malignant cells or atypical cells. The weight of the patient reduced by 8.6KG, with complete relief of orthopnea. She was able to have full normal diet and normal bowel actions. An ultrasound scan was repeated and this confirmed that there was no free fluid in the peritoneal cavity. The cyst was still very large, and the computed residual fluid volume in the mass was 664 ml.

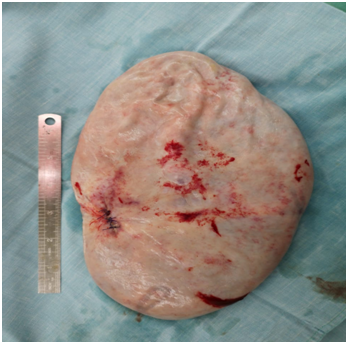

An MRI scan was done at this stage, in another hospital and this was reported as a probable right ovarian cyst with no solid component, no free fluid in the abdomen and all left fallopian tube, ovary and all other organs within normal limits. At this stage the patient was taken for laparotomy. A giant ovarian cyst was seen, attached to the abdominal wall, at the site of the pigtail drain. This part was isolated from abdominal cavity with multiple abdominal packs first. Next a double layer of purse string sutures were placed around the tube to avoid any fluid spill into the wound or abdominal cavity. A right salpingo-oophorectomy was done, after confirming that the opposite side ovary and tube were completely normal (Figure 3 ).

Figure 3 Removed specimen of the right ovary and tube. Suture line indicates the area of controlled drainage.

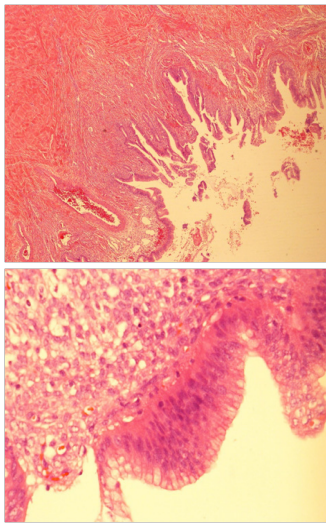

The liver, omentum and retro peritoneum were all normal. A thorough peritoneal lavage was done before closure, taking care to send the lavage returns for cytology- that was later reported as normal, with no malignant cells. Patient made an uneventful recovery and was discharged on the 3rd day. We received the final histology as follows. The cyst shows features of a Mucinous Cyst adenoma with Borderline Malignancy. No evidence invasion of the wall and no tumor of the external surface. Tubes showed evidence of salpingitis isthmica nodosa. FIGO classification Stage 1A (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Histology low and high power field showing papillaroid mucosa lined by mucinous lining epithelium which show stratification and atypia.

During case discussion in Tumor Board, it was felt that the patient be offered revision surgery for complete staging, as in adults, as the first surgery could be labelled as inadequate staging. Parents of the patient refused and opted to remain under close follow up. She is currently on six monthly follow up with Oncology and Pediatric Surgery and is doing well. She was seen on 21/1/2019, physical examination and pelvic US scan were normal.

Ovarian neoplasms are rare in pediatric population forming only 2.6/100000 cases per year1 In a series of 1037 malignant tumors published from Texas,2 the age adjusted incidence of ovarian malignancy was only 0.102 and 1.072 in children 0-9years and 10-19years per 100000 per year, respectively. Thus, ovarian malignancy is rare in children and adolescence, but they are the commonest genital tumors accounting for almost 60-70% of gynecological malignancies in this age group3 Ovarian tumors comprise of both benign and malignant varieties, both solid and cystic types. Germ Cell Tumors, surface epithelial stromal tumors and miscellaneous tumors like lymphoma, leukemia and small cell carcinoma. WHO has published a classification of ovarian tumors4 as Surface Epithelial Stromal tumors, Sex cord Stromal tumors, Germ Cell Tumors and Non Specified Malignant tumors.

The surface epithelial stromal tumors have been further sub classified as serous tumors, Mucinous Tumors, Endometrioid tumors, Clear Cell tumors, Transitional Cell tumors and Epithelial Stromal tumors. Any of this could be Benign, Borderline or Malignant. Abdominal pain is the commonest symptom, followed by abdominal mass. Other features include abdominal distension, nausea/vomiting, pseudo precocity or hirsutism, and vaginal bleeding. A number of tumor markers have been used in the management; both for initial work up and for monitoring post- operative progress and recurrence, if any. These include Alpha protein levels in serum, Beta HCG levels. Lactate dehydrogenase, CA 125 levels, Carcino-Embryonic Antigen levels and Inhibin and Mullerian Inhibiting substance levels. CA 125 levels are elevated in 50% of Borderline Epithelial stromal tumors.5 In this series with 25years of experience at Baylor Children Hospital, Texas, almost 2/3rd of the cases were of the mucinous type and the rest of the serous type. An interesting feature was that most of the mucinous variety was of FIGO Stage 1A, as in our cases. The median age for Borderline Ovarian tumors is 15.5 years of age. Giant ovarian epithelial tumors are rarely seen these days, due to early detection by various imaging modalities. While benign cystadenoma is the second commonest benign cyst in the adolescent, giant cystadenoma is rare in this age group. Giant Cystadenoma is commonly seen in the 4th or 5th decade.6 Large size of the tumor throws a diagnostic challenge, with cases diagnosed as Massive Ascites,7 before a final diagnosis is reached. The massive abdominal distention causing orthopnea and the lack of sonological or biochemical evidence of ovarian origin of the fluid filled mass, caused the radiologist to opt for a controlled paracentesis, as the initial treatment.

In general, tapping of an ovarian cyst is not recommended for fear of rupture, fluid leak into the peritoneal cavity, dissemination of malignant cells and upstaging of a tumor. This could result in chemical peritonitis, gliomatosis peritoni, and pseudomyxoma peritoni.8,9 Open surgery or laparoscopic surgery techniques have been modified to take care of these concerns. Though most of the laparoscopic techniques use an endobag for removal of the cyst, initial decompression with a trocar, in cases of giant cysts can prove difficult. In such instances, a small incision to reach the peritoneal cavity and perform a controlled drainage of the cyst is done first. Even in open surgery, as in our case, only a small incision is made first to seal the rest of the peritoneal cavity, and control the site of the aspiration. Recently tissue glue and transparent adherent sheets have been used on the cyst, prior to aspiration of the cyst, to minimize the risks of fluid leak.10 Fertility preservation is the goal of treatment in adolescent age group; and thus the recommendation is for oophorectomy or unilateral salpingo-oopherectomy.11 A more extensive surgery is considered as a second look option after full histology and if the tumor has spread beyond ovary. Borderline tumors of stage 1A and B are only followed up; Stage 1C and Stage 2 are offered either observation alone or managed as Low grade Epithelial Carcinoma, with IV Taxane/ Carboplatin-3-6 cycles. In our patient the fluid cytology, as well as the peritoneal washouts were negative for any malignant cells and there was no evidence of any malignant cell on the surface of the mass making it a FIGO Stage 1A.

A 12 year old girl presented with massive abdominal distention causing orthopnea. Despite ultrasonography and CT scan examination, diagnostic difficulties of its organ of origin and the need to give symptomatic relief, necessitated controlled paracentesis of the fluid filled mass. A borderline ovarian tumor of 8.6 KG weight was removed intact, by a fertility preserving right salpingo-oophorectomy, sparing the opposite normal ovary and tube and uterus. Final histology confirmed a Stage 1A Borderline Ovarian Tumor of the Mucinous Cystadenoma type. The case is reported for its rarity in this age group and is the first one reported in this country.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Director General of Royal Hospital for permission to publish patient related data for academic purposes. We would like to acknowledge and thank Dr Fatima Ramadhan Al Lawatia, Senior Consultant, Department of Pathology for the slides and the legend for the slides. Dr Thuria Al Rawahi, Senior Consultant, Department of Gynecology gave us suggestions regarding oncological aspects of the case and her help is gratefully acknowledged. Dr Mohammed Jaffer Sajwani as head of department of Pediatric surgery gave us help and encouragement for publishing this report. No grants or financial assistance was received in publishing this case report.

The authors declared there is no conflict of interest.

©2019 Aseel, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

International Childhood Cancer Day is observed on 15 February 2026 to raise awareness about childhood cancers and to highlight the medical, developmental, and supportive care needs of affected children and their families. This day emphasizes the importance of early diagnosis, pediatric care, and continued research to improve survival and quality of life in children with cancer.

Researchers and healthcare professionals are encouraged to submit their original research articles, reviews, and clinical studies related to pediatric oncology, neonatal care, and child health. Manuscripts submitted on the occasion of International Childhood Cancer Day will be eligible for a special publication discount of 30–40% in the Journal of Pediatrics & Neonatal Care (JPNC).

.

International Childhood Cancer Day is observed on 15 February 2026 to raise awareness about childhood cancers and to highlight the medical, developmental, and supportive care needs of affected children and their families. This day emphasizes the importance of early diagnosis, pediatric care, and continued research to improve survival and quality of life in children with cancer.

Researchers and healthcare professionals are encouraged to submit their original research articles, reviews, and clinical studies related to pediatric oncology, neonatal care, and child health. Manuscripts submitted on the occasion of International Childhood Cancer Day will be eligible for a special publication discount of 30–40% in the Journal of Pediatrics & Neonatal Care (JPNC).

.